- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Internet-based mass communication in multi-level marketing companies operating in Poland

Beata Nowotarska-Romaniak1, Sonia Szczepanik2

1,2 Katowice University of Economics, 1 Maja 50, 40-287 Katowice, Poland

1 E-mail: beata.nowotarska-romaniak@uekat.pl

ORCID: 0000-0003-3563-2596

2 E-mail: sonia.szczepanik@edu.uekat.pl

ORCID: 0000-0002-4275-3700

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0020

Abstract:

This study examines the areas of Internet-based mass communication (websites, social media) utilized by multi-level marketing (MLM) companies operating in Poland, using methods including literature review, descriptive analysis, and statistical analysis of primary data. Findings reveal that the most popular MLM websites in Poland are those of foreign-owned companies with over 16 years of operation, which attract more smartphone users, especially among younger firms with high mobile engagement. Average visit duration is around 4 minutes, with longer visits on established global sites, while about half of all visits result in a bounce. Most of the MLM websites examined have content in Polish, primarily featuring product information, company details, and contact information, alongside product and partnership options and required privacy policies. Social media presence is less significant, with Facebook being the most utilized platform, particularly by older firms; Polish-language profiles are rare on more time-intensive platforms like YouTube. Facebook holds the highest average user count, especially for firms operating for over 21 years. This study lays a foundation that may support the first formal classification of MLM enterprises in Poland and inform governmental policies on MLM regulation and PKD code identification. Despite the study’s limitations, the findings contribute a preliminary understanding of MLM companies’ online communication strategies in Poland, paving the way for future qualitative and quantitative research.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 54, Issue 4

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0020

P. 25-48

Published December 16, 2024

Internet-based mass communication in multi-level marketing companies operating in Poland

1. Introduction

Communication – the process of developing and transmitting ideas, information, viewpoints, facts, and sentiments from one location, person, or group to another – is essential to the lives and survival of both individuals and organizations. In today’s hyper-connected societies, efficient communication is more crucial than ever. By the beginning of the fourth quarter of 2023, global Internet usage reached 5.30 billion individuals, representing 65.7% of the world’s total population (Datareportal, 2023).

Phenomena such as globalization, digitalization, and convergence are continually reshaping the way we communicate today. The globalization of business operations, including marketing, incorporates new cultures and new societies, including those outside the circle of Western civilization, into marketing practices. Digitization has shifted much of the burden of communication towards the Internet and especially onto social media platforms. Convergence, meanwhile, is undoubtedly bringing numerous changes to how people experience and interact with media, with brands, and with one other (Giza, 2017, pp. 95–96).

Marketing communication is evolving in accordance with changes brought by its recipients. The global expansion of Internet connectivity has also resulted in an upsurge in social networking, free from the constraints of geographical boundaries or signal failure, allowing for faster and more cost-effective information exchange all over the world, thereby promoting globalization. Even multi-level marketing (MLM) companies, which highly prioritize interpersonal connections, now find it difficult to exist without a digital footprint. Additionally, the capabilities offered by social media bring people together to such a degree that they provide never-before-seen possibilities for recruiting new sellers online.

The online presence of multi-level marketing enterprises has attracted scholarly attention only within certain narrow scopes. Foundational work by Emek et al. (2011) explored the reward mechanisms in multi-level marketing within social networks, while Legara et al. (2008) analyzed the earning potential of multi-level marketing enterprises with the use of mobile communication and the Internet. Bradley and Oates (2021) addressed the post-pandemic revolution in MLM companies, providing recommendations to curb the pandemic-driven expansion of unlawful MLM activities and suggesting regulatory measures that need to be implemented by social media companies. Nadlifatin et al. (2022) explored the behavioral aspects of the millennial generation’s job pursuit in MLM companies given the new role of social media recruitment.

MLM companies’ websites remain understudied, with MLM company transformations seldom being linked to Internet use (Ciongradi, 2017; Chudleigh, 2019). Ciongradi (2017, p. 14) observed that, even at MLM’s inception, consumers could quickly obtain information over the Internet, while Chudleigh (2019, p. 7) noted that women often prefer engaging in MLM commerce online. A more comprehensive study by Cengiz (2020) concluded that intermediaries use MLM-owned websites for purposes of communication, product presentations, networking, member registration, and coordination with headquarters. However, case studies of MLM social media activities suffer from a lack of data, much like in the case of webpages, although scholars do recognize the existence of multi-level marketing companies on social media as a fact (Emek et al., 2011, p. 209; Mangiaratti, 2021, p. 237). Wrenn analyzed the relationship between multi-level marketing (MLM) and neoliberalism (2023, p. 1043), but focused mostly on the perspective of the intermediary, ignoring the social media profiles of corporations.

None of these studies have analyzed online mass communication from the perspective of the multi-level marketing enterprise, none have looked at the Polish market, and very few have described the nature of communication taking place in the online space.

Therefore, the objective of this article is to identify the areas of mass communication on the Internet utilized by Polish multi-level marketing companies, including the corporate web pages of those MLM enterprises and the social media profiles belonging to them. To achieve this, the study employs the following methods: literature analysis, descriptive analysis, and statistical analysis of data acquired from primary research conducted by the authors.

2. Literature review

2.1. Mass communication as crucial element of management strategy

The crucial role of marketing communication is widely acknowledged in the contemporary management literature. Over the years, researchers have developed a variety of perspectives and interpretations of marketing communications within organizations. In the Polish marketing literature, the term “communication” is frequently used as a synonym for “promotion” (Michalski, 2017, p. 341; Czarnecki, 2011, p. 266; Wiktor, 2000, p. 286; Altkorn & Kramer, 1998, p. 117; Pilarczyk, 1996, p. 219; Żurawik & Żurawik, 1996, p. 318). Very few authors distinguish between these two terms, separating them into different categories (Kotler & Keller, 2017, p. 556; Kotler, 2004, p. 66; Woźniak, 2004 p. 151). Those who make such a distinction do so to highlight differences in scope between the two concepts. “Promotion” (Latin promevere, promotio) (Sztucki, 1998, p. 256) implies supporting, favoring, promoting, and stimulating, and so it refers to an activity that conveys a message to the market, using the “marketing tube” to influence the market and drive sales (Pabian, 2020, p. 133; Wiktor, 2001, p. 3–14). Promotion, as a component of communication, consists of messages transmitted by a corporation to raise awareness of its specific products and services, develop interest in them, and induce purchases (Kotler, 2004, p. 66).

In a broader sense, the influence of promotion is enhanced by marketing research and the available market feedback. In this context, promotion can be identified with the communication process, where market dialog fosters interactions between the parties (Pabian 2020, p. 134). “Communication” itself is a more general concept; it transpires regardless of intention; therefore, it is the responsibility of an organization to ensure that its employees, facilities, and activities consistently project a particular set of perceptions concerning the company brand and its commitments to recipients (Kotler, 2004, p. 66).

Today, in an era when the term “integration” is used to describe a wide range of marketing and communication-related activities, where corporate marketing is emerging as the next significant development within the subject (Balmer & Gray, 2003), and where interaction is the preferred mode of communication and relationship marketing is the preferred paradigm (Gronroos, 2004), “marketing communications” now encompasses a broader remit, one that extends beyond product information (Fill & Jamieson, 2011, p. 16). Fill and Turnbull (2016, p. 3) follow this trend and define marketing communications rather broadly, as being concerned with the methods, processes, meanings, perceptions, and actions that audiences (consumers and organizations) undertake about the presentation, consideration, and actions associated with products, services, and brands.

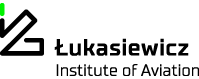

Kotler and Keller (2017, p. 510) perceive marketing communications similarly, in terms of the various ways in which companies attempt to inform, persuade, and remind consumers – directly or indirectly – about the products and brands they offer. As communication channels become increasingly fragmented and congested, it becomes increasingly demanding to select effective methods of message transmission. One can differentiate between personal and non-personal channels of communication, each of which comprises a number of subchannels (Fig. 1). Kotler and Keller (2017) further explain that personal communication channels allow two or more people to communicate face-to-face or in a communicator-recipient relationship via telephone, traditional mail, or e-mail. The effectiveness of these channels relies on individualized presentation and feedback. Non-personal channels (mass communication) are addressed to more than one person; these include advertising, sales promotion, events and experiences, and public relations (Kotler & Keller, 2017, pp. 521–523).

2.2. Managing multi-level marketing enterprises

Multi-level marketing (MLM) is a common method of selling products directly to consumers through independent sales representatives. In its purest form, MLM is a specific type of a distribution system within the direct selling category.

