- eISSN 2353-8414

- Tel.: +48 22 846 00 11 wew. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Aktualność raportów audytowych przed i podczas pandemii COVID-19: na podstawie reakcji rynku

Jesslyn Yen, Antonius Herusetya

Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Lippo Village,

MH Thamrin Boulevard 1100, Klp. Dua, Kec. Klp. Dua, Kota Tangerang, Banten, Indonezja

*E-mail: antonius.herusetya@uph.edu

ORCID: 0000-0002-5649-4578

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0004

Abstrakt:

Niniejsze badanie dotyczy reakcji rynku na terminowość sprawozdań z audytu, w szczególności przed i w trakcie pandemii koronawirusa 2020 (COVID-19). Użyto współczynnik odpowiedzi zysków (ERC) jako wskaźnika zastępczego do oceny reakcji rynku na terminowość raportów z audytu. Zastosowano metodę celowego doboru próby do wszystkich spółek notowanych na Indonezyjskiej Giełdzie Papierów Wartościowych (IDX), z wyjątkiem branży finansowej, i jako ostateczną próbe poddano obserwacji 977 firm. Stosując w analizie modele liniowej regresji wielokrotnej, nie stwierdzono żadnej reakcji rynku na terminowość sprawozdań z kontroli dla pełnej próby w latach 2018–2020. Wskazano jednak dowody na to, że podczas pandemii COVID-19 w 2020 r. rynek reagował bardziej pozytywnie na terminowość raportu z audytu w porównaniu z okresem przed pandemii COVID-19. Uzyskane wyniki potwierdzaja, że inwestorzy wykazywali większą tolerancję wobec opóźnionych raportów audytowych podczas pandemii koronawirusa z uwagi na wzrost wysiłku audytowego i dłuższego czasu potrzebnego do zgromadzenia wystarczajcych dowodów, aby opublikować raporty audytowe.

MINIB, 2023, Vol. 47, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0004

Str. 49-70

Opublikowano 31 marca 2023

Aktualność raportów audytowych przed i podczas pandemii COVID-19: na podstawie reakcji rynku

Introduction

The duality of marketing manifests itself in the necessity for a synergistic combination of different approaches: quantitative and qualitative, strategic and operative, analytic and creative, and others. Although the need for a broader qualitative approach in reference to social sciences is indicated (Czarniawska, 2021), this does not mean any reduced need for rigour and methodological diligence in the activities carried out in the sphere of science and practice. As a result, the idea of evidence-based management (EBM) was created at the turn of the 20th century. The key assumption underlying EBM is that a given organisation is constantly striving to increase the reliability of the evidence employed in all its decision-making processes, and thus the value of recommendations put forward based on such evidence. Marketing indicators are a significant element constituting the measurement of market activities and the quality of decisions on one side and, on the other, the anchorage of marketing activity in the concept of evidence-based marketing. This article aims to identify the extent of employment of marketing indicators on the Polish market as an element of evidence-based marketing. Consequently, the research results presented provide business practitioners with the possibility to benchmark their actions against those of other organisations on the Polish market based on evidence regarding the use of individual marketing indicators presented in the article. The starting point for the deliberations included in the article is determining the essence of EBM and referring it to the field of marketing, while the empirical basis is provided by the research conducted in November 2022 among the participants and graduates of programmes of the Chartered Institute of Marketing (CIM).

Evidence-Based Management — Essence, Characteristics, Process

The concept of EBM was born as a result of discontentment with low quality of the research conducted and cognitive biases leading to decisions that were frequently misguided. It stems from the so-called 'evidence-based practice (EBP)’, which was started in the medical sector, and the fear of making wrong decisions and formulating inappropriate medical recommendations (Mulrow, 1987; Antman, Lau, Kupelnick, Mosteller, & Chalmers, 1992; Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997). Instead, it was postulated to base them on reliable facts, evidence and research results (Tranfield, Denyer, & Smart, 2003).

The positive effects of EBP led to it being implemented in other fields — first, in management (Denyer & Neely, 2004) and, later, in marketing (Rowley, 2012; Sharp, Wright, Kennedy, & Nguyen, 2017). In the field of social sciences, another contribution to the development of EBM was the poor quality of scientific publications — what was criticised first and foremost was the poor quality of research, a lack of sufficient clarity of recommendations and a significant degree of abstraction (Wind & Nueno, 1998; Pfeffer & Sutton, 1999; Aram & Salipante, 2000; Hodgkinson, Herriot, & Anderson, 2001), leading to the inadequacy of the theoretical sphere concerning the business practice (Tranfield, Denyer, Marcos, & Burr, 2004; Brennan, 2008).

EBM can, thus, be defined as a business decision-making process relying on adequate and reliable data and the best evidence available, all obtained from a diversified base of sources (Barends & Rousseau, 2018). This means that EBM attempts, on one hand, to combine theory and practice and, on the other, to increase the effectiveness of managers within the scope of decisions they make. Thus, EBM constitutes an inseparable part of the knowledge-based economy (Rowley, 2012).

