- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Finansowanie społecznościowe projektów uniwersyteckich na przykładzie gouep.pl

Dobrosława Mruk-Tomczak1, Ewa Jerzyk2

1Department of Product Marketing, Poznań University of Economics and Business

Al. Niepodległości 10, 61-875 Poznań, Poland

2Department of Marketing Strategies, Poznań University of Economics and Business

Al. Niepodległości 10, 61-875 Poznań, Poland

*E-mail: *dobroslawa.mruk-tomczak@ue.poznan.pl

Dobrosława Mruk-Tomczak; ORCID: 0000-0002-4548-8260

E-mail: ewa.jerzyk@ue.poznan.pl

Ewa Jerzyk; ORCID: 0000-0001-8474-3570

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0008

Abstrakt:

Rozwój crowdfundingu poszerzył arsenał możliwych sposobów finansowania projektów naukowych oraz pozanaukowych, a także spowodował wzrost zainteresowania tych podmiotów, które do tej pory nie korzystały z tej formy kreatywnego finansowania. Amerykańskie uczelnie są zarówno pionierami w tej dziedzinie, jak też odnoszą największe sukcesy w pozyskiwaniu środków finansowych poprzez takie zbiórki. W Polsce crowdfunding na uczelniach wyższych jest na etapie wstępnego rozwoju, dlatego celem artykułu jest przedstawienie i ocena pierwszej platformy do pozyskiwania wsparcia społecznościowego na Uniwersytecie Ekonomicznym w Poznaniu — GOuep.pl. Doświadczenia i wnioski z pierwszych zbiórek na wybrane projekty dostarczają ciekawych, praktycznych implikacji dla potencjalnych zainteresowanych tym sposobem finansowania projektów. Zbiórki uniwersyteckie raczej nie wykraczają poza granice społeczności danego uniwersytetu, co czyni je lokalnymi, niewielkich rozmiarów projektami, o niezbyt wygórowanych celach finansowych. Finansowanie społecznościowe w przypadku uczelni krajowych jest jeszcze na tyle nowe i nieznane, że potrzeba sporo nakładów, zarówno finansowych, jak i wiedzy eksperckiej, aby móc w pełni z niego korzystać. To także edukacja całej społeczności akademickiej w kierunku wykorzystania potencjału zaangażowania się w uczelniane projekty, jako wydarzenia integrujące poszczególne grupy i wpływające na rozwój potencjału uczelni i jej atrakcyjności. Artykuł wnosi wkład w rozpoznanie predyktorów sukcesu finansowania społecznościowego na uczelniach wyższych w Polsce oraz wskazuje na możliwość wykorzystanie platform crowdfundingowych jako narzędzia budowania wizerunku szkoły wyższej i umacniania integracji wspólnot akademickich.

MINIB, 2023, Vol. 48, Issue 2

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0008

Str. 17-40

Opublikowano 31 czerwca 2023

Finansowanie społecznościowe projektów uniwersyteckich na przykładzie gouep.pl

Introduction

Public universities are facing financial difficulties, in particular, the drop in funding scientific research and development works is alarming. In the face of lacking funds and the funding application procedure being sometimes cumbersome, university employees search for alternative funding sources. This paper constitutes a presentation of the theoretical and practical use of crowdfunding platforms as an alternative source of crowdfunding in higher education that integrates the academic community around common goals. This funding model known for over 30 years is used also to support the universities’ activity in conducting various types of research, spreading knowledge, engaging in sports and hobby-related or generally understood entrepreneurial activity. At Polish universities crowdfunding is not widespread, even though it could, beyond the traditional funding system, ensure support for many necessary initiatives, build a community and strengthen the positive image of educational institutions.

Using the available academic literature and the case study method, we assessed factors determining the success in crowdfunding, while indicating issues and limitations resulting from the context of a non-profit institution that significantly determines the project specifics and success. Based on the case of GOuep.pl crowdfunding platform, we presented the essence, scope of activity and the fundraisings organised, and discussed the factors affecting the success or failure of projects. The experience in implementing the crowdfunding platform project at Poznań University of Economics and Business should foster crowdfunding awareness, which constitutes an innovative method to fund university undertakings.

The Essence of Crowdfunding

Crowdfunding is a neologism which was built from two English words 'crowd’ and 'funding’. In simpler terms it may be described as 'financing by a crowd’. It is the essence of crowdfunding, where 'the crowd’, that is Internet users, provides financial support for a variety of projects posted on crowdfunding platforms. The unique feature of the community of Internet donors is that it is compiled of individuals and organisations that relate to the project, have convergent goals and ideologies, and show similar enthusiasm towards the project. 'The crowd’ does not necessarily live in the same geographic area, neither is it connected by a preference for Internet platforms (Hassna, 2022). The term 'crowdfunding’ spread in Poland and is used on a day-to-day basis. Apart from 'the crowdfunding’ notion, another term used in Poland alternatively to express the essence of this form of providing financial support is 'financing by community’.

The beginning of crowdfunding was in the 1990s. At that time the 'Marillion’ music band asked its fans for financial support for a planned concert tour. According to researchers examining the matter, this was the first case of crowdfunding. Several years after this event, the first crowdfunding platform was launched in the United States, namely www.artisshare.net, dedicated to the artistic field. Nevertheless, 2008, when indiegogo.com and kickstarter.com platforms were launched, is viewed as the beginning of the dynamic growth of this financing method (Godziszewski, 2019). Till date, both platforms are recognised as the world’s largest crowdfunding platforms.

