- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Selected Aspects of Collaboration Among Polish Enterprises in Terms of Innovation Activity

Jerzy Baruk

Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, Faculty of Economics, Institute of Management, Poland — a retired researcher and teaching faculty member at the Institute of Management, Faculty of Economics, Maria Curie-Skłodowska University in Lublin, 5 M. Curie-Skłodowskiej Sq., 20-031 Lublin, Poland

E-mail: jerzy.baruk@poczta.onet.pl

ORCID: 0000-0002-7515-0535

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2025-0002

Abstrakt:

This study examines the prevalence and dynamics of innovation-related collaboration among Polish industrial and service enterprises. Despite the well-documented benefits of collaboration in fostering innovation, empirical data indicate that such collaboration remains relatively uncommon and inconsistent across different Polish business sectors. Using a combination of critical literature analysis, statistical evaluation, and comparative methods, this study identifies key trends in enterprise innovation activity and assesses the role of managerial decision-making in shaping cooperative initiatives. The findings suggest that innovation-related collaboration is often incidental rather than strategically managed, with a significant gap between theoretical models of innovation management and their practical implementation. Large enterprises are more likely to engage in cooperative innovation, whereas small and medium-sized enterprises demonstrate lower participation rates. Furthermore, collaboration primarily occurs with domestic partners, with limited engagement in international networks. The study underscores the need for a more structured approach to innovation management, including enhanced knowledge integration, increased managerial awareness of cooperation benefits, and the development of policies that incentivize strategic partnerships. Addressing these challenges could improve Poland’s innovation ecosystem, aligning it more closely with international best practices.

MINIB, 2025, Vol. 55, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2025-0002

P. 17-38

Published March 19, 2025

Selected Aspects of Collaboration Among Polish Enterprises in Terms of Innovation Activity

1. Introduction

Every organization – be it industrial or service-oriented – that seeks to develop, to compete effectively, and to create value needs to systemically generate and implement innovations across all its areas of operation. In economically developed countries, innovation is treated as a driving force (Hilmersson & Hilmersson, 2021, pp. 43‒49; Latif, 2024) that enables:

1) improved organizational economics,

2) opening up of new markets,

3) enriched knowledge resources and their creative application,

4) renewed industrial structures,

5) effective achievement of developmental goals,

6) expansion and diversification of products, services, and related markets,

7) implementation of new production, supply, and distribution methods,

8) the introduction of new methods of management and work organization, as well as changes in working conditions and staff qualifications,

9) staff integration and stronger relationships with customers,

10) improved quality of work, production standards, workplace health and safety, and environmental protection,

11) enhanced teamwork and collaboration with customers,

12) value creation,

13) increased living standards of societies, etc.

Therefore, it should be a guiding principle of management to systematically enhance the innovativeness of the organizations managed, continually striving to transform them into truly innovative enterprises. However, these issues are often marginalized in business operations. One hallmark of innovative organizations is the active involvement of managers and employees in fostering innovative activity, while remaining guided by shared values (Peters & Waterman, 2000, p. 47). This is supported by the strong correlation that has been found between the introduction of new products and the success of organizations (Tidd & Bessant, 2013, p. 26). Moreover, every manager needs to remember that any market advantage attained through innovation will inevitably diminish over time, due to innovative efforts on the part of other organizations. Therefore, successful organizations have to establish systematic, methodical, and organized processes to ensure the continued creation and practical implementation of innovations.

Innovation is of great economic and social importance, for organizations and societies alike. However, the various processes involved in creating, implementing, and managing innovations often encounter significant challenges. Numerous technical, technological, legal, economic, social and organizational barriers can hinder operational and development activities. These barriers, as highlighted in the literature, can be categorized into three groups (Ordoñez-Gutiérrez et al., 2023, pp. 1–22): 1) cost-related barriers (involving insufficient internal or external financial resources), 2) knowledge-related barriers (a lack of employment opportunities for employees with appropriate qualifications, limited knowledge of market rules, inadequate information about the company’s innovation needs), and 3) market knowledge related barriers (an inability to introduce innovations to the market effectively, making it impossible to recover the costs of their development).

Other scholars have proposed other classifications. Indrawati et al. (2020, p. 555) identified the following barriers: 1) those related to the financing of innovation in enterprises (high costs of innovation, difficulties in obtaining credit from financial institutions, high interest rates), 2) barriers related to government support (minimum financial assistance from the government, a lack of training from the government in the field of innovation, non-targeted government aid for innovative equipment), 3) those related to business partners (no suppliers as business partners, no marketing agencies as business partners), 4) those related to the quality of human resources (difficulties in recruiting high-quality employees, a lack of employee competence, resistance of employees to innovative changes, relatively high resistance of business owners to innovative changes, a lack of knowledge of business owners about innovation), 5) economic conditions (difficulty in obtaining innovative equipment, unstable economy, low purchasing power). Das et al. (2018, p. 99), in turn, have classified barriers into 1) internal (organizational strategy, organizational architecture, leadership, organizational culture, R&D organization, motivational incentives, negative attitude, inadequate innovative competences, unfavorable organizational structure); and 2) external (market dynamics, competitor behavior, market and technological turbulence, customer resistance, ecosystem dynamics, underdeveloped information network).

Recognizing such barriers can support rational decision-making and enhance innovation processes. One way to reduce the negative effects of these barriers to innovative activity is to engage in organized and rationally-managed collaboration among enterprises in the field of creating and implementing innovations.

The research problem addressed herein can be framed as follows: To what extent is collaboration in innovative activity prevalent among Polish enterprises? How dynamic is this collaboration, and is it an element of rational management? To address these questions, this study examines: 1) the proportion of innovative enterprises among the total number of companies, 2) the percentage of innovatively active enterprises, 3) the percentage of enterprises engaging in innovation-related collaboration, 4) the structure of collaborative partners, 5) the percentage of enterprises collaborating within cluster initiatives.

Via these issues, this study explores the role of managerial involvement in overcoming innovation barriers. By addressing these challenges, organizations can improve innovation management, enhancing competitiveness, value creation, knowledge expansion, and market growth.

A key assumption underlying this study is that the relatively low percentage of innovatively active organizations in Poland that decide to collaborate in the field of innovative activity is a consequence of a certain gap between theoretical advancements in innovative management and the willingness of managers to adopt and implement these concepts in practice.

Therefore, the objective of this publication is to assess the prevalence and dynamics of collaboration in innovation among Polish industrial and service enterprises and to demonstrate that such cooperation is not yet a common component of managerial decision-making. This state of affairs stands in contrast to the model solutions presented in the literature.