EBM corresponds to the theory of praxeology (Kotarbiński, 1973), which represents a similar approach to objectives, perception of an organisation and research methods — the existence of numerous sources, diligence and critical evaluation, a multilateral approach and a method of conducting analysis and synthesis (Szpanderski, 2008). Its aftermath consists of trends such as business performance management (Eckerson, 2005) or business intelligence (Radziszewski, 2016), which combine quantitative and qualitative research, thus striving to evaluate market results and discover the dependencies between the organisation and its environment is consistent at the same time with triangulation principles. It has been proved that taking advantage of many sources supported by their critical evaluation-including taking advantage of the experience and knowledge of many people (Armstrong, 2001; Silver, 2012) and 'hard data’ (Lewis, 2004; Grove, 2005) — and then aggregating the results obtained is more effective than relying on single sources and leads to making more accurate decisions (McNees, 1990; Tetlock, 2006).

At the same time, EBM separates itself from the intuitive approach in favour of the so-called ’empirical generalisation’ (Kozielski, 2022). Empirical generalisation presents the causal relationships and dependencies between the methods, instruments and actions and the reaction of buyers and the degree of influence on their decisions through universal laws regarding varied aspects of the market activity of an organisation (Wind & Sharp, 2009) obtained in a rigorous research process conducted in different contexts and generating coherent conclusions and recommendations (Shaw & Merrick, 2005).

As has been indicated, EBM is mainly based on evidence — research results, information, facts or data that either support the assumptions or hypotheses or reject them. The knowledge and experience of managers and experts are included among these, as well as the indicators and metrics (Barends & Rousseau, 2018). Meanwhile, evidence can be characterised by three fundamental features:

1. validity — understood as the integrity of data and conclusions stemming from them;

2. reliability — understood as the degree of probability that another measurement conducted using the same method will yield similar results

(Bryman & Bell, 2012); and

3. bias — understood as the possibility of influence of factors distorting the research process (Longbottom & Lawson, 2017).

EBM as a method of improving the organisation’s functioning and the related accuracy and quality of business decisions made is consistent with marketing-or, more broadly, management-entering the era of measurement and data (Provost & Fawcett, 2013; Chavez, O’Hara, & Vaidya, 2018), and consequently, the era of a market decision made based on adequate and relevant data. The knowledge of changes taking place in the organisation’s environment and-further on-conscious use of information has a positive impact on the correlation between the objectives and activities of an organisation, similar to the transparency within the scope of data and evidence employed or the responsibility of a manager for the decision made based on such data and evidence (LaPointe, 2005). This enables discovering market laws and making more effective decisions, which leads to more efficient competition and the formation of resilient organisations (Kozielski, 2022). The characteristics of EBM and evidence-based marketing can be contained within three key conclusions constituting the essence of these concepts:

1. EBM is based on sound and meticulously conducted research and a comprehensive and systematic approach to data and information gathering, which aims to produce the best and most up-to-date market knowledge, resulting in effective managerial decision-making, a better understanding of the market and buyers and building competitive advantage and a customer-centric and resilient organisation;

2. EBM has a practical and application character and forms a bridge connecting the sphere of science with management practice; and

3. EBM is characterised by procedures aimed at obtaining diligent knowledge and combining science with practice (Kozielski, 2022).

EBM, and especially marketing measurement, refers in its assumptions to an organisation’s efficiency and productivity. The beginnings of this trend in management science can already be found in the source literature from over 100 years ago (Taylor, 1911). However, the dynamic growth of research and publications in the field of measurement of marketing activities and results dates back to the first years of the 21st century (Shaw & Merrick, 2005; McDonald, Smith, & Ward, 2007). The possibilities of taking advantage of marketing indicators have been addressed, to the most comprehensive extent, in the studies of Davis (2007) and Farris et al. (2010)This was related to the development of digital marketing and extensive access to data — especially real-time data (Sterne, 2002; Heman & Burbary, 2013).

The development of measurement based on marketing indicators, especially those acquired in a dynamic way, was mainly due to dissatisfaction with the use of traditional metrics, which were largely historical, retrospective, focussed on financial aspects, had little reflection and translation into the organisation’s market strategy, etc. At the same time, the importance of intangible assets in an organisation was growing and the ideas of value-based marketing and learning or agile organisations were developing. All of this has led to an intensification of the use of marketing indicators in organisations over the past decade or so and to an expansion of their use, particularly in relation to the digital sphere — internet marketing, e-commerce, social media, etc. (Kozielski, 2015). The question naturally arises as to the current extent of the use of marketing indicators functioning on the Polish market.