By the end of 2022, no unique, official definition of crowdfunding had been adopted. The first attempts of defining this phenomenon appeared in the beginning of the 21st century. At that time, Howe (2006) defined the term 'crowdsourcing’ and proposed CrowdFunding as one of its types. Other authors indicate that the first to introduce this term was Sullivan, who wrote in 2006 that '… funding from the crowd is the base of which all else depends on and is built on. So, crowd-funding is an accurate term to help me explain the core…’ (Dziuba, 2015, p. 9) In the subsequent years, the authors focused on defining this phenomenon while emphasising various aspects of its functioning (Malinowski & Giełzak, 2015, p. 24-25). In Poland, the first attempts to define crowdfunding were made by Król and Dziuba. The first of them, in 2013 came up with a definition indicating that, crowdfunding is a 'method of raising and allocating a capital donated for developing a given undertaking in return for a particular benefit that engages a wide group of capital donors, is characterized by the use of teleinformatic technologies, lower entry barrier and better transactional conditions than the methods available in the market’ (Pieniążek, 2014, p. 5). Two years later, Dziuba showed two approaches for crowdfunding. In the broader approach, he defined crowdfunding as 'any form of raising financial resources through a computer network (Internet), or with the use of social media.’ In the narrower approach, he emphasised the meaning of 'the process where, e.g. businessmen, artists or non-profit organizations raise funds for projects, undertakings, or organizations, based on the support of many people (of the Internet 'crowd’) who collectively donate money for such projects, undertakings, etc. or invest in them’ (Dziuba, 2015, p. 11).

Looking from a wider perspective, one may identify certain phenomena and processes that constitute a basis for the development of crowdfunding (Brunello, 2016, p. 30):

- It operates at the intersection of new economic forms and social networks;

- It is developing thanks to the formation of new economic communities based on horizontal funding; It activates society to achieve common goals;

- It uses technological achievements and strategies enabling individuals or groups to obtain the financial resources needed to implement their projects.

Taking into consideration various opinions on approaching crowdfunding definition, one may indicate certain features that remain constant and stable, which makes them the most important determinants in defining crowdfunding (Król 2013; Malinowski & Giełzak, 2015):

- The fundraising is organised on the Internet, through a crowdfunding platform;

- The project beneficiary is described in detail;

- The goal and the amount of fundraising are precisely determined;

- The fundraising has a closed-project character with a specified starting and ending date;

- The support provided by donors is always financial;

- The fundraising has an open nature, that is, the payment may be made by anyone from any location and in any amount;

- The funders may (but do not have to) receive various kinds of prizes in return for their support.

As the presented funding model for various projects developed, Dziuba (2015, p. 22-23) recommended a typology where he distinguished four basic crowdfunding models and sub-models. The first, and the most popular model is the donation model, the core of which is raising funds for a determined goal, including charity goals. This model may assume donors are not being awarded (charity model) or being awarded a form of nonfinancial reward (known as the sponsor model or the model based on additional services). The platforms operating in the donation model are the most common in Poland (Pluszyńska & Szopa, 2018, p. 41). The second is a lending model (also called debt crowdfunding), which consists in offering loans while omitting traditional financial institutions. They usually

constitute direct social lending or microloans. The next, third model, also called the investment-type model, offers space for investors to allocate their free financial resources to certain undertakings, and expect a return on this investment, among others, in the form of a share in future income from the sales of goods, services or share in profits. In this model, the author distinguished numerous sub-models, depending on the form of gratification expected by the donor. The last, fourth basic crowdfunding model, called the hybrid model, merges the models listed above into one model, taking into consideration all previously mentioned models or selected ones, both in the form of horizontal integration (merging among models) or vertical integration (merging among sub-models).

Within donation crowdfunding, which constitutes the subject matter of this paper, there is a significant distinction to be made that refers to the operation of the platform rather than the adopted model, and takes into account whether the raised amount is obtained or not. There are two solutions available. Some platforms use the solution 'all-or-nothing’, which means that the beneficiary obtains the raised funds only if the total of all donations reaches the financial goal assumed for the project. In this case, if the financial goal is not reached within a predetermined time limit, the payments are returned to funders’ accounts. In the second solution 'keep-itall’ when the project is finished, the project initiator receives the raised amount, regardless of whether the financial goal was achieved or not (Brunello, 2016, p. 42).

Crowdfunding in Poland

Crowdfunding is one of the most dynamically developing alternative funding forms, also in Poland, where 2021 turned out to be a recordbreaking year for crowdfunding (Bandura, n.d.). The Poles organise and finance a variety of fundraisings published on crowdfunding platforms, such as charity, business, science, social issues-related and individual ones, in order to pursue a hobby or passion (Crowdfunding w Polsce na fali, 2021). It is difficult to find the exact statistics indicating the number of crowdfunding platforms operating in Poland. However, according to experts, several dozens of such platforms, including all the types described above, operate in the country. The greatest diversity of projects may be found on platforms of general purpose (including zrzutka.pl; wspieram.to), where projects in various fields are posted (including those related to travels, animals, sports, culture, but also charitable fundraisings). Others are typically charitable platforms (among others Siepomaga.pl) with projects related to supporting individuals in need (e.g. fight against disease, rehabilitation), charity organisations or helping animals. Equity (e.g. beesfund.com) or crowd-investment (e.g. crowdway.pl) platforms represent another category of platforms enabling interested individuals to invest in various projects, often in return for shares in a given undertaking. In the years 2014–2017, the average monthly amount contributed by Poles to crowdfunding equalled 278,000 zlotys, and in 2021 it was 60 times higher (Szymański, 2022).

