- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Kształtowanie nowego produktu z perspektywy tworzenia przewagi konkurencyjnej

Dariusz Dąbrowski*

Marketing Department, Gdańsk University of Technology, Faculty of Management and Economics,

Narutowicza 11/12, 80-233 Gdańsk, Poland

*E-mail: dariusz.dabrowski@zie.pg.gda.pl

ORCID: 0000-0002-2045-2683

Abstrakt:

Uznaje się, że osiągnięcie przewagi konkurencyjnej opartej na produkcie jest kluczowym zadaniem dla przedsiębiorstwa. Niemniej jednak, istnieje nadal luka badawcza dotycząca wskazania konkretnych działań w procesie rozwoju nowego produktu, które wynikają z dążenia przedsiębiorstw do osiągnięcia przewagi konkurencyjnej opartej na produkcie. W związku z tym, celem pracy jest określenie specyficznych działań w procesie rozwoju nowego produktu (RNP), które wynikają z zamiaru przedsiębiorstwa do wprowadzenia na rynek nowego produktu, umożliwiającego osiągnięcie przewagi konkurencyjnej. Podstawową metodą badawczą zastosowaną w pracy jest metoda dedukcji, a jako metodę dodatkową wykorzystano badanie literatury. Rezultatem pracy jest zaproponowanie trzech rodzajów działań: a) ocenę sposobności po względem generowania na jej podstawie przewagi konkurencyjnej, b) tworzenie nowego produktu o jak najwyższej wartości ekonomicznej, c) ocenę zarówno planowanego nowego produktu, jak i nowego produktu po wprowadzeniu na rynek pod względem osiągania przewagi konkurencyjnej. Ostanie dwa rodzaje działań mogą być podejmowane na różnych etapach procesu rozwoju nowego produktu i dotyczyć samej koncepcji nowego produktu, jak i określonych form tego produktu (np. prototypu, produktów serii próbnej).

Zaproponowane działania mają istotne znaczenie, ponieważ osiągnięcie przewagi konkurencyjnej opartej na produkcie przyczynia się do realizacji innych celów związanych z nowymi produktami (np. generowania przychodów ze sprzedaży). Dlatego też zaleca się uwzględnienie tych działań przez przedsiębiorstwa w procesie rozwoju nowych produktów. Praca wnosi wkład do obszaru zarządzania, poprzez zaproponowanie konkretnych działań w poszczególnych fazach procesu rozwoju nowego produktu, wynikających z intencji przedsiębiorstwa do osiągnięcia przewagi konkurencyjnej opartej na produkcie — co dotychczas brakowało w literaturze.

MINIB, 2023, Vol. 49, Issue 3

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0019

Str. 141-158

Opublikowano 15 września 2023

Kształtowanie nowego produktu z perspektywy tworzenia przewagi konkurencyjnej

Introduction

The development of new products is essential for a company, because customers are open to new products that will increasingly meet their needs. From the customers’ perspective, there is no qualitative limit in meeting their needs. The development of new products is also supported by technical progress, which enables the creation of products that meet customer needs to a greater extent than do current products. This situation makes new products a vital resource through which companies compete with each other (Cooper, 2018). This is evidenced by the relatively high expenditure incurred by enterprises on developing new products, as they account for approximately 12.4% of sales revenues (Lee & Markham, 2016).

However, developing new products is risky because not all new products introduced to the market achieve their goals. It turns out that about 39% of new products launched on the market are so-called „failures” (Lee & Markham, 2016); the primary sources of failure of new products are market uncertainty and technological uncertainty (Dhebar, 2016). The first concerns the difficulty of predicting the market situation after the launch of a product, such as the uncertainty of how customers perceive the benefits offered by a new product. The second source of failure concerns the uncertainty regarding the expected functioning of new technical solutions, such as the uncertainty of achieving a certain level of cost of a new product.

Due to factors such as the need to introduce new products to the market, and the relatively high level of both risk and the development costs of new products, it is valid to look for ways to increase the chances of introducing new products to the market, which allows the achievement of the planned goals. One such solution is to focus the process of developing new products on creating a competitive advantage based on a new product.