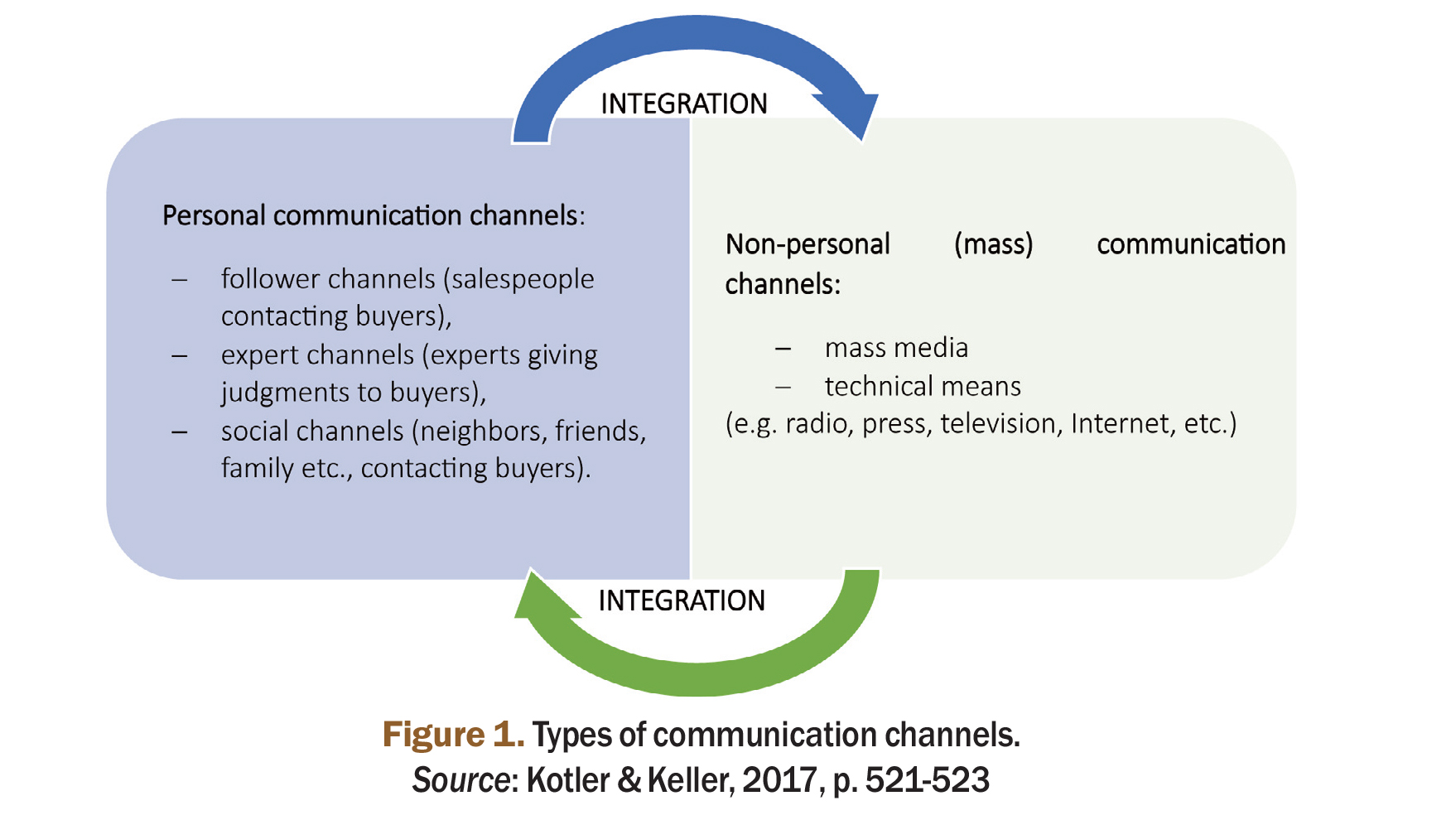

The essence of direct sales involves offering products and services outside regular retail outlets, where building individual relationships with customers is of great importance (Polish Direct Sales Association, 2024). This sales approach allows for direct and flexible contact with a potential buyer (Czubała, 1996, p. 329), which reduces the role of intermediaries in the distribution channel (Jain et al. 2015, p. 904). Direct selling systems can operate as one of two types: single-level and multi-level (Fig. 2).

In single-level marketing, sellers are employed by the company they represent (in Poland, typically under a “contract of agency” or “contract of mandate” – a form of temporary employment) (Orzelska, 2016, p. 72). When concluding transactions with end clients, sellers receive no commission, as their compensation is determined by the terms of their employment contract (Sypniewska, 2013, p. 58). Sales managers, in turn, who are permanently employed by the enterprise and specifically designated for this purpose, are responsible for salesperson recruitment and training (Polish Direct Sales Association, 2024).

Multi-level marketing is characterized by the expansion of the seller’s activity, which in this case serves as an intermediary between the trading company and the end consumer. In this model, intermediaries are not employees of the enterprise but rather operate independently, typically being bound by an independent-contractor arrangement with the enterprise (Koehn 2001 , p. 153; Orzelska, 2016, p. 72). In addition to the function of a seller, intermediaries also recruit new intermediary links (Jain et al., 2015, p. 904). There are two primary sources of income for a multi-level marketing intermediary. The first is the profit margin on their own independent sales of products or services, the second is commissions for the sales achievements of their recruited network (Dewandre & Mahieu, 1996, p. 54). Their earnings determine promotion to higher bonus levels in the MLM structure (Sypniewska, 2013, p. 58).

Effective management of a multi-level marketing distribution system requires a highly complicated communication system. MLM intermediaries create their own network of individual independent units participating in the provision of goods or services for end use or consumption (Stern, El-Ansary, Coughlan, 2002). This network facilitates various flows, including property rights, payments, information, and promotion (Duraj, 2004), as well as after-sales services, complaints, and logistics information (Grabarski et al., 2006). The fundamental principle of MLM is building continuous interactions – relationships that add value over time. Each relationship is different from the previous ones and unique from the perspective of its participants. Effective MLM structures rely on dialogue and two-way communication (Vogelgesang, 2016, p. 134).

Communication with clients and possible intermediaries in MLM enterprises is usually associated with face-to-face contact with buyers, with sales occurring in three main ways: door-to-door, referral sales, and meetings (Waszczyk & Radacki, 2005, pp. 3–4). The sales process is typically also heavily dependent on impersonal conversation and starts with a presentation, proceeds through negotiation and transaction, and ends with an offer to become a seller (Waszczyk & Radacki, 2005, p. 5). Within the MLM structure, there is also a strong emphasis on reciprocal motivation, training, and support among the network of intermediaries, which fosters a shared culture and set of values that heightens the importance of interpersonal contact.

Note that multi-level marketing is a general term describing enterprises that rely on an external network of self-managing intermediaries to distribute their products. As previously mentioned, an MLM network’s intermediaries are not employees but operate independently based on instructions included in individual commercial contracts (Orzelska, 2016, p. 72) negotiated between the entrepreneur and each of the intermediaries separately. Furthermore, enterprises implementing MLM networks can operate across various industries and under diverse legal frameworks. The Polish judicial system, for instance, does not officially classify or regulate companies that incorporate MLM systems into their distribution systems.

The only organization classifying enterprises operating on the basis of multi-level marketing is Network magazine, a private publication focusing on the direct sales and network marketing industry. The magazine’s list classifies companies into four categories: direct selling and MLM companies operating in Poland, companies on a waiting list, anti-companies, and non-operating companies, with active companies being further classified by product type. Unfortunately, the publication does not indicate a timeframe for the list or the date of its last update.

Therefore, this study aims to identify and analyze currently operating MLM companies in Poland, focusing on growth in company registrations, their legal forms, and the main economic activities recognized within traditional regulatory frameworks.

2.3. Online mass communication tools crucial from MLM’s perspective

Modern communication channels are evolving globally, resulting in the emergence of a new hypermedia environment for marketing activities that often necessitates changes in marketing approaches (Kowalska, 2023, p. 82). This shift compels businesses to seek innovative methods of mass marketing communication.

The existing literature provides various classifications of online mass communication tools. IAB Polska (2021) categorizes online marketing communication tools into display, online video, programmatic, SEM, mobile, social media, games and e-sports, e-mail marketing, content marketing, online PR, and influencer marketing. Wiktor (2013, p. 264) previously proposed a classification based on the structure of communication – thus identifying company websites, displays, search websites, e-mail, social networking sites, and finally blogs, chats, and discussion groups – whereas Wiktor (2018, p. 94) later proposed a classification based on virtual communication architecture tools, which he grouped as follows:

- tools for communicating the identity of the message sender (enterprise homepages, company blogs, and others),

- tools for shaping relationships and the image of the company (social networking sites, blogs, chats and discussion groups, e-mail, mailings, social media, newsletters, etc.).

- virtual advertising (promotion) tools (display, search engine advertising, contextual advertising, native advertising, and others).

Managing highly relationship-dependent networks of intermediaries in the MLM distribution system can be quite time-consuming. Online mass communication not only the offers architectural tools to manage such a large group in a virtual environment, but also allows them to be equipped with tools to guide their own sellers’ networks and contact their clients with ease. Given these considerations, the two most crucial virtual communication tools for managing intermediate networks from a business perspective are tolls for communicating identity as the sender of a message and tools for shaping relationships and the image of the company.

2.3.1. The significance of websites

A company website one of the easiest and cheapest ways to build a professional image, attract customers’ attention and initiate a relationship with them (Jellinek, 2017, p. 22). Defined as a dynamically hosted network with a potentially global reach, a “website” (a term originally derived from the “World Wide Web”) encompasses the associated hardware and software necessary to ensure access to it, enabling businesses and consumers to provide hypermedia content, facilitate interactive access, and communicate through the medium (Unold, 2009, p. 151).

Company websites serve as the cornerstone of marketing communication on the Internet, through which most online promotional activities are carried out (Kowalska, 2023, p. 154). In today’s environment, having a website is becoming a standard component of corporate operations. It is frequently the first spot to verify, a company’s “virtual headquarters.” If the website is neglected, the likelihood of a potential relationship being terminated at the initial stage of interaction increases. A well-maintained website, on the other hand, can contribute to numerous marketing and management goals, such as (Mazurek, 2008, p. 41):

- shaping the image and brand of the organisation as modern and innovative,

- informing and disseminating information about the company, products, people, and ideas,

- acquiring new customers and establishing contacts,

- building relationships, entering into dialogue, and interacting,

- integrating users and preparing a platform for information exchange.

