- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Dynamika otoczenia – wpływ na przewagę konkurencyjną firmy usługowej z perspektywy dynamicznych zdolności CRM

Anetta Pukas*

Department of Marketing, Faculty of Management, Wroclaw University of Economics and Business,

Komandorska 118/120, 53-345 Wrocław, Poland

*E-mail: anetta.pukas@ue.wroc.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-6318-2516

Abstrakt:

Cel: Problemem niniejszego artykułu jest identyfikacja dynamiki otoczenia i wpływu na przewagę konkurencyjną firmy usługowej z perspektywy dynamicznych zdolności CRM. Podjęte badania literaturowe mają na celu opracowanie wielowymiarowej konceptualizacji dynamicznego otoczenia oraz zaproponowanie teoretycznego modelu do analizy wpływu dynamizmu otoczenia na związek pomiędzy dynamicznymi zdolnościami CRM a przewagą konkurencyjną.

Metodyka badań: W oparciu o perspektywę szkoły zasobowej (RBV) oraz koncepcję dynamicznych zdolności (DCV) zastosowano metodę krytycznej analizy literatury. Analizie poddano źródła literaturowe powstałe w ostatnich dwóch dekadach.

Wyniki badań/ustalenia: Wynikiem podjętych badań literaturowych stało się wypracowanie nowej konceptualizacji dynamicznego otoczenia i jego 3 istotnych wymiarów, a także propozycja konstruktów w modelu teoretycznym, w którym dynamika otoczenia odgrywa rolę moderującą w relacji między dynamicznymi zdolnościami CRM i przewagą konkurencyjną.

Implikacje/Rekomendacje: Jako implikacje dla dalszych badań należy wskazać empiryczną weryfikację stworzonego modelu oraz sprawdzenie zależności między konstruktami.

Wkład w rozwój dyscypliny: Ustalenia z badań poszerzają zastosowanie RBV i DCV w wiedzy marketingowej. Ponadto zaproponowany model i wnioski z tego badania skłaniają firmy usługowe do rozwijania zdolności CRM, które mogą usprawnić firmę, umożliwiając tym samym budowanie przewagi konkurencyjnej w dynamicznym otoczeniu.

MINIB, 2023, Vol. 49, Issue 3

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0017

Str. 101-122

Opublikowano 15 września 2023

Dynamika otoczenia – wpływ na przewagę konkurencyjną firmy usługowej z perspektywy dynamicznych zdolności CRM

Introduction

The proposal of the dynamic capabilities (DCs) paradigm as an extension of the resource-based view (RBV) has become a passionate area of academic research in strategic management and, in recent years, in marketing. However, an analysis of the literature shows that research on this concept in the body of marketing knowledge is still fragmented and scattered (Barrales-Molina et al., 2014). Research gaps continue to appear regarding the identification of the role and mechanism of the influence of marketing resources and capabilities on competitive advantage. Hence, it is becoming highly interesting for the development of science to adopt a dynamic perspective in the study of customer relationship management (CRM) as one of the marketing resources. There is an increase in the number of publications on this topic in the literature, but empirical research in the service business sector is very poorly represented.

With increasing competition and technological advances, firms face highly dynamic environments (Teng et al., 2022; Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2014). From the dynamic capabilities view (DCV) perspective, firms with the capabilities that can extend, modify, change and create business capabilities in response to environmental dynamism play a fundamental role on the market.

In terms of assumptions, the concept of DCs is described as a response to the modern, rapidly changing environment. The consequence is the conclusion, but most often at the conceptual level, that the high dynamism of the business environment and market changes justifies enterprises’ use of DCs and dynamic perspectives in scientific research. However, this guideline is not yet supported by sufficient empirical evidence. Thus, there is an exploratory gap. First of all, the impact of the dynamism of the environment on the effect of the company’s DCs remains insufficiently researched empirically (Barrales-Molina et al., 2014; Barreto, 2010; Wang & Ahmed, 2007).

In today’s hyper-competitive environment, companies’ understanding of the dynamics of the environment and its role in creating competitive advantage is crucial. There is a growing body of literature on this topic, but empirical research in the service business sector is very poorly represented. Therefore, the central premise for taking up the topic of this paper is the speed of changes in the market environment observed in recent years and the need to determine these changes in the functioning of enterprises. This is especially true about the service sector, which is very sensitive to changes in competition processes. Still, the concept of turbulence or dynamism is ambiguous. There is a considerable lack of clarity and virtually no agreement on the exact meaning of environmental turbulence. This confusion reflects the diversity of orientations in studying organisational environments and the divergent approaches developed to measure it. There is an emerging need for a new conceptualisation of the environment’s dynamism. Responding to such demand, this work aims to develop a multidimensional conceptualisation of the dynamic environment and propose a theoretical model for analysing the impact of the environment’s dynamism on the relationship between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage.

To achieve the purpose of the article, the method of critical literature analysis was used. Literature sources written in the last two decades were analysed. This is because during this period, the emergence of significant changes in the global environment and even economic crises could be observed. In addition, earlier publications key to the researched subject were also used. The resources of EBSCO, SCOPUS and Web of Science databases were used for the analysis (keywords relevant to the topic of the article were used, i.e. 'dynamic CRM capabilities’, 'competitive advantage’, 'dynamic environment’ and 'turbulent environment’). About 60 articles were analysed. As a result of the literature review, a conceptualisation of the dynamism of the environment taking into account three of its main dimensions, namely variability, complexity and predictability, was created. The second result is the proposal of constructs and the theoretical model in which the dynamic environment is the moderating variable of the relationship between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage.

