- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

The greening of consumption: challenges for consumers and businesses

Anna Dąbrowska1, Paweł Jurowczyk2, Irena Ozimek3

1Consumer Behaviour Research Department, Warsaw School of Economics, Institute Management, Poland

2ABR SESTA Market Research and Consulting, Poland

3Department of Development Policy and Marketing, Institute of Economics and Finance,

Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Warsaw, Poland

Anna Dąbrowska; adabro3@sgh.waw.pl

Anna Dąbrowska; ORCID: 0000-0003-1406-5510

Paweł Jurowczyk; ORCID: 0000-0001-6412-8431

Irena Ozimek; ORCID: 0000-0003-3430-8276

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0015

Abstract:

The concern for the condition of the natural environment requires taking a new approach towards consumption and meeting consumer needs (Bocking 2009). Despite many initiatives related to the paradigm of sustainable development and the concept of sustainable consumption, the situation is still far from a general departure from mass consumption and consumerism. The article aims to try to synthetically organise the views of other authors on the challenges of greening consumption, both for enterprises and consumers in the context of social responsibility. Competences play an important role in this process. The greening of consumption has not yet been widely propagated in societies, including also Polish society. One of the crucial elements of greening consumption is the purchase of ecological/organic food products. To learn about the behaviour of Poles towards the issue discussed in this article, the authors conducted a study on a representative sample of Poles (N = 1,000) during Nov. 15–27, 2021, using the Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) technique (which is an online surveying technique that fits into the quantitative methodology of market and opinion research) and online panels as part of the omnibus study. The survey shows that only 7.1% of the respondents have never purchased ecological/organic food products. Among buyers, 21.8% do it rarely/sporadically, 40.1% occasionally/sometimes, 20.2% often/try to choose ecological products when shopping and 10.8% do it very often or always. Among the respondents, 55.3% declared that ecological/organic products are expensive but still worth the price due to the health benefits they bring. Noticing the advantages of these products, 63.7% of respondents would like to buy more of them. In view of the results obtained, it can be said that it is necessary to disseminate the main greening consumption ideas that are apparent from this study, and this can be done through education, building consumer competences or visualising the effects of the continuation of current consumption habits. The problem of protecting the natural environment, discussed in numerous documents issued by governments and international organisations and in scientific publications, cannot remain unnoticed. Greening consumption is a challenge for companies whose production should be rational in using non-renewable natural resources, reducing or eliminating toxic waste, using recyclable packaging and introducing ‘clean production’ principles aimed at obtaining consumer products using more cost-effective and healthier methods. It is also a challenge for consumers, who should replace perishable goods with products with a longer life cycle, consume goods and services more sparingly and cease to accept planned obsolescence of products or unethical behaviour of enterprises towards their employees.

MINIB, 2022, Vol. 45, Issue 3

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0015

P. 44-56

Published 30 September 2022

The greening of consumption: challenges for consumers and businesses

Introduction

The greening of socio-economic life is one of the main challenges of the 21st century, whose aim is to counteract environmental degradation, progressive climate change and depletion of natural resources. The concern for the condition of the natural environment requires taking a new approach towards consumption and meeting consumer needs. Despite many initiatives related to the paradigm of sustainable development and the concept of sustainable consumption, the situation is still far from a general departure from mass consumption and consumerism. The EU authorities believe that the main reason for the negative impact of consumption on the environment and excessive use of resources is that the social costs of environmental and resource degradation are not fully reflected in the prices of goods and services (The European Environment, 2010). Generally, the greening of consumption is the desire of consumers to rationalise purchasing and consumption behaviour in order to reduce the negative effects of excessive exploitation of natural resources as well as post-consumption waste, which also has an impact on the condition of the environment. Changes in the perception of consumption may be observed among informed consumers. Namely, the prestige associated with buying and owning goods is losing its importance in favour of reducing consumption or choosing ecological products. It is possible to notice a change in consumer behaviour-i.e. moving from ‘homo oeconomicus’ to ‘homo ecologicus’. Such behaviour requires competence, activity and response to negative actions of enterprises. Companies operating internationally, nationally and locally should take into account changes in consumer attitudes and their value systems in their production, sales and marketing activities. The article aims to try to synthetically organise the views of other authors on the challenges of greening consumption, both for enterprises and consumers in the context of social responsibility. Competences play an important role in this process. The greening of consumption has not yet been widely propagated in societies, including also Polish society. One of the crucial elements of greening consumption is the purchase of ecological/organic food products. To learn about the behaviour of Poles towards the issue discussed in this article, the authors conducted a study on a representative sample of Poles (N = 1,000) during Nov. 15–27, 2021, using the Computer Assisted Web Interview (CAWI) technique (which is an online surveying technique that fits into the quantitative methodology of market and opinion research) and online panels as part of the omnibus study. Implementation of the adopted goal, as well as learning about the behaviour of Poles towards the greening of consumption, required the formulation of the following research questions:

- When buying food to meet household needs, do Poles buy organic products and with what frequency?

- How do consumers perceive organic/organic products?

- Does the behaviour of consumers differentiate socio-demographic characteristics?

The survey shows that only 7.1% of the respondents have never purchased ecological/organic food products. Among buyers, 21.8% do it rarely/sporadically, 40.1% occasionally/sometimes, 20.2% often/try to choose ecological products when shopping and 10.8% do it very often or always. Among the respondents, 55.3% declared that ecological/organic products are expensive but still worth the price due to the health benefits they bring. Noticing the advantages of these products, 63.7% of respondents would like to buy more of them. In view of the results obtained, it can be said that it is necessary to disseminate the main greening consumption ideas that are apparent from this study, and this can be done through education, building consumer competences or visualising the effects of the continuation of current consumption habits. The problem of protecting the natural environment, discussed in numerous documents issued by governments and international organisations and in scientific publications, cannot remain unnoticed. Greening consumption is a challenge for companies whose production should be rational in using non-renewable natural resources, reducing or eliminating toxic waste, using recyclable packaging and introducing ‘clean production’ principles aimed at obtaining consumer products using more cost-effective and healthier methods. It is also a challenge for consumers, who should replace perishable goods with products with a longer life cycle, consume goods and services more sparingly and cease to accept planned obsolescence of products or unethical behaviour of enterprises towards their employees (Rock, 2010).

The article contributes to the discussion and body of work on consumption and consumer behaviour, with a focus on greening.

The article is addressed to readers who are concerned with the problem of environmental degradation and social responsibility of businesses, and to consumers interested in adopting the trend of greening consumption and in choosing products for consumption that are both healthy and cause no or minimal damage to the environment; the present research would also be useful to academia, consumers and businesses, the latter among whom can use it to determine what kind of products are preferred by consumers who are focussed on greening consumption, and alter their capital composition, manufacturing and distribution mix accordingly

Greening of Consumption-Theoretical Background

The genesis of greening consumption dates back to the late 1960s. At that time, people were able to notice serious threats to the environment, and thus also to the functioning of economies and societies and to the quality of life. On May 26, 1969, the UN Secretary-General U Thant presented the famous report ‘The problems of the human environment’ to the international public. The report highlighted the worrying data indicating the destruction of the natural environment and its consequences, including lack of connection between the highly developed technology and environmental demands, destruction of arable lands, uncontrolled development of urban zones, reduction of free areas and open areas, the disappearance of many forms of animal and plant life, poisoning and pollution of the environment, and the need to protect such elements of the environment as soil, water and air. The report called on all countries to make wise decisions concerning the use of the Earth’s resources and to invest in ecosystem protection (United Nations, 1969).

The issue of saving the natural environment was also discussed by Meadows et al. (1972) in their publication entitled ‘Limits to Growth’ published by the Club of Rome in 1972. The authors analysed the future of humanity in the face of the increase of the number of inhabitants of the Earth and depleting natural resources and formulated the following conclusions:

1. If the present growth trends in world population, industrialisation, pollution, food production and resource depletion continue unchanged, the limits to growth on this planet will be reached sometime within the next 100 years. The most probable result will be a rather sudden and uncontrollable decline in both population and industrial capacity.