The article is structured into an introduction, followed by a critical literature review, research methodology, presentation of research findings and their analysis; and summary of the findings as well as suggestions for further research.

2. Literature review

Due to its high importance for the development of organizations, regions and entire economies – as well as in value creation – innovation has been extensively explored in the research literature, from a variety of technical, economic, management, organizational, sociological and psychological perspectives (Brzeziński, 2001; Sosnowska et al. 2000; Świtalski, 2005; Janasz & Kozioł-Nadolna, 2011; Zangara & Filice, 2024, pp. 360–383; Ullah et al., 2024, pp. 1967–1985). Authors have focused their attention on explaining the essence of innovation, classifying innovations, identifying innovation’s role in the development of organizations, increasing their competitiveness, improving management efficiency, improving management and the qualifications of employees, creating innovations as a team and organizing the national innovation system, etc. (Baruk, 2009, pp. 93–103; Świadek, 2021; Kozioł-Nadolna, 2022). Note that despite the extent of this literature, no uniform, universally applicable definition of innovation has yet been developed. The vagueness and diversity of definitions presented in the literature makes it difficult to understand the essence of innovation and hinders communication between theoreticians and practitioners, contributing to interpretative confusion (Baruk, 2022, pp. 10–23; Baregheh et al., 2009, p. 1334).

Since innovation activity faces various types of external and internal obstacles, some authors have attempted to identify such obstacles and their impact on the universality of creating and implementing innovations, as well as on the effectiveness of innovative activity. As noted above, three groups of barriers to innovative activity are most often indicated (Das et al., 2018, p. 99; Carvache-Franco et al., 2022, p. 1–17; Martínez-Azúa & Sama-Berrocal, 2022, p. 1–25): (a) cost and financial barriers, (b) knowledge barriers, (c) market barriers. Social barriers are also significant – managerial resistance, especially among middle management, and lack of employee engagement (Alshwayat et al., 2023, pp. 159–170).

Given the negative impact of these barriers on the efficiency of innovative activities, it is crucial to seek ways to eliminate or at least mitigate them. One such strategy widely discussed in the literature involves fostering collaboration with other business entities / research centers. Well-organized cooperation of this sort has been shown to have numerous advantages (Hardwick et al., 2013, pp. 4–21): reduced risk of failure, lower costs of innovation activities, improved effectiveness, rational use of knowledge possessed by cooperating organizations, expanding and enriching this knowledge, and shortened innovation development cycles, etc.

In general, cooperation in innovation can adopt four broad forms: distant, translated, definite and developed (Lind et al. 2013, pp. 70–91; Wong et al., 2018, pp. 316–332; Yunus, 2018, pp. 350–370). Collaboration is recognized as one of the four key elements of innovation – alongside ideas, implementation and value creation (Cowan et al., 2009; Watkins, 2024).

Since innovation relies on knowledge, numerous authors have explored the relationship between knowledge creation, innovation, and knowledge management (Baruk, 2023, pp. 43–55; Nonaka & Takeuchi, 2000; Kowalczyk & Nogalski, 2007; Baruk, 2009; Baruk, 2018, pp. 83–110; Baruk, 2011, pp.113–127). The function linking knowledge creation to innovation is undoubtedly the efficient management of knowledge and innovation within a single system. However, how to best achieve such a systemic approach remains an open problem challenge in the literature. Theoretical and empirical research on knowledge and innovation management continues to offer valuable insights, especially for leaders managing modern enterprises (Baruk, 2021, pp. 14–21; Baruk, 2022, pp. 10–23; Tidd & Bessant, 2013; Baruk, 2015, pp. 121–145).

5. Research methodology

This study is based on empirical research conducted by Poland’s Central Statistical Office (GUS) on the innovative activity of enterprises in Poland in 2014–2022. These surveys covered all industrial and service enterprises with 10 or more employees and were conducted as part of the international research program Community Innovation Survey (CIS), using the standardized PNT–02 questionnaire. The results of these studies were presented in the publications GUS (2017, 2019, 2020, 2023).

Numerical data taken from these publications enabled a detailed interpretation of the studied phenomenon in terms of its universality and dynamics. Additionally, they also allowed for the verification of the following detailed research questions:

1) Was innovation-related collaboration an element of rational decision-making processes in Polish industrial and service organizations?

2) How prevalent was collaboration in innovative activities?

3) What were the dynamics of such cooperation?

4) Who were the collaborating partners?

5) Was a cluster participation a significant form of cooperation?

The following research methods were employed in this study: 1) critical and cognitive analysis of selected literature on the subject, 2) descriptive and comparative methods, 3) statistical analysis, 4) the projective method. These methods facilitated the interpretation of key concepts, an overview of the current knowledge base, barriers accompanying innovative activity, as well as the universality and dynamics of the use of cooperation in Polish industrial and service organizations. Additionally, the projective method was used to outline potential strategies for improving the management of collaborative innovative activities.

Research results and discussion

1) The level of innovation at Polish enterprises and its dynamics in 2016–2022

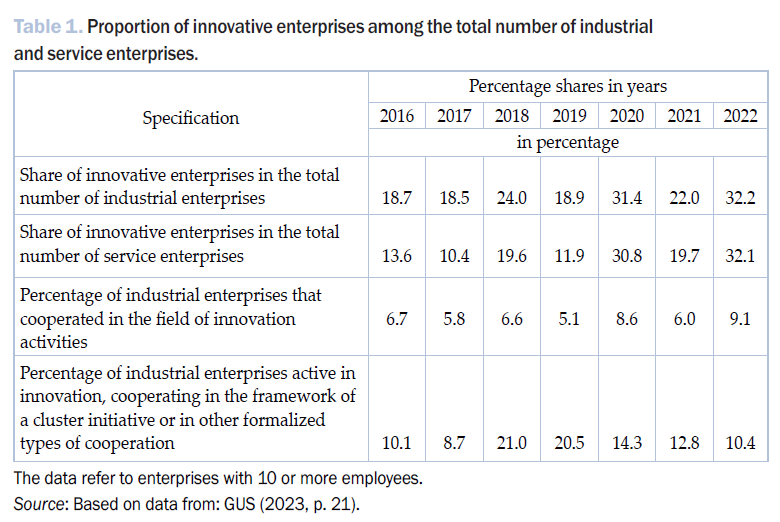

The level of innovation can be assessed using various indicators, one of which is the proportion of innovative enterprises among the total number of business entities. As Table 1 shows, in 2016–2022, the share of innovative industrial enterprises in the total number of Polish enterprises in this sector was at an average level of 23.7%. This measure notably fluctuated over subsequent years, reaching its highest value in 2022 – over 32%. Compared to 2016, this represents an increase of 13.5 percentage point.