The approach to developing new products proposed in the paper is based on the assumption that the overriding goal of this activity is to introduce a new product to the market that will allow a company to achieve a competitive advantage. This assumption can be justified by the fact that when choosing a particular product, customers are guided by seeking the highest possible buyer surplus, which is the difference between the benefits perceived by customers from using the product (furthermore, also referred to as customer-perceived benefits of product usage) and its price (Peteraf & Barney, 2003). The highest buyer surplus can be offered by the supplier that has a competitive advantage based on the product. As a result, by offering the highest surplus to the buyer, a company can encourage customers to buy a new product. This situation, in turn, supports the achievement of other goals of the new product, such as certain sales revenues or a certain market share. This assumption is consistent with the observation made by Nayak et al. (2022), who argue that competitive advantage is an overarching concept related to company performance.

Considering these factors, this work is devoted to presenting an approach to the development of new products aimed at creating a competitive advantage. The work aims to define the specific actions in the process of developing new products, which result from a company’s intention to introduce to the market a new product that will enable it to achieve a competitive advantage. Many researchers have already noticed the significance of a competitive advantage in developing new products. This is evidenced by the results of meta-analyses (Evanschitzky et al., 2012; Henard & Szymanski, 2001), which indicate that competitive advantage based on the product positively affects the outcomes achieved through new products. However, a review of domestic literature (e.g., Dąbrowski, 2009; Rutkowski, 2007; Sojkin, 2003; Sosnowska, 2003) and foreign literature (e.g., Cooper, 2017; Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Garcia, 2014; Kahn, 2001) suggests that there is still a research gap regarding the identification of specific actions resulting from the intention of a company to achieve a product-based competitive advantage at various stages of the new product development (NPD) process.

The methodology of work consists of deduction and literature study. The deduction method was used to determine the critical actions of interest to the work. The deduction was carried out according to the following scheme: if a company aims to achieve a competitive advantage based on a new product, then what specific actions will be needed in the process of developing a new product? The deduction method was supported by the literature review that was used primarily to define the fundamental concepts of the paper and at every stage of the work whenever necessary.

Concerning the aim of this work, the following terms can be considered as fundamental concepts: new product, NPD, and competitive advantage. The first two have been defined based on the dictionary developed by the Product Development and Management Association (Kahn, 2013). Thus, a new product is understood as „a product (either a good or service) new to the firm marketing it” (Kahn, 2013, p. 595), while NPD is defined as „the overall process of strategy, organization, concept generation, product and marketing plan creation and evaluation, and commercialization of a new product” (Kahn, 2013, p. 595). The other part of the work presents the understanding of competitive advantage.

The paper first focusses on explaining the essence of a competitive advantage based on a product and presents the fundamental issues regarding the estimation of this advantage. Then, through deduction, specific actions — which result from focussing this process on achieving a competitive advantage — for the process of developing new products are proposed.

Competitive Advantage Based

on a Product and Its Estimation

The concept of competitive advantage, introduced by Porter (1985), is related to the phenomenon of competition, which is one of the relations between enterprises operating in a given market. The essence of competition can be considered as enterprise-undertaken actions that result from pursuing the antagonistic goals of these enterprises (Mantura, 2009). A classic example of this phenomenon is a situation where several companies take certain actions to satisfy a specific need of the same group of buyers. The competition itself is based on the so-called instruments of competition, also known as factors or criteria of competitiveness (Gorynia, 2009; Sopińska, 2009), which may be, for example, machinery, patents, products, or financial resources. A company’s competitive advantages or weaknesses can be distinguished based on the instruments of competition. Compared to its competitors, competitive advantage occurs when an enterprise is characterised by a higher level of a specific factor of competitiveness, whereas weakness occurs when the level of a particular factor is lower than its competitors (Mantura, 2009). Obłój (2007) argues that a company can have both competitive advantages and weaknesses even within the same area.

