- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Plan równości płci jako element budowania marki instytucji badawczej w kontekście employer branding

Sylwia Jarosławska-Sobór

Central Mining Institute-National Research Institute

Plac Gwarków 1, 40-166 Katowice, Poland

E-mail: sjaroslawska@gig.eu

ORCID: 0000-0003-0920-6518

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0004

Abstrakt:

Celem artykułu jest omówienie możliwości wykorzystania planów równości płci do budowania marki, szczególnie marki pracodawcy (Employer Branding) instytucji badawczej. Przedstawione to zostało na przykładzie Planu Równości Płci Głównego Instytutu Górnictwa – Państwowego Instytutu Badawczego. Metodologia badań obejmowała analizę danych zastanych oraz badanie ankietowe wszystkich pracowników GIG-PIB, nie tylko na stanowiskach badawczych i naukowych. Ankieta badawcza typu CAWI obejmowała pięć obszarów badawczych kluczowych dla zagadnienia równości płci, takich jak: równowaga między życiem prywatnym/rodzinnym a zawodowym (work-life balance), równowaga płci w kadrze zarządczej i gronach decyzyjnych, równość płci w procesie rekrutacji i rozwoju kariery, włączenie kwestii płci w procesie badawczym oraz środki przeciwdziałania przemocy ze względu na płeć. Niniejszy artykuł prezentuje wyniki zrealizowanego badania ankietowego. Analiza uzyskanych wyników pokazuje, że możliwości rozwoju zawodowego, naukowego i osobistego zostały ocenione pozytywnie przez kadrę pracowników GIG-PIB. Takie przychylne opinie pracowników są istotnym elementem budowania przewagi konkurencyjnej na bazie marki instytucji badawczej i jej Employer Branding.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 51, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0004

Str. 69-86

Opublikowano 29 marca 2024

Plan równości płci jako element budowania marki instytucji badawczej w kontekście employer branding

Introduction

Favourable opinions of employees of each organization about the employer are a key element of building its image and brand, referred to as employer branding (EB). The aim of this article is to present the possibility of using the issue of gender equality to build the brand of a research institution, especially in the context of EB. This problem is discussed based on the example of the results of a survey conducted by the staff of the Central Mining Institute-National Research Institute (GIG-PIB), carried out as part of the gender equality plan (GEP) developed in 2022. The study focuses on issues such as work–life balance, gender balance in management and decision-making, gender equality in recruitment and career development, gender mainstreaming in research and combating gender-based violence.

Brand Importance

A brand, as an attribute identifying companies, organizations or products, plays a fundamental role in the modern world. It is most often defined as ‘a name, term, symbol, pattern or a combination thereof, created to identify the goods or services of a seller or a group of goods or services and to distinguish them from the competition’ and, as Kotler and Keller (2012) emphasize, ‘it is not a stamp, but a kind of promise and promise that should shape the behavior and strategy of the company’. Depending on the need and type of organization or product, the brand has various functions: identification, warranty or promotion (Altkorn, 2001), although of course most often its task is to present the vision of the company to customers in such a way that it is easier for them to make purchasing decisions.

Kall (2006) defines a brand as ‘a combination of a physical product, a brand name, packaging, advertising, and accompanying distribution and price activities, a combination that, by distinguishing a marketer’s offer from competing offers, provides the consumer with distinctive functional and/or symbolic advantages, thereby creating a loyal group of buyers and thus enabling the achievement of a leading position in the market’. According to the AMA, a brand is ‘a name, term, mark, symbol or design, or combination thereof, intended to identify the goods or services of a retailer or group thereof and to distinguish them from those of competitors’. The key to creating a brand is the ability to choose a name, logotype, symbol, packaging design or other characteristics that will define the product and make it stand out from other goods. These different components of a brand that define and differentiate it are the elements of the brand (Keller, 2015).

The key to building a competitive advantage lies in the fact that the brand distinguishes the company’s offer from others; it is a promise of what can be expected from a given product or company (Pringle & Gordon, 2008). A measurable value for an organization is created by skilful brand management, that is, effective consolidation of the brand in the minds of recipients and making the product stand out among the offers of competitive brands (Patkowski, 2010).

