- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Czy nazwa ma znaczenie? Sposoby komunikowania agencji public relations z otoczeniem na podstawie kwantytatywno-korpusowych badań nad językiem

Dariusz Tworzydło1*, Karina Stasiuk-Krajewska2, Przemysław Szuba3

1Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies, University of Warsaw, Poland

2SWPS University, Poland

3Faculty of Economics in Opole, The WSB University in Wroclaw, Wroclaw, Poland Poland

1*E-mail: dariusz@tworzydlo.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-6396-6927

2E-mail: kstasiuk-krajewska@swps.edu.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-8261-7335

3E-mail: przemyslaw.szuba@opole.merito.pl

ORCID: 0000-0002-7533-7818

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0001

Abstrakt:

W artkule zostały zaprezentowane wyniki badań przeprowadzonych za pomocą kwantytatywno-korpusowej analizy dyskursu (CADS) w oparciu o teorię konstruktywizmu społecznego oraz językowego obrazu świata (JOS). Badane były dwa korpusy tekstowe, zbudowane z dostępnych tekstów autoprezentacyjnych zamieszczonych na 415 stronach internetowych agencji PR w Polsce (są to największe tego typu badania w kraju). Korpus K1, w którym nazwa agencji jest ukierunkowana bezpośrednio na obszar komunikacji/PR i korpus K2—gdzie nie ma takiego powiązania w nazwie firmy. W toku analiz autorzy koncentrują się na rekonstrukcji samoopisu i autoprezentacji agencji (frekwencyjność i przekrój przez strukturę leksykalną korpusów) w kontekście profilu komunikacyjnego i demograficznego badanych agencji public relations. Analiza leksykalna korpusów pozwoliła także zidentyfikować elementy, które—w oczach praktyków rynku—uznawane są za istotne dla profesjonalnego public relations, a tym samym stanowią podstawę tożsamości profesjonalnej branży PR.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 51, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0001

Str. 1-20

Opublikowano 29 marca 2024

Czy nazwa ma znaczenie? Sposoby komunikowania agencji public relations z otoczeniem na podstawie kwantytatywno-korpusowych badań nad językiem

Introduction

This article is closely related to the continuation of the research project ‘Market analysis of PR agency services’ relevant to the pioneering and nationwide study of the entire public relations (PR) agency sector in our country. The project is conducted by Exacto’s research team in cooperation with the Faculty of Journalism, Information and Bibliology at University of Warsaw, Maria Sklodowska-Curie University in Lublin, and the Association of Public Relations Agencies. In the first part of the project (from November 2020 to July 2021), we have prepared a research operative that provides the opportunity for further analysis of the different methodological approaches.

The 934-entity operative was based on the compilation of the many available data sources along with their cross-checking and processing. During the desk research work, ‘a categorization key dedicated to the agency database was developed, which made it possible to systematize knowledge about the PR agency market in Poland. The survey was population-based among all PR agencies in Poland, and one of its results was the preparation of the country’s first complete list of such entities based on the definition criteria developed’ (Tworzydło & Szuba, 2022). The research shows that the statistical agency has been in the market for nearly 10 years. Nevertheless, in the surveyed population, as many as 200 entities have been in operation for less than 5 years. An interesting conclusion drawn from the project is that 7% of the agencies are affiliated with a domestic sector organization for PR firms (the Association of Public Relations Agencies and The Polish Public Relations Consultancies Association). In the surveyed group, 85% of all agencies have the number 70.21.Z listed within their Polish Classification of Activities (PKD) codes, meaning human relations (PR) and communications. However, 532 companies (57%) indicate them as the main ones. These results formed the basis not only for an extensive analysis of the sector, but also for identifying other distinguishing parameters (Polish Press Agency, 2022).

Thus, for the first time in the history of the Polish PR industry, we made an analysis to identify the key areas from the industry’s point of view, with a special focus on one sector, which is PR agencies. The sector has not been diagnosed before in such scope as was undertaken by the researchers who coauthored this article. This research has become the basis not only for drawing conclusions in the above area, but also for guiding further research that can be undertaken by scientific research teams.

The premise of the next stages of the ongoing research is to further analyse the collected data and use them, among other things, in the context of ways of communicating and perceiving the essence of PR in relation to the theory of the linguistic picture of the world (LPW1The term Linguistic Picture of the World (LPW) is understood here as a verbal interpretation of reality contained in language, which manifests itself in the form of a set of judgments about the world (Bartmiński, 2006).). Such formulated assumptions also became the main goal of the activities carried out in the creation of this article.

