- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Areas of influence in influencer marketing. To what extent is the communication under brand control?

Anna Łaszkiewicz

Department of Marketing, Faculty of Management, University of Łódź, ul. Matejki 22/26, 90-237 Łódź, Poland

E-mail: anna.laszkiewicz@uni.lodz.pl

Anna Łaszkiewicz; ORCID: 0000-0001-6202-6239

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0018

Abstract:

The article discusses the issue of influencer marketing in the context of social, technological and individual changes that affect the effectiveness of marketing communications. Limitations resulting from consumer preferences, media fragmentation and information overload make it increasingly difficult for brands to build awareness and reach audiences. Influencer marketing is an area that is increasingly willing to be used in the communication mix, but also in this area, we observe a growing number of limitations, which are worth being aware of when planning activities in this area. The purpose of this paper is to identify the limitations arising from the use of algorithms by social media platforms that determine the layout and visibility of content in the feed. The author developed an overview of algorithm changes on the Instagram platform and reviewed the literature on this issue concerning the Instagram platform, which is indicated as the most frequently used by marketers for activities in the field of influencer marketing. Visibility restrictions due to algorithms affect not only brands but also influencers. However, influencers take a number of actions to recognise the rules imposed by algorithms, thus building greater visibility for their content. Additionally, they can support brands with their expert experience. Therefore, the choice of an influencer for cooperation should, in addition to essential parameters related to brand fit, consider the effectiveness of reaching new audiences through the skilful use of knowledge and experience in the changing rules of algorithms.

MINIB, 2022, Vol. 46, Issue 4

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0018

P. 1-16

Published December 30, 2022

Areas of influence in influencer marketing. To what extent is the communication under brand control?

Introduction

The transition of the 20th into the 21st century is a period of many significant and often revolutionary changes related to or initiated by the spread of information technology. The main carrier of these changes was the emergence of the Internet and the possibility of direct, single- or multi-person communication and direct interaction. The digital economy is changing the realities of marketing communications, its forms, the palette of available tools and subsequent breakthroughs in the areas of elationship building, sales and advertising. These challenges are considered in numerous academic publications (Mazurek & Tkaczyk, 2016; Gregor & Kaczorowska-Spychalska, 2018; Bartosik-Purgat, 2019; Wiktor & Sanak-Kosmowska, 2021). With the emergence of social media, Internet participants gained the opportunity for creative expression, exchange of experiences, and creation of original content, with almost no restrictions.It follows that users familiar with the usage of Internet-based technologies were the main source from which the newly emergent Internet-based business models at the time derived their principal utility and value, and in particular the emergence of the advent of social-media-based marketing gave rise to a new generation of businesses that typically channelised a significant portion of their revenue from avid social-media users. Internet users, especially on social media, became both receivers and creators of the offered value. Their influence on consumer decisions remains unquestionable today-from simple decisions related to choosing a restaurant, a book to read or a museum worth visiting in a given location, or booking a specific destination for a business trip or family vacation; to decisions that change economic, social and political reality, such as shaping beliefs and decisions in parliamentary or presidential elections. Creators using the Internet have thus become another source of information, competing for consumers’ attention with professional information services, trade media and the so-called ‘reliable sources of information’. This is due to the premises mentioned above, namely dissemination and development of digital technologies, including mobile technologies. In addition, the opportunity to contact and learn about the opinions and experiences of people similar to oneself, i.e. ordinary people constituting users of the Internet and social media, possibly from one’s own or a related interest group, has gained importance (Kaczorowska-Spychalska, 2020).