A key finding is the low percentage of industrial enterprises engaging in innovation cooperation, which remained below 10% throughout the study period (peaking at 9.1% in 2022). Additionally, industrial enterprises that were active in innovation undertook cooperation within the framework of cluster initiatives, with a participation rate of 14%. The highest values were observed in 2018 (21%) and 2019 (20.5%).

In the service sector, the average proportion of innovative enterprises was 19.7% – 4 percentage points less than for the industrial sector. Throughout the analyzed period, the percentage of innovative enterprises in services was consistently lower than in industry, with the largest gap coming in 2017, at 8.1 percentage points.

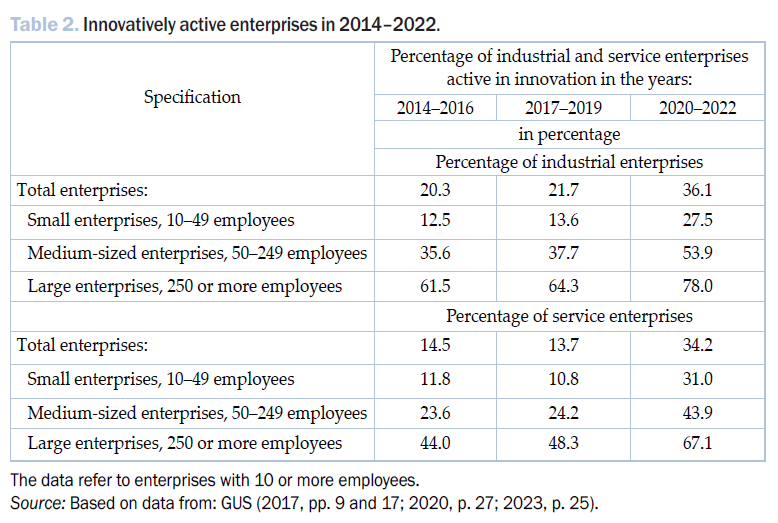

Engagement in collaborative innovation is typically influenced by the overall level of innovative activity within business entities. As shown in Table 2, the average percentage of innovatively active enterprises was 26% in the industrial sector and 20.8% in the services sector. A positive trend was the growing percentage of innovatively active entities in both sectors and within individual categories of enterprises. However, a decline was observed in the services sector in 2017–2019, where the share of innovatively active enterprises decreased by 0.8 percentage points compared to the previous period. A similar trend occurred among small enterprises, where in the corresponding period the proportion of innovatively active companies decreased by 1 percentage points.

A key characteristic of innovative activity is its correlation with enterprise size, measured by the number of employees. As shown in Table 2, the prevalence of innovatively active companies increases with enterprise size in both the industrial and service sectors. The lowest percentage of innovatively active firms was recorded among small enterprises, while the highest was observed among large enterprises. Notably, on average, in the European Union (2018–2020), 52.7% of enterprises engaged in innovative activities, whereas in Poland, the figure was only 34.9%, reflecting a 17.8 percentage point (p.p.) gap (EUROSTAT).

2) Prevalence of innovation-related collaboration among innovatively active enterprises

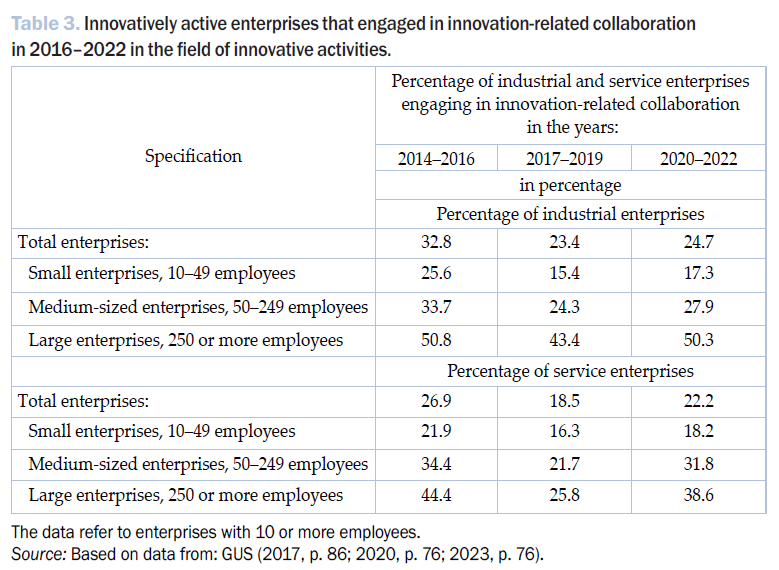

One of the key questions for this study is: What percentage of innovatively active enterprises engage in innovation-related cooperation? As Table 3 shows, in 2014–2016, almost one-third of innovatively active enterprises engaged in cooperation. However, this percentage declined by 9.4 p.p. in 2017–2019 and further by 8.1 p.p. in 2020–2022. Small enterprises were the least likely to cooperate, with only one in four firms engaging in collaborative innovation in 2014–2016. This figure further declined by 10.2 p.p. in 2017–2019 and by 8.3 p.p. in 2020–2022. The likelihood of cooperation increased with enterprise size. Among large enterprises, nearly 51% engaged in innovation cooperation in 2014–2016. However, this figure declined by 7.4 p.p. in 2017–2019 and by 0.5 p.p. in 2020–2022.

Similar trends in innovation-related collaboration were observed in the services sector. The most favorable period was between 2014 and 2016, when nearly 27% of innovatively active service companies engaged in cooperation. However, in the following years, this share declined by 8.4 percentage points and then by an additional 4.7 percentage points. A similar pattern was evident across service enterprises of different sizes, with small companies showing the lowest levels of collaboration and large enterprises the highest.

Between 2014 and 2016, in the industrial sector, companies that were actively engaged in innovation and cooperated with business entities in this field exhibited varying levels of collaboration depending on their industry. The highest levels of cooperation were seen among enterprises producing tobacco products, other transport equipment, and coke and refined petroleum products, where collaboration rates reached 60.0%, 59.3%, and 57.1%, respectively. In contrast, companies involved in furniture production, leather and leather products, and clothing manufacturing had the lowest levels of innovation-related cooperation, with rates of 16.1%, 15.4%, and 4.9% (GUS, 2017, pp. 87–88). A similar distribution was observed in the services sector during the same period 2014–2016, where enterprises in air transport, film and TV production, and scientific research and development demonstrated the highest levels of cooperation. In these industries, all air transport enterprises participated in innovation-related collaboration, while 66.7% of film and TV production companies and 59.6% of research and development firms engaged in such activities. On the other end of the spectrum, businesses involved in publishing, postal and courier services, and land and pipeline transport had the lowest levels of collaboration, with rates of 17.7%, 9.1%, and 8.0%, respectively (GUS, 2017, pp. 87–88).