Methodology of the Study

In this study, the quantitative-corpus analysis methodology was used. The fundamental theoretical assumption behind both quantitative-corpus analysis and all discourse analysis (using both quantitative and qualitative methods) is the belief that a relatively uniform distinguishable image of a given social object/fact/phenomenon is deposited in the language used by representatives of a given social group (speakers of a given language, or, as in the research presented here, a narrower group, such as a professional group) (Berger & Luckmann, 2020) in the communication strategies, metaphors, and more broadly, the discursive strategies this group uses. In this case, the analysed group is PR professionals and, more specifically, pertaining to selected communication strategies implemented by them in the context of self-description2The category of self-description is taken from the field of social and communicative constructivism theory, which assumes that the basis of functioning of societies are constructions of reality that arise and persist in the course of communicative processes, that is, processes that are fundamentally symbolic (Wendland, 2011). of their professional activities.

Thus, the basis of the present research is the assumption that the language of a given social group (in this case, PR professionals) is a specific way of organizing social reality by the representatives of this group; it expresses a certain attitude to this reality, experience, a set of judgments and norms, and even a worldview (Mańczyk, 1982).

The basis of the methodology used here is, as mentioned, the methodological achievements of corpus linguistics and the lexicometric approach to language and discourse analysis (corpus-assisted discourse studies). The essence of this approach is the use of quantitative methods and computer tools (in this case, the Provalis software package) to reconstruct the linguistic worldview of the studied objects, the carriers and manifestations of which form a dedicated corpus of verbal expressions. Trying to explicitly define corpus linguistics is problematic; it basically deals with the principles and practice of using corpora in the study of language (Pawłowski, 2003; Stefanowitsch, 2020) with the tools of information technology (Sinclair, 1991). Corpus linguistics uses large collections of texts (corpora), which are selected according to established analytical principles and categories. Thus, actual language patterns are analysed. This approach draws on the apparatus of mathematical and statistical research, while the assignment of statistical analysis and the use of quantitative methods to study linguistic phenomena make it possible to isolate statistical groups in this matter for further analysis. According to Pawlowski (2001, 2003), the empirical and quantitative nature of the regularities under study implies the measurability and/or quantification of certain features of language.

The extracted corpora were subjected to quantitative-corpus analysis (Gries, 2014)3It is worth noting that the analyzed corpora are not large. This is a limitation that cannot be avoided, since the texts that are included in the corpora essentially exhaust the collection of such texts present in circulation (in terms of the state of the public relations market in Poland as of the date of the study). In this context, it should be emphasized that the analyzed corpora have a specialized character. It was also assumed that even those lexemes whose presence is limited (in terms of percentage representation values) can point to important phenomena in the context of the conclusions of the analysis (this applies, for example, to the lexeme ‘ethics’). It was also assumed that the ratio in terms of the frequency of lexemes within the analyzed corpus is essential., conducted with the use of the Provalis tool4Previously, this type of research in Poland was generally not conducted, with the exception of studies that were pilot in nature (Stasiuk-Krajewska, 2017).. In addition to the references to the LPW and the analysis of the frequency of lexemes, in the presentation of the methodological concept, it is worth noting the specificity of the agencies that were included in the two isolated text corpora (K1, name targeting the area of communication/PR and K2, no targeting in the name) (Stasiuk-Krajewska & Ulidis, 2018). For this purpose, statistical analysis was carried out in the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software based on cross-tabulations and the procedure for comparing averages. The results were tested for statistical significance (using nonparametric Mann–Whitney U tests for the two comparison groups and chi-square cross-tabulations). This provided a statistical picture of the research sample (Apanowicz, 2002) of 415 agencies, which were classified into the K1 and K2 corpora (a significant differentiating factor from the perspective of the entire article).