2. It is possible to alter these growth trends and to establish a condition of ecological and economic stability that is sustainable far into the future. The state of global equilibrium could be designed so that the basic material needs of each person on the Earth are satisfied and each person has an equal opportunity to realise his individual human potential (Meadows et al., 1972).

The issue of greening is an element of sustainable development (Trocki & Wachowiak, 2019), which, according to Daly (2007), is reduced to three principles: the rate of consumption of renewable resources should not be faster than the rate at which they regenerate; the rate of consumption of non-renewable resources should not be faster than the rate at which their renewable substitutes can be introduced; the rate of the pollutants and waste emissions should not be faster than the rate at which the natural systems can absorb, recycle or dispose of them.

Half a century has passed since pioneers started to write about the threats to the environment. Thus, a legitimate question arises as to whether the societies and consumers have changed their behaviour and their lifestyle, and whether the entrepreneurs take more responsibility for the offered products and marketing activities, and for the natural environment and the consumers’ quality of life. Has the so-called ‘crawling apocalypse’, which Jonas, the author of the book The Imperative of Responsibility — In Search of an Ethics for the Technological Age (Greisch, 1992) has commented on in his interview, receded? Are Jonas’s words: ‘the concern is this everyday use that we make of our power, which after all is the basis of our entire civilised existence with all conveniences and facilities (driving your own car, airplane flight, etc.), with all the incredible abundance of goods at our disposal’ still valid? As Jonas claims, ‘These are the things which do not deserve moral criticism: however, what we do is impossible to escape every day. It runs its own course. This means that the crawling apocalypse becomes more dangerous that the sudden and brutal apocalypse.’-has this crawling apocalypse come and passed, or is it yet to leave its most deleterious mark?

Two decades of the 21st century have passed, and the discussion on environmental protection and ecological consumption not only does not subside but actually intensifies. In this context, both consumers and businesses play their significant parts.

The pursuit of greening consumption to an ever-greater extent requires the cooperation of market participants, both consumers and entrepreneurs. Consumers must make the right choices when selecting the products available in the market, choosing those goods that are not harmful to the environment, and entrepreneurs play an important role in the process of shaping the shopping carts where there will be more and more ecological/organic products. These activities should be supported with the dissemination of relevant information about such products, which in turn affects the level of ecological awareness of consumers.

According to Mintel’s (2018, p. 4) forecasts, consumer awareness of the occurrence of plastics in the oceans, and their impact on the environment or human health, will increase in the near future. The effects of one-time use and subsequent disposal of plastic packaging are alarming. It is estimated that at least 150 million tons of plastic are in the seas, and 4.8–12.7 million tons of plastic is thrown into the ocean annually. According to one assessment, as far as weight is concerned, until 2050, there will be more plastic in the ocean than fish (European Parliament, 2018). That is why the Directive (EU) 2019/904 of the European Parliament and of the Council of June 5, 2019 on reducing the environmental impact of certain plastic products (Official Journal of the European Union, L 155/1, June 12, 2019) is so important. The basis of the changes is the pursuit of the circular economy, which aims to rationally use resources, e.g. through recycling and the use of reusable packaging. This directive must be introduced into the national regulations of particular EU countries by July 3, 2021; however, disposable plastic products covered by its individual provisions are listed in the annexe to the directive.

The greening of consumption may be reflected, among other things, in the growing ability to consume fashionable and high-quality products, using recycled items such as plastic clothing harvested from the ocean or the use of recycled packaging, as well as the use of reusable shopping bags. In the UK, 49% of British citizens would be interested in purchasing clothing or accessories made entirely or partly from recycled plastics, 72% would be interested in purchasing products with packaging made entirely/partly from recycled plastics, 73% are interested in a greater choice of beverages/food guaranteed to come from uncontaminated waters and 79% believe people should be encouraged to recycle plastics. In Poland, 66% of consumers say they prefer to drink water using recycled plastic bottles (Mintel, 2018, p. 6).

Pointing to consumer trends until 2030, based on the conducted research, Mintel (2019, p. 8) assumes that consumers will distance themselves from living at a fast pace and engaging in excessive consumption, moving towards slow and minimalist consumption, which focuses on sustainability, protection and functionality. Due to the role of food in the human hierarchy of needs, it is worth paying attention to three main trends related to the food and drink market. They include Elevated Convenience, Evergreen Consumption and Through the Ages. It appears that comfort is of particular importance in today’s busy world. Apart from convenience, consumers expect naturalness, a high level of nutritional value and personalisation possibilities, as well as an element of surprise and new experiences. The second trend-Evergreen Consumption-focuses on the idea of a circular economy, indicating opportunities for close cooperation focussed on sustainable development between suppliers, producers, commercial networks and consumers, as well as governmental and non-profit organisations. In turn, the third trend-Through the Ages-focuses on the role of food and drink in the process of supporting active and healthy ageing. At this point, it is worthwhile to mention freeganism, which, at present, may be seen as a form of a widespread boycott of excessive consumption. Many freegans, in addition to expressing socio-economic contestation, point to the importance of ecological problems by leading an environmentally friendly lifestyle (Wyrębska, 2014).

Changes in consumers’ lifestyles, purchasing and consumption behaviours aimed at greening consumption require appropriate competence. Young people, in particular, should expect brands to support their health and well-being, as well as their greater involvement in their education and development as socially responsible consumers.

Social Responsibility of Modern Consumers for the Greening of Consumption

As emphasised by Kiełczewski (2001), the fight against the crisis related to the natural environment is closely related to individual responsibility and ecological conscience. Changing the person’s approach towards nature should consist in shaping an ethical and empathic attitude towards the surrounding world, with the individual, daily decisions of each of us lying at its core.

The purchase of organic products by modern consumers can result from two motives. These can be altruistic reasons that relate to caring for the environment and social considerations or egoistic reasons associated with focussing on the consumers’ own safety-maintaining good health, condition and well-being by purchasing better quality products, organic products, especially food, clothing and footwear, cosmetics and cleaning supplies.

Recently, consumers have been urged to limit and minimise consumption, which can be treated as a way to counteract consumerism (Patrzałek, 2022). The social responsibility of consumers has many dimensions. The latter does not refer merely to responsible shopping. Social responsibility is also associated with our general behaviour, e.g. buying only the items that we actually need, not getting rid of these products after a short period of time or not being influenced by advertisements or commercials, discounts and other economic and non-economic incentives to buy newer and newer models or brands.

The aspect that draws our attention when observing consumer behaviour on the organic products market is the visible inconsistency, i.e. the discrepancy between positive attitudes towards ecological products and consumers’ purchasing practices. This tendency is indicated by numerous studies. Despite the willingness of consumers to pay higher prices (77%), only 13% of respondents make purchases of ecological products during the month preceding the survey (with the exception of Denmark and Sweden, where the share amounted to 40%) (Witek, 2018). This specific discrepancy between consumers’ attitudes and their behaviours on the organic market is reflected in Young et al. (2009)’s study, which indicated that 30% of consumers declare their concern about environmental issues, but this is not sufficiently reflected in market behaviour, as their actual organic food purchases reach the level of 5% of sales.