Between 2017 and 2019, industrial enterprises exhibited significant variation in their engagement in innovation-related collaboration. The highest levels of cooperation were recorded in metal ore mining, where all innovatively active companies collaborated with other enterprises or institutions. Similarly, in the mining of hard coal and lignite, 60% of companies engaged in innovation-related cooperation, while 44.4% of enterprises producing coke and refined petroleum products did the same. The lowest levels of collaboration were observed in food product manufacturing, where only 14.2% of businesses participated, as well as in water collection, treatment, and supply at 13.8%, and furniture production at 13.5% (GUS, 2020, pp. 77–78). In the services sector during the same period, 2017–2019, scientific research and development remained the area with the highest prevalence of innovation cooperation, with nearly 59.7% of firms in this field engaging in such activities. Companies in architecture and engineering, as well as those involved in technical research and analysis, also showed significant collaboration, with 32.3% participating in innovation-related partnerships. Telecommunications companies followed, with 29.2% engaging in cooperation. In contrast, businesses in postal and courier services, warehousing, and transport support services demonstrated the lowest levels of participation, with cooperation rates of 5.6%, 4.2%, and 2.2%, respectively (GUS, 2020, pp. 77–78).

During the 2020–2022 period, in turn, innovation cooperation among industrial enterprises was most common in tobacco product manufacturing and the mining of hard coal and lignite, where 66.7% of innovatively active companies engaged in collaboration. The production of other transport equipment also exhibited a high level of cooperation, with 49.7% of enterprises in this sector participating. However, cooperation was much less common in industries such as wood, cork, straw, and wicker product manufacturing, where only 13.1% of firms engaged in collaborative innovation efforts. Similarly, clothing production had a cooperation rate of 12.5%, while reclamation activities showed the lowest level of engagement at just 10.0% (GUS, 2023, p. 77). In the services sector during the same period, scientific research and development remained the dominant area for innovation-related collaboration, with 65.6% of innovatively active organizations participating. Other sectors also demonstrated considerable cooperation, including insurance, reinsurance, and pension funds, where 41.1% of companies engaged in innovation partnerships, as well as architecture and engineering, where 33.6% collaborated. On the lower end of the spectrum, postal and courier services had a cooperation rate of 17.2%, land and pipeline transport had 12.9%, and water transport had the lowest level of participation at just 11.1% (GUS, 2023, p. 78).

In terms of geographical distribution, between 2014 and 2016 the highest percentage of industrial enterprises engaged in innovation cooperation was recorded in the Podkarpackie (41.4% of innovatively active companies), Śląskie (38.5%), and Małopolskie (38.1%) provinces. In contrast, the lowest levels of cooperation were observed in the Wielkopolskie (29.2%), Zachodniopomorskie (28.6%), and Lubuskie (27.1%) provinces. In the services sector during the same period, innovation-related collaboration was most common among enterprises in the Podkarpackie (73.4%), Warmińsko-Mazurskie (46.2%), and Świętokrzyskie (40.7%) provinces. On the other end of the spectrum, the lowest levels of cooperation were recorded in Łódzkie (14.9%), Opolskie (8.3%), and Lubelskie (7.3%) (GUS, 2017, p. 89).

In the 2017–2019 period, in turn, the pattern changed slightly for industrial enterprises, with the highest levels of innovation cooperation occurring in Lubelskie (29.2%), Śląskie (28.2%), and Opolskie (27.7%). The lowest rates were observed in Podlaskie (19.0%), Zachodniopomorskie (18.9%), and Warmińsko-Mazurskie (13.7%). For service enterprises during the same period, the highest levels of collaboration were recorded in Podkarpackie (39.7%), Łódzkie (31.8%), and Lubuskie (26.7%). In contrast, the lowest levels of cooperation were found in Podlaskie (10.0%), Wielkopolskie (7.4%), and Zachodniopomorskie (2.7%) (GUS, 2020, p. 79).

During 2020–2022, the territorial distribution of innovation cooperation changed once again. Among industrial enterprises, the highest prevalence was recorded in Kujawsko-Pomorskie (34.5%), Opolskie (30.1%), and Podlaskie (29.2%), while the lowest rates were seen in Łódzkie (18.8%), Świętokrzyskie (18.2%), and Warmińsko-Mazurskie (17.8%). In the services sector during the same period, the highest levels of cooperation in innovation were found in Zachodniopomorskie (48.5%), Podkarpackie (40.8%), and Lubuskie (35.5%), whereas the lowest levels were recorded in Opolskie (8.3%), Podlaskie (8.2%), and Kujawsko-Pomorskie (7.1%) (GUS, 2023, p. 79).

Analyzing innovation cooperation by technological level, it is evident that in the industrial processing sector, high-tech enterprises were the most engaged in collaboration, while low-tech enterprises showed the lowest participation. Between 2014 and 2016, innovation cooperation was undertaken by 46.7% of high-tech companies, compared to just 2.2% of low-tech firms (GUS, 2017, p. 90). A similar pattern persisted in 2017–2019, with 33.9% of high-tech enterprises engaging in cooperation, while low-tech firms exhibited a significantly lower rate of 14.6% (GUS, 2020, p. 80). Between 2020 and 2022, the trend remained consistent, with 36.4% of high-tech enterprises participating in innovation-related collaboration, compared to 20.2% of low-tech firms (GUS, 2023, p. 80).