Research Methodology

EBM is determined by the indicated key features and conditions of its course. This applies to market activities in particular. An immanent element in the sphere of marketing is the measurement of effects and marketing actions and the marketing indicators obtained as a result of it. In view of the above, the survey aimed to assess the extent to which marketing managers use marketing indicators and to identify the specifics of these metrics on the Polish market.

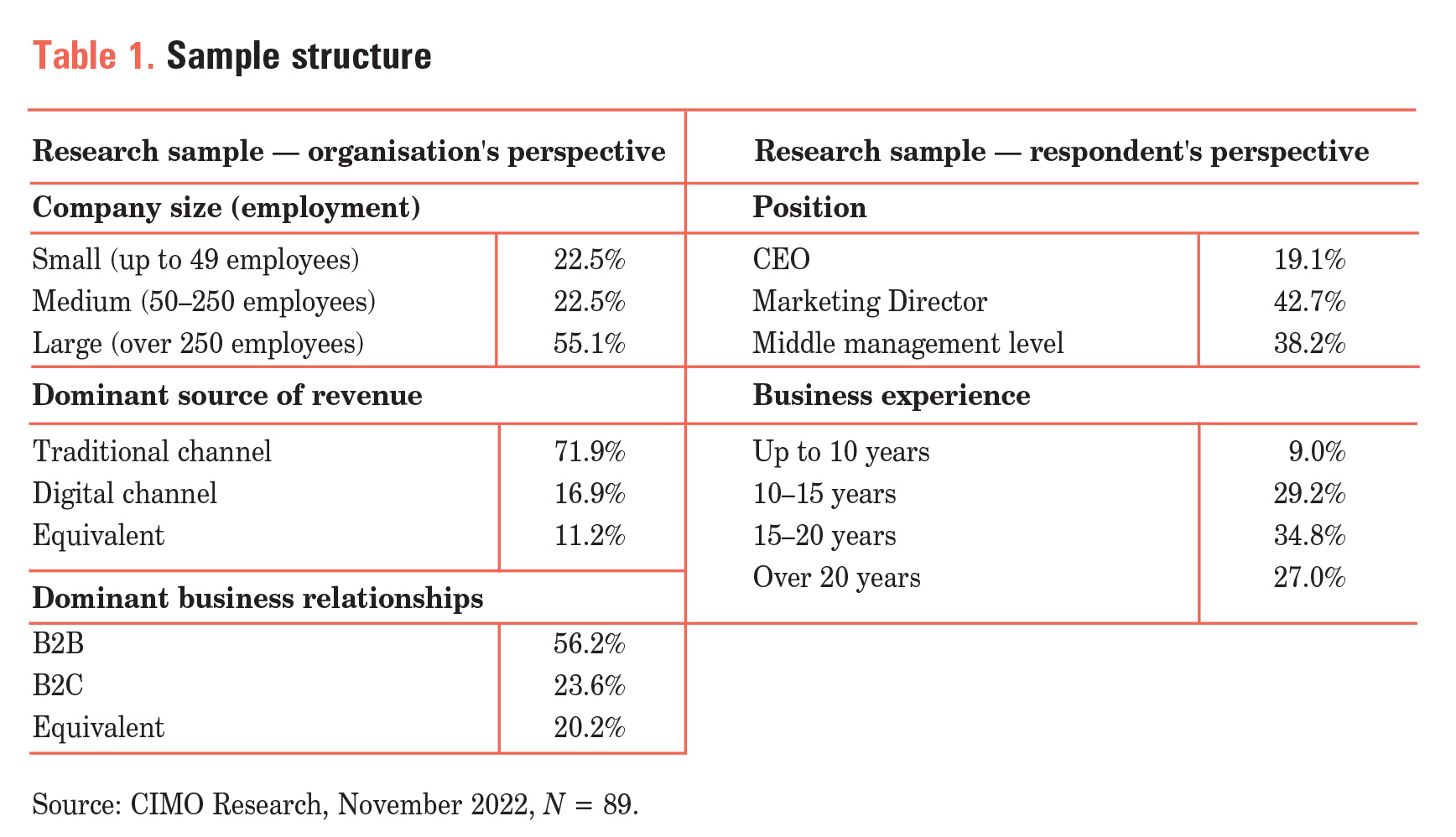

The empirical basis was provided by the 'CIMO Standards & Foresight’ research project carried out on the Polish market. The survey was conducted in November 2022 using the CAWI method on a group of Polish graduates of the CIM having certified professional qualifications. The survey participants were comprised of 89 respondents, who were chosen based on purposeful sampling. The selection criteria were: experience in marketing and position occupied (CEO, director, middle manager). The idea behind the selection was for each person surveyed to represent a different organisation. Therefore, from this point of view, the size of the company, the dominant source of revenue and the type of business relationships were chosen as the selection criteria. The research sample is shown in Table 1. The survey instrument was an interview questionnaire which, in the part corresponding to the results presented in the article, consisted of a number of questions on the indicators used (semi-closed questions) and the frequency of using them.

