- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Personal brand — instructions of use. Do young professionals want and need to be taught personal branding?

Joanna Macalik*

Katedra Zarządzania Marketingowego, Uniwersytet Ekonomiczny we Wrocławiu, Wydział Zarządzania,

ul. Komandorska 118/120, 53-345 Wrocław, Poland

*E-mail: joanna.macalik@ue.wroc.pl

ORCID: 0000-0003-3946-8834

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0009

Abstract:

In modern business, personal branding (PB) is perceived as a ‘leadership imperative’. The main purpose of the present article is to analyse last-year students, often being professionals and market-entrant entrepreneurs, at the same time, attitudes towards PB’s role in business.

Primarily, it is investigated whether they need to be taught principles, rules and tools of PB in the course of their studies. To achieve this goal, a qualitative, in-depth interview method is used. The data are analysed using the thematic analysis method. The results obtained supplement the knowledge of management sciences with issues concerning the perception of PB and state a significant set of practical implications for the authorities of universities and the authors of academic curricula.

MINIB, 2023, Vol. 48, Issue 2

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2023-0009

P. 41-60

Published June 31, 2023

Personal brand — instructions of use. Do young professionals want and need to be taught personal branding?

Introduction

The modern labour market has become a highly competitive environment, especially for young professionals, who often are either recent graduates or students in the last years of their studies. The energy crisis, the war in Ukraine, the global pandemic and many more minor forces caused significant difficulties both for those looking for a job and those who have decided about self-employment (Eurofound, 2022). In this context, the idea of adapting teaching at universities to the labour market requirements becomes a crucial aspect of the ongoing discussion concerning the didactic process.

Developing and implementing study programs that will meet the needs of both the labour market and young professionals entering this market is a challenge that — according to various studies, surveys and reports — universities are currently unable to meet. Analysis of these types of statistics leads to the pessimistic conclusion that graduates leave the halls of universities without a set of skills aligned with labour market needs in the short and long terms (OECD, 2021) — and in making this observation with regard to paucity of skills, we are including both hard and soft skills.

As it appears, in the constantly changing environment, soft skills, defined as non-technical skills that impact one’s performance in the workplace and support situational awareness and enhance an individual’s ability to get a job done, are even more critical. By equipping graduates with foundational soft skills, such as language proficiency, self-presentation to teamwork and time management, universities can prepare them to respond in an agile manner to megatrends and help them to upskill and reskill throughout their lives and, in turn, to thrive in the modern employment environment.

The authoress of the following paper is particularly interested in the situation of young professionals — self-employed entrepreneurs, those creating their first business ventures, start-ups founders and other similar classes of entrepreneurial persons. Conducting a literature review on the soft skills of entrepreneurs enables us to conclude that one of the key competencies might nowadays be an ability to create their personal brand, which, in turn, will reinforce the venture performance. Some researchers even claim that educating students on PB will be a critical element enabling them to succeed in the labour market (Culo et al., 2022).

For this reason, in the present study, the authoress initially analyses young professionals’ opinion on the PB role in their career and their assessment of previous education received in this area when studying at the university.

Following the introductory portion above, the remainder of the present study has been divided into four parts. In the first part, a brief overview of the previous research on education on PB is presented. The second part concerns the methodology, research questions and sample selection method, while the third presents the main findings of the research. Finally, the last part provides the conclusion, as well as a summary and critique of the findings.

Literature Review

The world of education is constantly changing. Gone are the days when a university degree was indispensable to work in an attractive position or develop one’s own business. In the age of the Internet and universal access to knowledge, higher education is no longer a critical pathway to develop the skills that lead to a good job and a successful career. Universities, particularly those wishing to maintain demand for studies and ‘make a difference’ to society and the economy, should serve students with a mix of knowledge and skills, and these should ideally be of such a nature that they are not only sought-after by employers in their potential employees but also would constitute a necessity for the students themselves when they engage in entrepreneurial activity in the future. Various reports clearly show that soft skills are an increasingly important part of this mix. The most in-demand competencies, called ‘power skills’ (Udemy Business, 2022), refer to leadership, teamwork, communication and productivity. Deloitte Access Economics (2017) forecasts that soft skill-intensive occupations will account for two-thirds of all jobs by 2030, compared to half of all jobs in 2000.