3) Cooperation partners of enterprises in the field of innovative activities

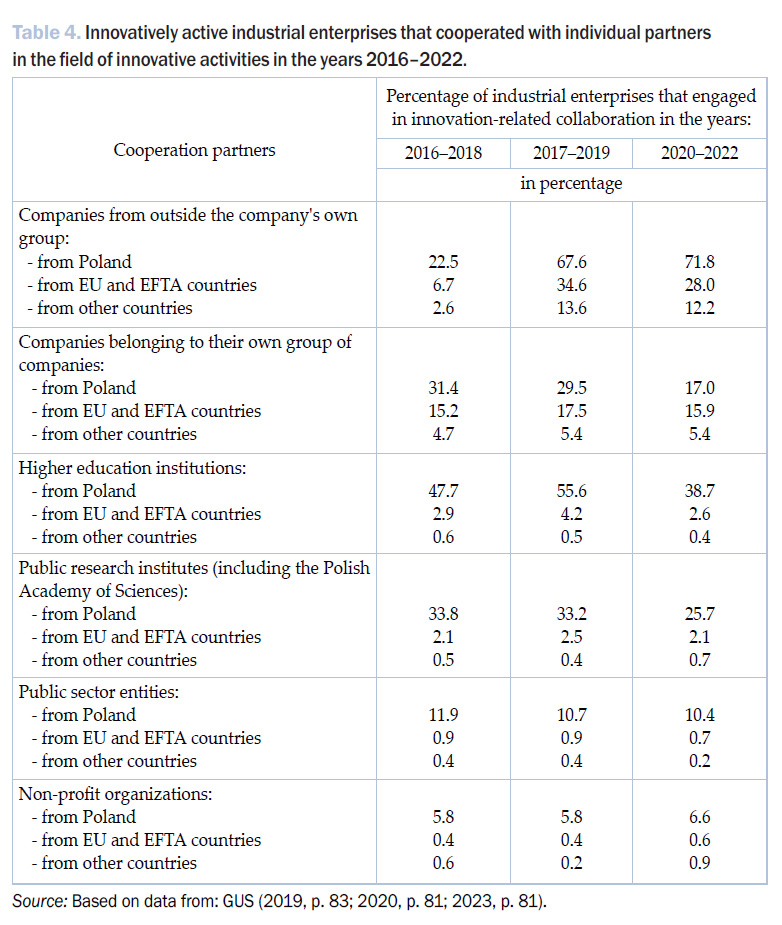

Now that we know that Polish enterprises engaged in innovation-related collaboration, the next important question arises: Who were their key cooperation partners? Table 4 provides a detailed breakdown of these partnerships.

Among industrially active enterprises, collaboration with Polish universities was the most common. Between 2016 and 2018, nearly 48% of industrial enterprises cooperated with universities in Poland. This percentage increased to 56% between 2017 and 2019, before declining to 39% in 2020–2022. Collaboration with foreign universities was significantly less frequent. On average, 3.2% of industrial enterprises cooperated with universities in the EU and EFTA countries, while only 0.5% partnered with universities outside these regions.

Industrial enterprises also collaborated with public research institutes (including those of the Polish Academy of Sciences). Most often these were domestic Polish institutes. In the years 2016–2022, on average, less than 31% of innovatively active companies engaged in such cooperation. There were also cases, albeit rare, of cooperation with foreign institutes. On average, about 2.2% of industrial enterprises cooperated with institutes from the EU and EFTA countries in the analyzed period. On the other hand, about 0.5% of companies in the industrial sector undertook such cooperation with institutes in other countries.

Another common type of cooperation partner was companies belonging to the same group of companies. Most often these were domestic Polish companies, with which almost 26% of enterprises cooperated on average. Some enterprises also collaborated with affiliates from the EU and EFTA countries (16.2%) and from other countries (5.2%).

Industrial enterprises also cooperated with companies from outside their own group of enterprises. In this respect, domestic companies were preferred, with about 54% of industrial enterprises choosing Polish firms as cooperation partners. Meanwhile, 23.1% of partnerships involved EU and EFTA-based firms, and 9.5% involved companies from other countries.

Public sector entities also played a role in innovation cooperation, though at a smaller scale. On average, 11% of industrial enterprises collaborated with Polish public sector units, while partnerships with public sector entities from EU and EFTA countries involved only 0.83% of companies. Cooperation with public sector organizations outside these regions was rare, with only 0.33% of industrial enterprises reporting such collaborations.

Non-profit organizations accounted for a small share of innovation cooperation. In 6.1% of cases, Polish non-profits were cooperation partners for industrial enterprises. Cooperation with EU and EFTA-based organizations was recorded in 0.46% of cases, while 0.56% of partnerships involved non-profits from other countries.

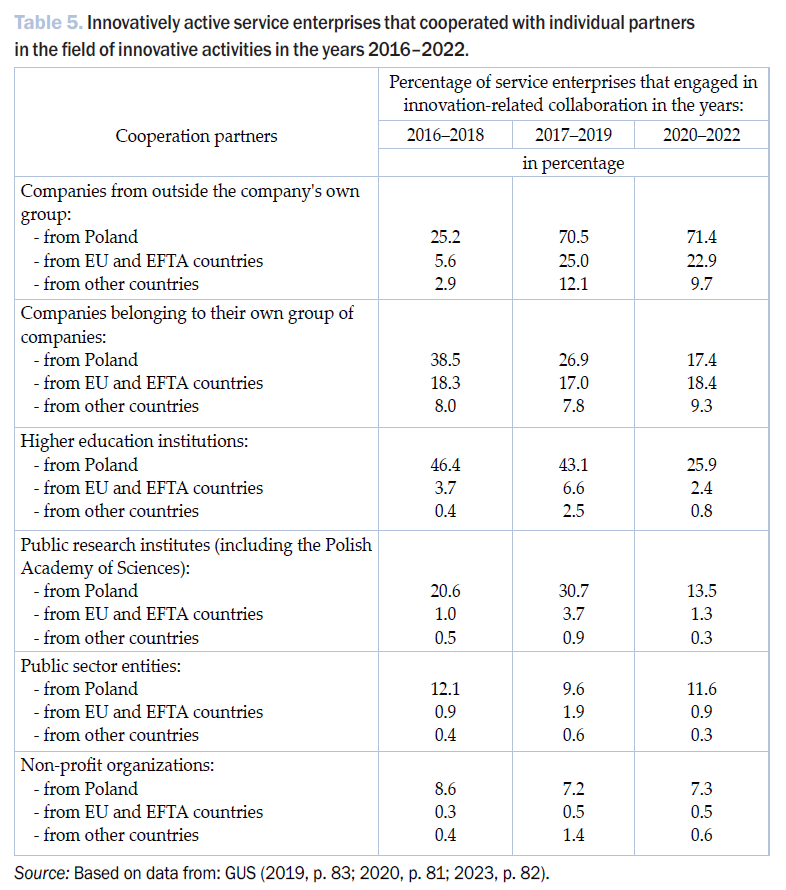

In the service sector, the prevalence patterns of collaboration followed a similar trend. As seen in Table 5, service enterprises most frequently partnered with Polish firms from outside their corporate group. Between 2016 and 2018, only one in four innovatively active service enterprises engaged in such cooperation. However, this figure rose significantly in the following years, exceeding 70% in the 2020–2022 period.