Such discrepancies, known as the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’, ‘green-gap’ or ‘words-deed gap’, had been widely discussed in literature providing various conceptualisations of the topic, but no consensus has been reached so far. Numerous groups of factors potentially causing the ‘gap’ were named, encompassing: (1) research biases, especially social desirability or sample selection biases; (2) external and internal inhibitors of green consumption, such as unreasonable prices in the first case and insufficient environmental knowledge in the second; and (3) consumers’ scepticism or cynicism. As proposed by Shaw, McMaster and Newholm (2016), referring to the theory of ‘Four phases of caring’ by Tronto (1993), the distinction between ‘desire’ and ‘act’ can be seen as the pivotal issue in ‘attitude-behaviour gap’ in the case of ethical consumption, which also includes pro-environmental consumption. An interesting approach to the problem of ‘green-gap’ was presented by Johnstone and Tan (2015), in which three main barriers to internalisation of green purchase behaviour by consumers were pointed out. The qualitative study covering seven focus groups revealed that the major obstacles from the perspective of the interviewed participants are: the perceived unattainability of green consumption activities due to limited time and money resources, or the belief that individual efforts are pointless if others do not co-operate. The so-called ‘green stigma’, which consists in rationalising the non-green consumer behaviour as an act of self-esteem and self-identity defence mechanism, appears to be of no less importance. We should also mention the ‘green reservations’ whereby consumers do not seem to perceive the greening of everyday activities as an urgent need or a social norm.

The green consumer is typically known as one who supports eco-friendly attitudes and/or who purchases green products over the standard alternatives (Boztepe, 2012). However, referring to Blustein’s argument (1991) that ‘there can be care without commitment, but there cannot be commitment without care’ and taking into consideration the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’ phenomena, it is worth considering whether the use of the conjunction ‘or’ in the definition proposed above might be justified. As recommended by Zbuchea (2013), more focus in further research should be placed on actual consumer behaviour.

The social responsibility of consumers must be expressed by opposing all those who damage the environment. This objection can be manifested through consumer boycotts, organising or participating in campaigns stigmatising actions that are harmful to the environmental, engaging in protests or ecological sabotage (Dąbrowska & Janoś-Kresło, 2022).

Through their choices and behaviours, consumers influence the shape of modern production, and they may be perceived as the driving force behind the development of the trend called the greening of consumption. As mentioned in the introduction of the article, the needs and tastes of buyers set the direction for market changes. Increasingly, consumers dictate to entrepreneurs what will be produced, not the other way around, and these consumers seem to take the social responsibility related to consumption very seriously, and one of the dimensions of such responsibility is ecological responsibility.

Celebrities can play a significant role in creating a sense of social responsibility in consumers, becoming a role model through shaping the tastes and behaviour of society (Furedi, 2010).

Corporate Social Responsibility for the Greening of Consumption

In the literature on the subject, there are many definitions of corporate social responsibility (CSR) (Zbuchea, A., & Pînzaru, F. (2017). The European Commission has defined CSR (Corportate Social Responsibility) as the responsibility of enterprises for their impact on society and, therefore, it should be company-led. Companies can become socially responsible by integrating social, environmental, ethical, consumer and human rights concerns into their business strategy and operations following the law (Porter, Kramer, 2006). According to the ISO (International Organization for Standardization: 26000:2010 standard, social responsibility is implemented as a course of transparent and ethical behaviours aimed at ensuring sustainable development, health and social well-being. It also takes into account the expectations of stakeholders in accordance with the applicable law and international standards of behaviour. It is also consistent with the organisation as well as implemented and practiced in its relations. CRS provides guidance for all types of organisations, regardless of their size or location (ISO, 2018). The concept of CSR emphasises the importance of relations with stakeholders and covers three aspects of corporate operations, i.e. its economic, social and ecological activities.

As illustrated by Zbuchea (2013), there is a positive relationship between CSR and consumer loyalty. On the one hand, consumers tend to reward companies that are socially and environmentally responsible, which is reflected in the level of trust, advocacy and purchasing behaviour. On the other hand, they boycott companies that act irresponsibly, not to mention the ones that engage in so-called ‘greenwashing’. In spite of such unfair practices being implemented by some companies, people generally put trust in CSR initiatives. Thus, environmentally driven strategies could be seen as an important part of building a competitive advantage and as a token of credibility.

According to Cherian and Jacob (2012) there have been a total of various circumstances that are influential in encouraging green consumers to buy green products. Far-reaching research over the years has, among other positive effects, generated an immense understanding concerning green issues; heightened the level of knowledge opportunity on environmental subsistence; encouraged major corporations to opt for green advertising; raised concern for the environment; and expanded recognition of green products by environmental and social charities. This overpowering increase in general ecological awareness among various consumer groups is correlated with the companies’ initiatives to ‘go green’ that has followed the introduction of the idea of corporate environmentalism into the mainstream public consciousness.

In this context, we may notice that there occurs mutual dependence between socially sensitive enterprises and socially sensitive consumers. Business entities can create the needs of consumers by offering proecological products as well as marketing activities that educate individuals and build consumer awareness. At the same time, consumers can force enterprises to engage in appropriate pro-ecological actions and behaviours. Johnstone and Tan (2015) stress that companies’ efforts should be focussed on changing consumers’ perceptions of green products and green activities from unattainable and hard-to-achieve to easy and non-exclusive, as well as focussing on reducing consumers’ scepticism and cynicism if they occur. The research conducted by Accenture in cooperation with United Nations Global Compact (2014) revealed that providing customers with tangible responsibility outcomes would lead the consumer to behave in a manner consistent with sustainable values on the one hand, and on the other, as shown by Hoogendoorn et al. (2015), direct contact with consumers influences SMEs (Small and Medium-sized Enterprises) to offer green products. So does the legislation.

According to the ‘Green Generation’ (Chamber of Electronic Economy 2020) report, 75% of the surveyed Polish companies include the concept of ecology in their strategies and plan to undertake activities supporting environmental protection. An example of a legislative measure mandating an environmental vanguard action is the so-called Single-Use Plastic (SUP) directive, adopted by the European Parliament, according to which all plastic bottles will have to be made in a minimum of 25% from recycled material by 2023 at the latest, and 30% in 2030. As much as 96% of the surveyed companies believe that brand activities can have an impact on changing consumer behaviour, and they may result in a conscious shopping approach or in undertaking actions to protect the environment on a daily basis. In turn, environmentally sensitive consumers should limit the purchase of products in plastic packaging, and they ought to select products made from recycled PET (Politereftalan etylenu) bottles and sort waste.

The Importance of Competences in Changing Consumer Behaviour

The increasing and changing offer of consumer goods and services, which is also a result of globalisation, virtualisation and greening, as well as the shortening of the product life cycle, necessitates researchers and business practitioners to pay greater attention to the requirements of environmentally conscious consumers. Competent consumers should oppose the negative trend of consumerism, i.e. excessive buying, rationalise their market decisions, save time and the environment, and thus protect their own health and those of other consumers. The greening of consumption is most often equated with positive consumer attitudes towards the natural environment and increasing environmental awareness. Many authors associate eco-consumption with the direct response, expressed principally in the form of purchasing choices, arising from buyers’ understanding of the detrimental human impact on the environment attributable to excessive, burdensome and wasteful consumption.

Pro-ecological attitudes and behaviour may be regarded as a consequence of high consumer competences. Analysing the definitions of consumer competences in the literature on the subject, it can be seen that a significant proportion of researchers perceive them from an economic perspective. The authors suggest that the powers of the consumer competence are based on the economic capacity to buy goods and services, as well as the skills, attitudes and knowledge related to the rational approach to consumption and a sceptical attitude towards marketing and advertising communications (for example Royer & Nolf, 1980; John, 1999; Gronhoj, 2004; Lachance & Choquette-Bernier, 2004). Other representatives emphasise the complexity of the concept of consumer competence, indicating that it is a concept consisting of cognitive, behavioural and information dimensions (Lachance & Legault, 2007, p. 1–5; Cloutier, 2014). Consumer competences are also associated with attitudes (Lachance & Legault, 2007, p. 1–5; Berg & Taingen, 2009) and the functioning of the consumer in social structures (Ekopolityka. Polityka ekologiczna w Polsce i na świecie).