CRM DCs and Competitive Advantage — the Literature Framework

The research perspective related to the resource school trend (resourcebased view) and the DC approach allows today to consider and verify CRM as a set of resources and capabilities also with dynamic characteristics. Literature sources indicate that developing excellent CRM skills-creating close relationships with customers-and managing them-is one of the most important sources of the highest business performance in today’s competitive business environment (Day, 2014; Kale, 2004).

CRM capabilities are much more challenging to understand and emulate than other enterprise capabilities because their development takes time and relies on a complex interplay of resources, tacit knowledge and interpersonal skills (Hooley et al., 2005). In addition, building stronger customer relationships provides a foundation for understanding changing customer requirements and identifying the most appropriate ways to meet customer needs vis-a-vis those used by competitors, which may provide more significant opportunities for better business results (Day, 2014). However, these opinions contained in many articles based on different research perspectives are not always sufficiently confirmed in the empirical layer. In addition, based on the marketing literature, it can be noted that most studies focus on the impact of CRM on customers and the creation of customer value such as customer loyalty or satisfaction (Mithas et al., 2005; Yim et al., 2004), which then lead to increased company profitability (Cao & Gruca, 2005). CRM capabilities are included in the group of enterprise marketing capabilities. Still, their conceptualisation in the literature is very ambiguous, meaning that there is no consistent and generally accepted definition and structure of CRM capabilities (Table 1).

The issues of the complicated and complex conceptualisation of CRM capabilities, taken up in the studies of Day (2000) or Coltman et al. (2009) and other authors, made it possible to attempt to use the concept of DCs in CRM research. High importance, with the character of a breakthrough, can be attributed to the 2009 publication Dynamic capabilities: the missing link in CRM investments by Maklan and Knox, in which the authors point to the dynamic approach as necessary for use in the study of CRM capabilities, as well as in the practical dimensions of using this knowledge. Despite the rise in popularity of the dynamic perspective in the field of management science, including marketing, although perhaps to a lesser extent, the growth in the number of publications on the use of the dynamic perspective (DC) in CRM research over the past decade has not been significant.

Previous literature on CRM research has emphasised such topics as the critical role of organisational culture (Bohling et al., 2006; Kale, 2004), organisational alignment (Boulding et al., 2005; Roberts et al., 2005), the appropriate use of customer lifetime value analysis (Reinartz & Kumar, 2002; Ryals, 2005; Venkatesan & Kumar, 2004) or motivating employees to improve customer management (Bohling et al., 2006; Zablah et al., 2004). On the other hand, a content analysis of the literature identifying the main DCs in marketing indicated that CRM is becoming an integral component of a set of DCs consisting of (Maklan & Knox, 2009):

1. Demand management-generating revenue for goods and services;

2. Marketing knowledge creation-generating and disseminating companywide insights into consumers, markets, competitors, environmental trends, distributors, alliance partners and online communities;