Constantly changing market requires special skills, especially from entrepreneurs. Starting and developing a new business, especially in such a turbulent environment as the third decade of the 21st century, is a challenging long-term process. As Gibb and Ritchie (1982) concluded in their classic work, in the emergent stage, founders must make farreaching decisions very early, in a poorly structured environment and when they may have few resources.

This is why those who represent the so-called ‘entrepreneurial personality’ are generally more likely to succeed. A significant relationship between the entrepreneurial competencies of the leader and firm performance has been reported in empirical studies (Boyatzis, 2006; Chatterjee & Das, 2015; Frank et al., 2007; Yankov et al., 2014; Zaech & Baldegger, 2017). Various studies have confirmed that business success is closely tied to the specific psychological attributes of the founder. These attributes may take the form of personal traits, e.g. need for achievement, locus of control, risk-taking, self-efficacy, tolerance of ambiguity, autonomy, independence, optimism and innovativeness (Chatterjee & Das, 2015), or behaviours such as business leadership, financial discipline, networking, resource management and building relationships with employees and customers (Baluku et al., 2016). While most of these competencies are mainly innate, many can be learned and honed over time not only by practice but also in the course of formal education. The ability of PB is a competency that combines several soft skills — such as self-awareness, written and oral communication skills, social interaction, seeking feedback (Manai & Holmlund, 2015) and of course the ‘underpinning concept of personal branding — selfpresentation’ (Goffman, 1959).

PB is defined as a planned process in which people make efforts to market themselves. According to Khedher (2014), this process involves three phases: (1) establishing a brand identity, which means differentiating themselves and standing out from the crowd while fitting the expectations of a specific target market; (2) developing the brand’s positioning by the organisation of an active communication of one’s brand identity through managing behaviour, communication and symbolism; and (3) evaluating a brand’s image in terms of personal and professional objectives (Khedher, 2014).

The teaching of PB was first mentioned more than 20 years ago by Shepard (2005), who pointed to some of the challenges facing higher education in attempting to create a curricular framework within which marketing professionals can learn how to market and brand themselves effectively. The author also noticed-and this is an observation that still holds good-that the authors of self-help books, career advisors and the Internet, in general, appear to be the primary sources of advice currently available on the subject, as academic programs and scientific research are lagging behind the business world and do not cover or barely cover this area.

Since that time, only a select multitude of researchers have discussed the need to include teaching about PB in academic curricula. Edmiston (2014) suggested that universities should provide students with a framework that leverages online media for PB purposes. In turn, Johnson (2017) advised academics to incorporate assignments into their classes, such as developing a personal brand statement or demonstrating one’s personal brand on social media, to facilitate students’ transition into their careers. Similarly, Wetsch (2012) presented the idea of PB assignment, intended to acquaint students with the possibilities of creating their personal brands through social media usage. Ilies (2018) invented a simple process model that can be used to create a PB plan with students. Stanton & Stanton (2013) developed an idea of an assignment based on creating a personal brand statement combined with students’ own evaluation of the results, which was an initial attempt to assess the effectiveness of the teaching of PB skills. In the case of this research, the students performing the tasks declared, among other observations, that developing a personal brand statement made them feel more confident about applying for internships or jobs (4.62 on a 5-point scale) and that the assignment helped them gain a better understanding of their personal strengths (4.33). It was also confirmed in the course of confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and structural equation modelling (SEM) that students’ personal brand concept belief and personal brand management efficacy positively influenced the personal brand authenticity of their later-created personal brand (Allison et al., 2020).

It is also worth mentioning that some studies in the literature considered university education about specific channels of PB, especially those related to the online environment, such as business and the employment-focussed social media platform LinkedIn (McCorkle & McCorkle, 2012; Zhao, 2021), and its tools, such as storytelling (Jones & Leverenz, 2017).

As noted by Gorbatov et al. (2018), two approaches to the teaching of PB are discernible in the scientific debate. One of them suggests that PB is a means to developing accompanying skills, such as awareness of online communication issues or metacognitive, creative and critical thinking skills (Lorgnier & O’Rourke, 2011), while the second sees PB as a core subject that requires to be studied in its own right, especially in relation to the provision of entrepreneurial, and other business field related, education.