The product is an important instrument of competition for enterprises, as it is the basis for creating certain customer benefits. The benefits refer to the advantages or positive outcomes customers gain when using a product (Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Kotler et al., 2018). According to the resource-based view, the product is considered an enterprise’s resource, which can be a source of its competitive advantage (Barney & Hesterly, 2012). Thus, the issue of product-based competitive advantage is essential, which stems from the concept of economic value. Based on previous work on supply chain value creation (e.g., Brandenburger & Stuart, 1996), Peteraf and Barney (2003) define economic value in the following way: „The economic value created by an enterprise in the course of providing a good or service is the difference between the perceived benefits gained by the purchasers of the good and the economic cost to the enterprise” (Peteraf & Barney, 2003, p. 314). At the same time, these benefits perceived by the buyer are conveyed by the price that the customer is willing to pay for the product, which is also called the upper price limit (Cerda & García, 2021; Peteraf & Barney, 2003). Economic value is understood in a similar way in other research works (e.g., Barney, 2018; Costa et al., 2013). A company shares the generated economic value with a customer based on the price through a buy-sell transaction. Therefore, each party takes a part of the economic value, and the part captured by the buyer is called the consumer (buyer) surplus. The part captured by the producer of the product is called producer (supplier) surplus. Buyer surplus is the difference between the customer-perceived benefits of product usage and the product’s price, and producer surplus is the difference between the product’s price and its economic costs. Thus, the economic value is independent of the product’s price (Peteraf & Barney, 2003).

To define competitive advantage, the concept proposed by Peteraf and Barney (2003), as modified by Barney and Hesterly (2012), is used. Peteraf and Barney (2003) defined competitive advantage — concerning a specific product sold on a particular market — as follows: „An enterprise has a competitive advantage if it is able to create more economic value than the marginal (breakeven) competitor in its product market” (Peteraf & Barney, 2003, p. 314). According to this approach, the point of reference in determining competitive advantage is the marginal competitor, understood as the least-efficient company operating on the market yet still profitable. Barney and Hesterly (2012) modified this definition. They assumed that any competitor for a given product could be the point of reference. Thus, the definition of competitive advantage presented by these authors is as follows: „In general, a firm has a competitive advantage when it is able to create more economic value than rival firms” (Barney & Hesterly, 2012, p. 28). The latter approach seems accurate, as it allows a comparison of any two competitors, indicating which of them has a competitive advantage. Consequently, the understanding of competitive advantage following the concept of Peteraf and Barney (2003) was adopted in the paper, however, taking into account the modification of the reference point introduced by Barney and Hesterly (2012).

If the intention to achieve a competitive advantage is taken as the overriding goal of NPD, then the issue of determining this advantage becomes essential. Therefore, attention is now focussed on estimating competitive advantage, which was the subject of the author’s earlier work (Dąbrowski, 2022a). Assuming that a new product and a specific competing product are considered, the problem of determining the competitive advantage comes down to determining the economic value of both the new and the competing products. And to determine the economic value, information about the customer-perceived benefits of product usage and its costs is necessary. The idea of determining the competitive advantage is presented in Figure 1.

As for the customer-perceived benefits of product usage, they are conveyed by the price that buyers are still willing to pay for the product, expressed as the upper price limit, as has already been discussed. The upper price limit may be determined through price research, which can be carried out in various ways. For example, first, buyers can be asked explicitly about the upper price limit for the product. Second, a series of dichotomous questions with „yes” or „no” answers may be used, with subsequent questions asking for a higher and higher price. Third, a price sensitivity measurement can be used. Concerning the latter, the respondents are asked to provide four price levels, one of which — expressed by the phrase „expensive, but its price is still acceptable” — indicates the upper price limit (Dąbrowski, 2022a; Kaczmarczyk, 2016; Waniowski, 2005). Based on the price research, an upper price limit can be set for both the competitor and the new product. However, in the latter case, it can be done in relation to a new product launched on the market or in relation to its earlier forms, such as the new product concept, the prototype, or trial production products.

When it comes to product costs, they can be estimated in the case of a competing product as follows: first, based on the price of the competing product and the average cost of overheads used in a given industry; and second, according to the construction and technological solutions used in the competing product. In the case of a new product, the method of determining these costs will depend on whether a new product concept or a functioning product is being considered. Concerning the concept of a new product, its costs can be estimated based on its planned design and technology or according to historical data on the costs of a similar product. When there is already a functioning new product (e.g., a prototype), the costs of the new product can be updated to the level of knowledge consistent with the current stage of development of the new product. This means that information on costs can be used for the prototype, then for the trial production products, and subsequently, for the new product launched on the market (Dąbrowski, 2022a).