The value of the entire crowdfunding sector, excluding the social lending sector, was nearly 1.4 billion zlotys. Donation crowdfunding constituted the largest part of the Polish market (e.g. nearly 250 million PLN were raised on the zrzutka.pl platform only in 2021). 2022 was equally successful. Crowdfunding was worth 1.1 billion zlotys, and Zrzutka.pl — the leader in the sector achieved a record value of financial resources raised with online fundraisings during 1 year, with dynamics of over 27%. The highest percentage-based growth in the recent years occurred in equity crowdfunding, which skyrocketed by over 4,900% in Poland in the years 2016-2021. However, since early 2022 the platforms that were previously leading in development dynamics in the field, have been facing a harder period (Duszczyk, 2023). The crowdlending sector, which is the sector of social lending, has been developing equally dynamically. Its value at the end of 2021 exceeded 2 billion zlotys (Bandura, n.d.). The maturity of the crowdfunding market in Poland is reflected by the fact that platforms dedicated to specific sectors of this market emerge. For example, in January 2021 a crowdfunding platform operating in a reward crowdfunding model (https://zagramw.to/) was launched for the purpose of fundraisings for board games. Nearly 5 million dollars were raised through this platform (Crowdfunding w Polsce na fali, 2021). The latest expert forecasts indicate, however, that in 2023 the value of crowdfunding will shrink by 10%, to the level of 1 billion zlotys or below that value. Such a trend is explained by a further economic downturn, high inflation and the related impoverishment of society (Duszczyk, 2023).

Crowdfunding in Higher Education

Crowdfunding is more and more often employed to obtain additional funds by universities around the world, in particular in the United States. Typically, the researchers and students are the beneficiaries of these projects (Horta, Meoli, & Vismara, 2022). This financing method may increase the resources available for science or partially compensate for the insufficient budgets of financing units (Sauermann, Franzoni & Shafi, 2019). Embracing crowdfunding in the higher education sector was a natural consequence of the new policy that tried to transform universities and make them more market-oriented, that is, acquire certain corporate features. The more so, since in order to cover the increasing costs, universities had to start seeking contributions to their budgets from other sources. Crowdfunding platforms became present at many American universities (Crowdfunding for Universitiesñ, 2015). They range from the most prestigious ones, with the activity concentrated mostly on conducting scientific research and using the additional support mostly in this area, to the less distinguished, teaching-oriented ones, searching for additional funds for improving educational and didactic materials (Horta et al., 2022). European universities do not have such traditions of raising funds. As opposed to their American counterparts, most public European universities (except for those in the United Kingdom) still rely on state support to the highest extent. European cases show that the activities related to raising financial resources are implemented in short-term projects of ad-hoc nature and student participation in them is far from the American model (Nastase, 2018). With respect to incorporating crowdfunding into the university strategy, some of them choose to build their own platform using the available internal resources. Others, by contrast, seek cooperation with external experts that provide ready-made solutions, in the form of both technology and specialist support. It should, however, be emphasised that there is no unique approach in the scope of incorporating crowdfunding into the fundraising strategy that might be applied to all universities (Alma’amun et al., 2021). It is worth underlining that crowdfunding combines fundraising with public engagement and the spirit of entrepreneurship (O’Donnell, 2022), which in the case of universities constitutes additional value.

Crowdfunding platforms operating in higher education are largely based on the donation model, where the funders voluntarily support a selected project and do not expect any rewards or other services in return (Horta et al., 2022). For a university, crowd-based financing may constitute a method not only for obtaining financial resources but also for having the proposed ideas verified by virtual communities. A large number of projects implemented with the use of such platforms, mostly in the USA, may show increasing interest in the will to obtain additional support. The projects are mostly related to funding teaching, scholarships, scientific projects, research or travels of students and researchers. The crowdfunding platforms initiated by American universities are most frequently related to (Lenart-Gansiniec, 2020):

- Funding scientific research carried out by the employees and students;

- Funding sports teams;

- Funding scholarships;

- Funding student travels.

Equally significant is the fact that crowdfunding platforms create a new type of space for marketing communication with all of the university stakeholders (Stasik &Wilczyńska, 2018). They may serve for presenting many diverse activities undertaken by both the scientists and students to a wider public, thus integrating the whole academic community around common goals. It was pointed out that if the possibility to support the projects posted on crowdfunding platforms was not communicated properly to the groups of potential donors, the beneficiaries lost numerous opportunities to obtain support (Jung & Lee, 2019). Apart from being a communication instrument, a crowdfunding platform may become a modern tool for promoting the image of a university and its activity, not only scientific but also social.

The cases of American platforms operating by universities have also shown that relations constituted the most important element determining the will to provide financial support. The sense of belonging and bonding among the university stakeholders are the key factors in successful fundraisings, and sustained care for these relations results in long-lasting success (Jung & Lee, 2019).