Profile of the Surveyed PR Agencies

The initial assumption of significant communication differences between K1 corpus agencies and K2 corpus agencies was confirmed by the data presented below. Agencies classified as K1 corpus are characterized by:

- a greater number of tabs on the website (the main menu is more fragmented, the internet user has more choices), as the average for K1 was 5.80 versus 5.40 in K2 (p = 0.049);

- a more detailed offer, as 82% of the websites include additional information beyond indicating just the name of the service/area of operation. In contrast, for K2, the above percentage was 73%, which suggests the generality of the offer (p = 0.040);

- a more PR–oriented self-description. The content on websites significantly more often includes terms indicating that the company sees itself through the prism of PR, for example, ‘we are a public relations agency’, ‘we have been operating in the PR services market since’. In the K1 corpus, 87% of such cases were observed, while in K2, the percentage for such positioning was twice as low (p < 0.001);

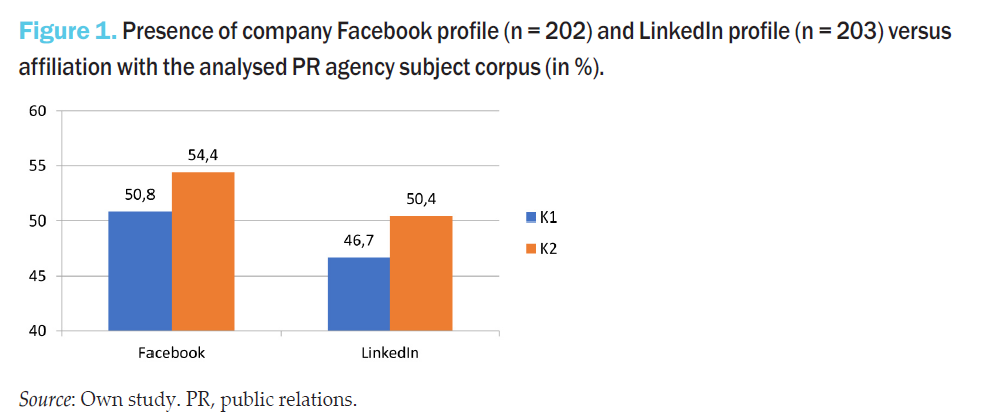

The activities in the possession of other communication tools (in addition to the website), through which the company can present content to the wider environment, are shown in Figure 1. In general, it can be seen that agencies from the K2 corpus are slightly more likely to have profiles on the analysed sites, although the results of statistical tests were not significant (p > 0.05).

In addition to the communication factors listed above, it is also worth noting the selected factors of a demographic-market nature. Agencies from the K1 corpus are almost twice as likely to operate as sole proprietorships. This legal form is found among 43% of agencies from K1 and 25% from K2 (p = 0.005). Also, agencies with lexemes related to communication and/or PR in their name are significantly more likely to have the PKD code 70.21.Z—meaning interpersonal relations (PR) and communication—86% versus 75% in K2, indicating logical consistency in the way the company is organized and named. There are also significant differences in accessibility to financial statements (which correlates with legal form), as it is easier to find this type of information for agencies in the K2 corpus (p < 0.001), for example, 52% of K2 companies have posted information for 2019, while in the K1 corpus, it was 38%. Meanwhile, the two compared corpora obtained similar statistics when it came to duration of operation in the market, frequency of membership in a sector organization, and location of the company’s headquarters in a given province (the lack of significant differences is evidenced by p > 0.05).

The above data indicate that companies in the K1 corpus, therefore, those that refer in their name to communications/PR conduct more elaborate and detailed communications as well as consistently and unambiguously locate their self-description in the area of PR—not only in the name, but also in the more elaborate self-presentation texts on websites and even in the PKD codes.

Analysis of Text Corpora

We analysed text corpora, created from textual materials taken from the websites of PR agencies. These were texts posted in the ‘About Us’ tab or in tabs with similar specificity and communication function, where PR companies put information about their business profile and what they consider to be their strengths, specificity, and differentiator in the market. The similar function of the texts determines the similarities in the way communication is carried out on the agency–environment line and methodologically legitimizes the comparison of these texts. For the purposes of the study, we used the database of the Exacto agency, which owns a systematically updated database of PR companies and conducts periodic research projects on the environment of PR professionals in Poland (Polish Press Agency, 2022).

The motivation for such constructed corpora (based on tabs containing references to the identity, mission, vision, or profile of the companies) was the assumption that such texts most fully represent the self-construction (self-description) of the agency in the context of offering PR services (Stasiuk-Krajewska, 2012). As mentioned, these are texts that present both the agency’s offerings (thus indicating the defining framework, scope of categories, and PR competencies) and also name what distinguishes the agency, by its own declaration, in the market. It is also important to indicate why its offerings are attractive and/or of high quality (thus, agencies point to the qualities constructed as desirable characteristics of professional PR).