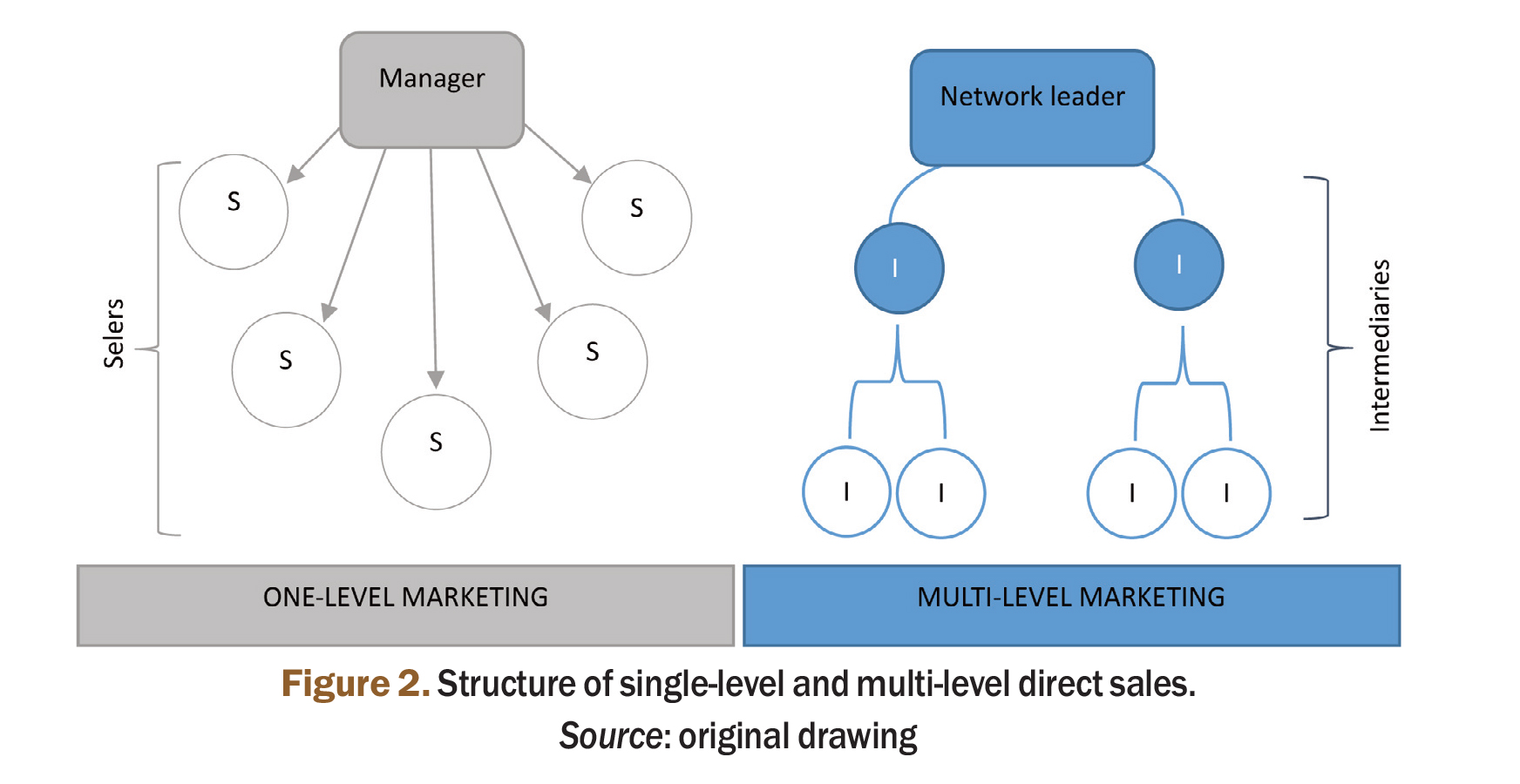

However, achieving these goals requires a website that is engaging, visually appealing, and regularly updated. One of the most important challenges for website creators is to design a site that is attractive in form and interesting enough to encourage Internet users to visit it again (Kowalska, 2023, p. 155). Enterprises that seek to conduct efficient mass communication should adhere to the 7Cs of an effective website, which are a set of fundamental aspects that determine the website’s appeal (Table 1).

One critical feature that is of great importance for the way a website is perceived by the customer, and very often for the image of the company itself, is web usability, i.e. the usefulness of the website. According to the ISO 9241 standard, usability is a measure of the efficiency, effectiveness and satisfaction with which a product can be used by specific users to achieve specific goals in a specific context of use. Jakob Nielsen, a leading expert on usability, regards it as a quality metric linked to operation. He identified five factors influencing the quality of website use (Ideoforce, 2016):

- learnability – the level of difficulty of the activities performed, which translates into how quickly the user can learn how to use the website,

- efficiency – the time needed to perform an activity and the related efficiency of the user using the website,

- memorability – the speed of acquiring skills in navigating the website and the ease of remembering the rules of its use,

- satisfaction – the level of satisfaction users feel when using the website, i.e. users’ overall attitude towards it,

- errors – the number of errors encountered while using the website, allowing us to evaluate its reliability.

In most cases, websites are characterised by a lack of intrusiveness: recipients must find their way to the website themselves and engage with its content. Therefore, for a company’s website to have the intended marketing effect, it must be attractive enough to encourage people to search for it. The basic elements used by companies to improve the quality and attractiveness of a website, and thus the effectiveness of building relationships with Internet users, include featuring interesting content (articles, advice, etc.), newsletters, news sections, Q&A sections; and an e-shop (Härter, 2009, p. 50).

In recent years, there has been limited research on the online presence of multi-level marketing companies. Existing studies tend to discuss MLM’s use of the web only in a general sense, focusing on the changing landscape facing MLM enterprises. For example, Ciongradi (2017, p. 14) notes that with the rise of the Internet, people have easy access to information, which has supported the longevity of some of the earliest MLM companies. Chudleigh (2019, p. 7) points out that women often feel more comfortable doing business with men online than in person, which has likely contributed to the significant involvement of women in MLM. Women may perceive online business interactions as more socially acceptable than discussing MLM opportunities face-to-face, which contributes to the significant involvement of women in MLMs. Women also tend to view conducting business online as more socially acceptable than discussing it in person.

A notable study was conducted in Turkey by Akdemir Cengiz in 2020, focusing on BioBellinda, a multi-level marketing organisation. The study examined how BioBellinda employees use the Internet in their work, revealing that websites are used for several purposes, including communication among intermediaries, product presentation, network-building, member registration, and communication with headquarters (Cengiz, 2020, pp. 61–62, 64).

The literature lacks sufficient information regarding the precise number of currently active websites for multi-level companies, making it impossible to determine the most common aspects of websites dedicated to these organisations, identify those that are most prevalent, and assess their suitability for Polish-speaking audiences. From a mass communication management perspective, understanding how long users stay on an MLM website is essential, as it serves as a tool for both intermediaries and buyers. It is also important to determine which devices are predominantly used to access websites, such as computers or smartphones, to optimize the user experience across platforms.

2.3.2. The significance of websites

The rise of the Internet and social media has reshaped the perception and usage of mass media, leading to a division into old (traditional) and new media. The first group currently includes platforms like radio, television, and the press, while new media includes digital technologies (Kaznowski, 2010). At its core, social media can be defined in various ways, but Ahlqvist et al. (2008) propose an accurate structure that, in their opinion, captures the three most important pillars: Web 2.0, content, and virtual (network) communities (Fig. 3). They refer to this combination as the social media triangle, where each of these three elements is equally crucial to the communication process.

Importantly, social media cannot be equated with mass media (Kaznowski, 2010). Unlike mass media, which is restricted to broad-scale communication, social media offers flexibility in communication formats, allowing for one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many interactions (Cohen, 2020). Although social media can still be viewed as a mass communication medium, it simply offers greater functionality that allows for social interactions.

For multi-level marketing (MLM) companies, platforms like Facebook, Instagram, and YouTube offer substantial opportunities for managing mass communication, enabling interaction not only between the company and users but also among users themselves.

Facebook, part of Meta Platforms, Inc., is the largest social networking site with over 2.91 billion active users (Statista, 2022) and is the most popular social media site in Poland. According to Statcounter research, 77% of social media traffic takes place on the Facebook platform (Statcounter, 2023). The primary tool used by enterprises on Facebook is the “fan page,” a hub bringing together users associated with the company and its fans. It allows companies to provide basic information about themselves (e.g., location, contact information, website address), as well as to publish posts (photos, videos, and links to the online store). Facebook also facilitates direct engagement between customers and company representatives through private messages and comments, fostering community-building and bridging the gap between the company and its audience.

Instagram is a portal also owned by Meta Platforms, Inc., has a community of over 2 billion users (Ahlgreni 2022), with more than 70% of its user base under 35 years old, making it essential for brands targeting younger audiences. The platform focuses on sharing photos and short videos, allowing users to comment, tag, and share posts. Recently, Instagram introduced features like in-app stores and Instastories, which have made it more appealing to businesses looking to promote products and engage users in creative ways.

YouTube is another powerful platform, used by over 2 billion users (Dean, 2021). According to Semrush research from 2020, Polish users spend an average of nearly 32 minutes on YouTube per visit (Skibińska, 2022). Its primary function is video sharing, with users creating channels and posting unlimited content. YouTube allows users to rate videos and post comments under them, providing a valuable platform for storytelling and brand building.