Many universities in Europe, and above all in the United States, have their own crowdfunding platforms. Examples from all over the world show that crowdfunding platforms operating within universities and higher education schools are successful in implementing many diverse projects. In Poland, until 2019, when the GOuep.pl platform was launched, none of the public universities have undertaken such activity.

GOuep.pl Crowdfunding Platform

Launching a crowdfunding platform at Poznan University of Economics and Business (PUEB) originated in attempting to address the issue of limited financial capability of the university and other institutions that finance the activities and research conducted by both the PUEB employees and students. Apart from that, the decision to launch the platform was made having contemplated the role and significance of crowdfunding platforms in obtaining support at multiple universities in the United States. Fundacja UEP (the PUEB Foundation) was the initiator of this undertaking. The management board and the employees of the Foundation, having used the desk research method to examine the entities operating in the crowdfunding field both in Poland and worldwide, and having scrutinised the needs of the academic community, in particular the students and employees, recommended launching the GOuep.pl crowdfunding platform, in the donation model, and the 'all-or-nothing’ system to PUEB authorities. The selection of this model was an effect of market analysis, which proved that the donation model of crowdfunding was most frequently used by higher education institutions and academic communities (Tutko, 2018), which constituted the source of inspiration for the initiators of the platform. The analysis of sample crowdfunding platforms run by American universities shows that they provide significant support in obtaining funds for the implementation of numerous scientific and extracurricular projects while being platforms that integrate the academic community.

After a month-long period of planning, and developing a concept plan and technical infrastructure, in May 2019 the Rector of PUEB officially announced that GOuep.pl crowdfunding platform was being launched.

PUEB Foundation as an initiator and executive coordinator of the platform became its administrating body. Terms and Conditions were prepared to determine detailed rules and conditions of platform use and operation, including the rights and obligations of its users and the Foundation as its administrating body. Any natural or legal person, or an organisational unit without legal personality that uses the platform, in particular as a beneficiary or a donor, may be a user of the GOuep.pl platform.

The beneficiaries of GOuep.pl include in particular students of all study modes and degrees, entered onto the list of PUEB students, student research societies (SRSes) registered at PUEB, scientific employees, scientific and didactic employees, and didactic employees employed by PUEB, PUEB units separated according to PUEB organisational structure and operating at PUEB [e.g. Klub Partnera (Partner Club), Stowarzyszenie Absolwentów (Association of Graduates)]. The Foundation, as the administrating body, has a beneficiary status as well, and as such is entitled to charge a part of the donated amounts for maintaining the service and covering its own statutory goals, but also submitting its projects and organising fundraisings for their implementation. Whereas any natural person who has a full legal capacity, a legal person or organisational unit without legal personality may be a donor.

The fundraisings implemented through the GOuep.pl platform may be related to:

- Science (e.g. conducting research, commercialising results, participating in scientific conferences, purchasing equipment, research-related travelling);

- Self-development (e.g. participating in paid conferences or training);

- Improving the quality of common space used by the PUEB academic community (e.g. projects related to spatial development);

- A hobby (e.g. a study visit, organising an exhibition);

- Acting for the benefit of the academic community (e.g. organising a concert, meeting, or seminar).

Integrating the academic community around interesting undertakings proposed by individuals, teams or units related to PUEB is an important goal in the platform’s operation. The possibility of financially supporting individual business goals, charity goals or goals related to medical treatment, social support or social help was excluded.

Users, in particular the beneficiaries, use the platform via their user accounts. Donors are not obliged to create an account; however, if they chose not to, they may use the platform in a limited scope and their donations to the selected projects remain anonymous. The registration of a potential user and creating an account is only possible after the uploaded registration form passes a verification with a positive result. Creating an account is free of charge; however, the users who are the beneficiaries are charged for the organisation of the fundraising and execution of the donation. Under the Terms and Conditions, the administrating body of GOuep.pl charges a fee for organising the fundraising and maintaining the website in the amount of 10% of the amount paid as a donation. The payment service provider charges 1% of the paid amount as a commission for assistance in electronic payments.

The attractiveness of the crowdfunding platform depends in the first place on the level of attractiveness of the projects posted on it. The attractiveness relates to both the benefits for a specific beneficiary and also, in a broader sense, to the entire academic community. The beneficiary uses an online form at GOuep.pl to submit a description of the planned fundraising with the administrating body. To support beneficiaries in preparing the project, the administrating body posted additional information at GOuep.pl in the 'How to submit a project’ tab. It contains detailed tips on how to prepare a project, how to describe and interestingly present it, and how to promote it internally (among the academic community) and externally among potential donors unrelated to the PUEB community. It must be emphasised that funders support rather the people behind the projects than the projects themselves. The credibility and trust in the project initiator are important factors contributing to the success of a given fundraising. Therefore, the description showing one’s passion, engagement and belief in the success of the project may affect its accomplishment. Attracting the interest of potential donors is equally important. The more widespread the interest, the greater the chance for the project to succeed (Biela, 2018). In this phase, the project initiator must obtain the opinion of another person (a student — of their thesis supervisor or a lecturer, SRS — of its advisor, PUEB employee — of another employee of the University, PUEB units — of the person that supervises them, units operating in connection with PUEB and PUEB Foundation — of the University employee adequate for the subject matter of the project). In the next phase, the representatives of the platform’s administrating body perform formal verification of the application and forward it to subjectmatter verification. The community grants a vote of confidence to selected projects and supports them with their payments; therefore an important task to be performed by the platform’s administrating body is to verify the submitted ideas so that the supporters do not get disappointed and lose trust in the platform. The subject-matter assessment is performed by the Management Board of PUEB Foundation in cooperation with experts in the field the project relates to (e.g. scientists and experts in practical economy), invited on each occasion. The verification and assessment of the project from the date of its submission until its acceptance are not longer than 3 weeks. After a preliminary acceptance of the project, its initiator is requested to prepare a detailed presentation of the project, including a clearly specified goal, period and the expected amount of support. Determining the period of fundraising is an important element of planning the crowdfunding project, and it may affect the success of the undertaking. The general opinion is that shorter campaigns have better chances of collecting the demanded amount. The statistics shared show a correlation between the initiative’s lasting period and its chance to be funded. From a statistical point of view, longer projects fail more often. The projects with smaller budgets have a greater chance to reach their goals and secure the success of the entire campaign (Sauermann et al., 2019). Apart from setting the period of fundraising, it is important to plan the dates when the campaign starts and ends, since they are the key moments in each crowdfunding campaign (Malinowski & Giełzak, 2015, p. 95).