Use of Marketing Indicators in Poland

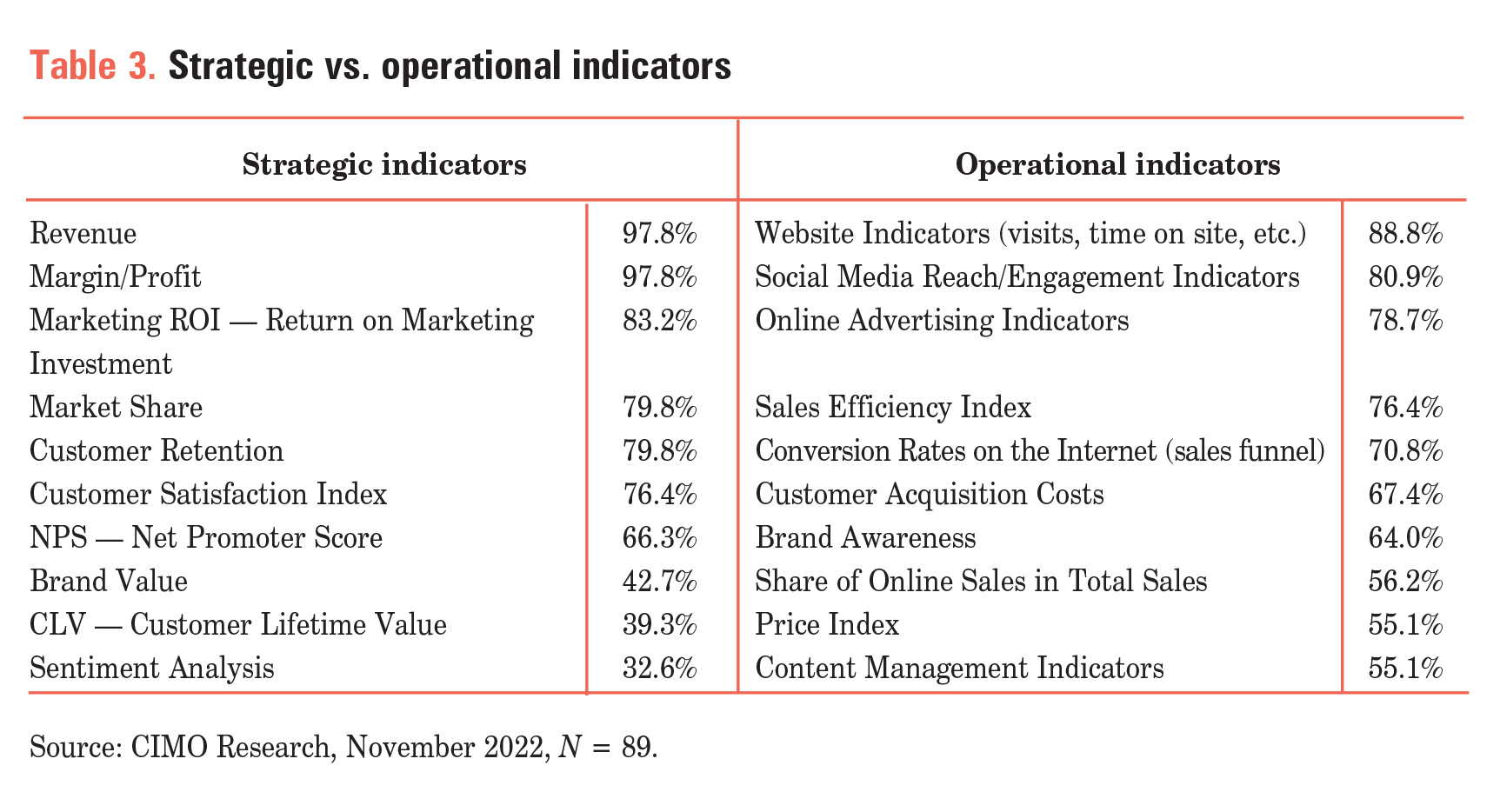

Adopting an EBM formula requires, among other things, the use of diverse sources of information, indicators that give a complete picture of the market situation and metrics that allow effective decisions to be made at strategic and operational levels. According to the research, three areas of measurement come to the fore among the indicators employed on the Polish market (Table 2). The first is related to the financial sphere (revenue, margin/profit), the second to market position and market activity (market share, customer retention, customer satisfaction) and the third to digital activity (visits, reach, engagement and conversion indicators in relation to websites, social media and online advertising). It could be argued that such a mix is quite balanced and touches upon both the strategic and operational spheres. At the same time, however, it should be pointed out that the marketing indicators used by marketers are wellknown and fairly standard in nature, and some of them are traditional metrics of market activity.