Specific Actions in the Development

of New Products Aimed at Achieving a Competitive Advantage

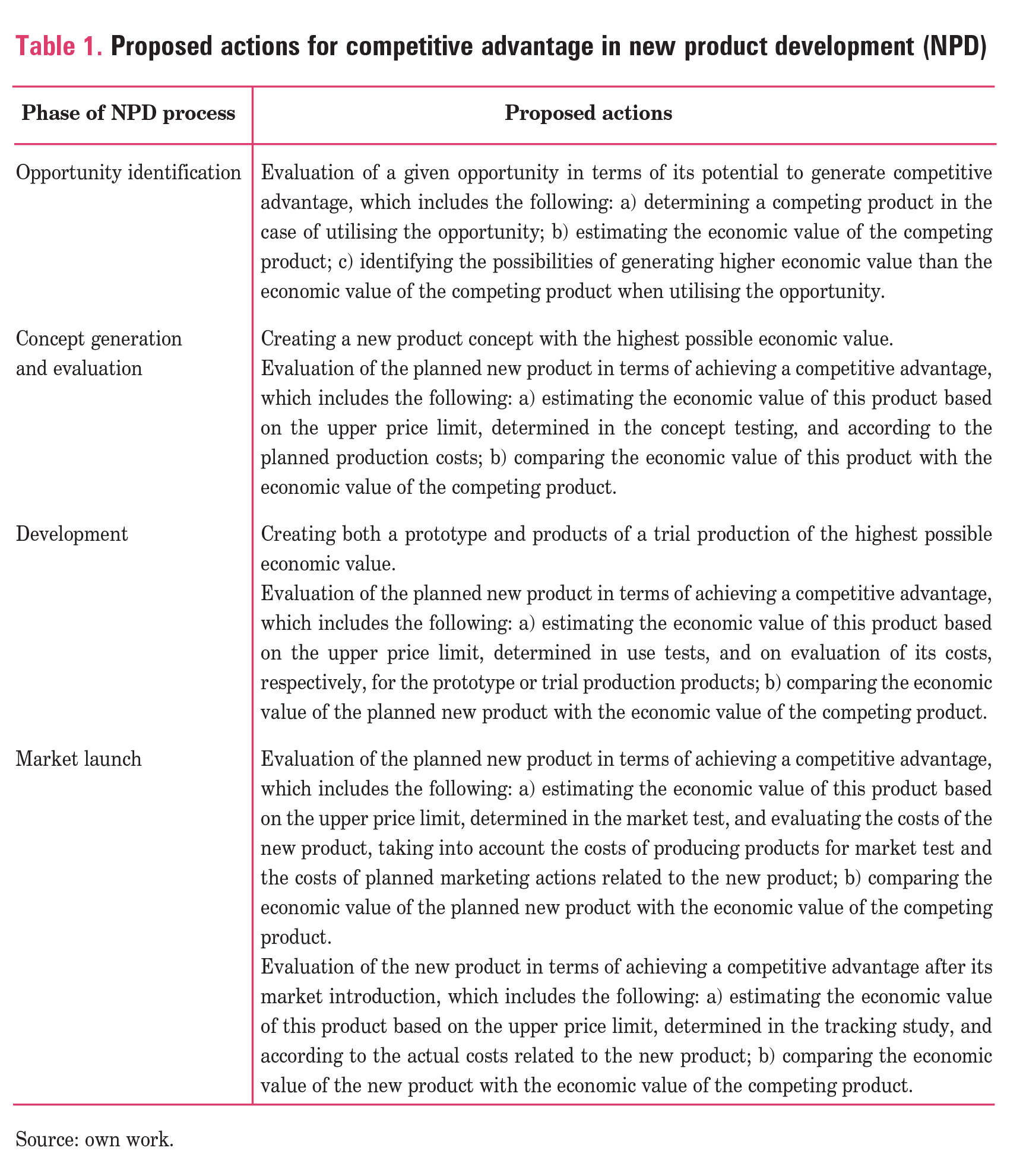

The actions mentioned in the title of this chapter were determined based on deduction, the inference scheme of which has been presented in the Introduction section. These actions were identified based on the following four phases of the NPD process: opportunity identification, concept generation and evaluation, development, and market launch. The adopted four-phase description of the NPD process is based on the approach of Crawford and Di Benedetto (2011), who distinguish five phases. However, a modification has been made to the framework proposed by these authors, which involves combining the second phase (concept generation) and the third phase (concept evaluation), as their focus is on the concept of the new product. The adopted four-phase approach to describing the NPD process is sufficient to achieve the goal and according to the scope of the presented work.