After the final acceptance of the project description, amount of and period of fundraising, the administrating body posts the project on the platform in an adequate category, selected from the previously listed. At this moment the fundraising begins. In this phase, the key activities on the part of the project initiator are communication and promotion actions. An attractive way of presenting the project draws the attention of potential donors, allows it to stand out from other projects and may affect the final success of the fundraising (Awdziej, Tkaczyk, & Krzyżanowska, 2018). Therefore, the project’s success will depend on the beneficiary’s skills and knowledge on how to promote their projects, and how to reach a wider group of potential donors and interest them in the undertaking. A donor interested in supporting a given project financially pays a selected amount through the platform. The fundraising is continued for a period specified in the project description. After the lapse of this period, the administrating body, under the provisions of a separate agreement, transfers the monetary funds collected in the fundraising and decreased by the donation for PUEB Foundation and the commission on payments to the beneficiary, in accordance with a donation agreement concluded between the foundation and the fundraising beneficiary. The amount of a due gift tax is covered in full by a beneficiary. Under the terms and conditions of the platform, the amount received by the beneficiary must be spent in full on the implementation of the fundraising goal, which is confirmed by the beneficiary in a written report on spending the funds raised through the platform, sent to PUEB Foundation. A tab 'How to support a project’ dedicated to all potential donors of fundraisings on the platform was posted on the website by the administrating body. Information on how to support a given project, how to transfer a chosen amount and what happens to the transferred money may be found there.

Under the terms and conditions of the platform, the beneficiary obtains the collected amount if the financial goal is achieved. If the amount raised exceeds the goal before the final deadline specified in the project description, the raising is continued. The achieved surplus is transferred to the account of the 'Rozkręcamy koła’ (’Let’s rock the research societies’) Fund set up by PUEB Foundation. The money is allocated only to the goals related to supporting the scientific societies operating by PUEB. Similarly, if the fundraising period specified in the project description lapses and the assumed amount of support is not reached, the collected funds are transferred to the same Fund.