One of the key tools for building brand recognition is brand image. It is defined either as ‘the set of meanings by which an object is known and by which people describe, remember, and relate to it’ (Dowling, 1986) or ‘the idea that one person or many audiences have of a person, company, or institution’ (Newsom et al., 1993). A brand can build its image in two ways. The first one is related to how managers want to present their company. The second one focuses on how the company is perceived externally and on public opinion, which are definitely more effective with product brands (Figiel, 2011). One of the functions of brand image, considered from the point of view of a company or organisation, is building the employer’s brand—an EB. In recent years, this English-language term has become a permanent fixture in the contemporary catalogue of marketing terms. The EB is a multifaceted activity of a company aimed at creating an image of an employer that is desirable in the labour market. It refers to the strategies and actions taken by organizations to build and promote their image as an attractive employer. One of its primary goals is to attract, engage and retain high-quality employees.

The term ‘Employer Branding’ was first used in the late 1990s (Ambler & Barrow, 1996) and popularized in 2001 by McKinsey (Axelrod et al., 2001). In the research conducted by Backhaus and Tikoo (2004), the term is understood as ‘the process of building an identifiable and unique identity of the employer’, while Sullivan (2004) considers it to be ‘a targeted long-term strategy for managing brand awareness and perception among employees, potential employees, and related stakeholders’. It allows for greater employee engagement, voluntary intellectual contributions, experiencing positive emotions and establishing better connections with other colleagues (Davies et al., 2018). Today, EB is also defined as a management strategy to retain current employees and attract new, relevant talent (Bussin & Mouton, 2019). Attracting and retaining talent as an effort by the employer is intended to support the achievement of the employer’s business goals (Rappaport et al., 2003). Kozłowski (2016) points out that EB is one of the few activities in a company that concerns its most sensitive areas, such as brand, human resources and finance, because due to the remuneration policy or marketing budget, it is difficult to treat these aspects as distinct and separate.

Another important aspect from the EB point of view is job satisfaction, as an employee’s emotional response to his or her specific job (Lambert et al., 2016) and a sense of satisfaction with the experience of the work performed (Owusu, 2014). EB is therefore strongly related to human resource management and involves striving for relevant goals such as attracting and retaining the most valuable employees who will ensure the company’s success and development, as well as reduce the costs of recruitment and employee turnover (Ober, 2016). However, it is not enough to create new jobs to attract workers. You have to make people want to fill them, so you must care about the candidate experience and treat them the same way you treat customers (Gojtowska, 2019).

Therefore, it can be concluded that EB is an activity whose core is focused on the company’s employees. The most frequently used tools in this area can include not only various types of benefits, incentive systems and development programmes, but also strategies supporting equality between women and men in the workplace. For scientific and research institutions, GEPs can be useful for EB.

Gender Equality in National and European Legislation

In the Constitution of the Republic of Poland of 1997 and the Labour Code, Article 183a, which is entirely devoted to the issue of equal treatment in employment (Labour Code, 2014), is the basic national legal act that prohibits discrimination on the grounds of sex and the obligation to implement the principle of equal opportunities for women and men. In terms of national documents, gender equality means that women and men are given the same social value, equal rights and obligations, as well as equal access to social resources (e.g. public services, labour market). This equality can be defined as a permanent situation in which both women and men have conditions that enable them to develop in their personal and professional areas and to make life choices that result from their personal needs, aspirations or talents (Ministry of Family and Social Policy, 2022).

The legal basis for gender equality of the European Union is enshrined in Article 3 of the Treaty on European Union as a fundamental European value (EC, 2003) and extended in the provisions of the European Pact for Gender Equality of 2011 (EC, 2011). However, the reports adopted by the European Commission show that progress in this area is very slow and that real gender equality has not yet been achieved. The European Union’s new strategy for smart, sustainable and inclusive growth, Europe 2020, aimed to achieve these objectives (EC, 2010).