3. Building brands-creating and maintaining brands for products, services and organisations;

4. CRM-developing how the company relates to consumers.

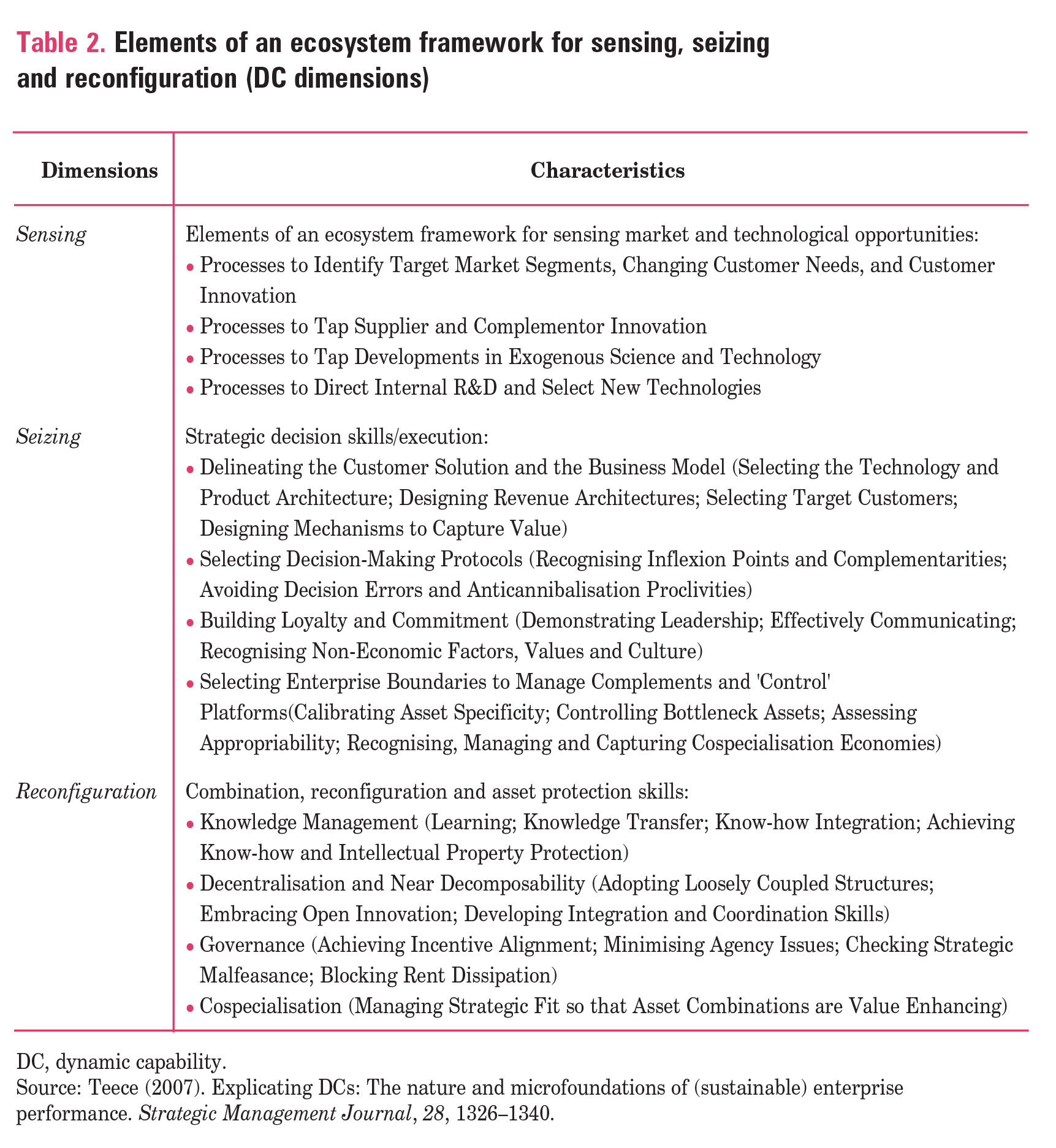

An analysis of the literature also indicated that researchers had identified dimensions characteristic of DCs (e.g. Baretto, 2010; Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Jantunen et al., 2012; Teece, 2018; Teece et al., 1997, 2016; Wang & Ahmed, 2007). Teece et al. (2016) interpret these dimensions as interdependent components that constitute DCs. Therefore, 'sensing’ opportunities, 'seizing’, which is the exploitation of emerging opportunities, and 'transforming/reconfiguration’ related to resource configuration and reconfiguration are essential if a company is to sustain itself in the market in the long term. DCs can enable a company to enrich its ordinary capabilities and use them, and those of its partners, to pursue ventures that yield positive results (Teece, 2007). This is due to changes in customers, competition and technology.

Teece (2007, 2016) provided an interpretation of the dimensions of DCs by identifying a four-element structure for each dimension (Table 2).

Bratnicka-Myśliwiec et al. (2019) also described a set of processes, elements and variables of DCs. They identified the following elements of DCs: entrepreneurial orientation (referring to opportunity sensing), value creation (based on opportunity seizing or pursuit, effectuation, bricolage and stakeholder synergy) and resource reconfiguration as the core of DCs.

Referring to CRM DCs, it can be said that the dimensions of these capabilities are embedded in CRM activities and organisational processes and reflect the company’s skills and accumulated knowledge to identify attractive customers and potential customers, initiate and maintain relationships with attractive customers, and intensify profitable relationships at the customer level (Morgan et al., 2009). In Teece (2007, 2018) stated perspective, however, they are scattered and can be found in several of the stated components of an organisation’s DCs. It should be noted that while it is easy to list CRM activities based on such and similar descriptors, it is difficult to determine whether they are dynamic (whether they are DCs), much less what the degree of dynamism is. Lacking in the existing literature is a detailed identification of which CRM activities can be considered, for example, as CRM market opportunity detection capabilities, which are related to CRM capabilities for exploiting emerging CRM opportunities, and which are responsible for reconfiguring CRM resources.

According to Day (2000), strong customer relationship capabilities are the essential marketing capabilities that enable companies to leverage related customer relationship resources to build sustainable competitive advantages. In an attempt to classify all definitions of competitive advantage, Sigalas and Pekka-Economou (2013) identified two definitional streams regarding the conceptual delineation of competitive advantage. The first stream defines competitive advantage in terms of an organisation’s performance/results, such as high relative profitability, above-average profits, the gap between benefits and costs, superior financial performance, and economic profits. The second stream defines competitive advantage by referring to its sources or determinants, for example specific characteristics of particular product markets, cost leadership, differentiation, locations, technologies, product features and a set of specific, idiosyncratic resources and capabilities of the company (Sigalas & Pekka-Economou, 2013).

In the discourse of management science, defining the type of competitive advantage boils down to stating what the superiority of a given enterprise over others is, expressed in market performance (Haffer, 2012). The second important feature to describe the advantage is its size, which can be understood as a difference in parameters describing various activities, processes and behaviours in the enterprise and competitors. In the literature, you can also find a statement that the measure of the advantage’s size is the organisation’s competitive position. The third important dimension of competitive advantage is durability, which is not directly related to its duration, but concerns the possibility of copying it (Barney, 1991).