A significant percentage of innovatively active service companies engaged in collaboration with Polish universities. However, this collaboration declined over time, decreasing from 46.4% in 2016–2018 to 43.1% in 2017–2019, and further dropping to 25.9% in 2020–2022. Cooperation with foreign universities remained limited, with only a small percentage of service enterprises establishing partnerships outside Poland. Service enterprises also collaborated with companies within their own corporate group, particularly those based in Poland. On average, 27.6% of service enterprises partnered with domestic companies from within their group, while 17.9% collaborated with firms from EU and EFTA countries, and 8.4% engaged in partnerships with companies from other regions. Collaboration with public research institutes, including those affiliated with the Polish Academy of Sciences, was another avenue for innovation-related cooperation. On average, 21.6% of service enterprises worked with Polish public research institutes, though partnerships with foreign institutions remained minimal. A smaller proportion of service enterprises partnered with public sector entities and non-profit organizations. On average, 11.1% of service enterprises collaborated with Polish public sector institutions, while 7.7% partnered with non-profits in the field of innovation.

4) Companies cooperating within the cluster initiative

One form that innovation-related collaboration among enterprises my take is participation in cluster initiatives. A cluster is a network that harnesses the innovative and organizational potential of a regional environment, supporting intellectual capital accumulation and its efficient utilization. (Encyclopedia.com, n.d.). This structure fits well into the modern innovation paradigm, emphasizing systematicity, holism, and interactivity. Clusters combine the flexibility of small businesses with the innovation and global reach of large enterprises, creating a network where businesses collaborate with the local community cooperates with the companies: state institutions, R&D centers, standardization bodies, quality control laboratories and universities, and even industry, political and cultural organizations.

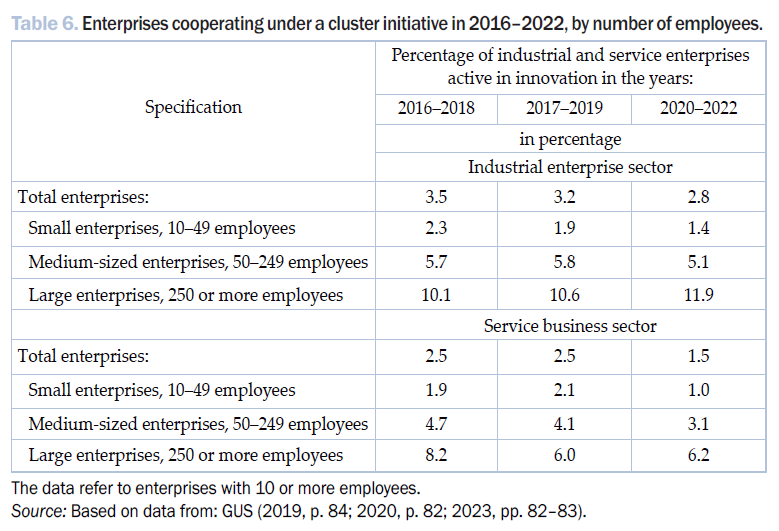

The key question here is: To what extent did Polish companies take advantage of these opportunities? As shown in Table 6, between 2016 and 2018, only 3.5% of industrial enterprises participated in cluster initiatives. This figure declined to 3.2% in 2017–2019 and further dropped to 2.8% in 2020–2022.

In terms of enterprise size, large industrial companies demonstrated the greatest interest in cluster-based cooperation, with an average participation rate of 10.87% over the analyzed period. This figure showed an upward trend, indicating increasing involvement. In contrast, small industrial enterprises were far less engaged, with their participation rate averaging only 1.9%. Among service enterprises, in turn, only 2.2% of companies, on average, engaged in cluster cooperation. Large service enterprises participated the most, while small enterprises showed the least interest in this form of collaboration.

In terms of geographical distribution, in 2016–2018, the highest levels of industrial cluster cooperation were observed for industrial companies in the Lubelskie (8.1%) and Podkarpackie (7.6%) provinces. Meanwhile, the lowest levels were recorded in Opolskie (1.1%) and Wielkopolskie (2.0%). For service enterprises, the highest rates of participation were in Świętokrzyskie (6.6%) and Lubelskie (4.1%), whereas in Opolskie, no companies were recorded as participating in cluster initiatives during this period (GUS, 2019, p. 84).

By 2020–2022, the highest levels of cluster cooperation among industrial enterprises were in Podlaskie (6.3%) and Lubelskie (4.9%), while the lowest levels were recorded in Łódzkie (1.0%) and Lubuskie (1.6%). Among service enterprises, Lower Silesia (3.1%) and West Pomeranian (2.5%) recorded the highest levels of cooperation in this period, whereas Świętokrzyskie (0.5%) and Opolskie (0.6%) had the lowest (GUS, 2023, pp. 83–84).

Broken down by industry, between 2016 and 2018, cluster participation was highest among industrial companies engaged in hard coal and lignite mining (18.2%) and metal ore mining (16.7%). On the other hand, industries such as paper and paper product manufacturing and textile production had the lowest rates of participation, at only 1.2% each (GUS, 2019, pp. 86–87). By 2020–2022, the highest cluster participation in the industrial sector was recorded in the production of other transport equipment (12.5%), while no companies in the tobacco or clothing manufacturing sectors participated in cluster initiatives.

In the service sector, the highest level of cluster participation between 2016 and 2018 was found in scientific R&D (17.1%) and air transport (13.6%). In contrast, wholesale trade (1.5%) and land and pipeline transport (0.9%) had the lowest levels of participation. By 2020–2022, the research and development sector remained the most active in cluster initiatives, with 21.7% of enterprises engaged. However, in the water transport sector, no companies were recorded as participating in cluster cooperation (GUS, 2023, pp. 83–84).

More broadly, the statistical data presented in this paper indicate a certain regularity: industrial enterprises engaged in high-technology activities were the most likely to participate in cluster initiatives, with an average participation rate of 10.8%. Conversely, companies operating in low-technology industries had the lowest participation rate, at only 1.2% (GUS, 2023, p. 87).

4. Conclusions

The primary aims of this study were: 1) to analyze the prevalence of innovative activity among Polish industrial and service enterprises and, in this context, the prevalence of their innovation-related collaboration with other business entities, 2) to critically assess the extent of Polish enterprises’ innovation-related collaboration, demonstrating that such collaboration has occupied only a rather marginal place the managerial decision-making processes.

To achieve these goals, key measures were used to assess both innovation activity and innovation-related collaboration. These measures, outlined in six tables, were critically analyzed, resulting in the following key conclusions:

- The share of innovative enterprises in the total number of businesses, both industrial and service-based, fluctuated across the years analyzed, without showing a clear upward trend.

- The percentage of industrial enterprises engaged in innovation-related cooperation varied randomly over time and never exceeded 9.1% during the analyzed period.