In the following sections, in reference to each phase of the NPD process, first the characterisation of a given phase based on literature sources is presented, and then specific actions within its scope are proposed, which form the subject of this work. The actions obtained in this way are summarised in Table 1.

The opportunity identification phase involves searching for an opportunity to introduce a new product to the market, including recognising (or creating) it and understanding the market and requirements related to the opportunity (Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Kahn, 2001). In the context of developing new products, an opportunity is perceived as a gap between the current and anticipated market situations that allows for the development of a new product (Kahn, 2013). This gap is typically of a market or technical nature, and diagnosing it requires information about both the current and future market situations (Dąbrowski, 2010).

In this phase, if a company aims to achieve a competitive advantage based on a new product, then it is proposed to conduct an assessment of the opportunity in terms of its potential to generate competitive advantage. This assessment may involve three key actions. The first action is to identify a competing product with which the company would compete if the opportunity is pursued. The second action involves estimating the economic value of the competing product, which can be done following the procedure presented in section on „Competitive Advantage Based on a Product and Its Estimation” (including determining the upper price limit and estimating the costs of the competing product). The third action involves exploring the potential to generate higher economic value based on the opportunity compared to the economic value of the competing product. In this exploration, attention can be paid to possibilities such as increasing the benefits offered to potential buyers, reducing production costs, applying new manufacturing technologies, or adopting a competitive business model.

In the concept generation and evaluation phase, two primary actions take place: first, defining the concept of the new product, and second, conducting an evaluation of that concept (e.g., market, technical, and economic aspects). This phase concludes with the preparation of the product protocol, which includes a development plan for the new product (Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Kahn, 2001). Recently, the author has proposed expanding the first of these actions to include proposing the business model of the new product, as the success of the new product is influenced not only by the product itself but also by the other components of its business model (Dąbrowski, 2022b).

In this phase, if a company aims to create a new product that enables it to achieve competitive advantage, the following specific actions can be proposed: a) creating a new product concept with the highest possible economic value, and b) conducting an assessment of the planned new product in terms of achieving competitive advantage. In the first action, maximising the economic value of the new product will be facilitated by offering customers the highest possible benefits from using the product while striving to minimise the costs of the new product. In the second action, the planned new product should be evaluated to determine its ability to achieve a competitive advantage. Specifically, whether the economic value of the planned new product exceeds that of the competing product should be checked. To conduct this assessment, the economic value of the planned product needs to be estimated. The economic value of the competing product has already been determined in the previous phase. The estimation of the economic value of the planned product can be done using the procedures presented in the section on „Competitive Advantage Based on a Product and Its Estimation”. In particular, during the concept testing, conducted in the current phase, the upper price limit of the planned new product can be determined. The costs of the planned new product can be estimated using one of the methods presented in the section on „Competitive Advantage Based on a Product and Its Estimation”.

In the development phase, the key actions include the following: a) preparing a prototype and conducting its laboratory and use testing; b) developing the product and its manufacturing technologies; c) carrying out a trial production (also known as pilot production) and conducting laboratory and use testing on the products from the trial production; and d) preparing a marketing action plan and refining the business model (Cooper, 2017; Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Dąbrowski, 2022b; Kahn, 2001).

If a company aims to achieve a competitive advantage based on the planned new product, the following specific actions can be proposed in the development phase: a) developing both the prototype and the products from the trial production to have the highest possible economic value — this can be achieved, similar to the previous phase, by striving to offer the highest benefits to customers while minimising the product costs; b) checking, based on the results obtained in this phase, whether the planned new product enables gaining a competitive advantage. The key outcomes of this phase are a prototype and products from the trial production. Therefore, estimating the economic value of the planned product first based on the prototype and then based on the products from the trial production is recommended. In both cases, the upper price limit of the planned new product can be estimated through product use testing, whereas the costs of this product can be evaluated first based on the prototype production costs and then based on the production costs of the products from the trial production.

During the market launch phase, the following key actions take place: conducting market test of the new product, initiating production and commencing sales, monitoring the market situation and taking corrective actions if necessary. The market test serves as the final evaluation, during which marketing plans and certain components of the business model are tested, in addition to the product itself (Cooper, 2017; Crawford & Di Benedetto, 2011; Dąbrowski, 2022b; Kahn, 2001).