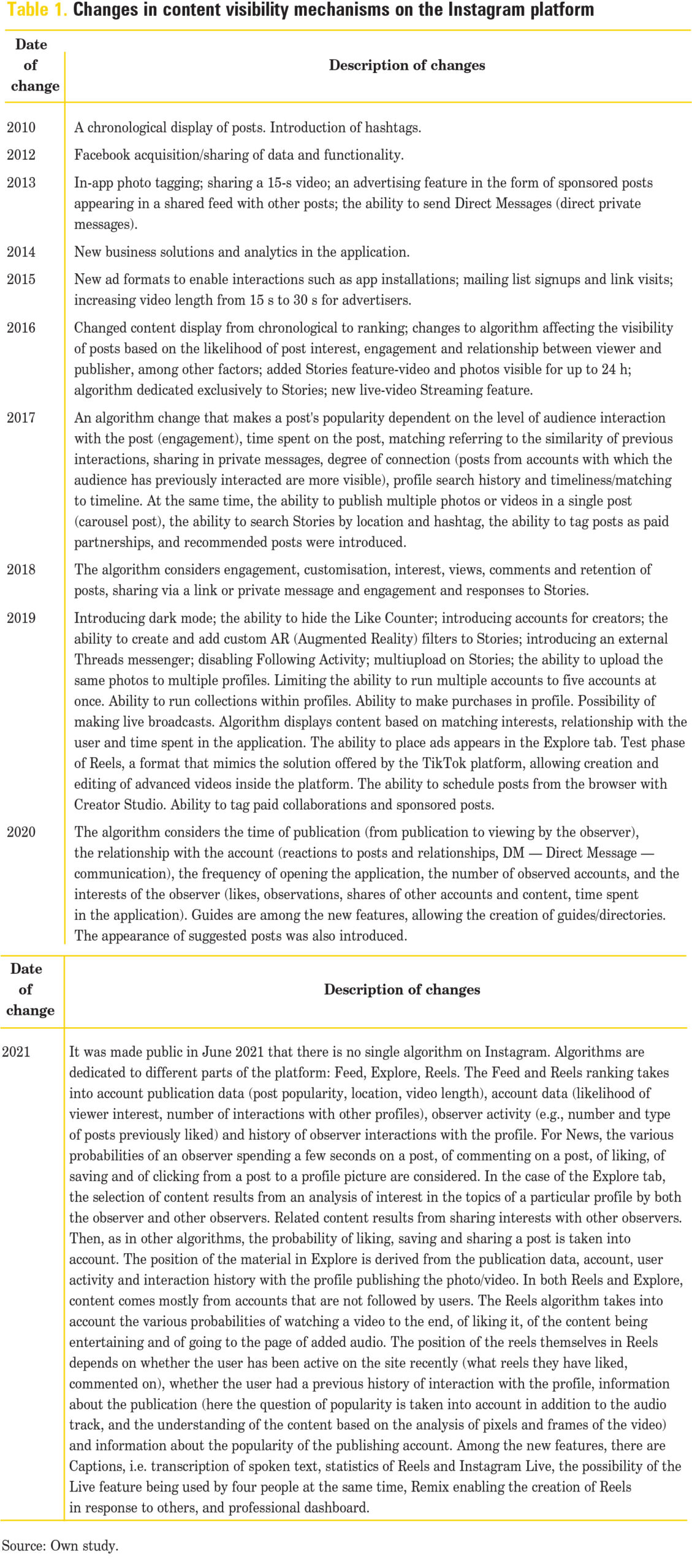

Regulatory Forces in a Creative Environment

User-generated content (UGC) is typically created voluntarily. In other words, it is not paid for by its creators. Creative expression can take many forms, given the available and growing opportunities to share knowledge, news, creativity and activities of all kinds. Digital creators express themselves mainly through photos/images on platforms such as Instagram, Pinterest and Snapchat; and through video formats using TikTok, YouTube and Vine. They publish their advice, opinions, comments and analyses not only in virtual spaces dedicated to longer forms, such as blogs, but also in the form of shorter statements and updates on commonly visited social networking sites, such as Twitter, Facebook, LinkedIn or Quora. The mentioned activities do not exhaust all possible forms of expression. In the area of content creation, it is also worth mentioning the publication of reviews, e.g. on Amazon or TripAdvisor, comments and content within sharing platforms such as Uber or Airbnb, crowdfunding activities, e.g. on the Kickstarter platform, or contributing to the content forming part of Wikipedia. The quality of posted content is increasingly subject to scrutiny, although it is essential to keep in mind that both the subject matter and the medium’s specifics will influence the message’s final reception. However, as previous studies have shown, reviews posted online by independent community members are usually consistent with expert opinions (Luca, 2015). It is worth noting that the Internet environment, especially the space allowing for the creation of independent content by individual creators, is increasingly subject to the activities of companies, politicians and other centres wishing to exert influence through the mass formulation of opinions. This involves not only activities that stimulate interest in a given issue, company or politician, such as generating posts or comments on request, and paying for promotional activities using, for example, influencers or influential experts, but also unethical activities of these entities such as fake reviews. Their scale may be difficult to estimate. A study by Luca and Zerwas (2016) analysed over 316,000 reviews of restaurants operating in the Boston area using an algorithm developed by Yelp. They identified 16% of the reviews flagged as suspicious by the algorithm. This takes on particular significance because previously published content influences subsequent publications and their tone. A study by Muchnik, Aral, and Taylo (2013), which analysed content published on a platform with the ability to rate articles by voting, showed that information with positive votes increased the likelihood of attracting subsequent positive votes by 32% (Luca, 2015). On the other hand, we have all kinds of ‘distortions’ in the visibility of published content resulting from the content sharing algorithm imposed by social media platforms. The algorithm and the criteria that are taken into account play a key role in selecting the content displayed and ultimately determining what content among all the content published will be seen by the users of the platforms (Skorus, 2020). According to Instagram’s Head of Product, only half of the content published by profiles, including brand profiles, is visible to those who follow those profiles (https://influmarketing.pl/ algorytm-instagrama-2021-duzo-nowej-wiedzy-od-samego-instagrama/, 2022). Additionally, often the exact workings of the algorithm are not made public, other than what areas of publishing activity are considered in the construction of the algorithm. In June 2021, the Head of Instagram, Adam Mosseri, published an article that closely examines how content display mechanisms work on Instagram. The article begins with the sentence, ‘It’s hard to trust what you don’t understand.’ (Mosseri, 2021). Changes in the display of content on the Instagram platform are presented in Table 1. Raychoudhury (2022), Meta’s Vice President and Head of Research, argues-in his article published on Meta’s corporate portal-against the growing voices that have pointed out that social media algorithms exercise a significant, and even predominant, influence on the already-ascendant polarisation of society and the formation of information bubbles. The article emphasises that the contribution of social media to the phenomena described is much more complex, and the mainstream media play a more significant role in disinformation. A 2019 study conducted by Nielsen on a sample of more than 25,000 respondents found that only 9% of consumers are confident of the impartiality of the algorithms behind the so-called social media feed (Cigionline.org, 2020).

Is Influencer Marketing a Solution?

Since doubts prevail widely concerning the veracity of the information made available through social media platforms in particular and the Internet in general, several areas of the economy and multiple facets of its operation, especially businesses whose primary marketing modus operandi involves using an online mode of information propagation, are faced with the crises of loss of trust, and credibility being called into question; such a situation poses a significant challenge that could be potentially overcome by running an online campaign explaining ‘things from the enterprise’s point of view’. (Pasek, 2018). In their case, effective communication is one of the critical factors in building brand awareness on the market, and reliable information is also a tool to build a true identity of the company. Companies exposed, on the one hand, to the activities of unfair competition and demanding customers and, on the other hand, to difficult-to-predict changes in algorithms affecting the visibility of published content began to see the benefits of working with influencers. These are individuals who, as a result of their activity on the Internet, have gained the trust of their observers, thus becoming influential persons, especially about purchasing decisions and attitudes of buyers towards brands, or more broadly defined, ideas. These are known as influencers because they are people who formulate specific opinions and influence their recipients with the content they create, typically through selected channels on social media. The idea of brand ambassadors is nothing new. The first-known ambassador was Queen Charlotte, who represented the Queen’s Ware line of Wedgwood brand back in the 18th century. Recommendations from well-known and respected personalities have effectively influenced consumer choices for centuries. The turn of the 20th century, ushering in the development of technology, introduced the possibility of mass communication; and the advantages of television, radio and newspaper advertising addressed at a large audience became a much more practical solution for entrepreneurs, with regard especially to the wide-range of communication possibilities offered by these new media. It was not until the advent of the Internet and a turn away from traditional media, especially among the younger generation, that companies again began to see the potential of non-standard solutions, including the potential of influencers who combined all the features of former brand ambassadors with the high reach of mass media. It is worth noting that 2021 in Poland was characterised by the advantage of online advertising over TV advertising, amounting to 42.7% and 42.4%, respectively. The remaining 14.9% of the advertising market consisted of radio advertising (7.4%), outdoor advertising (3.8%), magazines and dailies (total 3.1%) and cinema advertising (0.6%) (https://interaktywnie.com/biznes/newsy/biznes/rynek-reklamowy-wpolscewiekszy-niz-przed-pandemia-na-czele-reklama-online-261981, 2022). If we additionally consider the activity of Internet users in blocking online ads and the phenomenon of the so-called banner blindness (https://www.emarketing.pl/reklama-internetowa/slepota-banerowa-dlaczego-internauci-ignoruja-reklamy/, 2022), then influencer marketing seems to be an attractive solution for the institution of an effective mechanism for brand propagation.