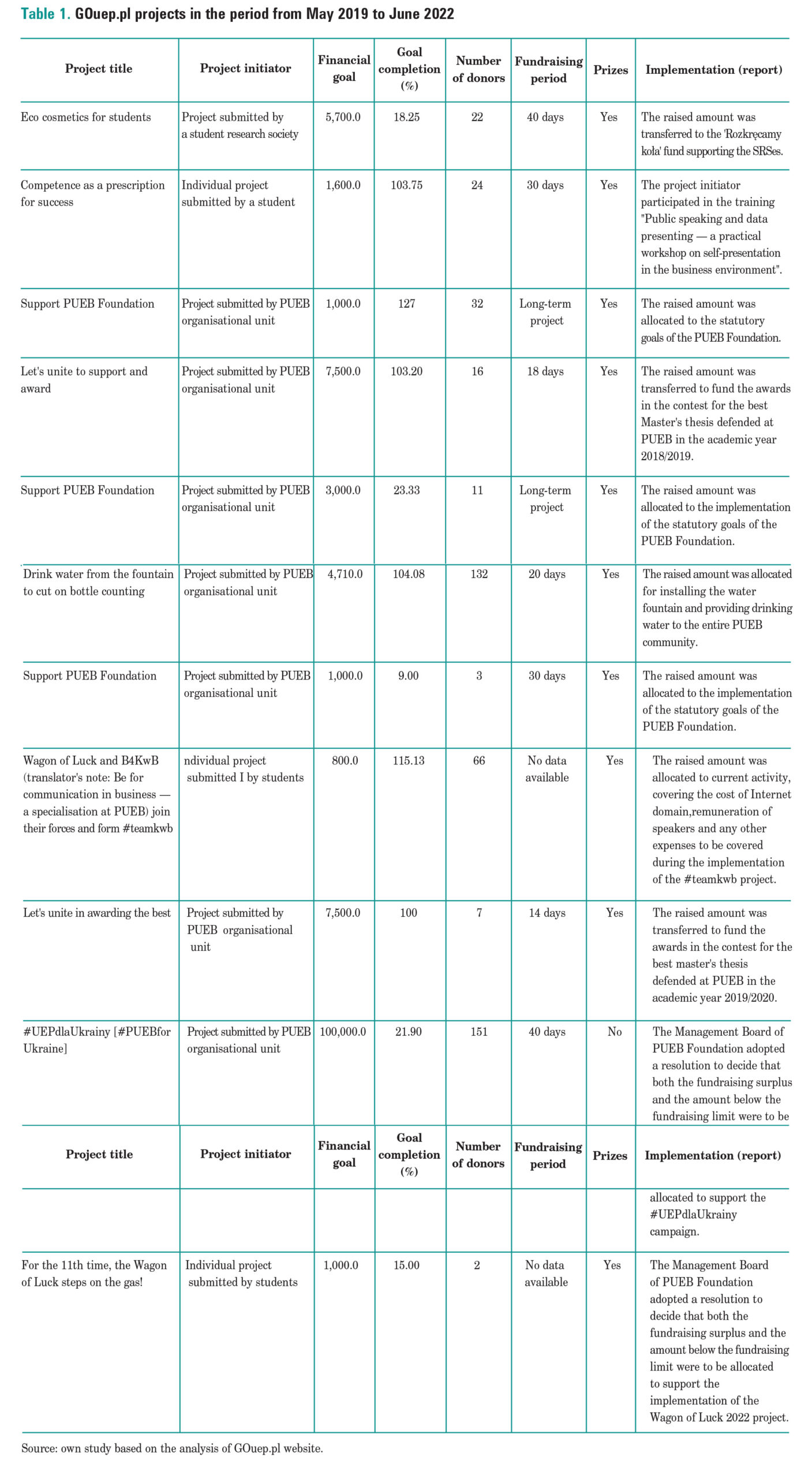

Since the GOuep.pl crowdfunding platform was launched, it has been used to organise 11 fundraisings in total, three of which were individual projects submitted by students, seven were submitted by UEP organisational units and one by a student research society. Six projects, with a total value of PLN 23,110, reached complete funding, which means that 100% of the assumed amount was raised. Thanks to online fundraising, the installation of the first drinking water fountain available to the entire university community was funded, among others. Another fundraising completed successfully was obtaining financial support for the prizes in the 26th contest for the best Master’s thesis defended at PUEB. Another project, submitted by an individual student, that obtained full support, was related to raising funds for participation in the dream public speaking training (Table 1).

PUEB, Poznan University of Economics and Business; SRSes, student research societies.

Ten out of 11 posted fundraisings were based on the reward system, ranging from minor, symbolic rewards (e.g. a thank-you card) to material rewards (e.g. glass water bottle with the PUEB logo). The type of reward was related to the donated amount. The larger the donation amount the higher the reward level. The higher-level rewards, in particular the material rewards, were usually limited, and the website of each project displayed the current information on how many rewards were still available. The proposals of rewards and their funding were always included in the scope of the project beneficiary. Therefore, it was important to consider the cost of rewards in the phase of planning and include it in the final cost estimate.

The types of projects posted to the GOuep platform were related to absolutely different fields than the projects implemented at American universities. No projects related to scientific research, support for sports teams, scholarships and university travels, which constitute the most common crowdfunding initiatives in the USA, appeared. The projects initiated by the PUEB organisational units were the most common and the second most frequent were students’ projects.

Conclusions

The beginnings of the PUEB crowdfunding initiative were based on the enthusiasm of the individuals engaged in the work of the Foundation. In retrospect, it seems useful to elaborate a specific model to support the fundraisings by establishing a fund to be used by project initiators to promote their fundraisings. Such a supporting programme would enable preparing a promotional campaign to promote the new GOuep.pl projects, that do not have adequate impetus, especially in their first, initial phase. However noble, the assumption that any financial resources from the unaccomplished projects or surplus would be transferred to the development of SRSes, was simultaneously limiting the chances of future fundraisings to succeed. Changing the GOuep.pl operating model is also worth considering. Instead of an 'all-or-nothing’ solution, a model where the beneficiary receives the entire collected amount regardless of whether the financial goal was reached or not could be proposed. The guarantee of receiving the collected amount could motivate the project initiator for greater engagement in promoting the fundraising; what is more, it could be a greater incentive for other project initiators to post more fundraisings.

Compared with for-profit organisations, university crowdfunding has better chances to obtain funding from the community (O’Donnell, 2022). It most certainly follows from the social understanding that science needs subsidising and that it is necessary to fight the bureaucracy in applying for funding scientific undertakings. The success of fundraisings on university crowdfunding platforms is related to donors’ trust in the institution, person or team responsible for the project, as well as simple and intuitive forms of support (payment system).

As outlined, encouraging a sense of belonging and bonding among the university stakeholders, not only currently within the university but including the graduates and business environment, is an important component of success in fundraising. Caring for, cultivating and fostering these relations brings effects in the form of long-term success in fundraising (Jung & Lee, 2019). Therefore, the success of the GOuep.pl platform may be related to the type and strength of the relationship the university develops with its stakeholders.