The European Commission’s Gender Equality Strategy 2020–2025 is of particular importance for research institutions. One of the objectives of this strategy is to strengthen the European Research Area (ERA) and ensure equal opportunities in a work environment where everyone can develop talents equally. Article 7 of the Regulation of the European Parliament and of the Council establishing Horizon Europe is the Framework Programme for Research and Innovation, which refers to the need to ensure equal opportunities and gender mainstreaming in research and innovation content. Horizon Europe activities ‘should aim to eliminate gender bias and gender gaps, improve work–life balance and promote equality between women and men in research and innovation, including the principle of equal pay without discrimination based on sex’ (EC, 2021).

Methodology

The main objectives of the research were to develop a diagnosis of the state of gender equality and eliminate barriers to the implementation of these principles at the GIG-PIB, which was reflected in the GEP of the Chief Mining Inspectorate-National Research Institute developed on this basis.

The methodology of the work involved, in the first place, an analysis of existing data including: existing national and EU regulations, an analysis of the current situation in GIG-PIB in the field of equality between women and men, including: internal documents of GIG-PIB, the composition of advisory bodies of GIG-PIB, the structure of employment in GIG-PIB and an analysis of the remuneration of women and men in GIG-PIB, including academic staff, and a survey of all GIG-PIB employees, which was intended to give them an opportunity to express an opinion on equality issues. A detailed analysis of the provisions of 84 internal legal acts in force at the GIG was carried out, that is, orders, letters according to the distribution list and circular letters of the Director of the GIG as of Jan. 3, 2022 (at that time, the GIG did not yet have the status of NRI, which it obtained in 2023).

This article presents the results of a survey of all GIG-PIB employees, carried out using a computer-assisted web interviewing (CAWI) survey. The CAWI quantitative survey was conducted among all GIG-PIB employees from May 13 to 20, 2022. The questionnaire was addressed to 471 people employed at the Institute at that time on a full-time or part-time basis. The survey was completed by 182 people, of which 57.1% were men (104 people) and 42.9% were women (78 people). The survey was attended by a group that met the conditions of a representative sample, that is, 38.6% of all GIG-PIB employees.

Employees of different age groups took part in the survey. The largest groups constituted employees aged 41–50, who accounted for 31.3% of the total respondents, and employees aged 31–40, who accounted for 29.1% of the total. Employees aged 51–60 accounted for 18.1% and those over 60 years accounted for 17.03% of all respondents. The smallest group was the one with employees under 30 years of age accounting for 4.40%. The largest number of responses were received from persons employed at GIG-PIB in the range of 11–20 years (38.5%) and up to 10 years (29.7%). People with 21 years to 30 years of work experience accounted for 14.3%, and those over 30 years of age accounted for 17.6%.

When asked about belonging to the employee group, the highest number of responses was received from researchers (28.6%) and research and technical staff (17.0%). The group of engineering and technical employees accounted for 27.5%; administrative and economic employees, 24.9% and service employees, 2.7%. There was no response from workers in the ‘workers’ group.

Gender Equality in the Research Unit. Case Study of the GIG-PIB

To eliminate barriers to the implementation of the principle of gender equality at the Central Mining Institute and to develop the GIG GEP, detailed research was conducted in 2022 to collect knowledge and data on the state of gender equality at the Institute.

Analysis of Existing Data

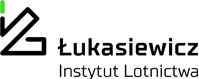

The employment structure at GIG-PIB has stabilized in recent years and amounts to about 500 people. Figure 1 shows the total number of employees in 2017–2021, broken down into women and men, and the percentage share of women in total employment. The share of women in employment at GIG-PIB has been around 38% in the last few years.

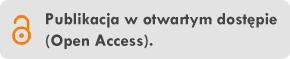

Since its inception, the GIG-PIB has been an industry research institute, where the main subject of work, since its establishment in 1925, has been scientific support for the mining sector, mainly hard coal mining. This has had an impact on the structure of employment at GIG-PIB, especially in the so-called ‘mining’ research and development plants. For these reasons, among others, there was a predominance of men in employment at GIG-PIB, which is still visible today and is shown in Figure 2. Currently, there are two scientific and research divisions in GIG-PIB: the geoengineering and industrial safety division (formerly ‘mining’) and the environmental engineering division.