On the other hand, among the indicators that marketers on the Polish market least use are those relating to influencer marketing, sentiment analysis, the share of wallet, CLV and GRP indicators and distribution metrics. These indicators are also applied to various areas of the organisation’s activity (offline vs. online, financial vs. non-financial). Obviously, the analysis of the indicator application scope alone is insufficient to draw far-reaching conclusions. Hence, looking at these indicators from a strategic, operational and frequency-of-use perspective is useful.

The analysis of marketers’ declarations as to the strategic and operational indicators used (Table 3) confirms the previously formulated conclusion regarding the noticeable balance between these two categories of metrics. It seems that such an approach should be viewed positively and may also stem from the fact that both middle and senior management participated in the research. In the case of strategic indicators, sales and profitability measurement again comes to the fore, followed by marketing effectiveness (ROMI), company/brand positioning (market share, brand value) or indicators related to customer retention (retention, satisfaction, CLV). In the area of operational indicators, on the other hand, marketers tend to measure the area of digital marketing and, again, sales. They take the different stages of the purchase process defined in models into account, such as the customer journey (Lemon & Verhoef, 2016) or the RACE model (Chaffey & Ellis-Chadwick, 2019) — from reaching the customer (e.g. social media reach, website hits, online advertising and brand awareness) and establishing interaction (e.g. time on site and content management) through conversion (e.g. sales effectiveness, conversion and customer acquisition cost), to maintaining engagement (e.g. social media engagement and content management).