O’Donnell (2022) claims that students and employees with a PhD degree achieved greater success in crowdfunding than older scientists, and women had a higher success rate than men. Based on our observations, we were not able to make unambiguous conclusions on whether similar relations occurred in crowdfunding projects at GOuep.pl. What is more, the profiles of donors who identified themselves with projects have not been analysed, which should be done in future to understand the motivations of individuals making donations. Although crowdfunding is present in Poland, its awareness among students and employees of universities is not complete (Gemra & Hościłowicz, 2021). Consequently, the success of future university fundraisings depends on the growth of awareness among the academic community combined with publicising the success stories of subsequent fundraisings and appreciating the social dimension of supporting the projects. It is worth noting that such a platform is a valuable asset that might be used in the educational process to teach students entrepreneurial and creative approaches towards the implementation of their own goals. It is also a perfect instrument that fosters proactive attitudes, altruistic engagement with helping other students or university units to attain their goals and shaping the feeling of ability to influence the events happening at the university. It was shown that if students are efficiently engaged or participate in the development of their university, a basis for future engagement is formed and the intention to support their university as graduates arises (Jung & Lee, 2019). Therefore, encouraging and motivating students to engage in organised fundraisings may efficiently develop the sensitivity of future graduates towards the University of Economics and Business.

Each of the projects seeking crowdfunding at GOuep.pl had a clear vision and set financial goals. However, their promotional campaigns had low reach, the social media possibilities were not used in full, and the authors of the projects had different skills and competencies when it comes to Internet marketing. The studies (Eisenbeiss, Hartmann, & Hornuf, 2022) show that posts on social media are significant, both in the persuasive and informative forms, especially if they contain a reference to the success of previous campaigns and emphasise a large number of sponsors.

Bushong, Cleveland, and Cox (2018) write that raising funds by crowdfunding is a sprint and not a marathon, thus it would be recommended that in the future, individuals having broader experience in marketing, in particular in practical social media use, are engaged. Improving the success rate of crowdfunding campaigns using spectacular, engaging and emotional marketing actions will translate into a larger number of projects seeking financial resources with the use of crowdfunding. It seems reasonable that any promotional action should have a nature that integrates the academic community. Such value-related and emotional features constitute significant components of efficient crowdfunding on the one hand and develop the university’s image on the other.

O’Donnell’s (2022) studies indicate that strong leadership, and support of the most senior university authorities to advocate the platform, constitute an important aspect of the crowdfunding model. Mental support of the University Rector and Vice-Rectors should include administrative tasks such as developing promotional materials or assistance in opening an account for Internet payments Nevertheless, the mental support of university authorities may not mean taking over the responsibility for a project that rests on a person or team who seeks financial support.

The project posted on a crowdfunding platform may also motivate establishing relations with the business environment. In search of a new source of funding, the initiators may address their projects to selected individuals or institutions that operate in the field it relates to. As a consequence, the group of potential supporters interested in a given project will broaden, and an opportunity to establish a relationship with representatives of a given industry will open up, which may help the implementation of the project and affect further cooperation.

Although crowdfunding seems to be a relatively easy method to raise funds for projects, it still needs strong engagement, external support (the authorities, administration) and efficient campaigns that usually generate costs before first contributions are made. The specific character of university fundraisings must also be emphasised since they usually do not reach beyond a given university’s community, making them rather small, local projects with moderate financial goals. It is still not clear how to measure the success of the fundraising concerning the career and scientific achievements of the project author. Since the academic community appreciates the received subsidies in grant competitions, crowdfunding success should also be adequately measured in the reputation and esteem of a scientist, educationist, administrative employee, or student who stands behind the project.

The significance of our findings is practical, because they may be used by other universities searching for alternative methods to fund scientific and extracurricular undertakings that constitute a specific value for a given university community. Based on the case of the GOuep platform, it was shown that crowdfunding may constitute an alternative source of funding for various university projects. However, crowdfunding, successfully employed at American universities, is still so new and unexplored at universities in Poland, that significant resources, both financial and in the form of expert knowledge, need to be spent in order to take full advantage of it. It is also a lesson for the entire academic community on how to use the potential of engagement in university projects, understood as events that integrate individual groups and affect the development of the potential and attractiveness of a university.

References

1. Alma’amun, S., Khairy Kamarudin, M., Rozali, N. S., Nor, S. M., Sabarudin, N. A., & Rosli, F. A. (2021). From government funding to crowdfunding: Identifying approaches and models for universities. Revista Gestao Inovaçao e Tecnologias, 11, 4586–4609. doi:10.47059/revistageintec.v11i4.2486

2. Awdziej, M., Tkaczyk, J., & Krzyżanowska, M. (2018). Opis projektu crowdfundingowego a skłonność do jego wspierania przez darczyńców. Studia Oeconomica Posnaniensia, 6(5). 7–18. doi:10.18559/SOEP.2018.5.1

3. Bandura, J. (n.d.). Ile wart jest polski rynek crowdfundingu, a ile światowy? Retrieved from: https://crowdzone.pl/ile-wart jest-polski-rynek-crowdfundingu-a-ile-swiatowy. [Access date: 23.01.2021].