With the average share of women in employment at GIG-PIB amounting to about 38%, there is a clear predominance of employed men in the geoengineering and industrial safety division—about 79% of total employment. There is an almost even distribution in the environmental engineering division, as women account for about 52% of the total workforce.

Survey Results

The substantive questions in the questionnaire were divided into five thematic areas:

- work–life balance,

- gender balance in management and decision-making bodies,

- gender equality in recruitment and career development,

- gender mainstreaming in the research process, and

- measures to combat gender-based violence.

The results of the survey in the area of work–life balance prove that employees have a positive attitude towards their work. In total, 84.6% of employees are of the opinion that they perform work at the Institute corresponding to their education. On average, 56% of employees spend between 8 hr and 10 hr a day at work, and 13.2% spend more than 10 hr a day. Almost half of the respondents (47.6%) have never experienced a situation in which they had to give up some aspects of their professional work necessary for career development due to private and/or family commitments. The most common examples of restricting working life were:

- resignation from foreign trips (13.7%),

- lack of publication of scientific articles (11.3%),

- lack of involvement in the life of the Institute (8.5%),

- resignation from participation in a research project (4.2%), and

- not deciding to take up a functional position (3.3%).

After analysing the answers obtained, the results in the group of women look similar. In total, 47.2% of women did not feel such limitations, and if they did, they mainly concerned trips abroad (12.4%), publishing scientific articles (11.2%) and engaging in the life of the Institute (7.9%). The vast majority of respondents believe that combining work with family life or caring responsibilities towards children or dependents in the family is not an obstacle to their professional work. This is shown in Figure 3 with the ratings, where a rating of 1 indicates that it is very difficult to reconcile work and family life to a very small extent and a rating of 5 is very high. Totally, 36.81% of people indicate a very low degree of handicaps, and 26.9% a low degree. The answers were similar for women: 34.6% of women indicated a very low degree and 30.8% indicated a low degree.

Out of the set of systemic facilitations existing at GIG-PIB, the greatest convenience in combining work and family life for the respondents is flexible working time (40.2%) and the ability to go out during work time to deal with private matters (35%). However, the majority of GIG-PIB employees do not make full use of their annual leave during the year (58.8%), and during their holidays, they answer business phone calls and regularly check emails and answer business emails; they also work professionally on weekends (55.2%). It should be concluded that the facilities in combining professional work with family life are a significant support, for the employees of the Institute, allowing them to take care of the development of their scientific/professional careers, which is definitely an element conducive to building EB. On the other hand, the amount of unused leave may indicate excessive involvement of employees in their professional duties, or an ineffective system of organizing substitution during absences, which in turn indicates that professional matters permeate private life.

When asked about gender balance in management and decision-making bodies, 79.9% of GIG-PIB employees believe that women and men have equal access to participation in management and decision-making bodies, and 81.3% of respondents believe that gender does not matter for the performance of a managerial responsibilities. Totally, 85.7% of GIG-PIB employees are of the opinion that promotion opportunities are the same for all employees of the Institute; only 6% of the respondents answered that they had encountered discrimination when planning their research career at GIG-PIB, but none of the respondents indicated what the specific forms of this discrimination were. These results show that almost all employees have a positive perception of promotion opportunities at the Institute and do not feel barriers based on gender.

When asked about the general reasons for unequal treatment of men and women in professional promotions, the most frequently mentioned were:

- higher family burden on women due to their family situation and having children (17 indications),

- stereotypical thinking and traditional images of women and men (16 indications),

- pragmatism (e.g. women are less available) (10 responses),

- physical predispositions and biological–psychological issues (e.g. women are weaker and unable to make rational decisions, they are guided by emotions) (8 indications),

- history and tradition in perceiving mining and industry as a male domain (8 indications),

- restrictions and glass ceiling for women (4 indications), and

- obsolete management model (2 indications).