Despite the widespread use of social media by MLM companies, research on this topic remains limited. Most studies acknowledge the presence of MLMs on social media but do not classify or examine this space in depth. Some authors mention it as an established fact in their literature reviews (Emek et al., 2011, p. 209) or case studies (Mangiaratti, 2021, p. 237), while others, like Wrenn, explore MLM as an interactively reinforcing institution of neoliberalism, the ideological operant of this current phase of capitalism (Wrenn, 2023, p. 1043). In this model, intermediaries are expected to use their personal social media to promote products and recruit distributors, with social media becoming a platform for sharing curated posts about the benefits of MLM – such as financial independence and lifestyle improvements – effectively blurring the line between personal and professional life.

The current literature suggests a need for more focused research on MLM intermediaries’ behaviour on social media, as well as corporate profiles, which have received little attention to date. Key areas for further study include identifying the most popular MLM profiles, assessing their customization for Polish audiences, and determining the subscriber base. Such research would provide insights into the platforms most commonly used by MLM enterprises and the engagement strategies that resonate with their audiences.

3. Research methodology

This study involved a quantitative analysis of the content on websites and social media profiles of companies operating in the multi-level marketing (MLM) model.

Given the lack of existing data on the study population, the research was conducted in two stages. Stage one involved updating the list of MLM entities currently operating in Poland, including details such as company names, legal form, Polish Classification of Business Activities (PKD), registration date, and product range. An initial list of 139 companies was downloaded on 1 October 2023, from the Network magazine’s online resources. Each entity was verified using the REGON (National Register of Businesses) database and the National Court Register (KRS) to remove non-existent or bankrupt companies. This filtering process resulted in a final sample of 113 enterprises.

The second stage of the study, the main stage, focused on the online activity of multiple-level marketing enterprises, including websites and social media. In this stage, Internet tools such as Similarweb, Ins.Track.app, and BuzzSumo were used to gather statistics, analytics, rankings, popularity, and other website data. The raw data was then collected and processed using Excel.

The research was conducted over the period from October 2023 to November 2023, using the Internet and social media websites.

4. Results

4.1. Characteristics of the study group

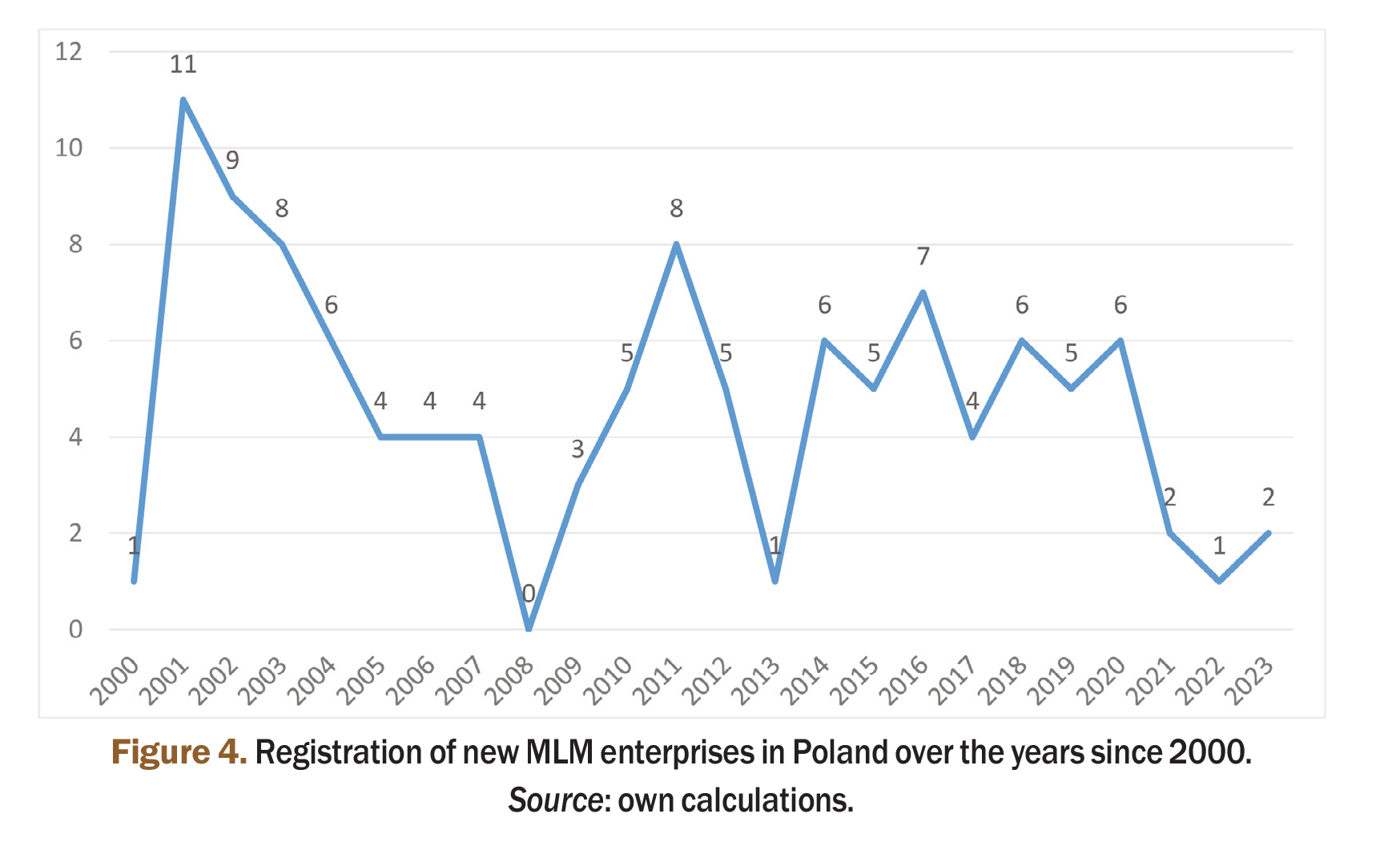

The number of registrations of new multi-level marking enterprises that still exist online today peaked visibly in 2001 and then progressively decreased to zero during the Global Financial Crisis. Since then, the rate of new registrations has shown fluctuations, gradually stabilizing by 2023 (Fig. 4).

When classifying these companies into five-year age ranges, a extraordinary homogeneity emerges. Companies operating for five years or less comprise 19.4% of the group. The next older group, in operation for 6–10 years, accounts for 20.35%. Those with 11–15 years of experience represent 18.58%, while companies in operation for 16–20 years make up 23.01%. The group of companies operating the longest, over 21 years, constitutes 18.58% of the sample.

There are several forms of business activity in Poland, differing in terms of both formal and financial matters – such as place of registration, capital requirements, and methods of representation. Among multi-level marketing companies, the most common legal form is the limited liability company (spółka z ograniczoną odpowiedzialnością), making up 74.34% of the sample. Other legal forms have a smaller shares: self-employment (osoba prowadząca działalność gospodarczą) at 10.62%, joint-stock companies (spółka akcyjna) at 9.73%, limited partnerships (spółka komandytowa) at 4.42% and civil partnerships (spółka cywilna) at 0.88%.

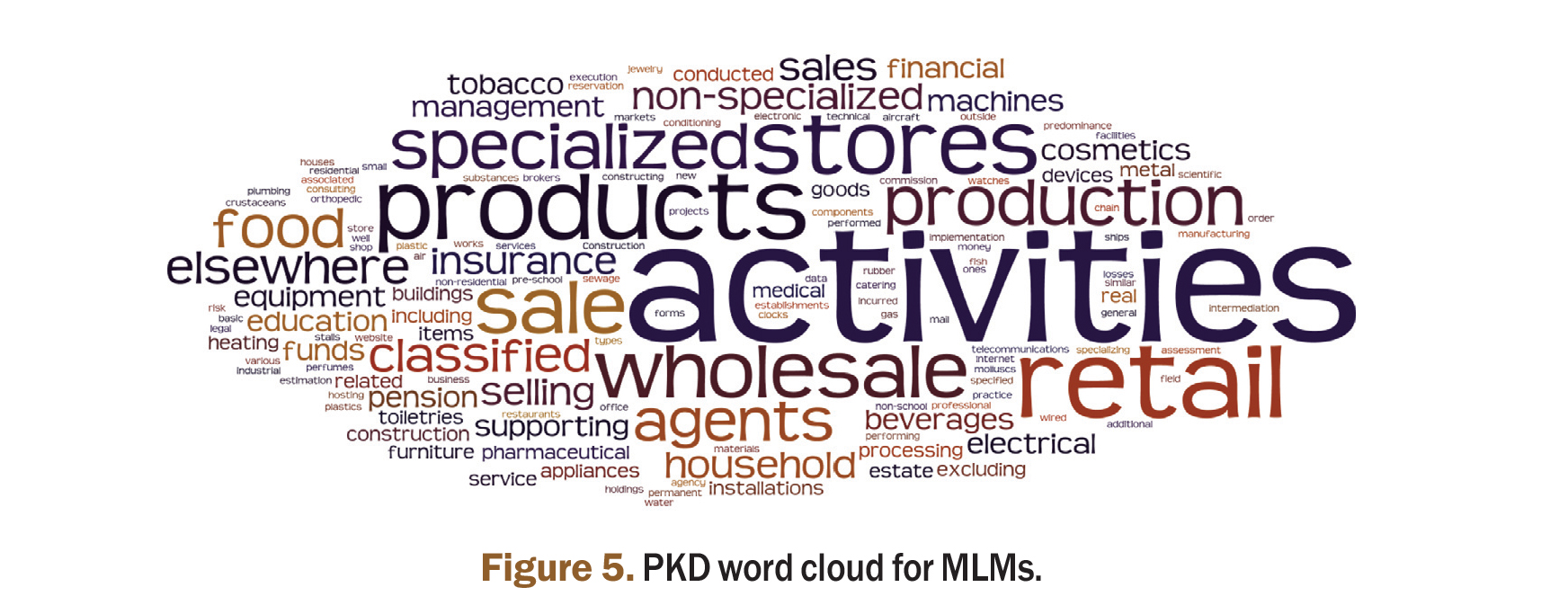

The primary economic activities of these enterprises, as defined by the Polish Classification of Activities (PKD), are organized by the central statistical office Statistics Poland (GUS). Each company has at least one active PKD code that reflects its main activity. To visualize the key economic activities, a word cloud was created from keywords using the Wordle application (Fig. 5). The most common terms included “activities,” “products,” “specialised,” “stores,” and “retail.”