As revealed by the literature review presented above, only in a few research studies were students asked about their assessment of PB teaching at the university level, as well about the extent to which PB skills could be imbibed by them through other avenues of formal education, and seldom were they afforded the opportunity to place on record their needs with regard to acquisition of PB-related skills.

To address the research gap identified above, qualitative research, with the participation of final-year students and recently graduated young professionals declaring themselves as professionals or entrepreneurs, was prepared. The choice of method, selection of respondents and method of data collection and analysis will be presented in the following subsection of the paper.

Methods

Research question

Following above consideration and the research problem identified in the introduction to this article, it was decided to formulate the following research questions:

RQ1: What is the understanding of the personal brand concept among young professionals?

RQ2: Do young professionals (recent college students, young graduates) think PB should be taught at the university? Why yes/no?

Method choice and data collection

In order to gain insight into students’ perception of PB teaching in academia and address the research questions of the study, an individual in-depth interview method was adopted. Using semi-structured interviews, conducted in a conversational and flexible tone, the authoress provided respondents with guiding questions and remained open for their additional comments and thoughts regarding the subject of the study. Participants were asked to share observations about their and their peers’ attitudes towards the topic.

Interviewees were recruited using purposive (non-probabilistic) sampling, a kind of research sample selection that does not aim at being representative or generalisable (Campbell et al., 2020) but instead at being meaningful, permitting in-depth analyses and defining particular characteristics for a purpose relevant to the study.

The respondents to the research were students participating in the Business Individual Study Program (BIPS), a proprietary project of the Wroclaw University of Economics and Business (WUEB) in Wroclaw, Poland. The program is focused on building STUDENTACADEMICBUSINESS relationships and aims to accelerate the student’s personal, social and professional development by paying more attention to crucial competencies and individualising the learning path while being supported by two experienced tutors — a certified academic tutor and a business mentor. BIPS (2023) is a two or three-semester work that involves both individual and team projects and provides an opportunity to create a community of active, committed individuals who are passionate and persistent in pursuing their goals.

Additionally, students are recruited into the Program from among all WUEB last-year students through a two-stage recruitment process based on three main criteria:

- initiative — activity in action, entrepreneurship, autonomy and creativity;

- ‘grit’ — perseverance, ability to pursue long-term goals, not letting go and seeing things through to the end;

- openness to others — altruism, empathy, selflessness, nobility and solidarity (BIPS, 2023).

In practice, the vast majority of the students representing the program are first-time business idea implementers, young entrepreneurs and professionals with above-average developed businesses and social competencies.

Furthermore, the sample frame included up to one individual representing each field of study and demographic criteria (Etikan, 2016). Ultimately, a total of nine interviews were conducted independently by the authoress in November and December 2022. There were five male and four female respondents, aged 21–24 years. The number of respondents represents almost 30% of all current BIPS participants, and owing to the fact that saturation point was reached, this size of sample was considered sufficient (Boddy, 2016; Sebele-Mpofu, 2020). All of interviews were recorded with the consent of the respondents, subsequently transcripted and translated into English and anonymised to maintain confidentiality.

Data analysis

Following the transcription and extraction of verbatim quotes, the thematic analysis method (Braun & Clarke, 2006) was used to analyse the data obtained. The method is based on inductive coding and searching for themes, and enables the identification, analysis and reporting of patterns (themes) within data. The data analysis procedure encompassed six steps:

- initial familiarisation with the data, as well as its transcribing, reading and re-reading;

- generating initial codes;

- searching for themes — collating codes into potential themes;

- reviewing themes and generating a thematic map of the analysis;

- defining and naming themes;

- producing the report (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

The results of the analysis carried out in this way are presented in the next section of the article.