The analysis included two text corpora of these agencies that met the input criteria. First, at the time of the study, they had a functioning company website, and second, the site had an ‘about us’ or functionally related tab. Agencies that only have a social media profile were not included, as it was considered that the medium of communication (in this case, Facebook) models the content posted there in a specific way, so texts from there cannot be considered equivalent to those from websites. The final unit of analysis was 415 companies—or 44% of the total PR agency database in Poland. The stated assumptions imply the need to infer only within agencies with higher information potential. This is an important observation, which also points to the underdeveloped communications background of a significant number of Polish PR firms, since as many as 56% of such entities do not meet the two above-mentioned input criteria—that is, they do not have the final basic tool for acquiring potential clients online5The fact that the presence of a company website and its proper/correct functioning is a matter of interest to Internet users is indicated, among others by (Umpirowicz, 2001; Zborowski, 2013)..

Following this, the corpus was divided into two distinct segments (Table 1). The first was created based on texts that come from the websites of agencies that have the word communication or PR in their names (K1). The other—on the basis of texts from the websites of agencies that do not have the above-mentioned words in their names (K2). Since the study focused on communicative reality (the construction of social reality or the LPW), it was assumed that the communicative factor of the agency’s name was also worth considering as a differentiating criterion. It was assumed that the decision to include the terms communication or public relations in the name could correlate with the different self-description and linguistic construction of PR, as well as condition differences in the way the agency was organized. These assumptions have been partially confirmed.

The K1 corpus was based on texts from 167 functioning websites. The K2 corpus, on the other hand, was based on texts present on 248 eligible websites. Among the texts that made it into the corpus6It is worth noting that we considered the title to be the text that appears when you enter the site and expand the top menu. There were situations in which the texts had different titles on the menu and after entering the tab., those appearing in the tab under the name ‘About Us’ dominated, although such a tab name was more often present in the K1 corpus (as much as 24% points of difference). As can be clearly seen, PR agencies that directly include the lexeme communication/PR in their name are more likely to pay attention to self-construction in the context of offering PR services, and thus provide a greater volume of knowledge through the company’s website to the environment. This conclusion supports earlier statements about greater communication commitment and greater awareness of the importance of rich and relevant communication among agencies in the K1 corpus.

In addition, K2 proved to be a less informative corpus, as evidenced by a lower average of words (six fewer words) and characters (25 fewer on average). On the other hand, the more common corpus was by far K2 (60%), meaning that fewer specialized lexemes appeared in this corpus, or those explicitly targeting the agency’s communications and PR area, although it would seem that such an arrangement could be an element of competitive advantage and a nod to the classical approach to PR. Meanwhile, research has confirmed that emphasizing, using linguistic means, a particular specialization is not a dominant phenomenon. Presumably, it will increasingly disappear over time, bearing in mind, for example, the tendency of PR companies to build the image of a full-service agency. Following this, the corpus was divided into two distinct segments (Table 1).

No title7This category included texts that appeared immediately upon entering the Web site, without expanding the menu. – from table 1

function8For K1: ‘operating philosophy’, ‘why us’, ’resume’, ‘us’, ‘get to know us’, ‘our strengths’, ‘our mission’, ‘what makes us different’, ‘mission and history’, ‘two words about us’; for K2: ‘what’s important’, ‘us’, ‘our story’, ‘welcome’, ‘this is us’, ‘our team’, ‘Hi!’, ‘from us’, ‘ideas’, ‘get to know us’, ‘why us’, ‘benefits of cooperation’. – from table 1

The data already presented above show significant differences in the linguistic construction of PR in the two groups of agencies. As it seems, K2 included texts that can be considered a bit more diverse, individualized, and ‘creative’. Despite the fact that the percentage of texts with titles classified in the ‘other’ category (the last row of the table) is comparable for both corpora, the very collection that these texts form is more homogeneous in the case of K1. In addition, the K1 corpus is characterized by the occurrence of more standard titles like ‘About Us’, as well as duplication of the company’s own name. In the case of K2, on average one in five texts did not have a title, although this group of companies compensates for this lack most often with visual communication (photos, graphics, or videos). It is also worth noting that in this corpus (K2), as soon as the user enters the site, short texts appear to attract the attention of the internet user, often correlated with the image. This type of feature should also be considered as a manifestation of the desire for a certain unconventionality in communication, and therefore, a kind of ambiguity in terms of self-description, avoiding placement within a particular professional field, in this case, the field of PR.