Ownership structure is another critical classification. In the private sector, ownership may be national, foreign, and mixed. The majority of companies in our sample are domestically owned (63.46%) and one-third are foreign owned (36.54%), with only 8.65% being mixed.

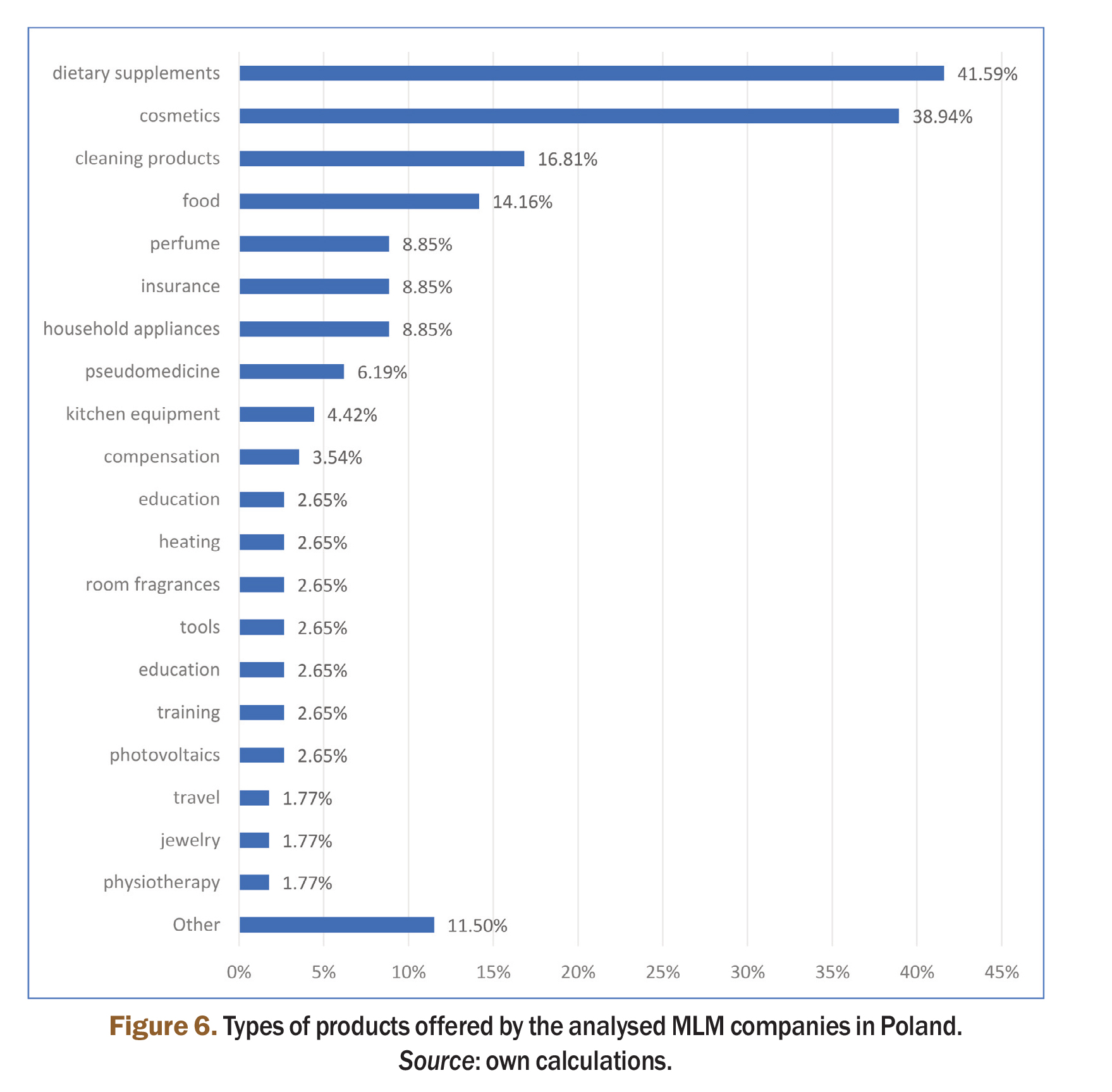

MLM companies in Poland offer a diverse range of products. One of the most frequently used product categories is “wellness items,” but due to the vague and expansive nature of this term, it was rejected in favour of more precise product categories taken from the literature (Fig. 6). Dietary supplements (41.59%) and cosmetics (38.94%) are by far the most numerous groups of products sold. Less popular but still relevant are cleaning supplies (16.81%) and food (14.16%).

4.2. Website analysis

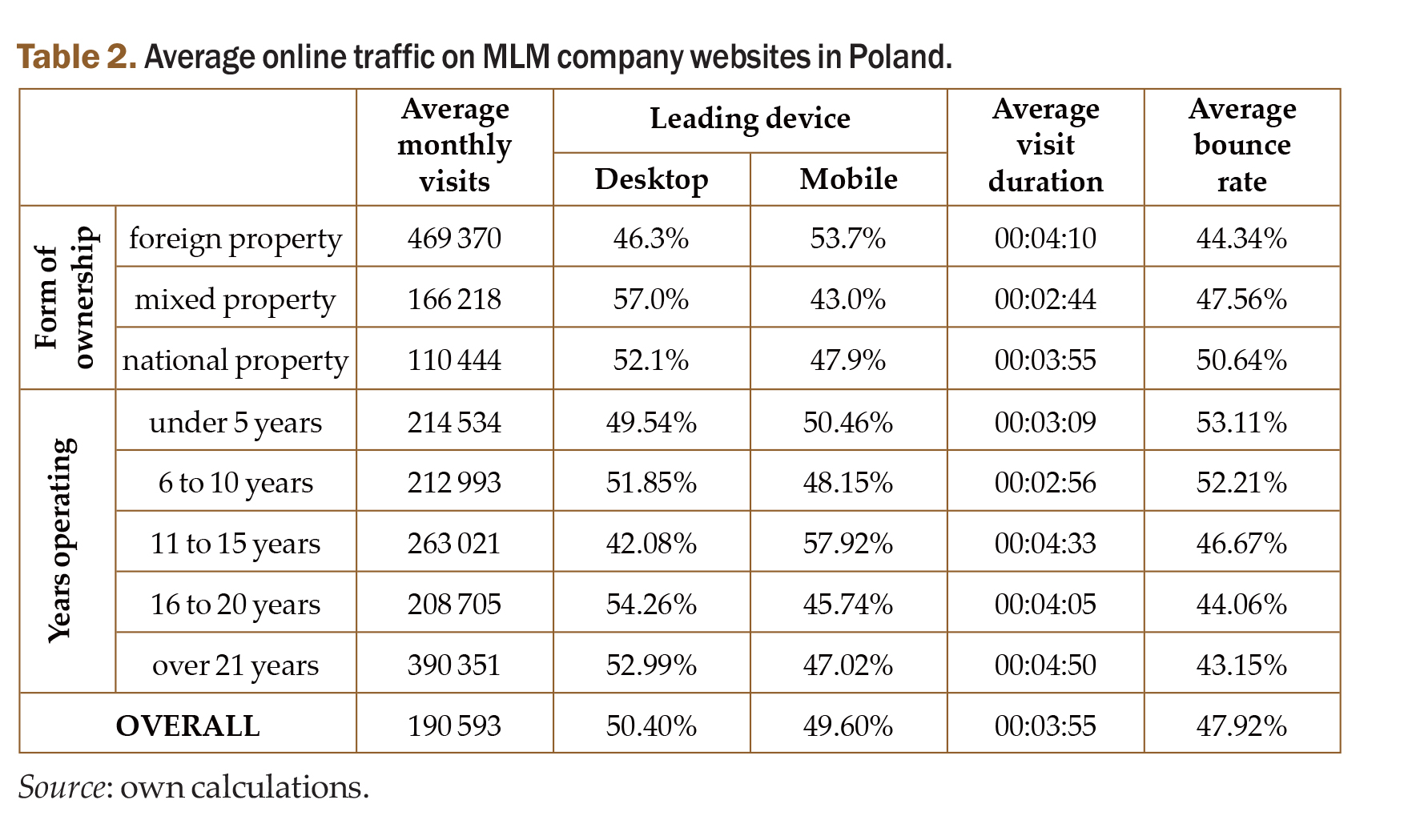

In this next part of the study, the Similarweb search engine was used to analyse the traffic on the websites of MLM companies operating in Poland for three months (from September to October 2023) (Table 2). The total number of businesses having websites was 103.