Thierry, Sauret and Monod (1994) define competencies as ‘all knowledge, ability to act and attitudes forming a whole depending on the goals and circumstances of specific actions’. Dąbrowska et al. (2015, p. 54) perceive consumer competences as ‘theoretical knowledge and practical skills which help a person meet the lower and higher needs efficiently and effectively, taking responsibility for the choices and decisions made without compromising their expectations concerning quality.’

Research on consumer competences has enabled the identification of a competent consumer of the future. It will be a person who is increasingly aware and possesses knowledge about products and is generally familiar with the production process. This individual will consume more and more, and products available on the market will have a shorter and shorter life cycle. The market and consumers will be divided into sectors according to their material and financial standing. Consumers will strive for self-sufficiency and ‘create ecovillages’ that will use e-services on a mass scale, and products will be further unified (Dąbrowska et al., 2015, p. 104–105).

Frequently, growing ecological awareness is related to food products. Consumers are increasingly keen to reach for local and traditional products, whose quality is related to the production area and its natural, geographical and cultural specificity (regional products). They often opt for ecological and organic products, i.e. food produced without the addition of artificial fertilisers or pesticides. Such a natural way of cultivating soil allows maintaining soil fertility and biological diversity, which is also associated with greater care for the environment in consumption acts. (Dąbrowska & Janoś-Kresło, 2017, p. 5–34). It is worth emphasising that the importance of social consumer competence manifests itself in particular in food consumption (Bylok, 2014, p. 30–42).

According to many European consumers, the high prices of organic food significantly limit consumer interest in purchasing it (Magnuson et al. 2001). This tendency was also confirmed by the findings of the survey carried out among Polish consumers (Dąbrowska & Janoś-Kresło, 2017, p. 32).

Consumer competence and environmental awareness are not the only determinants of consumer choice in terms of organic products. Ecological consumer behaviour can be motivated by, inter alia, governmental activities, activities of consumer movements and broadly perceived sociocultural changes (Dąbrowska et al., 2015, p. 148–173). The social responsibility of consumers also plays an important role in this regard.

Materials and Methods

The purpose of the study was to identify shopping preferences and selected consumer behaviours pertaining to the purchase of ecological/organic food products. The scope of the study, the number of questions and their form and wording, as well as the order of questions, were agreed upon as part of content-related consultations. The CAWI interview questionnaire was prepared using CADAS software to better visualise the questions and make online interviews more attractive, especially in the case of questions using the scale. The survey was conducted in Poland during Sep. 15–27, 2021, with the application of the CAWI technique and using online panels as part of the Omnibus survey. The interview questionnaire consisted of three sets of questions, as well as filtering questions and demographic data. The set of questions concerning ecological/organic food products consisted of four questions, including one demographic question (assessment of statements using a scale), two single-choice questions and one question with the option of indicating more than one answer. The filtering questions included five questions related to the respondents’ gender, age, education and their place of residence. Additional demographic questions were six questions characterising the respondent’s household.

The average time to answer all the questions of the omnibus study (three different question sets) was just over 6 min (6 min and 3 s). A total of 1,980 panellists responded to the request to complete the survey, out of which N = 1,000 respondents qualified for the survey and answered all the questions (success rate 50.5%). N = 980 respondents were not qualified for the study or were rejected at the control stage due to contradictory answers to the control questions, illogical answers to open and semi-open questions, refusal to participate in the study or failure to meet the criteria of filtering questions. The last group of survey participants not qualified for the study received remuneration for their willingness to participate in the study.

The ABR SESTA Institute implemented the control procedure in accordance with the ESOMAR and PTBRIO (Polskie Towarzystwo Badaczy Rynku I Opinii; ang. Polish Society of Market and Opinion Researchers standards and prepared collective result tables. The responses collected from the respondents were subject to control procedures consisting of several steps. The elements that were verified included, among others, the time it took to complete the survey questionnaire and the consistency and logic of the responses. The questionnaires that were filled in too fast or without due care were rejected. The control questions were also used in the survey questionnaire, i.e. the respondents were asked about the device used to complete the questionnaire. The responses of the survey participants who gave contradictory responses have been removed. In addition, a qualitative assessment of the responses was made. It included, among others, the analysis of answers to open-ended and semi-open questions. The respondents’ responses were arranged in interactive result tables prepared using Excel software. To determine whether the observed differences are statistically significant, Bonferroni tests were performed. The Bonferroni test is a statistic that compares all pairs of the independent variable with the Student’s t test while controlling the number of comparisons. The returned significance of differences between the groups includes a correction for the number of comparisons made. It produces more accurate results when there are few comparisons between pairs of measurements or groups. The Bonferroni test is used when the assumption of equal variance is satisfied.

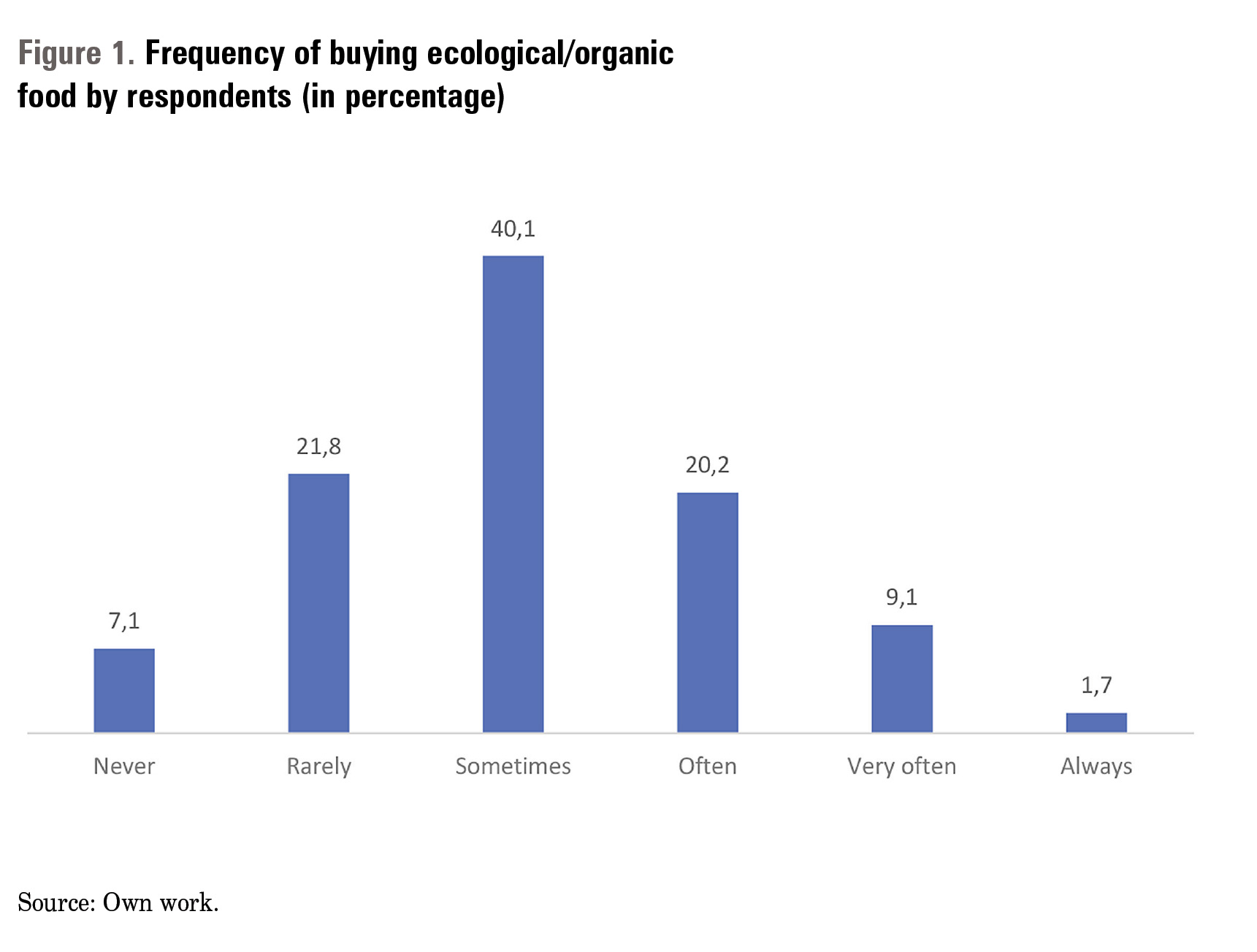

The boundary amounts for gender, age and size of the place of residence were maintained in the study. The sample distribution is presented in Table 1.