Other examples include being driven by sympathy instead of experience and competence and the fear of male staff when it turns out that women have an intellectual or expert advantage in public situations. Such results indicate that it is necessary to analyse the emerging discrepancies on an ongoing basis, and this can be achieved by developing a development path for employees, taking into account the individual potential of each of them.

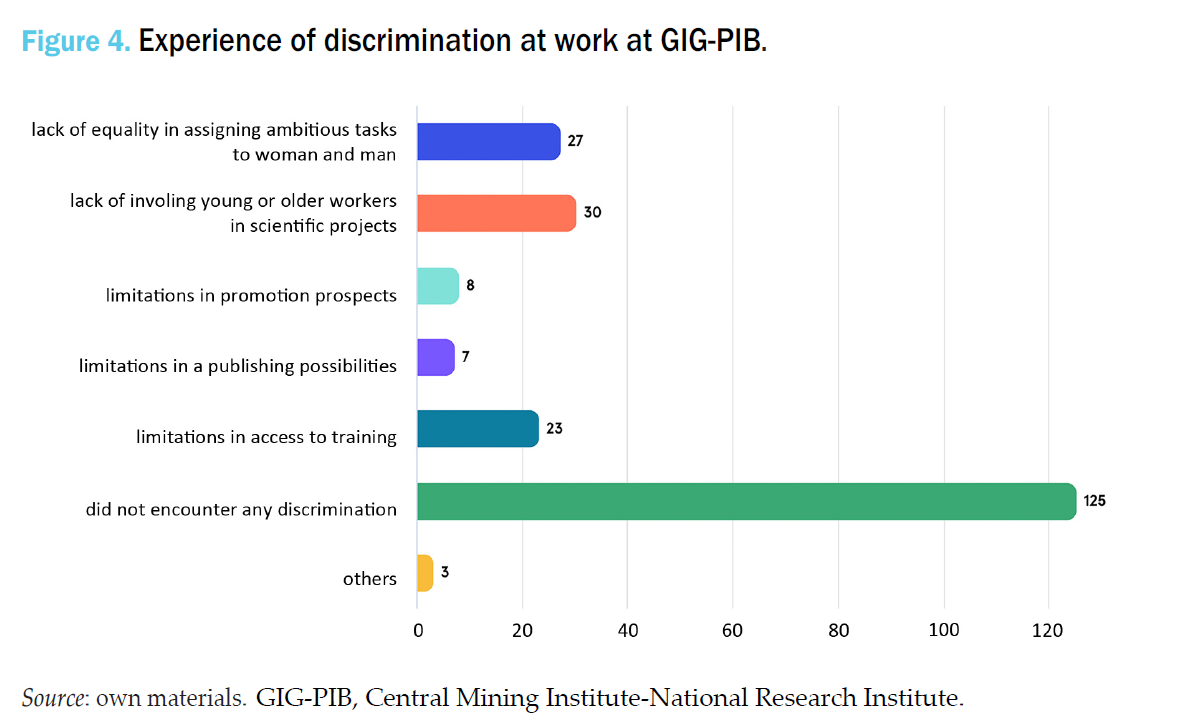

When asked about gender equality in the recruitment and career development process, it turned out that 56% of the respondents did not encounter any discrimination while working at GIG-PIB. Totally, 13.4% of the respondents experienced a situation where young or older workers were not involved in scientific projects, 12.1% experienced a lack of equality in assigning ambitious tasks to women and men and 10.3% experienced limitations in access to training. The extent of limitations to career development is shown in Figure 4.

When asked about the gender pay gap, 65.4% of respondents believe that they have no knowledge of the gender pay gap in the same or similar positions. In total, 20.3% of respondents believe that they are comparable, and 12.6% believe that women’s earnings are lower. Due to the confidentiality of information on the earnings of individual employees, the answers were intuitive.