Findings

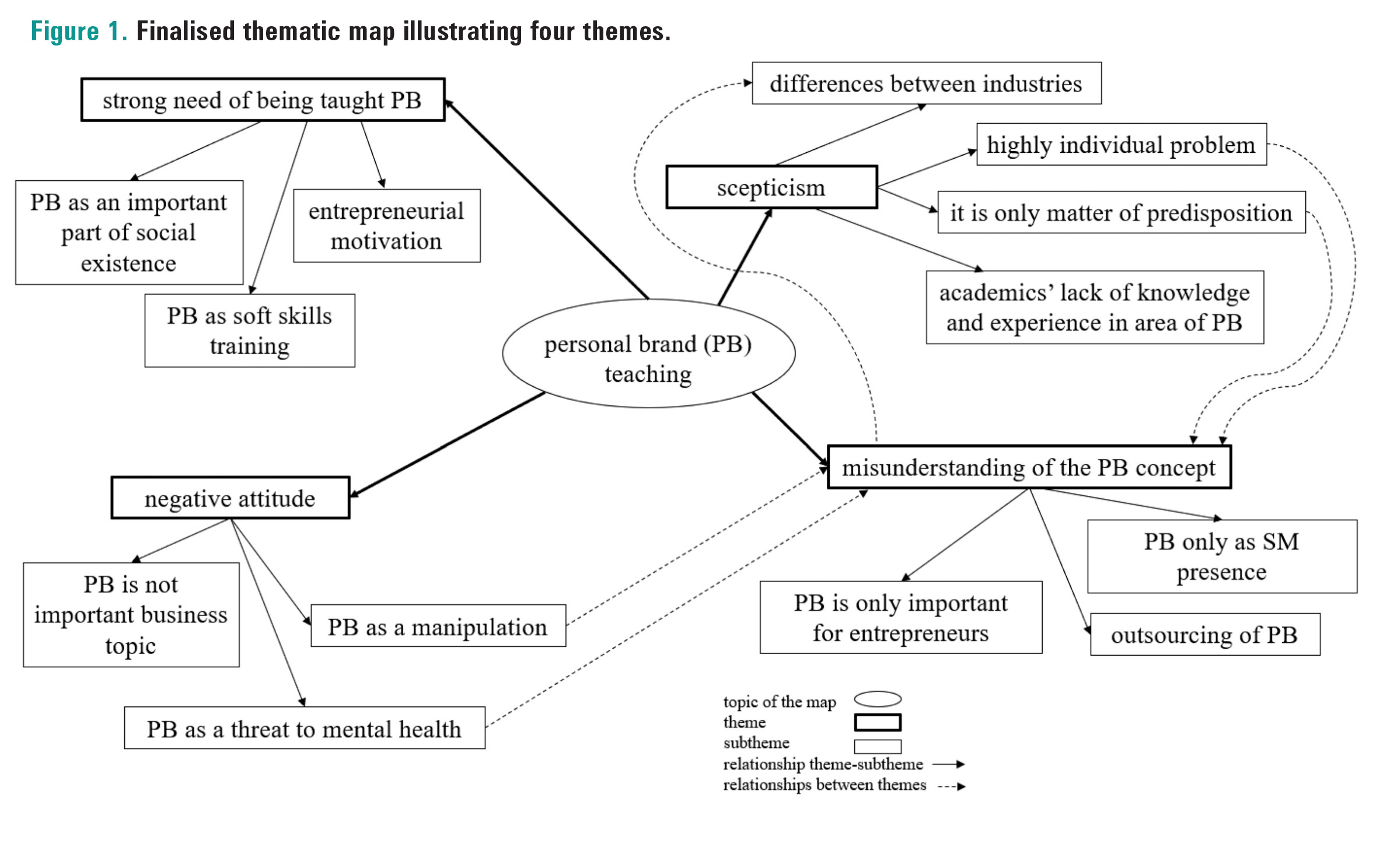

The thematic analysis process applied to the transcripts elicited vital concepts evident in the data. In the course of defining and naming themes, a final set of four higher order themes comprising 14 subthemes was identified. Four main themes that emerged were labelled as ‘Scepticism towards teaching PB’, ‘Negative attitude towards teaching PB’, ‘Strong need of being taught PB’ and ‘Misunderstanding of the PB concept’. These themes are viewed as essential in determining the understandings of all the participants about the need of students to be taught PB. There are, of course, aspects of the participants’ understandings that overlap across these categories. This, however, should be viewed as a reasonable interpretation of understandings and attitudes in general, which are never made up of isolated concepts but are all relative to each other.