Results

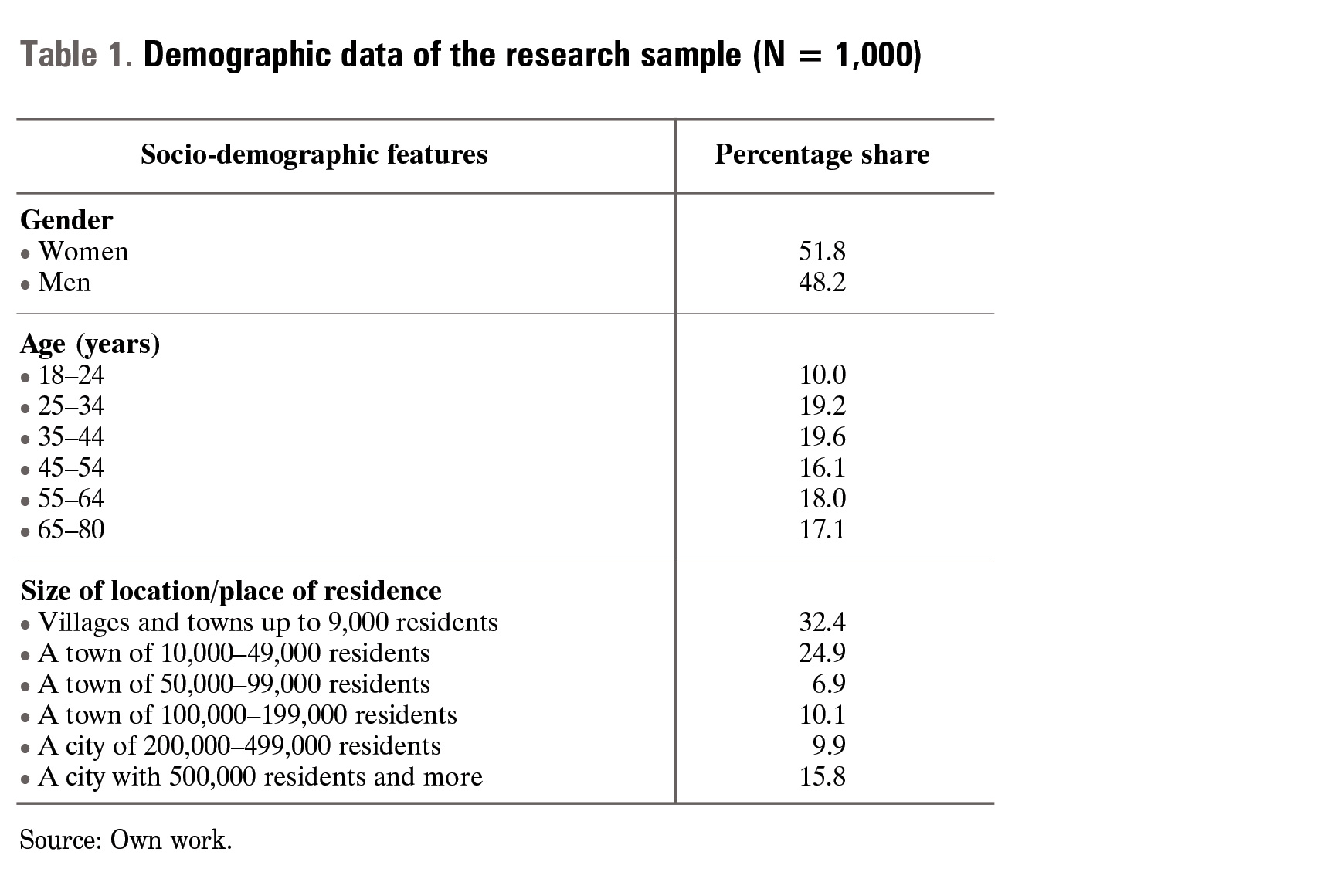

Food is considered the basis of human existence as it satisfies physiological needs. A new trend in consumption, i.e. taking care of health, prompts consumers to look for products with specific nutritional values. Such products include organic food produced with the use of ecological farming methods, without the use of pesticides and artificial fertilisers. Ecological/organic food includes fresh produce, meat and dairy products, as well as processed foods such as frozen meals. The respondents were asked whether they were buying organic products when buying food to satisfy the needs of their household. The frequency of making such decisions varied. More than every 10th respondent (10.8%) declared that they always or very often buy ecological/organic food products, while 7.1% never did so (Figure 1).