In the market launch phase, if a company’s intention is to achieve a competitive advantage based on a new product, conducting an assessment in terms of attaining competitive advantage for both the planned new product and the new product itself is proposed. In the first case, the estimation of the economic value of the planned new product can be conducted as follows: the upper price limit of the product can be determined based on the market test, while the cost assessment can be based on the production costs for the market test, costs of planned marketing actions, and costs of implementing the planned components of the business model. In the second case, concerning the actual new product, the evaluation of the new product takes place after its introduction to the market, and in this scenario, the estimation of its economic value can be based on the upper price limit of the new product, which can be determined through tracking studies (that take place at this stage), and the actual costs of the product.

Two additional issues related to the above proposed actions in the NPD process, from the perspective of achieving a competitive advantage, are also discussed herein.

In the second, third, and fourth phases of the analysed process, evaluations of the planned new product in terms of achieving competitive advantage have been proposed. These evaluations should become increasingly reliable in subsequent phases because, as the development work progresses, the new product, its business model, and planned marketing actions become more refined. As a result, in a given phase compared to the previous one, the quality of information regarding the upper price limit of the planned new product, its costs, and the assessment of achieving competitive advantage improves.

In each phase, appropriate decisions should be made based on the actions proposed that are outlined in Table 1. If it is determined in the first phase that a particular opportunity has no potential for generating a competitive advantage, alternative opportunities should be considered. If it is found in subsequent phases that the economic value of the planned new product does not exceed the economic value of the competing product, adjustments to the product itself or the business model are necessary. After implementing these adjustments, the planned new product should be reassessed in terms of achieving a competitive advantage.

Summary and Conclusions

The work is based on the assumption that the main objective of creating a new product is to achieve a competitive advantage based on the product. Therefore, it is essential to identify specific actions in the process of developing a new product that will enable the achievement of this competitive advantage. The actions have been proposed using the deductive method and lead to the presentation of the following types of actions:

1) evaluation of an opportunity in terms of its potential to generate competitive advantage; 2) creation of a new product with the highest economic value; 3) evaluation of both the planned new product and the actual new product in terms of achieving a competitive advantage. The concise characteristics of each of these types of actions are presented as a summary.

The first type of actions includes determining the competing product in case a particular opportunity is utilised, estimating the economic value of that competing product, and identifying the potential to generate higher economic value based on that opportunity compared to the competing product. The purpose of these actions is to find opportunities with the greatest potential for creating a competitive advantage based on the product.

The second type of actions pertains to creating a new product with the highest possible economic value and encompasses both the concept of the new product and the product itself, which can take the form of a prototype or a trial production product. Creating a product with the highest economic value involves developing a product that provides customers with maximum benefits while simultaneously minimising its costs.

The third type of actions concerns the evaluation of the new product both during its development and after its introduction to the market in terms of achieving a competitive advantage. This evaluation involves comparing the economic value of the new product with the economic value of the competing product and serves as a form of control that takes place during the development process and after the new product is launched. In the case of the planned new product, this evaluation can be conducted based on various forms, such as the product concept, prototype, trial production products, and products produced for market test.

The quality of information regarding the new product-based competitive advantage improves as the NPD work progresses. This is because the progress in development leads to a better refinement of the new product, its business model, and planned marketing actions. Consequently, as the development work advances, there is an increase in the reliability of information used to estimate the economic value of the new product, including its cost and the upper price limit.

Regarding the upper price limit, market research conducted in the subsequent phases of the NPD process to determine this limit allow for the creation of conditions that more closely resemble those encountered during the actual sale of the new product. For example, in the use tests, which occur during the development phase, potential buyers interact with the actual product (e.g., prototypes, trail production products) rather than just its concept, which is the subject of concept testing conducted during the concept generation-and-evaluation phase. Furthermore, during the market testing of the new product in the market launch phase, the aforementioned upper price limit can be established based on the actual product, taking into account planned marketing actions and selected aspects of its business model.

As a result, the quality of information regarding both the economic value of the new product and its competitive advantage increases as the development effort progresses.

When it comes to evaluating an actual new product in terms of achieving competitive advantage after its market introduction, it is conducted taking into account both the actual business model and the implemented marketing actions. At this stage, the quality of information regarding the economic value of the new product (including information about its upper price limit and costs) as well as the product-based competitive advantage will be at its highest.