- Although the share of industrial enterprises participating in formalized cooperation structures was slightly higher, it remained inconsistent over time.

- The percentage of innovatively active enterprises was slightly higher in the industrial sector than in the service sector. In both sectors, larger enterprises exhibited higher levels of innovative activity compared to smaller ones.

- Cooperation in innovation activities was slightly more common in the industrial sector than in the service sector. Even during the most favorable period (2014–2016), cooperation rates did not exceed 33% in industry and 27% in services, and in subsequent periods, they were even lower. This suggests that decision-making processes related to innovation cooperation were highly inconsistent. Larger enterprises had a significantly higher level of participation, while small enterprises remained the least engaged.

- When comparing innovation cooperation rates in Poland with those in other European countries, Poland ranked relatively low. In 2018–2020, 23.6% of industrial enterprises in Poland cooperated in innovation, whereas in Norway, this rate was 53.8%. Similarly, in the services sector, the Polish cooperation rate was 20.9%, compared to 43.2% in Cyprus (GUS, 2023, p. 87). Earlier data from 2016–2018 showed similarly unfavorable trends (GUS, 2020, p. 86). In 2020, the EU average for innovation cooperation stood at 25.7%, while in Poland, it was 22.4%, 3.3 percentage points lower (EUROSTAT 2020a, 2020b).

- Both industrial and service companies undertook limited innovation-related collaboration with various partners. Most often these were: enterprises from outside their own group of enterprises; undertakings belonging to its own group of companies; higher education institutions; public research institutes; public sector entities and non-profit organizations. Collaboration was mainly with domestic partners from Poland, much less often with those from other countries. The low level of strategic organization in these collaborations suggests that cooperation was often ad hoc than systematically managed.

- Cluster initiatives remained an underutilized form of innovation cooperation. The average participation rate was 3.16% for industrial enterprises and 2.16% for service enterprises, with a downward trend in later periods.

The relatively low level of innovation among Polish enterprises appears to stem from a lack of understanding of innovation’s role, its impact on business development, and weak innovation management practices that are not grounded in knowledge-based, research-driven models (Baruk, 2022, pp. 10–23; Baruk, 2021, pp. 14–27). Consequently, innovation activity and innovation-related collaboration remain limited.

Often, employees within companies lack the necessary knowledge to develop systematic or radical innovations. In such cases, it is crucial to access external knowledge through structured collaboration with scientific and economic institutions that possess the necessary expertise or can help co-create it. Therefore, managers must develop competencies in key areas related to innovation, such as knowledge management, strategy, organizational culture, systemic learning, teamwork, and cooperation with business partners and clients.

Effective innovation management should be based on a deep understanding of the impact of innovation on businesses, their employees, and end users. As a result, managers should strive to transform their organizations into leading innovators (Peters & Waterman, 2000, pp. 45–48). Achieving this goal requires implementing structured, research-backed innovation management strategies, as outlined in relevant scientific literature (Baruk, 2022, pp. 10–23; Baruk, 2021, pp. 14–27; Baruk, 2009; Baruk, 2015, pp. 121–145; Tidd & Bessant, 2013).

5. Suggestions for further research

Given the levels of enterprise innovation analyzed in this study, further theoretical and empirical research is warranted to assess the stability or variability of these measures over time. Conducting such an analysis would provide valuable insights into several key questions, including:

- Are trends in enterprise innovation activity consistent over time, and if so, what patterns emerge?

- What are the long-term tendencies in innovation-related cooperation?

- How do these trends evolve dynamically across different periods?

- Which scientific and economic entities are most commonly involved in innovation cooperation?

- How widespread and dynamic is such cooperation across industries and sectors?

- What tangible effects does innovation collaboration have on business performance?

- How do information-sharing and decision-making processes influence the initiation of cooperation?

- Do managers systematically analyze and evaluate innovation activity and collaboration trends?

- Are the findings from these analyses effectively used to improve management processes and decision-making within enterprises?

Addressing these questions would deepen our understanding of innovation ecosystems, help identify barriers and facilitators of collaboration, and provide practical recommendations for improving innovation management strategies in business environments.

References

Alshwayat, D., Elrehail, H., Shehadeh, E., Alsalhi, N., Shamout, M. D., & Ur Rehman, S. (2023). An exploratory examination of the barriers to innovation and change as perceived by senior management. International Journal of Innovation Studies, 7(2), 159–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijis.2022.12.005

Baregheh, A., Rowley, J., & Sambrook, S. (2009). Towards a multidisciplinary definition of innovation. Management Decision, 4(8), 1334. https://doi.org/10.1108/00251740910984578

Baruk, J. (2009). Zarządzanie wiedzą i innowacjami [Management of knowledge and innovations]. Wydawnictwo Adam Marszałek w Toruniu.

Baruk, J. (2011). Wiedza w procesach tworzenia innowacji [Knowledge in the processes of creating innovations]. Organizacja i Kierowanie (4), 113–127.

Baruk, J. (2015). Zarządzanie działalnością innowacyjną w organizacjach naukowych i badawczo-rozwojowych [Managing innovative activities in scientific and research and development organizations]. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 17(3), 121–145; https://doi.org/10.14611/ minib.17.03.2015.04

Baruk, J. (2018). Wiedza i innowacje jako czynniki rozwoju organizacji – Podejście zintegrowane [Knowledge and innovation as factors of organizational development – An integrated approach]. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 29(3), 83–110. https://doi.org/10.14611/minib.29.09.2018.05

Baruk, J. (2021). Wspieranie zarządzania innowacjami rozwiązaniami modelowymi [Supporting innovation management with model solutions]. Marketing i Rynek, XXVIII(3), 14–27. https://doi.org/10.33226/1231-7853.2021.3.2

Baruk, J. (2022). Racjonalizacja zarządzania innowacjami – koncepcje modelowe [Rationalization of innovation management – Model concepts]. Marketing i Rynek, XXIX(5), 10–23. https://doi.org/10.33226/1231-7853.2022.5.2

Baruk, J. (2023). Znaczenie wiedzy w podnoszeniu sprawności działalności innowacyjnej przedsiębiorstw [The importance of knowledge in improving the efficiency of innovative activities of enterprises]. Marketing i Rynek, XXX(6), 43–55. https://doi.org/10.33226/1231-7853.2023.6.5

Brzeziński, M. (ed.). (2001). Zarządzanie innowacjami technicznymi i organizacyjnymi [Management of technical and organizational innovations]. Warszawa, Difin.

Carvache-Franco, O., Carvache-Franco, M., & Carvache-Franco, W. (2022). Barriers to Innovations and Innovative Performance of Companies: A Study from Ecuador. MDPI. Social Science, 11(2), 1–17.