The lexical structure of the K1 corpus—which included texts from the websites of agencies that use the term public relations, PR, or communications in their names—made it possible to observe a more strongly developed pro-client approach. It is also visible in the K2 body, but occurs at a lower intensity (Figure 2).

Lexical structure of K1 and K2 – most frequent lexemes (in %)9At this point, it is essential to emphasize that the term “lexeme” is not used here precisely. In most cases, a lexeme is a unit formed by lemmatization (that is, a certain abstract linguistic unit that includes the lexical meaning and all the forms a word can take). However, in some cases, several lexemes were considered to refer to a relatively coherent semantic field that is functional as part of the linguistic construction of social reality. For example: the category of naj- includes adjectives in the highest grade. Since all such forms have a positive meaning in the analyzed corpus, they were included in a common category, assuming that, treated in this way, they constitute a certain coherent unit in the context of the linguistic construction of reality. In addition, lexemes without semantic function (conjunctions, prepositions, or the reflexive pronoun itself) were not included in the chart.

As can be seen, the lexeme with the highest frequency in K1 is the lexeme client (1.39%). This clearly indicates communication in relation to the needs of the recipient, to the client, and the client’s expectations of the agency. Therefore, this is communication based on relationship building, which is further reinforced by the high frequency of the lexeme our (our company, our agency, our services, our offer)—communication of the offer is therefore based on building a relationship between ‘us’ (the agency) and ‘you’ (clients)—0.95%. In addition, PR is seen here as a team activity, with the agencies signalling at the same time a high level of involvement in the activities carried out, identifying with them (this is also the function of the pronoun our). PR is therefore defined by a kind of activism (action and involvement), rather than, for example, analysis or research (high frequency of the lexemes action—1.01% and work—0.83%).

The lexeme company (0.96%) also ranks high in the K1 corpus. Combined with the position of the lexeme client, this indicates that PR activities are rather located in the arena of narrowly defined market activities. To put it another way—it refers to PR as an activity aimed primarily at commercial clients—lexemes that could indicate a different approach, such as organization (0.49%), group (0.18%) or institution (0.13%), are placed low. PR agencies are companies that work for other companies constructed in the market paradigm as clients. All this is clearly located in the field of business (a lexeme, by the way, also with a relatively high frequency—0.51%).

The data presented above also clearly indicate that PR is understood essentially as communication, which is strategic in nature and implemented in a project model. This communication should be effective, while the most significant competitive advantage in the self-description of agencies from the K1 corpus is, as most often emphasized, experience—0.68% (note that this is not, for example, innovation, which, after all, one could easily imagine). This makes the PR industry appear rather reserved, not to say conservative. On the other hand, it is not surprising that experience is an important value for professionals working, generally speaking, on credibility and trust.

It is worth noting the high frequency of the set of adjectives in the highest grade (most—0.82%); agencies like to brag directly, incorporating the language of (self) promotion and direct persuasion into their self-descriptions. In the context of the expected competencies of PR industry professionals, this conclusion may be somewhat disturbing. Categories such as media (0.75%) and marketing (0.51%) also ranked high. Overall, the 20 most frequent lexemes account for 15.21% of the total K1 corpus, while for K2, the rate was slightly lower—13.35%. In addition, in both corpora, the most frequently occurring lexemes were comparable, for example, places 1–4 were distributed in the same way.

In the case of the K2 corpus (generated from texts posted on the websites of agencies that do not have the terms PR, PR, or communication in their names), some of the observations that were made about the K1 corpus remain valid. An essential part of the linguistic worldview is the construction of the relationship between the agency and the client, it is still important to act and work for clients. Looking for common denominators, it can be seen that agencies continue to communicate themselves as teams that identify strongly with what they do (here, additionally, there is a high frequency of the form we are—0.51%10This form was not lemmatized precisely because of its significant frequency in the analyzed corpus.), aiming to establish a close relationship with the client. We still find a lot of direct self-presentation and a lot of declarativeness in the texts. PR activities also at K2 are clearly located in the market sector, defined as a project and strategic activity, the quality of which is guaranteed by the experience of those who carry them out (in this case, the agency and/or its employees).

Besides the many similarities between the K1 and K2, there are also noteworthy differences. The table 2 shows a comparison of the results of the analysis of the two corpora. It includes a summary of only those lexemes for which the frequency clearly—by the terms of the presented study—differs by at least ± 0.15% points in the intergroup cross-section. The gradation used (in order from the largest to the smallest difference) allowed us to observe more than a dozen interesting cases (Table 2).