For the purpose of this work, four phases have been distinguished in the process of developing new products. However, in practice, the number of these phases may vary depending on the type of new product project, the type of company, and its needs. For example, Cooper (2017) presents the socalled stage-gate system of NPD in three versions. The first version includes three phases, the second version consists of four phases, and the third version includes six phases. Furthermore, the process of creating new products has been assumed to be based on sequential phases, but in practice, this process is usually interactive and iterative.

The essence of the mentioned interactivity is the mutual interaction of the purpose of the conducted activity and the emerging trial structures, which are subsequent attempts to achieve the goal. The intention to create a new product on the basis of which it will be possible to gain a competitive advantage may be considered such a goal. Moreover, examples of trial structures in the development of new products include the concept of a new product, a prototype, trial production products, or the new product itself. Naturally, the goal affects the creation of the trial structure, but the reverse situation is also possible (when the trial structure affects the goal), due to limitations related to the achievement of the assumed goal. In the latter case, the planned goal may be modified; for example, the level of the planned competitive advantage may be changed.

In turn, the iterative nature of this process consists of finding the right solution by repeating the same actions many times using a feedback loop. For example, developing a new product concept on the basis of which a planned competitive advantage can be achieved may require such an approach. Then, the concept of a new product is first developed, and subsequently, the competitive advantage based on this concept is estimated. If it turns out that the considered concept of a new product does not allow a competitive advantage to be achieved, then, through a feedback loop, the concept is developed again and the competitive advantage is re-evaluated. If a satisfactory solution is reached, the iterative process can be completed; otherwise, the considered concept may be rejected.

The contribution of the work to the field of management is to propose a set of specific actions in the process of developing new products (presented in a concise manner in Table 1), which results from the intention to launch a new product on the market, which will enable a company to achieve a competitive advantage. To the best of our knowledge, this has so far been lacking in the professional literature. These specific actions have been defined for each phase of the NPD process. They are proposed under the assumption that the overriding goal of the development of new products is the intention to launch a new product that will allow a company to achieve a competitive advantage. Achieving this goal will make it possible to pursue other goals of the new product, such as obtaining a specific sales revenue target or a desired market share. Therefore, the specific actions identified in the work in the NPD process are important, and it is recommended that companies use them. This should reduce the risk of failure of the new product and facilitate the achievement of its planned results.

References

1. Barney, J. (2018). Why resource-based theory’s model of profit appropriation must incorporate a stakeholder perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 39(13), 3305–3325. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2949

2. Barney, J., & Hesterly, W. (2012). Strategic management and competitive advantage. Concept and cases (4th ed.). Pearson Education.

3. Brandenburger, A. M., & Stuart, H. W. (1996). Value-based business strategy. Journal of Economics and Management Strategy, 5(1), 5–24.

4. Cerda, A. A., & García, L. Y. (2021). Willingness to pay for a COVID-19 vaccine. Applied Health Economics and Health Policy, 19(3), 343–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40258021-00644-6

5. Cooper, R. G. (2017). Winning at new products. Creating value through innovation (5th ed.). Basic Books.

6. Cooper, R. G. (2018). Best practices and success drivers in new product development. In P. Golder, & D. Mitra (Eds.), Handbook on research on new product development (pp. 410–434). Edward Elgar Publishing.

7. Costa, L. A., Cool, K., & Dierickx, I. (2013). The competitive implications of the deployment of unique resources. Strategic Management Journal, 34, 445–463. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj

8. Crawford, M., & Di Benedetto, A. (2011). New products management (10th ed.). McGraw-Hill Irwin. https://doi.org/10.1016/0923-4748(93)90075-T

9. Dąbrowski, D. (2009). Informacje rynkowe w rozwoju nowych produktów. Seria Monografie, nr 93, Wydawnictwo Politechniki Gdańskiej.

10. Dąbrowski, D. (2010). Identyfikacja sposobności do tworzenia nowych produktów. In D. Dąbrowski (Ed.), Marketing. Rozwój działań (pp. 119–141). Katedra Marketingu, Wydział Zarządzania i Ekonomii, Politechnika Gdańska.