Below, the authoress presents a detailed analysis of all themes and subthemes with examples of participants’ direct opinions. All quotes presented below (in italics) are statements made by respondents during the interview, translated into English by the authoress. All themes and subthemes are additionally presented on the graphic thematic map, which enables a better understanding of relations between themes and some overlaps (Figure 1).

Theme 1: Scepticism towards the teaching of PB

The first theme refers to the sceptic attitude of respondents towards the teaching of PB. In this theme, four subthemes were identified, which present students’ concerns about the possibility and quality of the teaching of PB at the university.

Subtheme 1.1: Differences in PB between industries

Respondents were concerned about differences in PB among various industries.

‘The same ways (of creating a personal brand) do not always work in different industries.’

Subtheme 1.2: Academics’ lack of knowledge and experience in the area of PB

Almost all of the respondents expressed concern about staffing issues — noting that PB should be taught by experienced practitioners with crosssector experience.

‘If it is to be a new course at the university, it must be taught by people who are up to date on the subject and preferably from different backgrounds. The same patents do not always work in various industries.’

Subtheme 1.3: PB as a matter of predisposition only

Some respondents believe that PB is an innate competence that cannot be learned.

‘It can be learned, but as with anything, someone may have a better or worse aptitude for it. I never learned about, nor was I interested in, the subject.’

Subtheme 1.4: Highly individual problem

Respondents mostly believe that PB is a very individual competency, and that it is not easy to teach all students in the same way, as each individual will need an emphasis on different aspects of the process.

‘It is possible to learn personal branding, but everyone requires slightly different learning, it is a very individual issue and it is impossible to know how to standardise it, for example in one course at the university.’

Theme 2: Negative attitude towards the teaching of PB

Some respondents spoke negatively about the concept of PB itself, which translates into their opinion concerning the lack of need for (Subtheme 2.1), or even the dangers (Subthemes 2.2 and 2.3) of teaching PB at universities.

Subtheme 2.1: PB is not the most important business topic

‘As for studies, the relevance of this issue is worth mentioning, but I believe it is not important enough to devote entire courses to it.’

Subtheme 2.2: PB as a manipulation

Among some respondents, there was a negative perception of PB as being part of the so-called ‘rat race’ and an identification of PB as an attempt to manipulate the environment.

‘In business universities, there is a big rush for legendary success. Teaching personal branding would be another step in this wrong direction. No one thinks about the real needs. Personal branding, in particular, serves to create an illusion and learns to put on a mask. In this way, some people learn to manipulate the environment.’

Subtheme 2.3: PB as a threat to mental health

Some respondents link PB with mental health, seeing the procedure (of formalising the teaching of PB by including the same within universitylevel academic curricula) as being harmful to people’s lives.

‘Instead of teaching students to create a personal brand, universities should take care of their mental health. Personal branding is a harmful pressure to a person’s psyche.’

Theme 3: Strong need of being taught PB

The third theme that was distilled highlights the significant motivations of students to acquire skills related to PB. Respondents see the process as a part of general social existence (Theme 3.1) or as a part of broader soft skills training (Theme 3.2). The most prominent thread, out of all those identified in the analysis conducted, is the entrepreneurial motivations for developing PB competencies (Theme 3.3).

Subtheme 3.1.: PB as an important part of social existence Several respondents understand the concept of the personal brand more broadly — in their opinion, PB goes beyond the business aspect.

‘(to create my PB), in particular, I care about good appearance, sincerity in communication, good interpersonal relations and my own

competence.’

Subtheme 3.2.: PB as soft skills training

Some respondents see PB as a set of soft competencies and believe that these should primarily be taught at the university.

‘Personal branding is really a set of soft skills, such as the ability to self-present. In my opinion, you need to teach these competencies in the first place.’

Subtheme 3.3.: Entrepreneurial motivation

The most prominent motivation for respondents is business issues. They view PB as a competitive advantage.

‘In business, many things are done through connections, and how people see you and remember you makes them likely to want to work with you in the future.’