Considering the theoretical basis and the analysis of empirical studies, it can be concluded that competitive advantage is a multidimensional concept. The multifactorial of this construct should be considered both as the quantitative dimension in the form of financial performance and the qualitative measurement in the form of strategic effects (Hemmati et al., 2016). In conclusion, following Teece (2007), the DC research paradigm, particularly in the field of CRM, is still relatively new. At the same time, it should be recognised that the dynamic approach is a very expansive and valuable research direction, providing many opportunities for researchers and business practitioners to fully understand the links between managerial actions in the organisation, CRM capabilities, and the long or short-term competitive advantage of the company. Therefore, there is a need for further research in this area of both conceptual and empirical nature.

The Dynamism of Environment — Conceptualisation for the Service Industry

The concept of DCs, according to its authors Teece, Pisano and Shuen, assumes that the competitive advantage of an organisation results from DCs, which are understood as the ability to adjust, integrate and reconfigure internal and external resources and competencies in reaction to the rapidly changing environment. However, other researchers believe DCs may be less effective in highly dynamic environments. According to Eisenhardt and Martin (2000), DCs cannot constitute a source of competitive advantage in a high-speed environment, that is to say precisely in the conditions in which Teece et al. (1997) see the need for dynamic abilities as the best.

With increasing competition and technological advances, firms face highly dynamic environments (Van Vaerenbergh et al., 2014). From the DCV perspective, firms with the capabilities that can extend, modify, change and create business capabilities in response to environmental dynamism play a fundamental role in changing operational routines and in ensuring that the firm can change its overall operations and have new sets of decision options (Keiningham et al., 2014).

The service sector is growing rapidly around the world, contributing significantly to the growth of the global economy (Menguc et al., 2017). Therefore, the importance of identifying sources and ways of achieving a competitive advantage in this sector is increasing. Today, organisations depend on delivering exceptional service quality to attract and retain loyal customers (Kasiri et al., 2017; Malhotra et al., 2020). The changing external environment and increasing conditions of volatility, uncertainty, complexity and ambiguity (Petricevic & Teece, 2019) raise the question: How do service companies develop resilience to such dynamic changes? The answer can be to use the DCs approach.

The time of COVID-19 pandemic negatively affected many sectors of the global economy, including the process of providing services, especially such as hospitality, transportation, tourism and cultural services. However, this time of change also fostered new opportunities and patterns in business management transforming, for example, corporate culture into a 'home culture’ (Couch et al., 2021). On the other hand, the Industry 4.0 revolution has influenced the implementation of new business practices, shifting them towards digitisation. To survive and thrive in dynamically changing crisis conditions such as a pandemic or warfare, it is necessary to move away from traditional management approaches.

Research on changes in the business environment has been conducted for years. As early as 1983 Miller and Friesen wrote that 'the dynamism of the environment refers to the amount and unpredictability of changes in customer tastes, production or service technology, and modes of competition in a company’s major industries’ (Miller & Friesen, 1983, p. 233).

Emerging research in the past conceptualised the term 'turbulent environment’ as describing changes in it (Baburoglu, 1988; Khandwalla, 1977; Volberda & van Bruggen, 1997). However, in recent years, researchers have more often used the term 'dynamic environment’ (Agyapong et al., 2020; Tajeddini & Mueller, 2019; Teng et al., 2022; Visser & Sheepers, 2020; Wang et al., 2021), or even environmental velocity (McCarthy et al., 2010). Contemporary authors even use these terms interchangeably.

Changes in the organisation’s environment have been defined in various ways and concern several potentially important dimensions (Table 3). The environment’s dynamism can be described in terms of the frequency, magnitude and irregularity of changes in factors such as competition, customer preferences, and technology (McCarthy et al., 2010; Miller & Friesen, 1983).

Still, the concept of turbulence or dynamism is ambiguous. There is a considerable lack of clarity and virtually no agreement on the exact meaning of environmental turbulence. This confusion reflects the diversity of orientations in studying organisational environments and the divergent approaches developed to measure it. There is an emerging need for a new conceptualisation of the environment’s dynamism. Responding to such demand, the present author developed a multidimensional conceptualisation of the dynamic environment and proposed a theoretical model for analysing the impact of the environment’s dynamism on the relationship between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage.

Based on the influential concept of Miller and Friesen (1983), it is possible to identify the essential characteristics of the dynamism of the environment, which the authors see as volatility (speed and amount of change) and unpredictability (uncertainty) (Schilke, 2014). For example, industry structure changes, market demand instability and the likelihood of rapid changes in the environment are essential elements of these dynamics (e.g. Jansen et al., 2006; Wilhelm et al., 2015). Accordingly, an environment characterised by low dynamics exhibits infrequent changes, and market participants usually anticipate these changes. In contrast, a highly dynamic environment is one in which rapid and discontinuous changes are expected. Regular changes occur along predictable and linear paths in a moderately dynamic environment.