Average monthly visits across all websites exceeded 190,000. The most popular sites were those owned by foreigners and those that had been in operation for more than 16 years. Device preference among users showed minimal difference, although foreign-owned sites were more frequently accessed via smartphones. Additionally, younger companies attracted mobile users more often than older enterprises. The average visit duration on these websites was almost 4 minutes, with foreign-owned and more experienced companies seeing users spend more time.

The bounce rate – the percentage of users who leave a site after viewing only one page – is a metric used to assess a website’s effectiveness in terms of user engagement. According to HubSpot (2023), a bounce rate of 26% to 70% is typical, with rates of 40% or less considered desirable in general and rates of 55% or higher considered excessive, indicating a need for improvement (TheFullStory, 2023). The average bounce rate for the MLM companies in our sample was 48%. This metric was notably higher in the case of domestically owned businesses and those with a short history of operation. Companies with foreign funding and more work experience, on the other hand, performed considerably better, demonstrating better user retention.

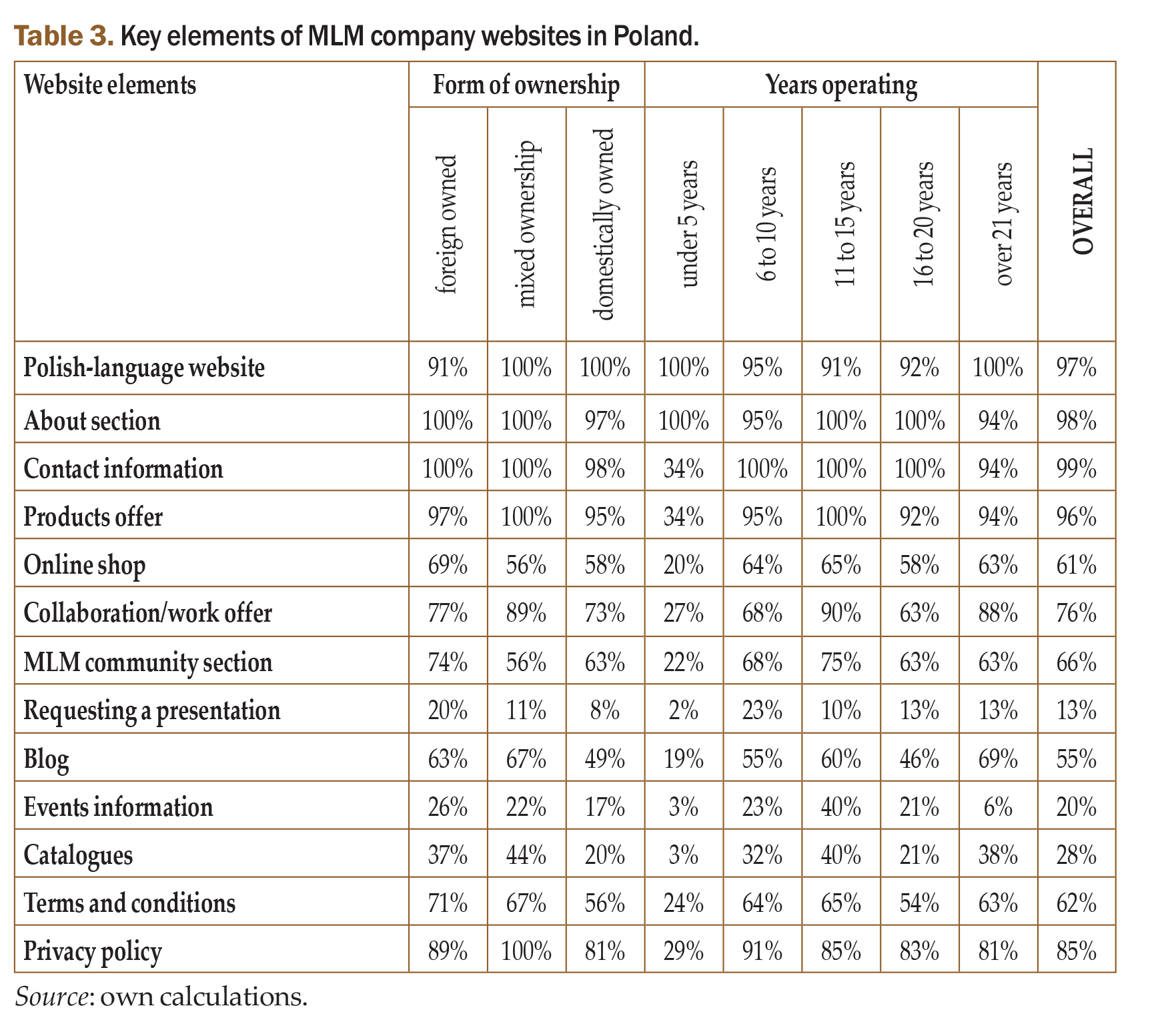

In the next step, all of the available multi-level marketing companies’ websites were examined in terms of key elements, such as website language, company information, contact details or form, product offerings, online shop, collaboration/work offers, intermediary community section, request form for product presentation, events calendar, catalogues, terms and conditions, and privacy policy (Table 3).

The majority of the websites analysed were Polish-owned. The most common elements were the product offer, company details, and contact information. Collaboration opportunities and privacy policies were also frequent. Interestingly, requests for product presentations, once a standard feature, are becoming increasingly rare. Newer websites often lack essential elements such as online shops, blogs, and even terms and conditions, potentially impacting user engagement and trust.

4.3. Social media analysis

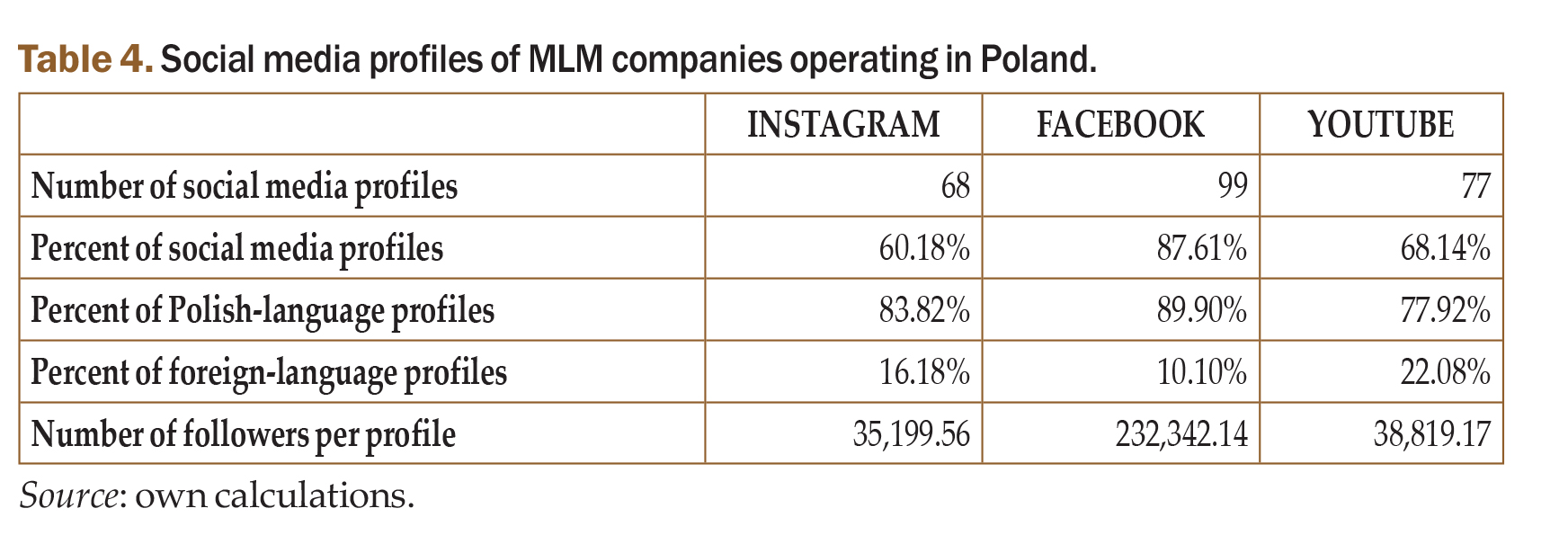

Social media platforms were found to be not as widely used among Polish MLM companies as websites (Table 4). Facebook is the most popular social media page, used by 87.61% of the enterprises studied, with YouTube as the second most popular (68.14%) followed by Instagram with 60.18%.