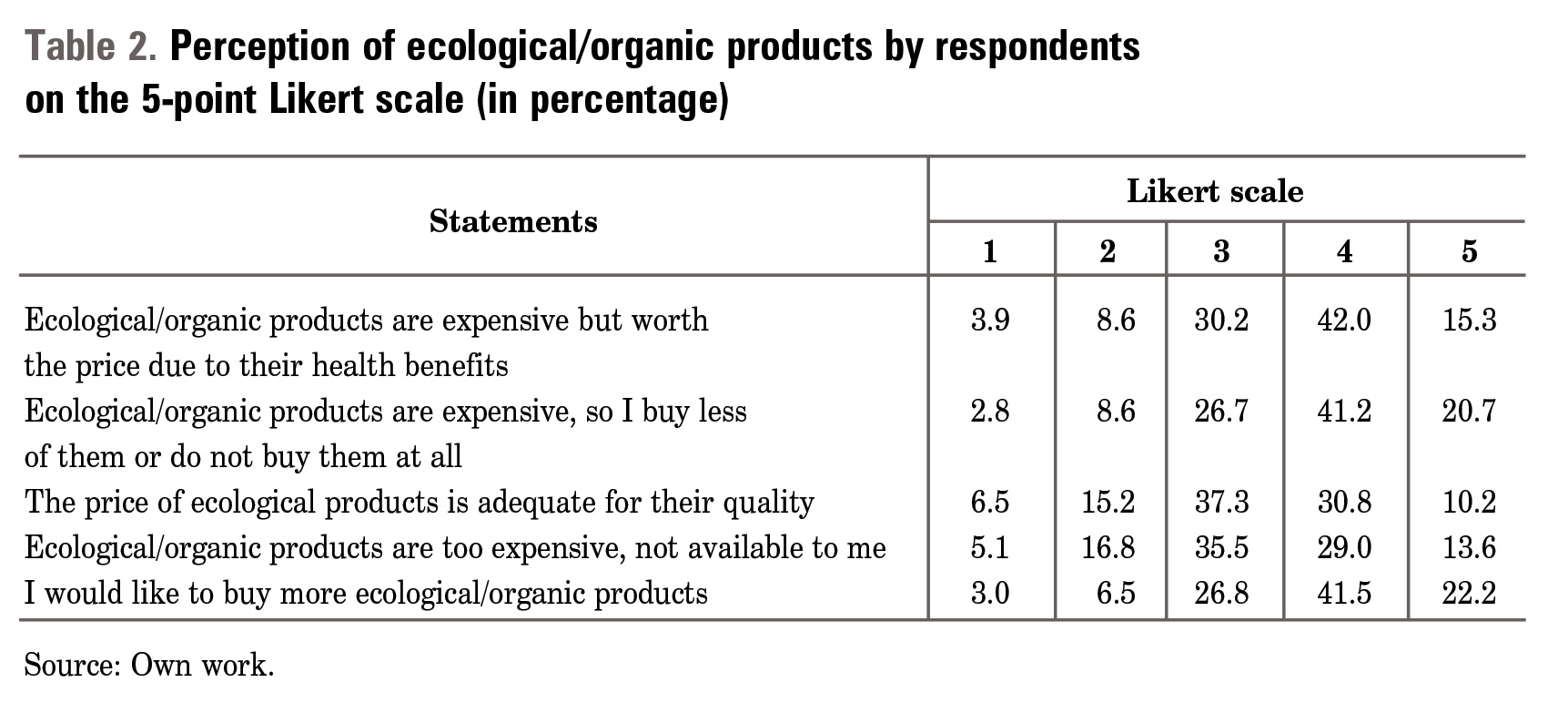

Ecological/organic products are perceived differently by consumers, and thus respondents were asked to comment on the following statements. For this purpose, a 5-point Likert scale was used, where 1 represented the response ‘I strongly disagree’ and 5 ‘I strongly agree’ (Table 2).

A total of 57.3% of respondents strongly (‘definitely yes’ and ‘rather yes’) agreed with the statement that organic products are expensive but worth the price due to health benefits, which indicates the continual availability of these products in regions where there is a sustained demand for them.This opinion was confirmed by the responses to the second statement that ‘organic products are expensive, so I buy less of them or do not buy them at all’. A total of 61.9% of Poles agreed with such a claim. Nevertheless, 41.0% of respondents believed that the price of organic products corresponded with their quality. It appears that the high prices of organic products make them inaccessible to many consumers. Such an opinion was expressed by 42.6% of respondents. Unaffordability causes consumers to be unable to meet their actual demand. As much as 63.7% of Poles would like to buy more organic products. Perceiving the prices of ecological/organic products as high can justify the behaviour of consumers who buy ecological/organic products when they are available for sale at discounted prices (61.3% of the responses including ‘definitely yes’ or ‘rather yes’).

The statements above were analysed in terms of the answer ‘definitely yes’ according to the socio-demographic characteristics of the respondents and using Bonferroni’s tests.

The statement ‘organic products are expensive, but worth the price due to health benefits’ was more frequently indicated by women (16.4%) than men (14.1%), people aged 35–44 years (20.9%), people with lower secondary education or less (18.2%), people living in the city with more than 200,000 up to 499,000 residents (22.2%), and those coming from households of four people (20.5%). There were no statistically significant differences. The statement ‘organic products are expensive, so I buy less of them or do not buy them at all’ was chosen by both women (21.2%) and men (20.1%), people aged 45–54 years (23.6%), and people with education at a secondary (20.6%) or higher level (21.4%). People living in a city with more than 500,000 residents (30.4%) also indicated it statistically significantly more frequently than in a city with 50,000–99,000 residents (11.6%) and people living in a single-person household (25.3%).

No significant differences were observed in terms of gender or age with respect to the statement ‘the price of organic products is adequate for their quality’, except for the lowest and highest groups. This opinion was more common among respondents with lower secondary education (13.6%), people living in towns with 100,000–199,000 residents (15.8%) and individuals from three-person households (13.7%).

In the case of the statement ‘organic products are too expensive, not available to me’, men (16.4%) agreed more often than women (11.0%) and it was a statistically significant difference. This response was also selected by people aged 45–54 years (16.1%), people with secondary or post-secondary education (14.7%), people living in the town with 100,000–199,000 residents (16.8%) and persons from single-person households (22.7%).

More women (25.3%) than men (18.9%) would like to buy more ecological/organic products more often (this is a case of a significant statistical relationship). The same claim was also selected by people in the 34–45-year age group (29.1%, statistically significantly more often than people in the 65–80-year age group-9.9%), people declaring lower secondary education level or below (27.3%), those living in a town with 200,000–499,000 residents (33.3%, statistically significantly more often than in towns of up to 9,000 residents — 18.5% and 10,000–49,000 residents — 16.1%), and those coming from four-person households (27.4%, statistically significantly more often than from two-person households — 15.6%).

Based on the data obtained, a profile of the average Pole, who often buys ecological/organic food products, was created. The created profile includes the following characteristics: it is a woman, aged 35–44, with a higher education level, living in a town with 200–499,000 residents and from a four-person household.

Conclusion

Awareness in the context of sustainability can be explained on two general levels. The first and oldest one is ecological awareness, also called environmental awareness, which means to be aware of the human impact on the environment, to feel responsible about the Earth and to take care of the so-called ecological issues (Naess, 1973). The higher and more general level is known as sustainability awareness, which — following the definition of sustainability — includes not only environmental but also socio-economic issues. This approach is now more often used and implemented as more suitable for solving (or rather trying to solve) contemporary world problems (Machnik & Królikowska-Tomczak, 2019). These considerations are regarded as particularly timely and appropriate in view of increasing environmental disasters, including those occurring in Poland.

Consumers usually experience no problem as far as deciphering the term ‘ecological’ or ‘environmentally friendly’ is concerned. This term is most frequently understood by individuals who care for the Earth, live in accordance with the laws of nature, do not litter, segregate waste, save electricity and water, use reusable paper bags rather than plastic ones, do not disturb the balance of the environment, pay attention to what they buy and how they use it, prefer organic food and ecologically friendly automobiles, and actively participate in the environmental movements. In Poland, 56% of Poles believe that ecology is a conscious choice, a sense of responsibility and an attitude that does not pass, while the remaining 44% is of the opinion that this is the current fashion that will soon be forgotten (Ekopolityka. Polityka ekologiczna w Polsce i na świecie).

However, when observing the changes taking place in the natural environment, the inference emerges that knowing the concept is not enough in itself. We need to change our approach and perception of the phenomenon, from a short — to long-term perspective and apply the five principles of zero waste, namely: Refuse, Reduce, Reuse, Recycle and Rot (Izba Gospodarki Elektronicznej, 2020, p. 24–26). Collaborative consumption, also known as sharing consumption or collaborative consumption, can play an essential role in this context. The concept refers to the tradition of sharing goods, exchanging them, borrowing, renting and donating, and modern technology and the development of the information society assign a new meaning and a new role to this concept (Dąbrowska & Janoś-Kresło, 2018, p. 132–149).

The social responsibility of modern consumers can be viewed from the perspective of COVID-19 (coronavirus disease 2019). In the era of the coronavirus pandemic, our consumer decisions made during everyday purchases can be seen as decisive, which might affect the fate of people, the economy and the environment and which can support charitable activities and the local market and enterprises. The consumer’s inalienable right is the right to choose, and the conscious exercise of this right is associated with a responsibility for purchasing decisions and their effects. The uncertainty of the pandemic situation means that many consumers stock excessively, and this is especially the result of alluring offers made by large shopping networks and e-commerce websites. Excessive purchases of food, in particular, can lead to its wastage, and thus to the waste of resources, energy, water, etc., which are perceived as increasingly limited resources. Perhaps it is under such circumstances that it becomes particularly important to ask oneself the following questions: ‘What are the products that I wish to buy made up of and how were they created?’; ‘Who produced them and in what conditions, and how do their use and utilisation affect the natural and social environments?’ It is also worth remembering that according to the report of the International Ecological Organization (WWF, 2019), members of the European Union use almost 20% of the Earth’s biological potential. In addition, if every inhabitant of the planet consumed the same amount as an average resident of the EU, 2.8 planets would be needed to regenerate the ecosystem. This value greatly exceeds the world average, which is estimated at about 1.75 of the Earth.