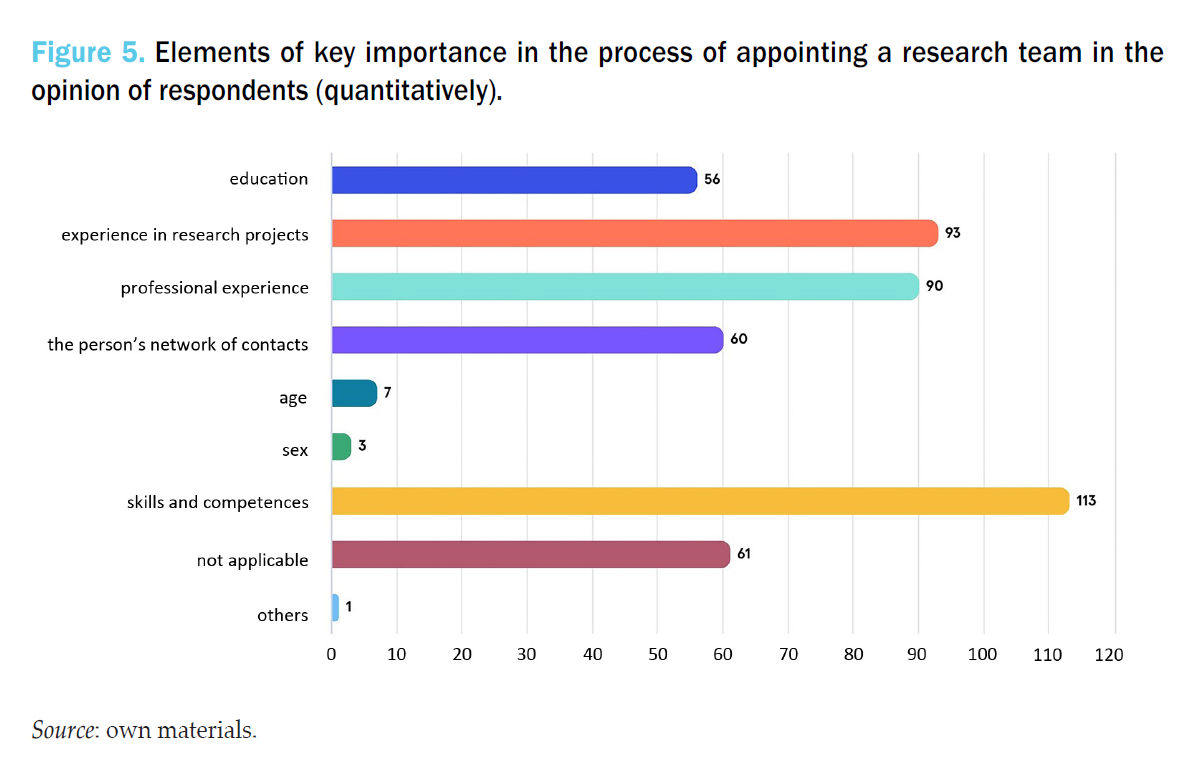

When it comes to the main questions concerning the thematic area related to gender mainstreaming in the research process, 69.2% of the respondents expressed the opinion that they had not encountered any gender-based discrimination in the GIG-PIB regarding access to participation in research projects. This means that every employee has the same access to scientific development through participation in research projects. The key criteria for this participation are competences and skills. This is confirmed by the answers obtained in the next question concerning the appointment of the project’s research team. As Figure 5 shows, respondents declare that in this case they mainly take into account:

- skills and competences—23.3%,

- experience in research projects—19.2%,

- professional experience—18.6%,

- the person’s network of contacts—12.4%, and

- education—11.6%.

When analysing the responses to their general experiences of combating gender-based violence, almost 79% of respondents say that they have not encountered gender stereotypes and prejudices while working. However, in the case of any manifestations of violence, the following were most often indicated:

- comments or jokes that refer to stereotypical beliefs about gender (24%),

- sexually suggestive comments or jokes (19.1%),

- verbal aggression (6.9%),

- harassment (4.6%), and

- persecution based on gender and sexual preferences (1.5%).