According to other authors, a turbulent/dynamic environment is an unpredictable, expanding, changing environment; it is an environment in which components are marked by change, an environment with a high degree of interconnectedness with the organisation (Baum & Wally, 2003; Emery & Trist, 1965; Khandwalla, 1977; Volberda & van Brugen, 1997). Baburoglu (1988) supports this view of increased complexity, significant uncertainty, and dynamic and unexpected directionality of events but particularly emphasises the transitional state of turbulent environments. This discussion of environmental dynamism clearly shows that turbulence is a complex aggregate of different dimensions related to change and that some dimensions are more independent than others. Using the existing body of work to achieve the purpose of this article, the author proposed his own set of three most valuable dimensions for assessing the dynamism of the environment of service companies. These are variability, complexity and predictability. These three sub-dimensions seem crucial at this stage of the theory’s development.

In this new conceptualisation of environmental dynamism, variability as a sub-dimension describes the degree to which the components of an organisational unit’s environment remain essentially the same over time or are constantly changing. For example, in the environment, we can observe changes in technology, customer preferences, fluctuations in demand for products and services, or competitors’ constant withdrawal or emergence. Hence, in this dimension, it is crucial to determine the rate of environmental change (frequency) and the intensity of changes. In addition to the variability in the environment’s dynamism, it is crucial to determine the complexity of the domain. Based on previous studies that consider the number of elements involved in a given environmental component, it can be concluded that the greater the number of factors involved, the more complex the environment. However, other theorists study the number of elements and, perhaps even more importantly, the interdependence of these elements, contributing to a complete analysis of environmental complexity. Such a combination should be considered a target for a new conceptualisation for the services industry. Another third dimension of environmental dynamism is predictability. It has definitely received the most attention in research on organisational environments (eg. Duncan, 1972; Eppink, 1978; Krijnen, 1979; Lawrence & Lorsch, 1967; Volberda & van Brugen, 1997). When the transformations within the elements of the environment are linear, cyclical, or both linear and cyclical, management can extrapolate future changes and prepare for future developments. As an example, consider seasonality in demand patterns in tourism or hospitality. It is also extremely important to determine the availability of information about environmental changes. Some organisations operate in environments where such data are not available. In such fundamentally unpredictable environments, management must be highly flexible.

Thus, in new conceptualisation of environmental dynamism, the predictability of change is a sub-dimension that the availability of information about the change has supplemented.

The Moderating Role of the Environmental Dynamism

in CRM DCs and Competitive Advantage Relation

— the Theoretical Model for Services Company

The specificity of a classic service as a market offer and its process nature, largely related to the physical presence of the service provider and dependent on the client’s involvement, makes this sector of the economy very sensitive to changes in the market environment. At the same time, the currently observed development of IT technology and the global problems resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic resulted in the need to provide many services virtually or even gave an impulse to the emergence of completely new service offers, which allowed many companies in this industry to maintain or strengthen their competitive advantage.

The response of the scientific world to today’s rapidly changing environment seems to be precisely the concept of DCs, since its assumptions allow to perceive and use DCs as creating favourable conditions for companies to respond to opportunities and threats in the business environment. This seems particularly relevant in the context of building long-term customer relationships as a competitive potential for service sector companies as well. This is because, as the considerations in the earlier subsections indicated, it is important for empirical research to pay more attention to the structure and role of the dynamism of the environment, as a potentially important moderating variable in the relationship between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage. This will enhance the value and relevance of future research. Companies operating in a highly dynamic environment face the challenge of adapting, renewing and reconfiguring their resources to adequately respond to changing conditions (Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011; Teece et al., 1997). This is also the assumption underlying the concept of DCs. A few studies suggest that DCs cause different effects on the results of companies operating in conditions of high and low dynamics of the environment (Wilhelm et al., 2015). Thus, the relationship is not as linear as theoretical concepts assumed.

In the literature, there are two competing views on the influence of the environment’s dynamism on the relationship between the DCs and the competitive advantage of the company, with little integration of both perspectives (Schilke, 2014). The first view suggests that there must be an extremely important (critical) situation in the company to obtain significant value from the introduced changes in the organisation’s capabilities (Drnevich & Kriauciunas, 2011; Helfat et al., 2007; Winter, 2003; Zahra et al., 2006; Zollo & Winter, 2002). This is because building and using DCs is expensive. These costs typically result from various activities related to developing new resources, reconfiguring existing resources and combinations thereof. In addition, costs may increase if the continuous reconfiguration of resources unnecessarily disrupts existing activities (Schilke, 2014).

The second group of researchers emphasises that DCs based on routines are not always sufficient to effect change, even when there is a significant need for resource configuration (Eisenhardt & Martin, 2000; Schreyögg & Kliesch-Eberl, 2007). History-based organisational change is usually very effective in limiting the company’s adjustment. Experiential learning research shows that this type of organisational change can be problematic when previously unknown factors alter the basis of a competitive company’s success, as is the case in highly dynamic environmental conditions (Levinthal & Rerup, 2006; March & Levinthal, 1993; Schilke, 2014).

Based on the literature review and its critical analysis, the author identified the theoretical foundations that form the conceptual framework of the theoretical model. The decomposition (conceptualisation) of constructs in the proposed model was based on the assumptions of the resource-based school (RBV) and the dynamic approach (DC) and the evolutionary theory of competitive advantage. Figure 1 illustrates the conceptual model of the relationships between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage and shows the moderating role of environmental dynamism.