The estimated value of the influencer marketing market in 2022 will reach $15 billion. Considering the 2019 market value of $9 billion, there is a great interest in this kind of activity in the world (https://raportstrategiczny.iab.org.pl/raport/influencer-marketing/, 2022). Also, in Poland, cooperation with influencers is becoming increasingly popular. The LTTM network paid out US$ 42 million to influencers, and the estimates of the value of the influencer market in Poland on the Instagram platform increased from US$ 18.7 million in 2019 to US$ 22.7 million in 2020 (https://raportstrategiczny.iab.org.pl/raport/influencer-marketing/, 2022). Unfortunately, the influencer marketing market in Poland is not researched in terms of advertising expenses dedicated to cooperation with influencers, and thus it is difficult to say what percentage of the advertising pie these activities represent. It is especially worth emphasising that brandrelated activities and recommendations of influencers enjoy a maximum of 71% trust so far as consumers are concerned, whereas trust above 80% is only achieved by recommendations of friends (89%) and by the brand’s website (84%). On the other hand, advertising activities on the Internet do not enjoy a high level of trust among Internet users. Banner ads are distrusted by 38% of them, social media and search engine ads are distrusted by 36% of respondents, 34% of Internet users consider ads on mobile devices to be untrustworthy and 33% of Internet users consider online videos to be untrustworthy (https://annualmarketingreport.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/pdf/full_report_1649855483_4140011690.pdf, 2022). In addition to the issues of trust and changes in media consumption, including traditional media, mainly among the young audience, who typically tend to belong to generation Z, significant is the phenomenon of the emergence of solid ties between the influencer and his audience. According to the Nielsen report, especially in the last 2 years, a period associated with the pandemic and very often the need to physically restrict social contact, the relationship between influencers and their followers has grown significantly, and influencers themselves began to be seen as one of the most reliable sources of information about brands and sales channels. Indeed, the source of this success, particularly the bonds built, is the perception of influencers as ‘people from the neighbourhood’. Influencers who do not belong to the category of ‘celebrity influencers’ are usually ordinary Internet users who share their passions and daily choices and regularly report on events in their lives. What is particularly attractive is that the influencer market is very diverse, making it possible to choose a specific influencer in terms of the desired topic and the reach or number of followers. Any brand can work with an influencer, even brands with small advertising budgets. The popularity arising from the results achieved is not only mega influencers with several million followers or celebrity influencers with similar reach but also micro or nano influencers who are followed by a smaller audience. According to Omnicore data, for every $1 invested in influencer marketing activities on Instagram, marketers reach $5.20 (https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/, 2022). It makes this marketing activity worth considering and including in the brand’s promotional mix. Of course, influencers can only influence their audience if they can both gain and maintain their attention (Hearn & Schoenhoff, 2015).

Methodology

In order to identify the impact of algorithms on the freedom and effectiveness of social media communication, it was decided to conduct a narrative literature review. In addition to the methodology of a systematic literature review, a narrative review of the literature is applied, especially in cases where there are few scientific papers on the topic under study (Rozkwitalska, 2016). Establishing the state of knowledge in the research subject up to the present time is important for conducting empirical studies and creating new knowledge (Czakon, 2015). It should be mentioned that by effectiveness, the author means the message’s visibility to the social media user and not its persuasive function. For this purpose, the Web of Science database was searched using the words and phrases ‘algorithm’ or ‘algorithms’ or ‘filter bubble’ or ‘algorithmic power’ and ‘Instagram’ and ‘marketing’ and ‘social media’ and ‘influencer’, considering all search fields. The decision to choose the words ‘marketing’ and ‘Instagram’ was dictated by the specificity of the analysed issue, which should refer to marketing activities using the most popular influencer marketing platform. Research shows that most marketers (89%) and consumers (65%) indicate the Instagram platform as the most popular choice for influencer marketing activities and influencer followings (https://www.fourstarzz.com/post/instagram-influencer-marketing, 2022). Instagram is also indicated as the platform of choice by 78% of marketers worldwide for influencer marketing activities (https://www.tractionwise.com/ wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Industry-Report-2021-Final.pdf, 2022). The author then narrowed the results to articles in peer-reviewed journals in behavioural sciences, communication, business and economics and narrowed the date range from 2016, when Instagram abandoned the chronological display of content, to the present. The results were then narrowed to publications in English, yielding 12 articles. As a result of the content analysis, eight articles were rejected due to the lack of references to the Instagram platform and lack of relevance to the issue under study.