The data presented above are shown in Figure 6.

In the case of experiencing gender-based violence, two people turned to the management of the Institute (1.1%), 18.5% coped on their own and 79.3% are of the opinion that this problem does not apply to them, which probably means that they have not encountered such a situation. Since the Institute has procedures in place to limit such negative activities, the question was asked about the degree of their awareness. Totally, 76.4% of respondents declared that they were familiar with the existing regulations in the GIG-PIB related to the areas of counteracting manifestations of violence, such as: the work regulations, the antimobbing and antidiscrimination procedure in GIG-PIB and the Code of Ethics for employees of GIG-PIB.

Further internal actions to raise awareness of equality issues and reduce stereotypes in the perception of female and male roles, with particular emphasis on language, should be considered advisable. An open, inclusive workplace is extremely important from the point of view of the brand of a good employer who cares about the well-being of its employees and eliminates undesirable behaviours.

Conclusions

The analysis showed that the vast majority of employees, both women and men, positively assess the working conditions at the Institute. The research allowed to gather knowledge and data necessary to develop the GEP for GIG-PIB, the ultimate goal of which is to provide all employees of the Institute with equal opportunities for professional, scientific and personal development, while combating and reducing gender disparities and inequalities. The GIG GEP 2022–2026 formulates key principles, objectives and measures to promote equal opportunities for all employees of the Institute, regardless of their gender. Its aim is to promote equal opportunities for women and men in professional life at the Institute, including free academic and personal development. This also includes measures to reduce the under-representation of women, avoid gender disadvantages, ensure equal employment and optimise work–family balance for the Institute’s staff.

Such activities support the efforts made by GIG-PIB to build EB and consolidate the image of an attractive employer, hoping to attract and retain valuable employees, due to which such a special type of entity as a research institution develops. The obtained results allow them to be used in the implementation of the Institute’s strategy, both in terms of human resources management and the awareness and perception of the GIG-PIB brand by current and potential employees.

The situation assessed by the respondents of the survey as positive may be an element of building a competitive advantage, based on the brand of the institution and the brand of the employer, as the one who gives equal opportunities for development to women and men. Therefore, the GEPs can be an effective tool to support the achievement of these goals.

Internally, EB is an activity whose core is focused on the company’s current employees. GEPs may be useful for research units as tools supporting equality between women and men in the workplace, allowing for the improvement of employees and thus creating competitive advantages and achieving strategic goals such as development and profit.

References

1.Altkorn, J. (2001). Strategia marki. PWE Warszawa.

2.Ambler, T., & Barrow, S. (1996). The Employer Brand. Journal of Brand Management, 4(3), 185–206.

3.Axelrod, E. L., Handfield-Jones, H., & Welsh, T. A. (2001). War for talent (part 2), The Mckinsey Quarterly, 2, 9–12.

4.Backhaus, K., & Tikoo, S. (2004). Conceptualizing and researching employer branding. Career Development International, 9(5), 501–517.

5.Bussin, M., & Mouton, H. (2019). Effectiveness of Employer Branding on staff retention and compensation expectations. South African Journal of Economic and Management Sciences, 22(1), 1–9. doi: 10.4102/sajems.v22i1.2412

6.Davies, G., Mete, M., & Whelan, S. (2018). When Employer Brand image aids employee satisfaction and engagement. Journal of Organizational Effectiveness, 5(1), 64–80. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOEPP-03-2017-0028

7.Dowling, G. R. (1986). Managing your corporate images. Industrial Marketing Management, 15(2), 109–115.

8.Figiel, A. (2011). Czym jest wizerunek przedsiębiorstwa: próba- zidentyfikowania. Ekonomiczne problemy usług, 74, 83–95.

9.Gojtowska, M. (2019). Candidate experience. Jeszcze kandydat czy już klient? Wolters Kluwer.

10.Kall, J. (2006). Jak zbudować silną markę od podstaw. One Press.

11.Keller, K. (2015). Strategiczne zarządzanie marką. Oficyna Wolter Kluwer.