Conclusions

In today’s market environment, global competition is emerging alongside the local competition. Changes in the organisation’s environment are progressing at an ever-increasing pace. In some industries, changes occur by leaps and bounds, while in others, they occur smoothly. This means that maintaining a sustainable, long-term competitive advantage sometimes becomes impossible. According to researchers today, an organisation’s sustainable competitive advantage comes from creating short-term competitive advantages. This implies the possibility, and even the necessity, of adopting a dynamic approach.

In this regard, researchers continue the discussion on the problems of the impact of DCs on the economic and market effects of the company. However, to a small extent, they still focus their empirical research on identifying the characteristics, level of dynamism, and variability of elements of the environment that can be considered definite for optimising the use of the capabilities possessed by the company also in the field of CRM.

The primary goal of the present study was to develop a multidimensional conceptualisation of the dynamic environment. The result of the literature research undertaken in this study became the development of new dimensions of the dynamic environment. In this approach, variability, complexity and predictability, as the sub-dimensions, seem crucial at this stage of the theory’s development.

The second goal of this paper was the proposal of constructs in the theoretical model, where the dynamism of the environment plays a moderating role in the relationship between dynamic CRM capabilities and competitive advantage. It has been argued that more research on dynamic company environment is needed to find the source of long competitive advantage. As implications for further research, empirical verification of the created model and verification of the relationship between the constructs should be indicated.

References

1. Agyapong, A., Zamore, S., & Mensah, H. K. (2020). Strategy and performance: Does environmental dynamism matter? Journal of African Business, 21(3), 315–337. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228916.2019.1641304

2. Baburoglu, O. N. (1988). The Vortical Environment: The Fifth in the Emery-Trist Levels of Organizational Environments, Human Relations, 41(3), 181–210. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/001872678804100301

3. Barney, J. B. (1991). Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17(1), 99–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639101700108

4. Barrales-Molina, V., Martínez-Lopez, F. J., & Gázquez-Abad, J. C. (2014). Dynamic marketing capabilities: Toward an integrative framework. International Journal of Management Reviews, 16(4), 397–416. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12026

5. Barreto, I. (2010). Dynamic capabilities: A review of past research and an agenda for the future. Journal of Management, 36(1), 256–280. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206309350776

6. Baum, J.R., & Wally, S. (2003). Strategic Decision Speed and Firm Performance. Strategic Management Journal, 24, 1107–1129. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.343

7. Bohling, T., Bowman, D., LaValle, S., Mittal, V., Narayandas, D., Ramani, G., & Varadarajan, R. (2006). CRM implementation: Effectiveness issues and insights. Journal of Service Research, 9(2), 184–194. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094670506293573

8. Boulding, W., Staelin, R., Ehret, M., & Johnston, W. J. (2005). A Customer Relationship Management roadmap: What is known, potential pitfalls, and where to go, Journal of Marketing, 69(4), 155–166. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.1

9. Bratnicka-Myśliwiec, K., Dyduch, W., & Bratnicki, M. (2019). Theoretical foundations of dynamic capabilities measurement: A multi-logic approach. Przegląd Organizacji, 12, 4–13. https://doi.org/10.33141/po.2019.12.01

10. Buttle, F. A. (2001). The CRM value chain, Marketing Business, February, 52–55.

11. Cao, Y., & Gruca, T. S. (2005). Reducing adverse selection through customer relationship management. Journal of Marketing, 69, 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.219

12. Coltman, T. R., Devinney, T. M., & Midgley, D. F. (2009). Customer Relationship Management and Firm Performance, INSEAD Working Paper Series, 18, 1–37. https://doi.org/ 10.2139/ssrn.1386484

13. Couch, D. L., O’Sullivan, B., & Malatzky, C. (2021). What COVID-19 could mean for the future of „work from home”: The provocations of three women in the academy. Gender, Work & Organization, 28, 266–275. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12548

14. Day, G. S. (2000). Capabilities for forging customer relationships. Marketing Science Institute, Cambridge.

15. Day, G. S. (2014). An outside-in approach to resource-based theories. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 42(1), 27–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-013-0348-3

16. Day, G.S., & Van den Bulte, C. (2002) Superiority in Customer Relationship Management: Consequences for Competitive Advantage and Performance. The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania.Dess, G.G., & Beard, D.W. (1984) Dimensions of Organizational Task Environments. Administrative Science Quarterly, 29, 52–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393080

17. Drnevich, P. L., & Kriauciunas, A. P. (2011). Clarifying the conditions and limits of the contributions of ordinary and dynamic capabilities to relative firm performance. Strategic Management Journal, 32(11), 254–279. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.882

18. Duncan, R. B. (1972). Characteristics of organizational environments and perceived environmental uncertainty. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(3), 313–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392145

19. Eisenhardt, K. M., & Tabrizi, B. N. (1995). Accelerating Adaptive Processes: Product Innovation in the Global Computer Industry. Administrative Science Quarterly, 40, 84–110. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2393701

20. Eisenhardt, K. M., & Martin, J. A. (2000). Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21, 1105–1121. https://doi.org/10.1002/10970266(200010/11)21:10/11<1105::AID-SMJ133>3.0.CO;2-E

21. Emery, F. E., & Trist, E. L. (1965). The causal texture of organizational environments. Human Relations, 18(1), 21–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872676501800103

22. Eppink, D. J. (1978). Planning for Strategic Flexibility, Long Range Planning, 11, 9–18.

23. Haffer, R. (2012). Systemy pomiaru wyników działalności polskich przedsiębiorstw i ich wpływ na osiągane wyniki, Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu, 265, 156–171.