First of all, it is worth noting that the data presented confirm the assumption made as the basis for separating the corpora according to the criteria of presence (K1) or absence (K2) of the public relations/PR and/or communication categories in the name. It is clear that agencies from the K1 corpus consistently, in their self-description, refer to the above-mentioned categories. In particular, the frequency of the terms public relations and PR is significantly higher here (both if we treat them as separate categories and when we decide to add up their frequency value). In the latter aspect, the results are 1.60% for K1 versus 0.95% in K2. In addition, with regard to the K1 corpus, a link to media relations—still a key sphere of PR agency activity (Tworzydło et al., 2020)—is more strongly outlined. This is confirmed by frequency differences occurring with the lexeme effect (in the context of measuring PR effectiveness), journalism (in the context of a professional group and the role of the media in the work of PR professionals), effective (in the context of communication activities carried out or crisis management), or communication (in the context of the exchange and flow of information on the agency–media line). It is also necessary to emphasize the high frequency of lexemes media (analogy: with the media, in the media, media relations, etc.) in the K1 corpus. It is evident that defining PR by building and maintaining relationships with the media (journalists) and carrying out activities of a journalistic nature are still a very strong trend in the industry. Similarly, the presence of the lexeme event should be interpreted as indicating an important area of PR activity/competence.

At the same time, the frequency of the lexemes marketing and advertising is noticeably lower for agencies in the first corpus, which may indicate a higher degree of specialization in the field of PR and a higher awareness regarding the differences between PR and marketing or advertising (or, more precisely, the lack of validity of equating these concepts). The category of image, traditionally used in defining or specifying (including colloquially) the concept of PR, also appears somewhat more frequently in K1. As it seems, the higher presence in this corpus of the lexeme relations (deviation 0.12) should be similarly interpreted. Also absent from the K1 corpus (among the first 20 ‘frequency leaders’) is the lexeme brand, which already appears in the 12th place in the K2 corpus.

Interestingly, agencies from the K1 corpus—that is, let us recall, those more clearly located in the PR field—communicate themselves in a more ‘marketing’ way, so to speak: persuasively, through far-reaching promises, while being less specific. Here we can clearly see a higher frequency of lexemes from the most- group (0.32% points higher value), but also other lexemes such as all (0.11), wide (0.12), or possible (0.22) on the one hand; good (0.14) or excellent (0.10) on the other11So the higher frequency of the lexeme our may be relevant here. This is because it is a possessive pronoun often used in marketing and advertising communications (‘our company,’ ‘our offer,’ ‘our product,’ etc.).. What emerges from this type of communication is, first, the construction of PR as a field that is very broad and imprecisely defined, and second, PR agencies and professionals as such, who tend to raise great expectations among their clients by making many ambitious but unspecific promises. Needless to say, such a linguistic construction is not beneficial to the field of PR12One of the elements that make up the index of the condition of the PR industry in Poland is an evaluation of the aspect related to whether the expression ‘public relations’ evokes commonly negative or positive associations. The index is calculated systematically every two years, with the first edition taking place in 2017. The study involves PR specialists from all over Poland (Tworzydło et al., 2017)..

Agencies more strongly attributed to the field of PR (K1 corpus) also communicate more clearly through the promise of the effectiveness of their actions (lexemes effect, effective, and success). It is worth noting that this very effectiveness (for the three aforementioned lexemes, there is a difference of 0.5% points of advantage in favour of K1), as opposed, for example, to creativity or creation/creator (present, after all, in the K2 corpus), also says a lot about how ‘good’ PR is perceived. In the K1 corpus, the tendency to refer to commitment (the lexeme work) is also slightly stronger. You can also see a shift away from the (still obviously very important) customer category towards the organization category13However, it should be emphasized here that the lexeme ‘organization’ also refers to the phrase ‘organizing something,’ so its relatively high frequency can be misleading. This issue would require additional investigation, but the limited volume of the corpus makes such an analysis (taking into account the dominant phrases in which the lexeme occurs) impossible..

The comparative analysis presented above also indicates that the narratives from the K1 corpus make more reference to authority and professional knowledge (obviously the lexemes knowledge/we know, but also the aforementioned specialist). It is also worth noting the slightly higher frequency of the lexeme ethics (0.09 points), which is practically absent in K2 (0.01%).