Both consumers and business entities should behave in a responsible manner. As Jonas (Greisch, 1992, p. 105–105) notes, responsibility as a positive duty turns out to be, in essence, driven by the feeling of ‘the sense of being responsible’. As Kotler (2010) observes, the modern consumer has gained a soul, and the goal set by the enterprise is to make the world a better place. The passage from material consumption to non-material consumption, and also from instrumental values to autotelic values connected with observing the right of all living creatures to a dignified life respecting their well-being, constitutes the indicators of the new model of society (Patrzałek, 2019).

If deconsumption might be seen as a permanent trend in the development of modern consumption (Bylok, 2017), perhaps Bauman’s words are still valid (1998) ‘…to become a fully feathered and full-fledged member of society, you need to efficiently and effectively respond to the excitement and the temptation of the consumer market’.

Every consumer and every entrepreneur needs to answer the questions about what matters to them, and which values they consider to be their priorities.

In the context of the above considerations, relevant conclusions can be drawn.

The concept of ecological consumption, similar to the one of a responsible consumer or a responsible enterprise, is evolving. It not only focuses on environmental issues, but also covers much broader issues, such as returning to our ‘green’ roots, climate change and social responsibility. Households have a significant impact on the environment through consumption: energy, food, transportation, water and waste production (OECD, 2014; Manson, 2018).

First of all, one should be aware that ecological consumption concerns all generations, although sensitivity to ecology may vary in societies. Only joint activities supported by education and building proper competencies facilitate achieving the set goals. This is especially important if we consider the above-mentioned results of the study, which indicate that in Poland only 31% of Internet users are interested in the condition of the natural environment, and 44% of them consider Poland to be an ecologically endangered area.

Apart from governments and state institutions, the main role in shaping pro-ecological attitudes is played by consumers and enterprises offering goods and services on the market (Kuokkanen, Sun, 2016). The changes in attitudes, purchasing behaviour, values and everyday habits that would be required to initiate the transition of a consumer from consumption characterised by an attitude of apathy for the ecological situation to one by concern can be effected through involving them in programmes benefitting the environment, and the success with which these are implemented depends upon their scale and reach. It is worth remembering that regardless of the social and professional roles played, each of us is still a consumer.

Businesses and consumers create mutually dependent relations. Therefore, consumers should demand green goods and services from enterprises and, as prosumers, they should expect companies to implement practical and environmentally friendly solutions. Brands should increasingly undertake eco-initiatives. In formulating marketing campaigns to inform consumers about the product, the business should ensure that the message that is prepared for this purpose strongly explains not only the features and composition of the product but also whether it has been manufactured in an environmentally sustainable manner; this will enable the consumer to judge whether they are going to purchase environmentally friendly and ethical products. It is necessary to carry out more information — and education-based activities in line with the concept of sustainable consumption.

The survey of consumer attitudes towards organic products was conducted using the CAWI technique because of the ease and speed of reaching potential respondents, and because respondents are reached within a reasonable budget. The limitation of this technique is that we do not reach people who are not using the Internet. On the other hand, the number of people who do not use the Internet in Poland is decreasing year by year, and the CAWI technique is gaining popularity, due to the large number of potential respondents. ABR SESTA, through its cooperation with SYNO Poland, offers access to more than 1.8 million potential respondents to the CAWI technique in Poland. This allows us to more easily profile respondents and more easily map the structure for a representative sample.

As consumers, we are marked by constant change. Consumers and businesses operate in uncertain times, times marked by critical events. Therefore, it is important to repeat the survey at intervals of no less than 12 months in order to observe possible changes in consumer behaviour and business actions. Changes in consumer behaviour can be the result of producers’ actions or lack of producers’ actions. Keeping the survey cyclical will make it possible to observe these changes and make inferences based on them. What is important in cyclical measurements is the use of an unchanged methodology.

The authors regard this article as a contribution towards the furtherance of discussions and research on significant and topical issues connected with CSR.

References

1. Bauman, Z. (1998). Zbędni, niechciani, odtrąceni-czyli o biednych w zamożnym świecie (transl. Redundant, unwanted, rejected-that is, about the poor in the rich world). Kultura i Społeczeństwo, 2, 9.

2. Berg, L., & Teigen, M. (2009). Gendered consumer competences in households with one vs. two adults. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 33(1), 31–41.

3. Bocking , S. (2009). Environmentalism. The Cambridge History of Science, 6, 602–621.

Retrieved from https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/cambridge-history-of-science/environmentalism/ D4C45360C185F46359A31BFECA4E4ECA (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

4. Boztepe, A. (2012). Green marketing and its impact on consumer buying behavior. European Journal of Economic and Political Studies, 1, 5–21. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/288525147_Green_Marketing_and_Its_Impact_on_Consumer_Buying_Behavior (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

5. Bylok, F. (2014). Wybrane społeczne kompetencje konsumenckie Polaków w świetle badań (trans. “Selected social consumer competences of Poles in the light of research”). Handel Wewnętrzny, 4(351), 30–42.

6. Bylok, F. (2017). Intricacies of modern consumption: Consumerism vs. Deconsumption. Annales Ethics in Economic Life, 20(8), 61–74. doi:10.18778/1899-2226.20.8.06(Last accessed on May 13, 2020)

7. Cherian, J., & Jacob, J. (2012). Green marketing: A study of consumers’ attitude towards environment friendly products. Asian Social Science, 8, 117–126. Retrieved from http://www.ccsenet.org/journal/index.php/ass/article/view/20767 (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

8. Cloutier, J. (2014). Competence in consumer credit products: A suggested definition. The Forum for Family and Consumer, (19). Retrieved from https://www.theforumjournal.org/ 2014/04/01/competence-in-consumer-credit-products-a-suggested-definition/ (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

9. Dąbrowska, A., Bylok, F., Janoś-Kresło, M., Kiełczewski, D., & Ozimek, I. (2015). Kompetencje konsumentów. Innowacyjne zachowania, zrównoważona konsumpcja (transl. Consumer competences. Innovative behavior, sustainable consumption). Warszawa: PWE.

10. Dąbrowska, A., & Janoś-Kresło, M. (2017). Polish consumer on the traditional and regional food market. Lambert Academic Publishing.

11. Dąbrowska, A., & Janoś-Kresło, M. (2018). Collaborative consumption as a manifestation of sustainable consumption. Problemy Zarządzania-Management Issues, 16, 132–149. Retrieved from http://cejsh.icm.edu.pl/cejsh/element/bwmeta1.

element.desklight-6f6a9e4e-36ee-4419-97f0-75698a6f67cc (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

12. Dąbrowska, A., & Janoś-Kresło, M. (2022). Społeczna odpowiedzialność konsumenta w czasie pandemii. Badania międzynarodowe. Warsaw: SGH (Warsaw School of Economics).

13. Daly, H. F. (2007). Ecological economics and sustainable development. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited: 14. Retrieved from http://library.uniteddiversity.coop/Measuring_ Progress_and_Eco_Footprinting/Ecological_Economics_and_Sustainable_Developme nt-Selected_Essays_of_Herman_Daly.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

14. Ekopolityka. Polityka ekologiczna w Polsce i na świecie (transl. Ecopolitics. Ecological policy in Poland and in the world). Retrieved from https://ekopolityka.pl/zero-waste (Last accessed on May 13, 2020)

15. European Parliament. (2018). Plastik w oceanach: fakty, skutki oraz nowe przepisy UE (transl. Plastic in the oceans: Facts, effects and new EU rules). Retrieved from https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/pl/headlines/society/20181005STO15110/plastik-w-oceanach-fakty-skutki-oraz-nowe-przepisy-ue (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

16. Furedi, F. (2010). Celebrity culture. Society, 47(6), 493–497. Retrieved from https://go.gale.com/ps/anonymous?id=GALE%7CA359998827&sid=googleScholar&v =2.1&it=r&linkaccess=abs&issn=01472011&p=AONE&sw=w (Last accessed on

May 13, 2020).