11. Dąbrowski, D. (2022a). Szacowanie przewagi konkurencyjnej w procesie rozwoju nowego produktu — ujęcie praktyczne. In P. Cabała, J. Walas-Trębacz, & T. Małkus (Eds.), Zarządzanie organizacjami w społeczeństwie informacyjnym. Strategie — projekty — procesy (pp. 67–78). Towarzyswo Naukowe Organizacji i Kierownictwa. Dom Organizatora.

12. Dąbrowski, D. (2022b). Wiedza rynkowa i twórczość w kształtowaniu nowych produktów. Wyd. Politechniki Gdańskiej.

13. Dhebar, A. (2016). Bringing new high-technology products to market: Six perils awaiting marketers. Business Horizons, 59(6), 713–722. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2016.08.006

14. Evanschitzky, H., Eisend, M., Calantone, R. J., & Jiang, Y. (2012). Success factors of product innovation: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 29(1994), 21–37. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5885.2012.00964.x

15. Garcia, R. (2014). Creating and marketing new products and services. CRC Press.

16. Gorynia, M. (2009). Teoretyczne aspekty konkurencyjności. In E. Łaźniewska, & M. Gorynia (Eds.), Kompendium wiedzy o konkurencyjności (pp. 48–66). WN PWN.

17. Henard, D. H., & Szymanski, D. M. (2001). Why some new products are more successful than others. Journal of Marketing Research, 38(3), 362–375. https://doi.org/10.1509/ jmkr.38.3.362.18861

18. Kaczmarczyk, S. (2016). Badania marketingowe wybranych elementów wyposażenia nowego produktu w cyklu innowacyjnym. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, 262, 80–95.

19. Kahn, K. B. (2001). Product planning essentials. Sage Publications.

20. Kahn, K. B. (2013). New product development glossary. In K. B. Kahn (Ed.), The PDMA handbook of new product development (3rd ed., pp. 435–476). John Wiley & Sons.

21. Kotler, P., Amstrong, G., & Opresnik, M. O. (2018). Principles of marketing (17th ed.). Pearson Education.

22. Lee, H., & Markham, S. K. (2016). PDMA comparative performance assessment study (CPAS): Methods and future research directions. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 33, 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpim.12358

23. Mantura, W. (2009). Znaczenie i ogólne zagadnienia konkurencyjności przedsiębiorstw.

In S. Lachiewicz, & M. Matejun (Eds.), Konkurencyjność jako determinanta rozwoju przedsiębiorstwa (pp. 21–30). Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej.

24. Nayak, B., Bhattacharyya, S. S., & Krishnamoorthy, B. (2022). Exploring the black box of competitive advantage — An integrated bibliometric and chronological literature review approach. Journal of Business Research, 139(March 2021), 964–982.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.10.047

25. Obłój, K. (2007). Pułapki teoretyczne zasobowej teorii organizacji. Przegląd Organizacji, 5, 7–10.

26. Peteraf, M., & Barney, J. (2003). Unraveling the resource based tangle. Manegerial and Decision Economics, 24, 309–323.

27. Porter, M. E. (1985). Competitive advantage. Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press.

28. Rutkowski, I. P. (2007). Rozwój nowego produktu. PWE.

29. Sojkin, B. (Ed.). (2003). Zarządzanie produktem. PWE.

30. Sopińska, A. (2009). Czynniki konkurencyjności polskich przedsiębiorstw. In S. Lachiewicz, & M. Matejun (Eds.), Konkurencyjność jako determinanta rozwoju przedsiębiorstwa (pp. 41–49). Wydawnictwo Politechniki Łódzkiej.

31. Sosnowska, A. (Ed.). (2003). Zarządzanie nowym produktem. Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH.

32. Waniowski, P. (2005). Badanie cen. In K. Mazurek-Łopacińska (Ed.), Badania marketingowe. Teoria i praktyka (pp. 370–396). WN PWN.

Dariusz Dąbrowski — is an Associate Professor at the Gdańsk University of Technology, Faculty of Management and Economics, Gdańsk, Poland. His scientific interests are focussed on problems related to product innovation management and the market orientation of organisations. His recent research revolves around issues concerning the attainment of competitive advantage through new products, creativity, the utilisation of market knowledge in new product development, and the implementation of market orientation and marketing programmes in the hotel industry. He has actively participated in numerous research projects conducted at academic centres and industry-driven initiatives.