Discussion

The final analysis was conducted on four articles. In them, the authors draw attention to the invisible influence of algorithms on social media activities (Cotter, 2019) and the peculiar game that content creators seem to be playing, in which identifying the ‘rules’ of algorithms is fundamental. Cotter (2019) calls this the ‘visibility game’ while pointing out the significant role of influencers in working out visibility rules, which can guide brands and help identify behaviours that improve publication visibility. Algorithms significantly impact the visibility of communications and mainly influence the structure of experiences and social realities on social media, although not necessarily user behaviour (Cotter, 2019). Influencers, as people who care about visibility and reaching their followers, place great importance on collecting information about how algorithms work: they read expert blogs, participate in discussions and collect examples of actions. Research by Cotter (2019) shows that influencers are mainly interested in two areas of information: information that reveals what influences the visibility of communication (such as the choice of hashtags, ideas for building engagement or the times and frequency of publication) and what are the acceptable boundary behaviours (such as what is perceived as spam, or what tools are acceptable to use by the Instagram platform). It includes the phenomenon of shadowbanning, which involves limiting the visibility of posts due to violating the platform’s rules, virtually blocking the reaching of new audiences and expanding the reach of posts (Cotter, 2021). Certainly, influencers, for whom visibility is one of their primary activities, based on their experiences, see in advance and recognise signals of censorship, discrimination or unequal application of policies (Cotter, 2021). Gaenssle and Budzinski (2019) refer to the algorithm as part of effectively serving advertising messages to the most tailored audience. The authors show the algorithm discussed so far in a different context as a supportive tool for optimising corporate advertising spending. They emphasise the importance of experience in dealing with algorithms that determine the visibility of content for web developers. They also point out that experience resulting from time spent on the platform and constant experimentation to improve content visibility become factors that build an influencer’s expert position and create a barrier to entry for new creators. Gaenssle and Budzinski (2019) refer, like Cotter, to the notion of a ‘game’ while emphasising that winning (in this case with an algorithm or a recommender system) can create a snowball effect and improve the visibility of a given influencer. O’Meara (2019), on the other hand, refers to the problem of algorithms influencing the working conditions of digital creators by identifying ‘worker resistance’ activities. As an example, he gives bottom-up constituted groups, providing each other support by giving likes, shares, mentions and comments, which are measures of engagement. Engagement is a crucial element of the algorithm on the Instagram platform. Unlike Cotter, who presents a ‘game’ approach to visibility that assumes a rather individual and even expert dimension, the author sees visibility efforts on the platform as a collective effort by a specific community. One of the effects achieved by influencers by engaging in ‘engagement pods’ is also the professional building of an audience base that attracts brands interested in cooperation and improves the influencer’s negotiating position when establishing the terms of advertising cooperation with an interested company. However, these activities also face criticism from influencers who see them as fraud (O’Meara, 2019).

Conclusion

There are still many open questions and issues in the field of influencer marketing that need to be explored or verified. The social impact of the content generated by Internet users, especially by influencers, is gaining importance. Influencers are becoming a kind of ‘creative enterprise’ by transforming their activity and presence on social media platforms into a product consumed by the acquired audience and as an advertising medium for advertisers (O’Meara, 2019). To what extent can activities using social influence enter the canon of marketing tools and contribute to generating recognisable and comparable effects? Indeed, by observing the activities of social platforms, we can see efforts being made to impose specific rules for publishing and serving content that is shared not only by brands but also by digital creators. The shift from chronological publishing of materials shared by profiles to mechanisms serving photos and videos according to a planned scheme is supposed to, on the one hand, improve the visibility of valuable content, but, on the other hand, it introduces many conditions to be met. Additionally, the visibility of observed profiles was reduced by serving in the news not only content published by observed profiles but also ads and sponsored content. Considering the time users spend browsing Instagram, published posts compete for attention with advertising and sponsored posts. A review of the changes that took place in the algorithm and content ranking mechanisms on Instagram, especially the changes introduced after 2020, further indicates the great importance of creating thoughtful and consistent content. In this dimension, better results can be observed by influencers with a clearly defined profile of activity. Influencers whose activity is diverse may face difficulties in reaching a broad audience. The issue under discussion and the method used have some limitations. Changes related to algorithms are being made all the time, and information about them is not widely available. The literature analysis conducted also has its limitations. A review of other databases could identify additional scientific publications for analysis. The number of articles referring to the issue in question remains small and raises the need for further research that could provide answers to additional questions. To what extent does the visibility of content moderated by algorithms affect aspects of consumer perception and behaviour and brand image? How can knowledge of algorithms among influencers determine their negotiating position with brands?