24. Helfat, C. E., Finkelstein, S., Mitchell, W., Peteraf, M. A., Singh, H., & Winter, S. G. (2007). Dynamic Capabilities: Understanding strategic change in organizations, Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

25. Hemmati, M., Feiz, D., Jalilvand, M. R., & Kholghi, I. (2016). Development of fuzzy twostage DEA model for competitive advantage based on RBV and strategic agility as a dynamic capability. Journal of Modelling in Management, 11(1), 288–308. https://doi.org/10.1108/JM2-12-2013-0067

26. Hooley, G. J., Greenley, G. E., Cadogan, J. W., & Fahy, J. (2005). The performance impact of marketing resources. Journal of Business Research, 58(1), 18–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0148-2963(03)00109-7

27. Jansen, J. J. P., Van Den Bosch, F. A. J., & Volberda, H. W. (2006). Exploratory Innovation, Exploitative Innovation, and Performance: Effects of Organizational Antecedents and Environmental Moderators. Management Science, 52, 1661– 1674. http://dx.doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.1060.0576

28. Jantunen, A., Ellonen, H. K., & Johansson, A. (2012). Beyond appearances — Do dynamic capabilities of innovative firms actually differ? European Management Journal, 30(2), 141–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2011.10.005

29. Kale, S. (2004). CRM failure and the seven deadly sins. Marketing Management, 13(5), 42–47.

30. Kasiri, L. A., Guan Cheng, K. T., Sambasivan, M., & Sidin, S. M. (2017). Integration of standardization and customization: Impact on service quality, customer satisfaction, and loyalty. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 35, 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jretconser.2016.11.007

31. Keiningham, T. L., Aksoy, L., Malthouse, E. C., Lariviere, B., & Buoye, A. (2014). The cumulative effect of satisfaction with discrete transactions on share of wallet. Journal of Service Management, 25(3), 310–333. https://doi.org/10.1108/JOSM-08-2012-0163

32. Khandwalla, P. N. (1977). The Design of Organizations. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, New York.

33. Lawrence, P. R. & Lorsch, J. W. (1967). Organization and Environment: Managing Differentiation and Integration. Irwin, Homewood.

34. Krijnen, H. G. (1979). The flexible firm, Long Range Planning, 12(2), 63–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(79)90074-8

35. Levinthal, D., & Rerup, C. (2006). Crossing an apparent chasm: bridging mindful and less-mindful perspectives on organizational learning, Organization Science, 17(4), 502–513. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1060.0197

36. Lin, R. J., Chen, R. H., & Chiu, K. K. S. (2010). Customer relationship management and innovation capability: an empirical study, Industrial Management and Data Systems, 110(1), 111–133.

37. Liu, H. (2007). Development of a framework for customer relationship management (CRM) in the banking industry. International Journal of Management, 24(1), 15–32.

38. Maklan, S., & Knox, S. (2009). Dynamic capabilities: The missing link in CRM investments. European Journal of Marketing, 43(11/12), 1392–1410. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/03090560910989957

39. March, J. G., & Levinthal, D. A. (1993). The myopia of learning. Strategic Management Journal, 14(S2), 95–112. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250141009

40. McCarthy, I. P., Lawrence, T. B., Wixted, B., & Gordon, B. R. (2010). A multidimensional conceptualization of environmental velocity. Academy of Management Review, 35(4), 604–626. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.4.zok604

41. Menguc, B., Auh, S., Yeniaras, V., & Katsikeas, C. S. (2017). The role of climate: Implications for service employee engagement and customer service performance. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 45, 428–451. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11747-017-0526-9

42. Miller, D., & Friesen, P. H. (1983). Strategy-making and environment: The third link. Strategic Management Journal, 4(3), 221–235.

43. Mithas, S., Krishnan, M. S., & Fornell, C. (2005). Why do customer relationship management applications affect customer satisfaction? Journal of Marketing, 69, 201–209. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.201

44. Morgan, N. A., Slotegraaf, R. J., & Vorhies, D. W. (2009). Linking marketing capabilities with profit growth. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 26(4), 284–293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijresmar.2009.06.005

45. Petricevic, O., & Teece, D. J. (2019). The structural reshaping of globalization: Implications for strategic sectors, profiting from innovation, and the multinational enterprise. Journal of International Business Studies, 50, 1487–1512. https://doi.org/ 10.1057/s41267-019-00269-x

46. Reinartz, W., & Kumar, V. (2002). The mismanagement of customer loyalty. Harvard Business Review, 80(7), 86–94.

47. Roberts, M., Liu, R., & Hazard, K. (2005). Strategy, technology and organisational alignment: Key components of CRM success, Journal of Database Marketing & Customer Strategy Management, 12(4), 315–326. http://dx.doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.dbm.3240268

48. Ryals, L. (2005). Making customer relationship management work: The measurement and profitable management of customer relationships. Journal of Marketing, 69, 252–261. http://dx.doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.2005.69.4.252

49. Saelee, R., Jhundrain P., & Muenthaisong, K. (2015). A conceptual framework of Customer Relationship Management Capability and marketing survival, Proceedings of the Academy of Marketing Studies, 19(2), 94–105.