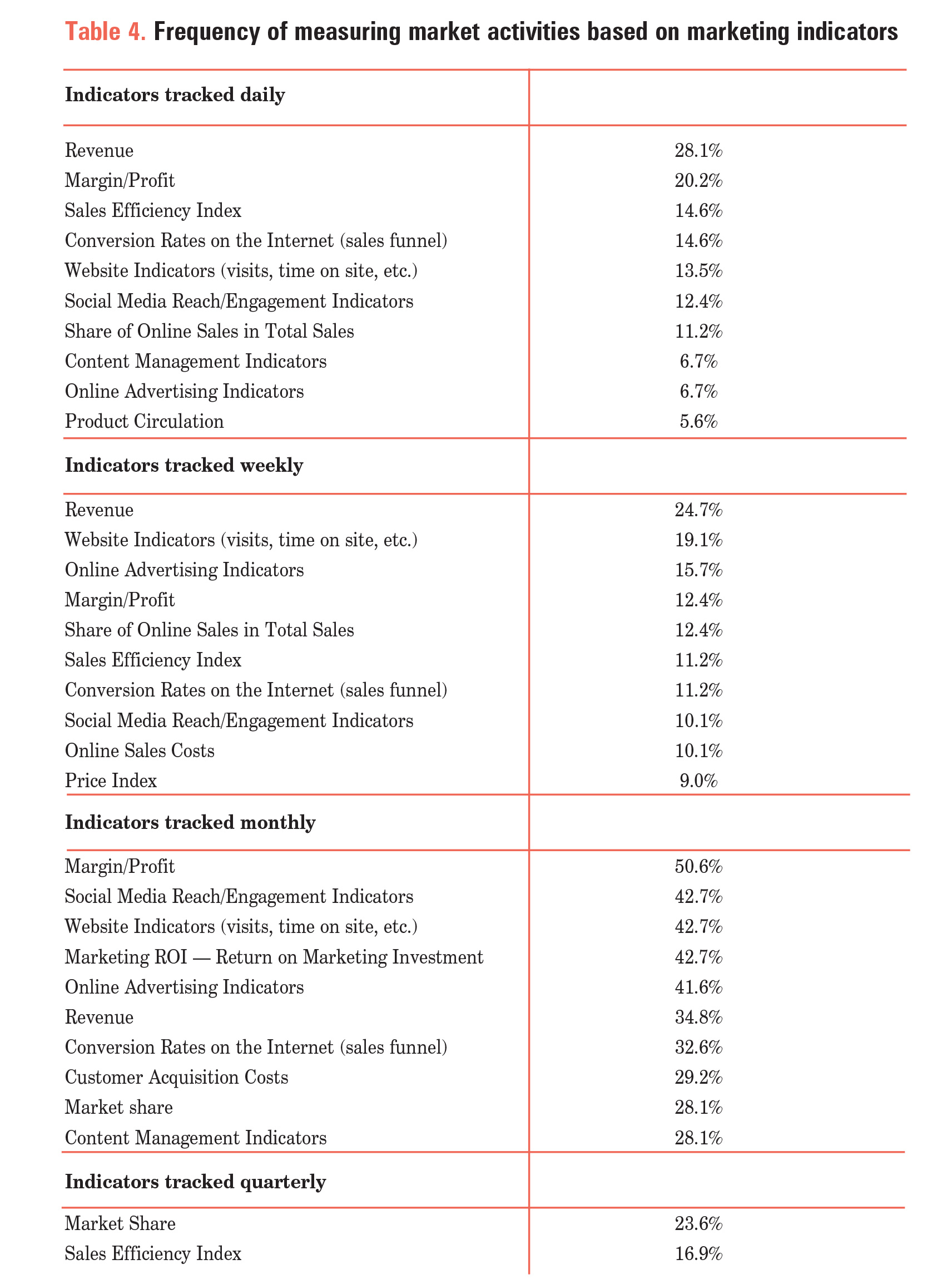

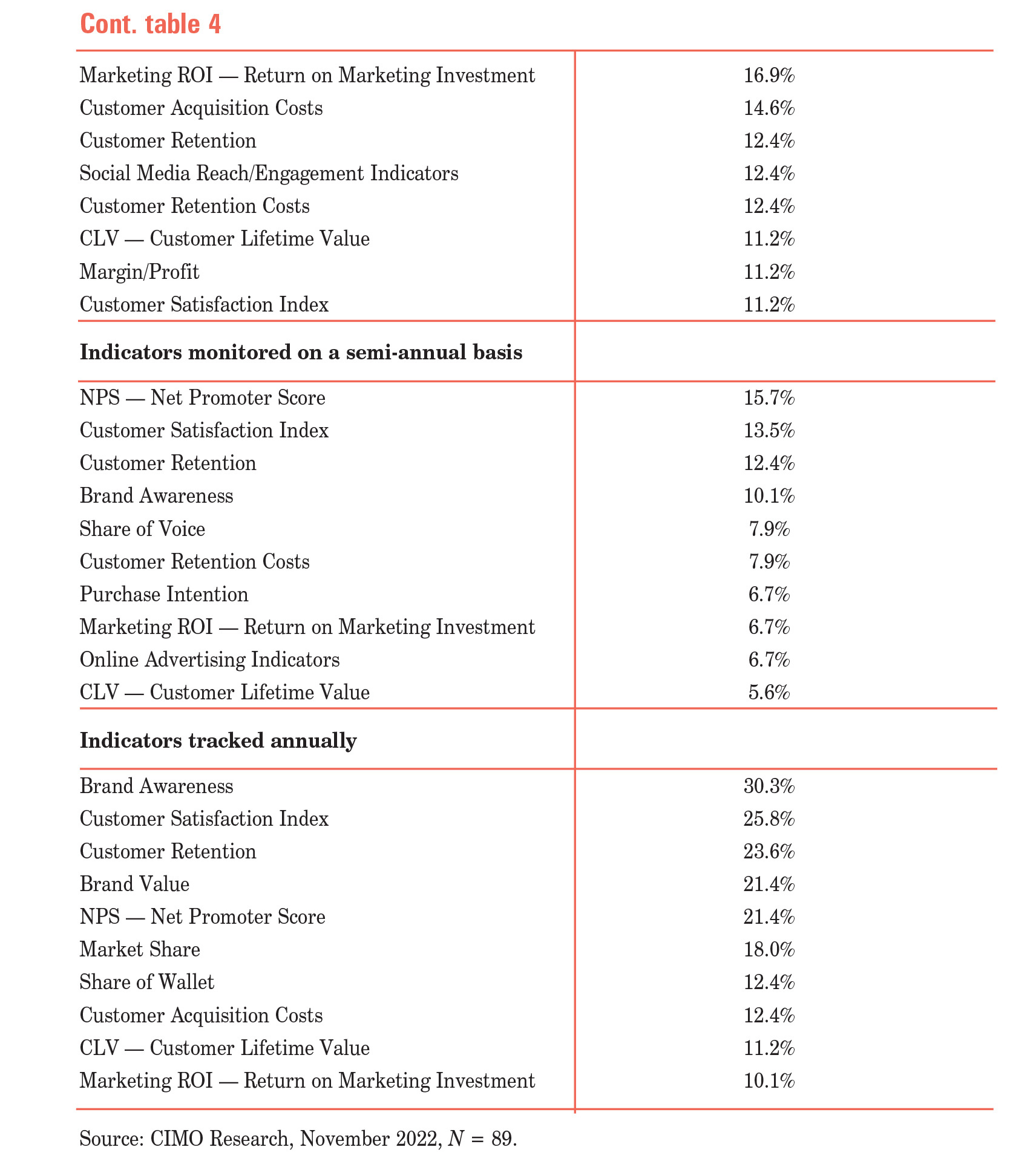

The survey also took into account the identification of the frequency of the measurements carried out (Table 4). It showed that Polish marketers are most likely to measure on a monthly basis. This is where the highest total indications were recorded. The second quite typical frequency of marketing activity monitoring in Poland is annual monitoring. When looking at all the separate measurement periods, it is possible to find that there is not much differentiation in terms of defined categories (offline vs. online, financial vs. non-financial). As indicated earlier, a balanced mix of metrics-strategic and operational, traditional and more modern, etc.-dominates across all adopted measurement frequencies. The only clear trend is that the less frequent measurements and assessments (semi-annual and annual measurements) are dominated by those more strongly related to marketing, marketing-built assets and market activities — NPS, brand awareness and value, customer satisfaction, market share, customer retention, etc. It is also worth noting that strategic indicators are undeniably monitored much more frequently on an annual basis than operational ones.