Summary

Separating the two text corpora according to the criterion of naming PR agencies, followed by a quantitative-corpus analysis, allowed us to observe differences in the communication self-description of PR agencies in Poland. Differences were also revealed in the website communication techniques used by agencies whose names belong to separate corpus (such as the number of tabs on the website or the detailing of the offer). The lexical analysis of the corpora also made it possible to identify those elements that—in the eyes of market practitioners—are considered important for professional PR.

Corpus one is formed by agency names that contain the word communication and/or public relations/PR. Agencies whose names have entered this corpus are characterized by a greater number of tabs on their websites and more detailed communication of their offerings. However, from the point of view of self-description, it seems more significant that these agencies, in line with the assumption of locating themselves more clearly and unambiguously in the professional PR field, communicate in a more standardized and at the same time elaborate way—they use more words for less images. Their communication more often refers directly to the category of PR and to those areas traditionally considered constitutive for PR (media relations or event organization). It is therefore, so to speak, a more conservative communication, referring to the traditionally indicated techniques and areas of PR.

Agencies that do not have communication and/or public relations/PR elements in their name create their self-description as more diverse and creative, less textual, and more visual. Much more often, they refer to the categories of marketing and advertising or brand. In this corpus, there is a slightly greater tendency to ‘experiment’ in terms of titles, as indicated by the presence of the ‘other’ category with completely nonstandard ideas for titles of the texts of the type analysed. The above conclusion is also confirmed by some difference in the length of the texts depending on the corpus—in K2, the texts are slightly shorter. In addition, the K2 corpus more strongly aggregates solutions from scopes traditionally not included in PR, such as marketing and branding.

The lexical analysis of the two corpora also indicated some similarities between them, which can be considered relevant to the self-description of the PR industry in Poland. The self-description constructs the company mainly in relation to the customer and considers efficiency and strategic thinking as the essential qualities of good PR and experience and teamwork as competitive advantages in the industry.

The quantitative-corpus analysis thus identified two, significantly different, self-constructions of PR companies operating on the Polish market.

Given the number of websites (and therefore market entities) whose content constituted both corpora (167 for K1 and 248 for K2), there is a reasonable assumption that, over time, PR agencies will increasingly move away from the use of the lexemes communication and public relations in their name, as such a tendency definitely dominates the analysed material. This is related to the challenges currently being faced by the entire PR industry in Poland. The key is the competition from other disciplines/areas, such as the aforementioned marketing, advertising, or branding, as well as the increasing tendency to carry out PR activities with a company’s own resources rather than by external specialized agencies or, finally, the growing importance of new communication technologies (Tworzydło et al., 2022). In addition, the agency market is changing rapidly, resulting, among other things, in the desire to be a full-service agency, or at least to present its activities in this way (on a self-declaration basis), and regardless of its competence, human resources, as well as the proportion in the implementation of projects with its own resources and those where it becomes necessary to rely on outsourcing (Szuba, 2022). Therefore, the authors speculate that the K1 corpus will fade in the agency sector structure, mainly by the fact that new companies will not want to position themselves exclusively as agencies strictly dedicated to the PR field, and will be more interested in building a 360 agency image. Therefore, it is necessary to repeat the study and see what the structural arrangement of the corpora will be, such as at the end of the second decade of the 21st century. It is also worth considering how this change translates into the colloquial understanding and scientific definition of PR as a professional community14On the category of professional community cf. (Stasiuk-Krajewska, 2018)., and consequently, what will be the key competencies of the PR professional of the future.

References

1. Apanowicz, J. (2002). Metodologia ogólna. Wydawnictwo Bernardinum.

2. Bartmiński, J. (2006). Językowe podstawy obrazu świata. Wydawnictwo UMCS.

3. Berger, P., & Luckmann, T. (2020). Społeczne tworzenie rzeczywistości. PWN.

4. Gries, S. (2014). Quantitative corpus approaches to linguistic analysis: seven or eight levels of resolution and the lessons they teach us. In Irma Taavitsainen, Merja Kytö, Claudia Claridge, & Jeremy Smith (eds.), Developments in English: expanding electronic evidence, 29-47. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

5. Mańczyk, A. (1982). Wspólnota językowa i jej obraz świata. Krytyczne uwagi do teorii językowej Leo Weisgerbera. Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Pedagogicznej.