50. Schilke, O. (2014). On the contingent value of dynamic capabilities for competitive advantage: The nonlinear moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Strategic Management Journal, 35, 179–203. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2099

51. Schreyögg, G., & Kliesch-Eberl, M. (2007). How dynamic can organizational capabilities be? Towards a dual-process model of capability dynamization. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 913–933. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.613

52. Sigalas, C., & Pekka-Economou, V. (2013). Revisiting the concept of competitive advantage: Problems and fallacies arising from its conceptualization. Journal of Strategy and Management, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.1108/17554251311296567

53. Tajeddini, K., & Mueller, S. (2019). Moderating effect of environmental dynamism on the relationship between a firm’s entrepreneurial orientation and financial performance. Entrepreneurship Research Journal, 9(4), 20180283. https://doi.org/10.1515/erj-2018-0283

54. Teece, D. J. (2007). Explicating dynamic capabilities: The nature and microfoundations of (sustainable) enterprise performance. Strategic Management Journal, 28, 1319–1350. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.640

55. Teece, D. J. (2018). Business models and dynamic capabilities. Long Range Planning, 51, 40–49.

56. Teece, D., Peteraf, M., & Leih, S. (2016). Dynamic capabilities and organizational agility: Risk, uncertainty, and strategy in the innovation economy. California Management Review, 58(4), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2016.58.4.13

57. Teece, D. J., Pisano, G., & Shuen, A. (1997). Dynamic capabilities and strategic management. Strategic Management Journal, 18(7), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1002/ (SICI)1097-0266(199708)18:7<509::AID-SMJ882>3.0.CO;2-Z

58. Teng, T., Tsinopoulos, C., & Kei Tse, Y. (2022). IS capabilities, supply chain collaboration and quality performance in services: The moderating effect of environmental dynamism. Industrial Management & Data Systems, 122(7), 1592–1619. https://doi.org/10.1108/IMDS-08-2021-0496

59. Van Vaerenbergh, Y., Orsingher, C., Vermeir, I., & Lariviere, B. (2014). A meta-analysis of relationships linking service failure attributions to customer outcomes. Journal of Service Research, 17(4), 381–398. https://doi.org/10.1177/10946705145383

60. Venkatesan, R., & Kumar, V. (2004). A customer lifetime value framework for customer selection and resource allocation strategy. Journal of Marketing, 68(4), 106–125. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.68.4.106.42728

61. Visser, J. D., & Scheepers, C. D. (2020). Exploratory and exploitative innovation influenced by contextual leadership, environmental dynamism and innovation climate. European Business Review, 34(1), 127–152. https://doi.org/10.1108/EBR-07-2020-0180

62. Volberda, H. W., & van Bruggen, G. H. (1997). Environmental turbulence: A Look into its dimensionality. NOBO Nederlandse Organisatie voor Bedrijfskundig Onderzoek, ERIM (Electronic) Books and Chapters. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1765/6438

63. Wang, C. L., & Ahmed, P. K. (2007). Dynamic capabilities: A review and research agenda. The International Journal of Management Reviews, 9(1), 31–51. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1468-2370.2007.00201.x

64. Wang, X., Sun, J., Tian, L., Guo, W., & Gu, T. (2021). Environmental dynamism and cooperative innovation: The moderating role of state ownership and institutional development. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 46, 1344–1375. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10961-020-09822-5

65. Wilhelm, H., Schlömer, M., & Maure, R. I. (2015). How Dynamic Capabilities affect the effectiveness and efficiency of operating routines under high and low levels of environmental dynamism. British Journal of Management, 26, 327–345. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1467-8551.12085

66. Winter, S. (2003). Understanding dynamic capabilities, Strategic Management Journal, 24(10), 991–995. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.318

67. Yim, F. H. -K., Anderson, R. E., & Swaminathan, S. (2004). Customer relationship management: Its dimensions and effect on customer outcomes. The Journal of Personal Selling and Sales Management, 24(4), 263–278.

68. Zablah, A. R., Bellenger, D. N., & Johnston, W. J. (2004). An evaluation of divergent perspectives on customer relationship management: Towards a common understanding of an emerging phenomenon. Industrial Marketing Management, 33(6), 475–489. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.indmarman.2004.01.006

69. Zahra, S. A., Sapienza, H. J., & Davidsson, P. (2006). Entrepreneurship and dynamic capabilities: A review, model and research agenda. Journal of Management Studies, 43(4), 917–955. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2006.00616.x

70. Zollo, M., & Winter, S. G. (2002). Deliberate learning and the evolution of dynamic capabilities, Organization Science, 13, 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1287/ orsc.13.3.339.2780

Anetta Pukas — Associate Professor of Management at Wroclaw University of Economics and Business. She is a scientist, researcher, and lecturer in the Department of Marketing. Her work and projects focus specifically on Customer Relationship Management, Services Marketing, and Dynamic Marketing Capabilities. The Author of the papers and books and a member of the European Marketing Academy (EMAC) and Polish Scientific Marketing Society.