‘(PB) helps show yourself and your business from a good point of view.’

‘As a future entrepreneur, I think this competence is essential for me.’

‘(When young professionals are taught PB, this will imbue them with) an ability to take care of themselves when taking a career path. Also, it will be easier for them to achieve the desired effect of their own business actions.’

‘Personal branding is important to networking to spread your wings in business.’

Theme 4: Misunderstanding of the PB concept

Although respondents generally demonstrated a great deal of knowledge and awareness of PB, some misunderstandings of the concept were evident in the interviews. As noted earlier, in the third theme, which represents a negative attitude towards PB, there were some statements based on erroneous or incorrect beliefs about PB. For example, PB can be seen as a manipulation or threat to mental health only if it is not understood correctly. However, those opinions were so strong that the authoress decided to include them in the category denoting an unequivocally negative attitude (Theme 2). In the following theme, the topics are grouped, showing mistakes in thinking about personal brand.

Subtheme 4.1: PB is only important for entrepreneurs

While the present analysis of respondents’ results make it evident that entrepreneurs need to cultivate a better awareness of the importance of crafting their brand image accurately, undergoing training pertaining to PB is unlikely to, by itself, result in a remediation of this shortcoming. It is scientifically proven that strategic PB can also benefit job seekers in the labour market. Meanwhile, some respondents believe that if they are not planning their own business venture, they do not need to invest time and effort in shaping their personal brand.

‘I do not care about my personal brand because I do not rely on developing my own business, and I think that in terms of my own business, it is more necessary than in the case of corpo-job.’

Subtheme 4.2: PB is only about social media presence

Another misunderstanding concerned with PB is an overly narrow, limiting view that it is primarily associated with online, social media presence. However, this viewpoint receives some amount of substantiation in light of the generally accepted conclusion that the role of the Internet and online social platforms is indeed crucial when it comes to PB, as evidenced by the fact that it is challenging to be a personal brand and remain digitally invisible at the same time, although there are various offline activities that are equally important.

‘I think it is enough to be on social media like LinkedIn, you do not need to learn it.’

Subtheme 4.3.: Outsourcing of PB

The third misunderstanding is related to the belief that a personal brand can be entirely delegated to an external entity for implementation. While there are, of course, agencies that handle PB, its subject must be aware of the critical aspects of the process and control the operations.

‘I completely fail to see the point of learning PB in college. If I need it because I’m going to be a famous politician or celebrity, I’ll hire myself a PR company.’

Conclusions

The detailed results above highlight some essential findings on how young professionals understand PB and to what extent they want to be taught the procedure. The four distilled themes discussed show that, in general, the need to gain personal brand skills is significant, and familiarity with the PB concept is widespread.

The key finding of this study is that it is evident that those respondents who present a negative attitude towards PB, or are sceptical towards it, usually misunderstand the concept — they perceive it in a way that is too narrow or completely incorrect, as well as inconsistent with the prevailing principles. This includes views of PB as manipulation or a threat to mental health. Of course, such phenomena do occur, but they result from pathological situations, and not from a properly understood PB process. Naturally, we can observe increasing scientific and popular-science discourse about the damage that PB may cause (Goldberg, 2022; Vallas & Christin, 2018), but still, this is the margin of the phenomenon.

In turn, many interviewees view PB as a ‘natural’ feature of the modern economy or as a set of practices and skills that any job seeker is obliged to master (RQ1). They understand that in a constantly changing business environment, PB is considered to be, as Loppis (2013) and Perkins (2015) have stated, a ‘leadership imperative’.

Scepticism about the teaching of PB at universities (RQ2) probably stems from the concerns and reservations that last-year students and young graduates generally have about the higher education system. This mainly refers to academicians’ lack of knowledge and experience in the business area, which, in the modern era, is a fundamental problem characterising the staff resources assigned for teaching of business subjects (including the teaching of PB) at universities. For this reason, the first step that is required to be taken in order to address the issue is to detect those skills and competencies needed by the labour market and only then try and adapt the curricula, accordingly. Educators need to present an interdisciplinary approach to make students more aware of market needs and teach them about the social processes and artefacts that influence perception, so that they can better create, maintain and control their personal brand (Montoya, 2002). This will primarily serve young entrepreneurs, who, in the survey, expressed a strong need to gain competence in PB, as they see it as their competitive advantage.