6. PAP. (2022). Rynek agencji public relations w Polsce to 934 podmioty. dostęp May 19, 2022, from https://www.pap.pl/mediaroom/915534%2Crynek-agencji-public-relations-w-polsce-934-podmioty-szacowany-przychod-ze

7. Pawłowski, A. (2001). Metody kwantytatywne w sekwencyjnej analizie tekstu. Wyd. Uniwersytetów Warszawskiego i Wrocławskiego.

8. Pawłowski, A. (2003). Lingwistyka korpusowa—perspektywy i zagrożenia. Polonica, 22/23, pp.19‒31.

9. Sinclair, J. (1991). Corpus, concordance, collocation. Oxford University Press.

10. Stasiuk-Krajewska, K. (2012). Public Relations jako system ekspercki późnej nowoczesności – tożsamość i samorefleksja. [w] M. Graszewicza (pod red), Teorie komunikacji i mediów 5. Oficyna Wydawnicza ATUT, pp. 174‒184.

11. Stasiuk-Krajewska, K. (2017). Public Relations – między samoopisem a autoprezentacją. Badania własne. Studia Ekonomiczne. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Katowicach, 313, pp. 173‒186.

12. Stasiuk-Krajewska, K. (2018). Media i dziennikarstwo. Struktury dyskursu i hegemonia. Dom Wydawniczy Elipsa.

13. Stasiuk-Krajewska, K., & Ulidis, M. (2018). Language, identity and discourse – between theory and methodology. The idea of empirical research. Dziennikarstwo i Media. Metodologie i praktyki, 9, pp. 139‒156.

14. Stefanowitsch, A. (2020). Corpus linguistics: A guide to the methodology. Language Science Press.

15. Szuba, P. (2022). Komunikacja kryzysowa. Analiza sektora agencji public relations. Wydawnictwo Newsline.

16. Tworzydło, D., Gawroński, S., & Szuba, P. (2020). Importance and role of CSR and stakeholder engagement strategy in polish companies in the context of activities of experts handling public relations. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management, 28(1), 64–70.

17. Tworzydło, D., Gawroński, S., Szuba, P., & Kuca, P. (2022). Satisfaction level of public relations practitioners with their profession in the context of the challenges of the PR industry in Poland. International Journal of Work Organisation and Emotion, 13(1), pp. 37–56.

18. Tworzydło, D., & Szuba, P. (2022). Rynek agencji public relations w Polsce. Stan i perspektywy po pandemii COVID-19. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 44(2), pp. 71‒82.

19. Tworzydło, D., Szuba, P., & Zajic, M. (2017). Analiza kondycji branży public relations. Newsline.

20.Umpirowicz, S. (2001). Internetowe narzędzia public relations. In S. Ślusarczyk, J. Świda, & D. Tworzydło (Eds.), Public relations w kształtowaniu pozycji konkurencyjnej organizacji (t. 2). Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Informatyki i Zarządzania.

21.Wendland, M. (2011). Konstruktywizm komunikacyjny. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Instytutu Filozofii Uniwersytetu im. Adama Mickiewicza.

22.Zborowski, M. (2013). Modelowanie witryn internetowych uczelni wyższych o profilu ekonomicznym [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. Uniwersytet Warszawski.

Dariusz Tworzydło, PhD — Professor at University of Warsaw. Is an expert in economics, social research, and public relations. An academic at the University of Warsaw, Faculty of Journalism, Information and Book Studies. President of the Management Board of Exacto sp. z o.o. and Newsline sp. z o.o. Author of over 280 scientific and journalistic articles, scripts, research papers, and books. Member of the Polish Public Relations Association.

Karina Stasiuk-Krajewska — PhD in social communication sciences and media, Professor at SWPS University. Author of approximately one hundred scientific publications. Her research interests include counteracting disinformation, professional ethics and axiology of communication, and discourse analysis and theory. She directs the work of the Central European Digitla Media Observatory in Poland (CEDMO). Expert of the International Fact-Checking Network and EDMO’s Group of Experts on Structural Indicators for the Code of Practice on Disinformation. Coordinator of the PR for Science – Science for PR club in the Polish Public Relations Association.

Przemysław Szuba, PhD — Graduate of the Catholic University of Lublin, majoring in Sociology and Journalism and Social Communication. A specialist in quantitative and qualitative research. He is a data analyst. Co-author of several hundred research projects and scientific articles. Author of the book „Crisis Communication: Analysis of the Public Relations Agency Sector.” Lecturer at WSEI University and WSB Merito University in Wroclaw.