What are the implications of the above considerations for brand owners? Online marketing is one of the technology trends impacting marketing and online sales (Trzmielak & Zehner, 2018). Advertised and suggested posts appearing in the news can be successfully used to improve the visibility of the brand profile or promoted content. On the other hand, openly reaching out to the community of influencers and presenting the brand as a perpetually improving continuum that has arisen and is being maintained as an outcome of cooperation between its creators and the providers of feedback on the various digital platforms is a chance to build engaging content and context in which to display the brand among an interested audience. However, bearing in mind the limitations described above, when deciding to work with an influencer, it is worthwhile to pay attention to the profile of their activity, especially its consistency and uniformity, in addition to several essential criteria such as reach, audience profile, engagement of followers and authenticity of the influencer. It would help if managers also considered to what extent the cooperation with an influencer will be an essential element of the brand’s promotional mix.

References

1. Bartosik-Purgat, M. (2019). New media in the marketing communication. On enterprises in the international market. Warszawa, Poland: PWN.

2. Cigionline. (2020). CIGI-Ipsos Global Survey on Internet Security and Trust. [online].

Retrieved from https://www.cigionline.org/sites/default/files/documents/2019%20CIGIIpsos% 20Global%20Survey%20%20Part%203%20Social%20Media%2C%20Fake%20News%20%26%20Algorithms.pdf (accessed 26 May, 2022).

3. Cotter, K. (2019). Playing the visibility game: How digital influencers and algorithms negotiate influence on Instagram. New Media and Society, 21(4), 895–913. doi:10.1177/1461444818815684

4. Cotter, K. (2021). Shadowbanning is not a thing: Black box gaslighting and the power to independently know and credibly critique algorithms. Information, Communication and Society. 1–20, doi:10.1080/1369118X.2021.1994624

5. Czakon, W. (Ed.). (2015). Podstawy metodologii badań w naukach o zarządzaniu. Wydanie III rozszerzone. Warszawa, Poland: Oficyna Wolters Kluwer Business.

6. Gaenssle, S., & Budzinski, O. (2019). Stars in social media: New light through old windows? Ilmenau Economics Discussion Papers, 25(123), 1–50. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3370966 7. Gregor, B., & Kaczorowska-Spychalska, D. (Ed.). (2018). Marketing w erze technologii cyfrowych. Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

8. Hearn, A., & Schoenhoff, S. (2015). From celebrity to influencer. In P. D. Marshall & S. Redmond (Eds.), A companion to celebrity (pp. 194–212). Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

9. Interaktywnie.com. (2022). Advertising Market in Poland Larger than before the Pandemic. Online Advertising in the Lead [online]. Retrieved from https://interaktywnie.com/biznes/newsy/biznes/rynek-reklamowy-w-polsce-wiekszy-nizprzedpandemia-na-czele-reklama-online-261981 (accessed 15 April, 2022)

10. Internet 2020/2021. Strategic Report. IAB Poland.

11. Kaczorowska-Spychalska, D. (2020). Influencer marketing. In R. Kozielski (Ed.), The future of marketing. Concepts, methods, technologies. Theory and application (pp. 334–344). Łódź, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

12. Luca, M. (2015). User-generated content and social media. Handbook of media economics: Elsevier B.V. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-63685-0.00012-7

13. Luca, M., & Zervas, G. (2016). Fake it till you make it: Reputation, competition, and yelp review fraud. Management Science, 62(12), 3412–3427.

14. Mazurek, G., & Tkaczyk, J. (Ed.). (2016). The impact of the digital world on management and marketing. Warszawa, Poland: Poltext.