Cowan, K. M., Haralson, L.E., & Weekly, F. (2009). The Four Key Elements of Innovation: Collaboration, Ideation, Implementation and Value Creation. Retrieved July 24, 2024, from https://www.stlouisfed.org/ publications/bridges/summer-2009/the-four-key-elements-of-innovation-collaboration-ideation-implementation-and-value-creation

Das, P., Verburg, R., Verbraeck, A., & Bonebakker, L. (2018). Barriers to innovation within large financial services firms: An in-depth study into disruptive and radical innovation projects at a bank. European Journal of Innovation Management, 21(1), 96–112. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-03-2017-0028

Encyclopedia.com. (n.d.). Clusters. Retrieved July 28, 2024, from https://www.encyclopedia.com/ entrepreneurs/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/clusters

EUROSTAT. (2020a) Enterprises with innovation activities during 2018 and 2020 by NACE Rev. 2 activity and size class (2020). Retrieved July 26, 2024, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/ view/inn_cis12_inact/default/table?lang=en&category=scitech.inn.inn_cis12.inn_cis12_inno

EUROSTAT. (2020b). Innovative enterprises that co-operated on R&D and other innovation activities with other enterprises or organisations, by kind and location of co-operation partner, NACE Rev. 2 activity and size class (2020). Retrieved July 26, 2024, from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/databrowser/ view/inn_cis12_coop/default/table?lang=en&category=scitech.inn.inn_cis12.inn_cis12_inno

GUS. (2017). Działalność innowacyjna przedsiębiorstw w latach 2014-2016 [Innovative activity of enterprises in the years 2014-2016]. Central Statistical Office (GUS). Warszawa, Szczecin.

GUS. (2019). Działalność innowacyjna przedsiębiorstw w latach 2016-2018 [Innovative activity of enterprises in the years 2016-2018]. Central Statistical Office (GUS). Warszawa, Szczecin.

GUS. (2020). Działalność innowacyjna przedsiębiorstw w latach 2017-2019 [Innovative activity of enterprises in the years 2017-2019]. Central Statistical Office (GUS). Warszawa, Szczecin.

GUS. (2023). Działalność innowacyjna przedsiębiorstw w latach 2020-2022 [Innovative activity of enterprises in the years 2020-2022]. Central Statistical Office (GUS). Warszawa, Szczecin.

Hardwick, J., Anderson, A. R., & Cruickshank, D. (2013). Trust formation processes in innovative collaborations. European Journal of Innovation Management, 16(1), 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/ 14601061311292832

Hilmersson F.P. & Hilmersson M. (2021). Networking to accelerate the pace of SME innovations. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 6(1), 43–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061311292832

Indrawati H., Caska, & Suarman. (2020), Barriers to technological innovations of SMEs: how to solve them?, International Journal of Innovation Science, 12(5), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-04-2020-0049

Janasz, W. & Kozioł-Nadolna, K. (2011). Innowacje w Organizacji [Innovations in the Organization]. Warszawa, PWE Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne.

Kowalczyk, A. & Nogalski, B. (2007). Zarządzanie wiedzą. Koncepcje i narzędzia [Managing Knowledge: Concepts and Tools]. Warszawa, Difin.

Kozioł-Nadolna, K. (2022). Przywództwo a innowacyjność organizacji. Perspektywa teoretyczna i praktyczna [Leadership and Organizational Innovativeness: Theoretical and Practical Perspectives]. Warszawa, Difin.

Latif, Y. (2024). Importance of innovation. Retrieved July 26, 2024, from https://www.linkedin.com/ pulse/importance-innovation-yasir-latif-cipm-cipc-v0ed

Lind, F., Styhre, A., & Aaboen, L. (2013). Exploring university-industry collaboration in research centres. European Journal of Innovation Management. 16(1), 70–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601061311292869

Martínez-Azúa, B. C. & Sama-Berrocal, C. (2022). Objectives of and Barriers to Innovation: How Do They Influence the Decision to Innovate? Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity, 8(134), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc8030134

Nonaka, I. & Takeuchi, H. (2000). Kreowanie wiedzy w organizacji [Generating Knowledge in the Organization]. Warszawa, Poltext.

Ordoñez-Gutiérrez A.V., Mendez-Morales A., & Herrera M.M. (2023). Barriers to Innovation: A Systematic Literature Review. Trilogia, Ciencia Tecnología Socieda, 29(15), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.22430/21457778.2614

Peters, T.J. & Waterman, R.H. (2000). Poszukiwanie doskonałości w biznesie [Seeking Excellence in Business]. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo MEDIUM. Polish edition of Peters, T. J., & Waterman, R. H. Jr. (1982). In search of excellence: Lessons from America’s best-run companies. Harper & Row.

Sosnowska, A., Łobejko, S., & Kłopotek, A. (2000). Zarządzanie firmą innowacyjną [Managing an Innovative Firm]. Warszawa, Difin.

Świadek, A. (2021). Krajowy system innowacji 2.0 [The National Innovation System 2.0]. Warszawa, CeDeWu.

Świtalski, W. (2005). Innowacje i konkurencyjność [Innovations and Competitiveness], Warszawa, WUW.

Tidd, J. & Bessant, J. (2013). Zarządzanie innowacjami. Integracja zmian technologicznych, rynkowych i organizacyjnych. Warszawa. Oficyna a Wolters Kluwer Business. Polish edition of Tidd, J. & Bessant, J. (1997), Managing Innovation: Integrating Technological, Market and Organizational Change.

Ullah, I., Hameed, R.M., Mahmood, A. (2024). The impact of proactive personality and psychological capital on innovative work behavior: evidence from software houses of Pakistan, European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(6), 1967–1985. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-01-2022-0022

Watkins, M. (2024). The Power of Collaboration: How an Open Innovation Platform Fuels Your Company’s Success. Retrieved July 25, 2024, from https://www.wazoku.com/blog/open-innovation-crowdsourcing-external-innovation-collaboration/

Wong, J.-Y., Wan, T.-H., & Chen, H.-C. (2018). The innovative grant of university–industry–research cooperation: A case study for Taiwan’s technology development programs. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(3), 316–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-01-2017-0004

Yunus, E. N. (2018). Leveraging supply chain collaboration in pursuing radical innovation. International Journal of Innovation Science, 10(6), 350–370. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJIS-05-2017-0039

Zangara, G. & Filice, L. (2024). Innovating the management of supply chains for social sustainability: from the state of the art to an integrated Framework. European Journal of Innovation Management, 27(9), 360–383. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJIM-02-2024-0120