Summary

EBM relies on the assumption of using adequate, diligent data from the best available sources, collected in a way that ensures its credibility (diligence and accuracy). In the marketing sphere, this applies-in particular-to the measurement of market activities and effects and marketing indicators. The data collected allow us to conclude that the surveyed organisations collect data that enables analysing different aspects and levels of the organisation’s market activity. Thus, it can be assumed that the Polish marketers surveyed perceive their activities in a rather holistic and comprehensive manner, taking into account the broader perspective of the organisation and its environment — which corresponds with the assumptions of EBM. At the same time, it is worth underlining that the range of data used is sufficient. On the one hand, owing to reasons such as difficulties arising from scarcity in data availability, economically unviable data acquisition costs, limitation in knowledge, etc., it may not be realistic to assume that 100% of companies will monitor even the most crucial indicators. On the other hand, it is possible to notice some room for broader use of certain metrics (e.g. sentiment analysis, CLV, GRP, purchase intention, customer retention costs and online sales costs). The research results presented do not make it fully possible to generalise them to the entirety of organisations operating on the Polish market. Nonetheless, they provide a rationale for reflection on the use of metrics, particularly in the context of their categorisation and frequency of use and their reference to an EBM approach.

To conclude, the observations mentioned above have likely brought out the need for the identification of future research directions that would facilitate exploration of additional metrics for deployment in identifying the efficacy of an organisation’s EBM processes.. One of them is deepening the analysis regarding the link between marketing objectives and the metrics used. Others include identifying the relationship between the metrics used and the performance of the organisation and the ability to make more effective decisions and building a relatively sustainable market advantage on this basis. It would also be of value in itself to assess the differentiation of results in relation to the specific characteristics of the company (size, operating model, etc.) or the market (B2B, B2C), etc.

Funding

The research presented in this article was conducted under the directions of the author and funded by the Accredited Study and Exam Center of The Chartered Institute of Marketing (questus).

References

1. Antman, E. M., Lau, J., Kupelnick, B., Mosteller, F., & Chalmers, T. C. (1992).

A comparison of results of meta-analyses of randomized control trials and recommendations of clinical experts. Journal of the American Medical Association, 268, 240–248.

2. Aram, J. D., & Salipante, J. P. F. (2000). Applied research in management: Criteria for management educators and for practitioner — scholars. In Paper presented at the US academy of management conference — Multiple perspectives on learning in management education, Toronto, Ontario.

3. Armstrong, J. S. (2001). Combining forecasts. In: J. S. Armstrong (red.), Principles of forecasting: A handbook for researchers and practitioners (pp. 417–440): Kluwer Academia Publishers, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

4. Barends, E., & Rousseau, D. M. (2018). Evidence-based management: How to use evidence to make better organizational decisions: Kogan Page, London, UK, New York, NY.

5. Brennan, R. (2008). Theory and practice across disciplines: Implications for the field of management. European Business Review, 20(6), 515–528. doi:10.1108/09555340810913520

6. Bryman, A., & Bell, E. (2012). Business research methods: Oxford University Press.

7. Chaffey, D., & Ellis-Chadwick, F. (2019). Digital marketing: Strategy, implementation and practice: Pearson, Upper Saddle River.

8. Chavez, T., O’Hara, C., & Vaidya, V. (2018). Data driven: Harnessing data and AI to reinvent customer engagement: McGraw Hill, New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Athens, London, Madrid, Mexico City, Milan, New Delhi, Singapore, Sydney, Toronto.

9. Cook, D. J., Mulrow, C. D., & Haynes, R. B. (1997). Systematic reviews: Synthesis of best evidence for clinical decisions. Annals of Internal Medicine, 126(5), 376–380.

10. Czarniawska, B. (2021). Badacz w terenie, pisarz przy biurku. Jak powstają nauki społeczne? Łódź. Wydawnictwo SIZ.

11. Davis, J. (2007). Measuring marketing: 103 key metrics every marketers need: John Wiley & Sons, Singapore.

12. Denyer, D., & Neely, A. (2004). Introduction to special issue: Innovation and productivity performance in the UK. International Journal of Management Reviews, 5/6(3&4), 131–135. doi:10.1111/j.1460-8545.2004.00100.x

13. Eckerson, W. W. (2005). Performance dashboards: Measuring, monitoring, and managing your business: John Wiley & Sons.

14. Farris, P. W., Bendle, N. T., Pfeifer, P. F., & Reibstein, D. J. (2010). Marketing metrics: The definitive guide to measuring marketing performance: Pearson Education.