Not all of the companies that do have social media accounts provide Polish-language profiles. YouTube profiles are the most likely not to be in Polish, with 22.08% of profiles being in a foreign language, followed by Instagram at 16.18% and Facebook at 10.10%. Analysing the average number of subscribers shows that Facebook is the most popular social media site among Polish MLM enterprises, with 232,342.14 followers per profile

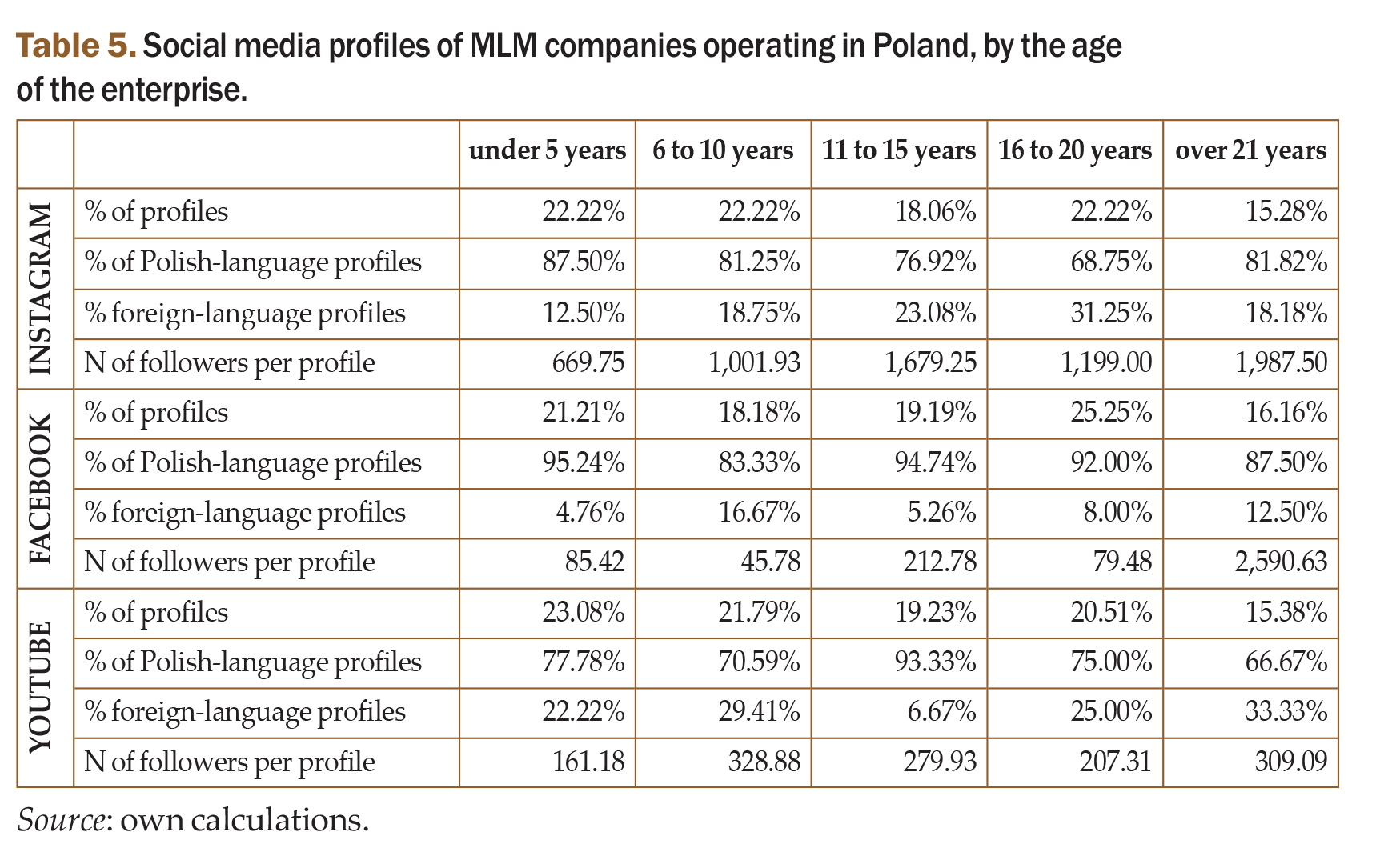

Looking at the MLM social media activity through the lens of company age (Table 5) reveals that the most significant follower numbers on Facebook are enjoyed more by mature companies. However, enterprises younger than 21 years old also rate this particular social media platform as a popular one.

Instagram users are almost equally divided; however, it’s important to notice that older companies struggle to provide profiles adapted to Polish speakers. Facebook profiles are also similarly divided, but here, younger and older companies struggle with Polish accommodation equally. On the other hand, YouTube is the domain of younger generations, hence the content posted can usually be foreign-language.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to identify areas of mass communication on the Internet utilized by multi-level marketing (MLM) companies in Poland. The findings suggests that MLM companies in Poland are indeed active in developing their brands on the Internet using both social media sites and websites.

Achieving this goal required an in-depth analysis of a carefully selected research sample, along with a comprehensive characterization of the currently operating market of MLM in Poland based on the materials of Network magazine. As such, this study represents the first market characterization of this type in the MLM literature.

The number of companies found to be active in the analysed period totalled 113, representing various stages of development, but most often they are limited liability companies. Their primary economic activities, as indicated by their PKD codes, were found to be focused around the terms “activities,” “products,” “specialized,” “stores,” and “retail.” Most often, they sell dietary supplements, cosmetics, cleaning products and food.

Foreign-owned and well-established companies (over 16 years in operation) had the most popular websites. Device preferences were minimal, though foreign-owned sites showed higher smartphone usage. Younger companies also tend to attract mobile users more frequently. The average visit duration across MLM websites was about 4 minutes, with users spending more time on sites of international and experienced companies. The average bounce rate was 48%, with higher rates for domestically owned and younger companies, while foreign-funded and established enterprises demonstrated better retention. The majority of websites were in Polish, with product offerings, company information, and contact details as the most common content elements. Partnership and product offers were also frequently displayed, along with the mandated privacy policies and terms and conditions.

Websites are more popular than social media platforms. Facebook is the most popular social media platform for multi-level marketing. Not all social media companies provide Polish-language profiles, especially on those social media sites that typically provide longer types of content, such as YouTube. By average number of subscribers, Facebook is the most popular social networking site, but this number comes from the older generation of enterprises that have operating for over 21 years.

These findings are generally consistent with the limited previously existing research, particularly regarding the use of websites for intermediary communication (Cengiz, 2020). MLM enterprises operating in Poland and their intermediaries have an established online presence, creating a network of connections between companies, intermediaries, and customers. Social media platforms foster communities of fans and supporters around these businesses.

This study has at least several potential limitations. The absence of prior research on MLM’s online presence introduces challenges in identifying reliable trends or relationships within the data. The initial list of MLM enterprises was sourced from a privately-owned magazine, which may affect the reliability of the sample. Furthermore, the lack of comprehensive data and comparative studies on MLM’s online presence limits the ability to cross-check results with other research. The study’s short duration did not allow for a broader analysis over time, and the reliance on third-party analysis tools may not fully capture the diversity and complexity of the MLM population.

Nevertheless, this study lays a basic foundation for future research on the mass communication strategies of MLM enterprises online. Future studies would benefit from a more robust classification of MLM enterprises, supported by a wider range of online tools such as AI and specialized search engines. Methodologically, incorporating qualitative research approaches could deepen understanding, particularly in social media communication, where netnography methods would provide valuable insights.

Despite its limitations, this study suggests several implications. The findings could support the development of the first official classification for MLM enterprises and encourage governments to create regulatory frameworks that better identify MLM companies within PKD codes. Ultimately, this study represents a first step in understanding how MLM companies communicate via online mass media, laying a foundation for further qualitative and quantitative research. It opens up opportunities for exploring social media engagement, studying content through qualitative methods, and interacting with online users.

References

Ahlqvist, T., Bäck, A., Halonen, M., & Heinonen, S. (2008). Social media roadmaps: exploring the futures triggered by social media. VTT Tiedotteita-Valtion Teknillinen Tutkimuskeskus Research Notes 2454.

Altkorn, J., & Kramer, T. (1998). Leksykon marketingu [Lexicon of Marketing]. PWE, Warszawa.

Bradley, C., & Oates, H. E. (2021). The multi-level marketing pandemic. Tennessee Law Review, 89, 321.

Cengiz, H. A. (2020). The perception of multi-level marketing by its members in Turkey. Academic Review of Consumer Behavior and Research, 1(1), 50–71.

Chudleigh, H. E. (2019). The new face of business: Comparing male and female gender stereotypes in multi-level marketing Facebook posts in India (Master’s thesis, Brigham Young University).

Ciongradi, I. M. (2017). Multilevel marketing for everybody is not forever. Bulletin of the Transilvania University of Brasov. Series V: Economic Sciences, 10(2), 11–16.

Cohen, H. (2020). Social media definition: The guide you need to get results. Retrieved from https://heidicohen.com/social-media-definition/

Czarnecki, A. (2011). Narzędzia komunikacji marketingowej [Marketing Communication Tools]. In L. Grabarski (Ed.), Marketing. Koncepcja skutecznych działań [Marketing: The Concept of Effective Actions] (pp. 195–231). PWE.

Czubała, A. (2000). Dystrybucja [Distribution]. In J. Altkorn (Ed.), Podstawy marketingu [Basics of Marketing] (pp. 285–345). Instytut Marketingu.

Czubała, A. (2001). Distribution of products. Polish Economic Publishing House.

Balmer, J. M., & Gray, E. R. (2003). Corporate brands: What are they? What of them? European Journal of Marketing, 37(7/8), 972–997.

Datareportal. (2023). Digital around the world. Retrieved from https://datareportal.com/global-digital-overview

Dean, B. (2021). How many people use YouTube in 2022? Retrieved from https://backlinko.com/youtube-users

Dewandre, P., & Mahieu, C. (1996). Przyszłość marketingu wielopoziomowego w Europie. Racje sukcesu MWP [The Future of Multi-level Marketing in Europe. Reasons for MLM Success]. Horizon International, Szczecin.

Duraj, J. (2004). Podstawy ekonomiki przedsiębiorstwa [Basics of Enterprise Economics]. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, Warszawa.

Emek, Y., Karidi, R., Tennenholtz, M., & Zohar, A. (2011, June). Mechanisms for multi-level marketing. In Proceedings of the 12th ACM conference on Electronic commerce (pp. 209–218).