4. Biela, M. (2018). Teoretyczne założenia crowdfundingu oraz jego regulacje prawne w Unii Europejskiej i w Polsce. Rocznik Europeistyczny, 4, 97–105. doi:10.19195/2450-274X.4.8,

5. Brunello, A. (2016). Crowdfunding. Warszawa, Poland: CeDeWu sp. z o.o.

6. Bushong, S., Cleveland, S., & Cox, C. (2018). Crowdfunding for academic libraries: Indiana jones meets polka. The Journal of Academic Librarianship, 44(2), 313–318. doi:10.1016/j.acalib.2018.02.006

7. Crowdfunding for Universities. A special report by Crowdfunder. Crowdfunder.co.uk. 2015. Retrieved from: https://www.plymouth.ac.uk/uploads/production/document/ path/3/3911/CFUK_university_white_paper_V_085__3_.pdf. [Access date: 08.10.2022].

8. Crowdfunding w Polsce na fali, 2021. Ponad 2 mld złotych w 2021 roku. Retrieved from: https://www.wirtualnemedia.pl/artykul/crowdfunding-w-polsce-ponad-2-mld-zlotychw2021-roku-jak-zorganizowac-zbiorke-w-internecie. [Access date: 11.06.2022].

9. Duszczyk, M. (2023, February 27). Crowdfunding w Polsce czeka ciężki rok. Rzeczpospolita.

10. Dziuba, D. T. (2015). Ekonomika crowdfundingu. Zarys problematyki badawczej. Warszawa, Poland: Difin.

11. Eisenbeiss, M., Hartmann, S. A., & Hornuf, L. (2022). Social media marketing for equity crowdfunding: Which posts trigger investment decisions? (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 4076954). doi:10.2139/ssrn.4076954

12. Gemra, K., & Hościłowicz, P. (2021). Crowdfunding awareness in Poland. Gospodarka Narodowa. The Polish Journal of Economics, 306(2), 67–90. doi:10.33119/GN/134629

13. Godziszewski, B. (2019). Platformy crowdfundingowe w Polsce i na świecie — ile to kosztuje? Jakie prowizje? Retrieved from: www.mambiznes.pl.

14. Hassna, G. (2022). Crowdfund smart, not hard — Understanding the role of online funding communities in crowdfunding success. Journal of Business Venturing Insights, 18, e00353. doi:10.1016/j.jbvi.2022.e00353

15. Horta, H., Meoli, M., & Vismara, S. (2022). Crowdfunding in higher education: Evidence from the UK Universities. Higher Education, 83, 547–575. doi:10.1007/s10734-02100678-8

16. Howe, J. (2006). Crowdsourcing: A definition. Retrieved from: http://crowdsourcing. typepad.com/cs/2006/06/crowdsourcing_a.html. [Access date: 20.06.2022].

17. Jung, Y., & Lee, M. Y. (2019). Exploring departmental-level fundraising: Relationshipbased factors affecting giving intention in arts higher education. International Journal of Higher Education, 8(3). 235–246. doi:10.5430/ijhe.v8n3p235

18. Król, K. (2013). Crowdfunding. Od pomysłu do biznesu, dzięki społeczności. Warszawa, Poland: crowdfunding.pl

19. Lenart-Gansiniec, R. (2019). Zastosowanie crowdsourcingu w szkolnictwie wyższym. In Ł. Sułkowski, & J. Górniak (red.), Strategie i innowacje organizacyjne polskich uczelni. Kraków: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego. 223–235. e-ISBN (pdf): 978-83233-7011-6.

20. Malinowski, B. F., & Giełzak, M. (2015). Crowdfunding podręcznik. Gliwice, Poland: Helion.

21. Nastase, P. (2018). Hidden in plain sight: Student fund-raising in Romanian universities. International Review of Social Research, 8(1). 47–54. doi:10.2478/irsr-20180006.O’Donnell, J. (2022). Administration of crowdfunding at Australian universities. Business Horizons, 65(1), 33-42. doi:10.1016/j.bushor.2021.09.001

22. Pieniążek, J. (2014). Finansowanie społecznościowe a nowe trendy w zachowaniach konsumentów. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 12(2), 3–24.

23. Pluszyńska, A., & Szopa, A. (red.). (2018). Crowdfunding w Polsce. Kraków, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

24. Sauermann, H., Franzoni, C., & Shafi, K. (2019). Crowdfunding scientific research: Descriptive insights and correlates of funding success. PLoS ONE, 14(1): e0208384. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208384

25. Stasik, A., & Wilczyńska, E. (2018). How do we study crowdfunding? An overview of methods and introduction to new research agenda. Central European Management Journal, 26(1), 49–78. doi:10.7206/jmba.ce.2450-7814.219

26. Szymański, K. (2022) Crowdfunding, czyli finansowanie społecznościowe. Definicja, dostępne platformy i zastosowanie. Retrieved from: https://direct.money.pl/ artykuly/porady/jak-zdobyc-pieniadze-na-realizacje-marzen,190,0,2378430. [access date: 09.10.2022].

27. Tutko, M. (2018). Zastosowanie crowdfundingu w szkolnictwie wyższym. Zarzadzanie Publiczne, 2(42), 205–215. doi:10.4467/20843968ZP.18.016.8454

Dobrosława Mruk-Tomczak — Employed as an assistant professor at the Poznań University of Economics and Business. She conducts scientific and teaching activities, is a promoter of engineering and master’s theses. Area of interest: marketing communication, creativity, sustainability, brand management, consumer behaviour.

Ewa Jerzyk — Employed as a professor at the Poznań University of Economics and Business. She conducts scientific and teaching activities, is the promoter of master’s and doctoral theses. Research interests: buyer behaviour, marketing communication, design and packaging, neuromarketing.