17. Greisch, J. (1992). Od Gnozy do zasady odpowiedzialności. Rozmowa z Hansem Jonasem (transl. From Gnosis to the principle of responsibility. An interview with Hans Jonas. Literatura na świecie, 7, 105–106.

18. Gronhoj, A. (2004). Young consumers competences in a transition phase: Acquisition of durables and electronic productsIn Colloque international organisé par le centre Européen des Produits de L’Enfant, Le Centre Européen des Produits de L’Enfant, 707–725 (CD-ROM). Conference: Pluridisciplinary perspecitives on child and teen consumption, 25 Mar 2004 — 26 Mar 2004, Angouleme, Université de Poitiers

19. Izba Gospodarki Elektronicznej. (2020). Raport green generation 2020. Mobile Institute. Retrieved from https://eizba.pl/wp-content/uploads/2020/01/GreenGeneration_ WspolnieNaRzeczZiemi.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

20. John, D. R. (1999). Consumer socialisation of children: A retrospective look at twenty-five years of research. Journal of Consumer Research, 26, 183–213.

21. Johnstone, M. L., & Tan, L. P. (2015). Exploring the gap between consumers’ green rhetoric and purchasing behaviour. Journal of Business Ethics, 132(2), 311–328.

22. Kiełczewski, D. (2001). Ekologia społeczna (transl. Social ecology). Ekonomia i Środowisko.

23. Kotler, P. (2010). Marketing 3.0. MT Biznes .

24. Kuokkanen, H., & Sun, W. (2016). Social desirability and cynicism: Bridging the attitude-behavior gap in CSR surveys. Research on Emotion in Organisations.

Emerald, pp. 217–247.

25. Kurenlahti, M., & Salonen, A. O. (2018). Rethinking consumerism from the perspective of Religion. Sustainability 10(7). Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/ publication/326421527_Rethinking_Consumerism_from_the_Perspective_of_Religion (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

26. Lachance, M. J., & Choquette-Bernier, N. (2004). College students’ consumer competence: A qualitative exploration. International Journal of Consumer Studies, 28(5), 433–442.

27. Lachance, M. J., & Legault, F. (2007). College students’ consumer competence: Identifying the socialization sources. Journal Research for Consumers, 13, 1–5.

28. Machnik, A., & Królikowska-Tomczak, A. (2019). Awareness rising of consumers, employees, suppliers, and governments. In W. Leal Filho, A. Azul, L. Brandli, P. Özuyar, & T. Wall (Eds.), Responsible consumption and production. encyclopedia of the UN sustainable development goals (pp. 22–36). Springer Nature. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007%2F978-3-319-95726-5_39.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

29. Manson, J. (2018). From ‘evergreen consumption’to ‘elevated convenience’the food and drink trends that will shape 2019. Retrieved from https://www.naturalproductsglobal.com/food-and-drink/from-evergreen-consumption-to-elevated-convenience-the-food-and-drink-trends-that-will-shape-2019/ (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

30. Meadows, D. H., Meadows, D. I., Randers, J., & Behrens, III. W. W. (1972). The limits to growth. A report to the club of rome (1972). Abstract established by Eduard Pestel. Retrieved from https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~wggray/Teaching/His300/Illustrations/Limits-to-Growth.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

31. Mintel. (2018). Europejskie trendy konsumenckie 2018 (2018 European consumer trends). Retrieved from https://polska.mintel.com/europejskie-trendy-konsumenckie (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

32. Mintel 2030 Global Consumer Trends. (2019). (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

Mintel.com

33. Naess, A. (1973). The shallow and the deep. Long range ecology movement. Inquiry, 16, 95–100. Retrieved from https://iseethics.files.wordpress.com/2013/02/naess-arnetheshallow-and-the-deep-long-range-ecology-movement.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

34. OECD (2014). Greening Household Behaviour. A Review for Policy MakersOECD Environment Policy Paper. Retrieved from https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/environment/ greening-household-behaviour_5jxrcllp4gln-en (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

35. Patrzałek, W. (2019). Between consumerism and deconsumption — In search of a new model of society. Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu (Research Papers of Wrocław University of Economics and Business), 63(10), 221–234. doi:10.15611/pn.2019.10.16

36. Patrzałek,W. (2022). Konwestycja jako forma dekonsumpcji. Wrocław: The Publishing House of the University of Wrocław.

37. Porter, M. E., & Kramer, M. R. (2006). Strategy and society. The link between competitive advantage and corporate social responsibility. Harvard Business Review December, 2006, 78–93. Retrieved from https://www.sharedvalue.org/sites/default/files/resource-files/Strategy_and_Society.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

38. Rock, F. J. (2010). Green building — Trend or megatrend? Dispute Resolution Journal, 65, 72–77.

39. Royer, G., & Nolf, N. (1980). Education of the consumer: A review of the historical development. Consumer Education Resource Network.

40. Shaw, D., McMaster, R., & Newholm, T. (2016). Care and commitment in ethical consumption: An exploration of the ‘attitude-behaviour gap’. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(2), 251–265.

41. The European Environment — State and Outlook 2010. (2010). Consumption and the environment. Office of the European Union. Luxembourg. doi:10.2800/58407

42. Tronto, J.C. (1993). Moral Boundaries. A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care. Edition 1st Edition First Published. eBook Published 25 July 2020, Pub. Location New York, Imprint Routledge, DOI https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003070672

43. Trocki, M., & Wachowiak, P. (2019). Rozwój koncepcji zrównoważonego rozwoju i społecznej odpowiedzialności (transl. Development of the concept of sustainable development and social responsibility) In M. Trocki (Ed.), Społeczna odpowiedzialność działalności projektowej (pp. 23–57). SGH (Warsaw School of Economics).

44. United Nations. (1969). Problems of the human environment, United nations economic and social council. New York, NY and Geneva, 6 August 1969. Retrieved from https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/214596?ln=en (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

45. Witek, L. (2018). Postrzegana wartość´ produktu ekologicznego a rzeczywiste zachowania konsumentów (transl. Perceived value of an ecological product and actual consumer behavior). Prace Naukowe Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego we Wrocławiu (Scientific works of the University of Economics in Wrocław), 526, 214–222.

46. WWF. (2019). EU overshoot day. Living beyond nature’s limits. Retrieved from https://www.footprintnetwork.org/content/uploads/2019/05/WWF_GFN_EU_Oversho ot_Day_report.pdf (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

47. Wyrębska, W. (2014). Freeganizm w Polsce — ekologia i nowy styl życia (transl. Freeganism in Poland-ecology and a new lifestyle). Retrieved from https://www.ekologia.pl/wywiady/freeganizm-w-polsce-ekologia-i-nowy-stylzycia, 19148.html (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

48. Young, W., Hwang, K., McDonald, S., & Oates, C. (2009). Sustainable consumption: Green consumer behaviour when purchasing products. Sustainable Development, 18(1), 20–31. Retrieved from https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/abs/10.1002/sd.394 (Last accessed on May 13, 2020).

49. Zbuchea, A. (2013). Are customers rewarding responsible businesses? An overview of the theory and research in the field of CSR. Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 1(3), 367–386.

50. Zbuchea, A., & Pînzaru, F. (2017). Tailoring CSR strategy to company size? Management Dynamics in the Knowledge Economy, 5(3), 415–437.

Ireneusz P. Rutkowski — Professor of Economics at the Department of Market Research and Services at the Marketing Institute, Poznań University of Economics and Business. Expert of the National Center for Research and Development, member of the Product Development Management Association, the Polish Scientific Society of Marketing, the Scientific Society of Organization and Management and the Polish Economic Society. Author of 10 books and almost 200 other scientific and popular science publications on product strategy, product management, new product development, marketing strategies, market research methods and application of information systems in commercial enterprises.