15. Mosseri, A. (2021). Shedding More Light on How Instagram Works. Retrieved from https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/shedding-more-light-on-how-instagram-works (Accessed 16 May, 2022)

16. Muchnik, L., Aral, S., & Taylor, S. J. (2013). Social influence bias: A randomized experiment. Science, 341(6146), 647–651. doi:10.1126/science.1240466

17. O’Meara, V. (2019). Weapons of the chic: Instagram influencer engagement pods as practices of resistance to Instagram platform labor. Social Media Society, 5(4), 1–11. doi:10.1177/2056305119879671

18. Pasek, A. (2018). Konflikt między zaufaniem a nieufnością do informacji Iiternetowej. I pochodzącej z mediów tradycyjnych. Rzeszowskie Studia Socjologiczne, 11(2018), 124.

19. Raychoudhury, P. (2022). What the Research on Social Media’s Impact on Democracy and Daily Life says (and Doesn’t Say) [online]. Retrieved from https://about.fb.com/news/2022/04/what-the-research-on-social-medias-impact-ondemocracyand-daily-life-says-and-doesnt-say/ (accessed 6 May, 2022)

20. Rozkwitalska, M. (2016). Efekt kraju pochodzenia a ocena kompetencji zawodowych obcokrajowca — przegląd narracyjny. Przedsiębiorczość i Zarządzanie, XVII, 2(3), 125–136.

21. Skorus, J. (2020). Komunikacja we władzy algorytmów: szansa czy zagrożenie? Zeszyty Naukowe Wyższej Szkoły Zarządzania Ochroną Pracy w Katowicach, 1(16), 77.

22. Trzmielak, D. M., & Zehner, W. B. (2018). Marketing of new technologies and products — Perspectives, challenges, and actions. Handel Wewnetrzny, 5, 289–299.

23. Wiktor, J. W., & Sanak-Kosmowska, K. (2021). Information asymmetry in online advertising (1st Ed.), London and New York: Routledge, Taylor&Francis Group. doi:10.4324/9781003134121

Netography

1. Retrieved from https://about.instagram.com/blog/announcements/shedding-more-lightonhow-instagram-works (accessed 20 May, 2022).

2. Retrieved from https://annualmarketingreport.nielsen.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/16/pdf/full_ report_1649855483_4140011690.pdf (accessed 12 May, 2022).

3. Retrieved from https://influmarketing.pl/algorytm-instagrama-2021-duzo-nowej-wiedzyod-samego-instagrama/ (accessed 16 May, 2022).

4. Retrieved from https://influmarketing.pl/zmiany-na-instagramie-2019-2020/ (accessed 20 May, 2022).

5. Retrieved from https://powerdigitalmarketing.com/blog/instagram-algorithm-changehistory/# gref (accessed 20 May, 2022).

6. Retrieved from https://influmarketing.pl/zmiany-na-instagramie-2019-2020/ (accessed 12 May, 2022).

7. Retrieved from https://raportstrategiczny.iab.org.pl/raport/influencer-marketing/ (accessed 12 May, 2022).

8. Retrieved from https://www.emarketing.pl/reklama-internetowa/slepota-banerowadlaczegointernauci-ignoruja-reklamy/ (accessed 26 May, 2022).

9. Retrieved from https://www.fourstarzz.com/post/instagram-influencer-marketing (accessed 20 May, 2020).

10. Retrieved from https://www.omnicoreagency.com/instagram-statistics/ (accessed 12 May, 2022).

11. Retrieved from https://www.tractionwise.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Industry-Report-2021 -Final.pdf (accessed 20 May, 2022).

12. Retrieved from https://www.emarketing.pl/reklama-internetowa/slepota-banerowadlaczegointernauci-ignoruja-reklamy/ (accessed 20 May, 2022).

Anna Łaszkiewicz — Management and quality sciences doctor. Faculty of Management at the University of Lodz lecturer since 2003. Director of postgraduate studies in eCommerce. Her research interests include the issue of business and consumer value in the context of the use of technology, especially the Internet, in digital marketing, social media, and influencer marketing. She is the author and co-author of English- and Polish-language publications devoted to such issues as e-business, e-commerce, social media, digital and influencer marketing, and buyer behavior. At the same time, she is active in the sphere of business practice.