12.Obwieszczenie Marszałka Sejmu Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej z dnia 17 września 2014 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia jednolitego tekstu ustawy – Kodeks pracy, No. Dz.U. 2014 poz. 1502 (2014). https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/ WDU20140001502/O/D20141502.pdf 13.Traktat o Unii Europejskiej. No. 5866 — Poz. 864 (2003). https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/ isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU20040900864/O/D20040864.pdf

14.Komisja Europejska (2010). EUROPA 2020 Strategia na rzecz inteligentnego i zrównoważonego rozwoju sprzyjającego włączeniu społecznemu, Komunikat (KOM (2010) 2020 wersja ostateczna), Bruksela 3.3.2010. https://ec.europa.eu/eu2020/ pdf/1_PL_ACT_part1_v1.pdf

15.Komisja Europejska, K. E. (2011). Europejski Pakt na rzecz Równości Płci (Dz. Urz. UE C 155 z 25.05.2011). https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/?uri= CELEX%3A52011XG0525%2801%29

16.Komisja Europejska, K. E. (2021). Rozporządzenie Parlamentu Europejskiego i Rady (EU) 2021/695 z dnia 28.04.2021 r. ustanawiające program ramowy w zakresie badań naukowych i innowacji Horyzont Europa. https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/PL/TXT/PDF/?uri=CELEX:32021R0695&from=PL

17.Konstytucja Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej 1997 (Dz. U. z 1997 r. nr 78, poz. 483, z późn. zm.). https://isap.sejm.gov.pl/isap.nsf/download.xsp/WDU19970780483 /O/D19970483.pdf

18.Kotler, P., & Keller, K. (2012). Marketing. Rebis.

19.Kozłowski, M. (2016). Employer branding. Budowanie wizerunku pracodawcy krok po kroku. Wolters Kluwer.

20.Lambert, E. G., Minor, K. I., Wells, J. B., & Hogan, N. L. (2016). Social support’s relationship to correctional staff job stress, job involvement, job satisfaction, and organizational commitment. Social Science Journal, 53(1), 22–32. doi: 10.1016/j.soscij.2015.10.001

21.Ministerstwo Rodziny i Polityki Społecznej (2022). Krajowy Program Działań na Rzecz Równego Traktowania na lata 2022-2030. https://www.gov.pl/web/ rownetraktowanie/aktualizacja-krajowy-program-dzialan-na-rzecz-rownego-traktowania-na-lata-2022-2030

22.Newsom, D., Scott, A., & Van Slyke, T. J. (1993). This is public relations. The realities of public relations. Wadsworth Publishing Company.

23.Ober, J. (2016). Employer Branding – strategia sukcesu organizacji w nowoczesnej gospodarce. Zeszyty Naukowe. Organizacja i Zarządzanie, 95, 345–356.

24.Owusu, B. (2014). An assessment of job satisfaction and its effect on employees’ performance: A case of mining companies in the Bibiani- Anhwiaso – Bekwai District in the Western Region. Knust, 1–97, ibidem.

25.Patkowski, P. (2010). Potencjał konkurencyjny marki. Jak zdobyć przewagę na rynku. Poltext.

26.Pringle, H., & Gordon, W. (2008). Zarządzanie marką. Rebis.

27.Rappaport, A., Bancroft, E., & Okum, L. (2003). The aging workforce raises new talent management issues for employers. Journal of Organizational Excellence, 23(1), 55–66. doi: 10.1002/npr.10101

28.Sullivan, J. (2004). Eight elements of a successful employment brand.

https://www.ere.net/the-8-elements-of-a-successful-employment-brand/

Sylwia Jarosławska-Sobór — Accomplished PR and communication professional with many years of practical experience. In her scientific work focused on social aspects of business operation. PhD awarded by the Polish Ministry of Family, Labour and Social Policy. Member of Silesian Centre for Business Ethic and Sustainable Development. Member of programming and monitoring sustainable development team of the Observatory of Urban and Metropolitan Processes.