Fill, C., & Jamieson, B. (2023). Marketing Communications. Edinburgh Business School Heriot-Watt University, Edinburgh, United Kingdom.

Fill, C., & Turnbull, S. (2016). Marketing communications: Discovery, creation and conversations. Pearson.

Giza, A. (2017). Uczeń czarnoksiężnika, czyli społeczna historia marketingu [The Sorcerer’s Apprentice: A Social History of Marketing]. Wydawnictwa Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

Grabarski, L., Rutkowski, I., & Wrzosek, W. (2006). Marketing. Punkt zwrotny nowoczesnej firmy [Marketing: A Turning Point for the Modern Company]. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, Warszawa.

Gronroos, C. (2004). The relationship marketing process: Communication, interaction, dialogue, value. Journal of Business and Industrial Marketing, 19(2), 99–113.

Härter, G. (2009). Jak zdobyć klientów w internecie [How to Gain Clients Online]. Wydawnictwo BC.

HubSpot. (2023). What is bounce rate and how to fix it. Retrieved from: https://blog.hubspot.com/marketing/what-is-bounce-rate-fix

IAB Polska. (2020/2021). Raport strategiczny. Internet 2020/2021 [Strategic Report: Internet 2020/2021]. Retrieved from https://www.iab.org.pl/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Raport-Strategiczny-2021.pdf

Ideoforce. (2016). Web usability – czym jest użyteczność stron internetowych [Web Usability – What is it]. Retrieved from https://www.ideoforce.pl/akademia/web-usability-czyli-na-czym-polega-uzytecznosc-stron-internetowych,78.html

Jain, S., Singla, B., & Shashi, S. (2015). Motivational factors in multilevel marketing business: A confirmatory approach. Management Science Letters, 5(10), 903–914.

Jellinek, R. (2017). Trzy filary biznesu w internecie. Kompleksowy przewodnik po narzędziach e-marketingowych [The Three Pillars of Online Business: A Comprehensive Guide to E-Marketing Tools]. Agencja interaktywna.

Kaznowski, D. (2010). Definicja social media [Definition of Social Media]. Retrieved from https://networkeddigital.wordpress.com/2010/04/17/definicja-social-media/

Koehn, D. (2001). Ethical issues connected with multi-level marketing schemes. Journal of Business Ethics, 29(12), 153–160.

Kotler, Ph. (2004). Marketing od A do Z [Marketing from A to Z]. PWE.

Kotler, Ph., & Keller, K. L. (2017). Marketing. Dom Wydawniczy Rebis, Poznań.

Kowalska, M. (2023). Marketing relacji w dobie technologii cyfrowych [Relationship Marketing in the Digital Age]. PWE.

Legara, E. F., Monterola, C., Juanico, D. E., Litong-Palima, M., & Saloma, C. (2008). Earning potential in multilevel marketing enterprises. Physica A: Statistical Mechanics and its Applications, 387(19–20), 4889–4895.

Mangiaratti, C. H. (2021). Big dreams and pyramid schemes: The FTC’s path to improving multi–level marketing consumer protection in light of AMG Capital Management and the 2016 Herbalife settlement. Journal of Law and Policy, 30, 228.

Mazurek, G. (2008). Promocja w Internecie – narzędzia, zarządzanie, praktyka [Internet Promotion – Tools, Management, Practice]. Ośrodek Doradztwa i Doskonalenia Kadr.

Michalski, E. (2017). Marketing: podręcznik akademicki [Marketing: An Academic Textbook]. PWN.

Nadlifatin, R., Persada, S. F., Clarinda, M., Handiwibowo, G. A., Laksitowati, R. R., Prasetyo, Y. T., & Redi, A. A. N. P. (2022). Social media-based online entrepreneurship approach on millennials: A measurement of job pursuit intention on multi-level marketing. Procedia Computer Science, 197, 110–117.

Orzelska, D. (2016). Niestandardowe formy zatrudnienia: wyzwania dla pracowników i pracodawców na przykładzie sektora sprzedaży bezpośredniej [Non-standard Forms of Employment: Challenges for Employees and Employers in the Direct Sales Sector]. Rozwój Regionalny i Lokalny, 70, 70–79.

Pabian, A. (2020). Komunikacja rynkowa przedsiębiorstwa [Market Communication of the Enterprise]. In A. Czubała, R. Niestrój, & A. Pabian (Eds.), Marketing w przedsiębiorstwie – ujęcie operacyjne [Marketing in the Enterprise – An Operational Approach]. PWE.

Pilarczyk, B. (1999). Promocja i reklama [Promotion and Advertising]. In H. Mruk (Ed.), Podstawy marketingu [Basics of Marketing] (pp. 217–246). Akademia Ekonomiczna w Poznaniu.

Polish Direct Sales Association. (2023). Polskie Stowarzyszenie Sprzedaży Bezpośredniej. Retrieved from https://pssb.pl/

Skibińska, A. (2022). Najpopularniejsze media społecznościowe w 2021 roku [Most Popular Social Media in 2021]. Artefakt. Retrieved from https://www.artefakt.pl/blog/epr/najpopularniejsze-media-spolecznosciowe-w-2021-roku Statcounter. (2022). Social media stats Poland. Retrieved from https://gs.statcounter.com/social-media-stats/all/poland/2021

Statista. (2022). Number of monthly active Facebook users worldwide as of 4th quarter 2021. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/264810/number-of-monthly-active-facebook-users-worldwide/

Stern, L. W., El-Ansary, A. I., & Coughlan, A. T. (2002). Kanały marketingowe [Marketing Channels]. Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne, Warszawa.

Sypniewska, B. A. (2013). Marketing wielopoziomowy – szansa czy zagrożenie [Multi-level Marketing – Opportunity or Threat]. Zeszyty Naukowe PWSZ w Płocku. Nauki Ekonomiczne, 17, 54–73.

Sztucki, T. (1999). Promocja: sztuka pozyskiwania nabywców [Promotion: The Art of Acquiring Customers]. Agencja Wydawnicza Placet.

TheFullStory. (2023). What is a good bounce rate? Retrieved from https://www.fullstory.com/blog/what-is-a-good-bounce-rate/

Unold, J. (2001). Systemy informacyjne marketingu [Marketing Information Systems]. Wydawnictwo Akademii Ekonomicznej im. Oskara Langego.

Vogelgegang, A. (2016). Potencjał multilevel marketingu [The Potential of Multi-level Marketing]. WiS Opcjon.

Waszczyk, M., & Radacki, S. (2005). Problemy moralne w sprzedaży bezpośredniej [Moral Issues in Direct Sales]. Pieniądze i Więź, 9, 63–73.

Wiktor, J. W. (2000). Promocja [Promotion]. In J. Altkorn (Ed.), Podstawy marketingu [Basics of Marketing]. Instytut Marketingu.

Wiktor, J. W. (2001). Promocja. System komunikacji przedsiębiorstwa z rynkiem [Promotion: The Enterprise’s Communication System with the Market]. PWN.

Wiktor, J. W. (2013). Komunikacja marketingowa: modele, struktury, formy przekazu [Marketing Communication: Models, Structures, Forms of Message]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Wiktor, J. W. (2018). Architektura systemu komunikacji wirtualnej – uwarunkowania i wyzwania [Architecture of the Virtual Communication System – Conditions and Challenges]. In B. Gregor & D. Kaczorowska-Spychalska (Eds.), Marketing w erze technologii cyfrowych. Nowoczesne koncepcje i wyzwania [Marketing in the Digital Technology Era: Modern Concepts and Challenges]. PWN.

Woźniak, B. (2004). Polityka promocji [Promotion Policy]. In W. Deluga (Ed.), Marketing w zarysie [Marketing in Outline] (pp. 151–172). Wydawnictwo Uczelniane Politechniki Koszalińskiej.

Wrenn, M. V. (2023). Multi-Level Marketing: A Neoliberal Institution. Journal of Economic Issues, 57(4), 1043–1061.

Żurawik, B., & Żurawik, W. (1996). Zarządzanie marketingiem w przedsiębiorstwie [Marketing Management in the Enterprise]. PWE.

Beata Nowotarska-Roamaniak – habilitated doctor, university professor in the Department of Marketing at the University of Economics in Katowice. She has authored and co-authored numerous books in the fields of healthcare, insurance, and marketing services, as well as more than two hundred scientific articles on consumer behavior, service marketing, and promotion, which have been published both domestically and internationally. That are frequently cited by both Polish and foreign authors. Beata Nowotarska-Romaniak is involved in adapting marketing in insurance and healthcare services. She also conducts research on consumer behavior in the insurance and healthcare service markets, delivers lectures and training sessions, among others, for managers and employees of healthcare facilities, banks, and insurance companies. She she collaborated on the project “Managerial Support for Healthcare Facility Management Staff” co-financed by the European Union under the European Social Fund. Students, postgraduate students, and doctoral students alike hold Beata Nowotarska-Romaniak in high regard as an educator. She lectures a variety of subjects and creates his own programs. She teaches seminars at the undergraduate, master’s, and doctoral levels. She serves as a reviewer for an extensive array of articles and monographs.

Sonia Szczepanik – Graduated from Finance and Accounting (BA) as well as Management (MA) at the University of Economics in Katowice. Currently enrolled in a PhD program in Management and quality sciences at the Doctoral School of the University of Economics in Katowice. Author and co-author of scientific articles in the field of crisis management, insurance services, dietary supplements market, direct sales and multi-level marketing, published in Polish and English.