15. Grove, W. M. (2005). Clinical versus statistical prediction. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 61(10), 1233–1243. doi:10.1002/jclp.20179

16. Hemann, C., & Burbary, K. (2013). Digital marketing analytics: Making sense of consumer data in a digital world: Que Publishing, Indianapolis, Indiana.

17. Hodgkinson, G. P., Herriot, P., & Anderson, N. (2001). Re-aligning the stakeholders in management research: Lessons from industrial, work and organizational psychology. British Journal of Psychology, 12(1), 41–48. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.12.s1.5

18. Kotarbiński, T. (1973). Traktat o dobrej robocie: Ossolineum, Wroclaw.

19. Kozielski, R. (2015). Wskaźniki marketingowe: Wydawnictwo Nieoczywiste, Warszawa.

20. Kozielski, R. (2022). Rynkowy due diligence. Pomiar odporności rynkowej organizacji: PWN, Warszawa.

21. LaPointe, P. (2005). Marketing by the dashboard light: Association of National Advertisers, New York, NY.

22. Lemon, K. N., & Verhoef, P. C. (2016). Understanding customer experience throughout the customer journey. Journal of Marketing, 80(6), 69–96. doi:10.1509/jm.15.0420

23. Lewis, M. (2004). Moneyball: The art of winning an unfair game: W. W. Norton & Company, New York, NY.

24. Longbottom, D., & Lawson, A. (2017). Alternative market research methods: Market sensing: Routledge, London, New York, NY.

25. McDonald, M., Smith, B. D., & Ward, K. (2007). Marketing due diligence: Reconnecting strategy to share price: Butterworth-Heinemann, Oxford.

26. McNees, S. K. (1990). The role of judgment in macroeconomic forecasting accuracy. International Journal of Forecasting, 6(3), 287–299. doi:10.1016/0169-2070(90)90056-H 27. Mulrow, C. D. (1987). The medical review article: State of the science. Annual International Medicine, 106, 485–488.

28. Pfeffer, J., & Sutton, R. I. (1999). Knowing 'what’ to do is not enough: Turning knowledge into action. California Management Review, 42(1), 83–108. doi:10.2307/41166020

29. Provost, F., & Fawcett, T. (2013). Data science for business: What you need to know about data mining and data-analytic thinking: O’Reilly Media, Beijing, Cambridge, Farnham, Koln, Sebastopol, Tokyo.

30. Radziszewski, P. (2016). Business intelligence: Moda, wybawienie czy problem dla firm? Wydawnictwo Poltext, Warszawa.

31. Rowley, J. (2012). Evidence-based marketing. A perspective on the 'practice-theory divide’. International Journal of Market Research, 54(4), 521–541. doi:10.2501/IJMR-544-521-541

32. Sharp, B., Wright, M., Kennedy, R., & Nguyen, C. (2017). Viva la revolution! For evidence-based marketing we strive. Australasian Marketing Journal, 25(4), 341–346. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2017.11.005

33. Shaw, R., & Merrick, D. (2005). Marketing payback: Is your marketing profitable: Financial Times Prentice Hall.

34. Silver, N. (2012). The signal and the noise: Why so many predictions fail — but some don’t: Penguin, New York, NY.

35. Sterne, J. (2002). Web metrics: Proven methods for measuring website success: Wiley Publishing.

36. Szpanderski, A. (2008). Podstawy prakseologicznej teorii zarządzania. MBA, no.3. Retrieved from https://publisherspanel.com/api/files/view/1314.pdf

37. Taylor, F. W. (1911). The principles of scientific management: Harper & Row, London, New York, NY.

38. Tetlock, P. E. (2006). Expert political judgment: Princeton University Press, Princeton, New Jersey.

39. Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., Marcos, J., & Burr, M. (2004). Co-producing management knowledge. Management Decision, 42(3/4), 375–386. Retrieved from https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1108/00251740410518895

40. Tranfield, D., Denyer, D., & Smart, P. (2003). Towards a methodology for developing evidence-informed management knowledge by means of systematic review. British Journal of Management, 14(3), 207–222. doi:10.1111/1467-8551.00375

41. Wind, J., & Nueno, P. (1998). The impact imperative: Closing the relevance gap of academic management research. In Paper presented at the International Academy of Management North America meeting, New York, NY.

42. Wind, Y., & Sharp, B. (2009). Advertising empirical generalizations: Implications for research and action. Journal of Advertising Research, 12(2), 246–252.

Jesslyn Yen — is a Bachelor Degree of Accounting from the Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics

and Business, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia. Antonius Herusetya is an Associate Professor in the

Department of Accounting, Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia.

Antonius Herusetya — is a Doctor in Accounting and an Associate Professor in the Department of Accounting,

Faculty of Economics and Business, Universitas Pelita Harapan, Indonesia.