However, given the small sample size, caution must be applied and the findings might not be generalised. The picture of PB perception among young professionals is thus still incomplete, which encourages the authoress to conduct further research in this area.

References

1. Allison, L., Blair, J., Jung, J. H., & Boutin, P. J. (2020). The impact and mediating role of personal brand authenticity on the self-actualization of university graduates entering the workforce. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 28(2), 3–13.

2. Baluku, M. M., Kikooma, J. F., & Kibanja, G. M. (2016). Psychological capital and the startup capital — entrepreneurial success relationship. Journal of Small Business and Entrepreneurship, 28, 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/08276331.2015.1132512

3. BIPS. (2023). About BIPS. https://www.ue.wroc.pl/kandydaci/16198/o_programie.html [access: 31.05.2023]

4. Boddy, C. R. (2016). Sample size for qualitative research. Qualitative Market Research, 19(4), 426–432. https://doi.org/10.1108/QMR-06-2016-0053

5. Boyatzis, R. E. (2006). Using tipping points of emotional intelligence and cognitive competencies to predict financial performance of leaders. Psicothema, 18(1), 124–131.

6. Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

7. Campbell, S., Greenwood, M., Prior, S., Shearer, T., Walkem, K., Young, S., Bywaters, D., & Walker, K. (2020). Purposive sampling: Complex or simple? Research case examples. Journal of Research in Nursing, 25(8), 652–661. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744987120927206

8. Chatterjee, N., & Das, N. (2015). Key psychological factors as predictors of entrepreneurial success: A conceptual framework. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 21(1), 105–117.

9. Culo, I., Tkalec, G., & Borcic, N. (2022, October 1–2). The role of personal branding in contemporary. https://doi.org/10.14596/pisb.2861

10. Deloitte Access Economics. (2017). Soft skills for business success. https://www2.deloitte.com/au/en/pages/economics/articles/soft-skills-businesssuccess. html [access: 31.05.2023]

11. Edmiston, D. (2014). Creating a personal competitive advantage by developing a professional online presence. Marketing Education Review, 24(1), 21–24. https://doi.org/10.2753/mer1052-8008240103

12. Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of convenience sampling and purposive sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/ 10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

13. Eurofound. (2022). Living and working in Europe. https://doi.org/10.2514/6.2008-800 14. Frank, H., Lueger, M., & Korunka, C. (2007). The significance of personality in business start-up intentions, start-up rialization and business success. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 19(3), 227–251. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/08985620701218387

15. Gibb, A., & Ritchie, J. (1982). Understanding the process of starting a small business. International Small Business Journal, 1(1), 26–45.

16. Goffman, E. (1959). The presentation of self in everyday life. Doubleday.

17. Goldberg, E. (2022). Burned out on your personal brand. New York Times. [access: 31.05.2023]

18. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/10/20/business/influencer-burn-out-jobs.html

19. Gorbatov, S., Khapova, S. N., & Lysova, E. I. (2018, November). Personal branding: Interdisciplinary systematic review and research agenda. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02238

20. Ilies, V. I. (2018). Strategic personal branding for students and young professionals. Cross-Cultural Management Journal, XX(1), 43–51.

21. Johnson, K. M. (2017). The importance of personal branding in social media: Educating students to create and manage their personal brand. International Journal of Education and Social Science, 4(1), 21–27.

22. Jones, B., & Leverenz, C. (2017). Building personal brands with digital storytelling ePortfolios. International Journal of EPortfolio, 7(1), 67–91.

23. Khedher, M. (2014). Personal branding phenomenon. International Journal of Information, Business and Management, 6(2), 29–40.

24. Llopis, G. (2013). Personal branding is a leadership requirement, not a self-promotion campaign. https://www.forbes.com/sites/glennllopis/2013/04/08/personal-branding-is-aleadershiprequirement-not-a-self-promotion-campaign/?sh=85d1531226fa [access: 31.05.2023]

25. Lorgnier, N., & O’Rourke, S. (2011). Improving students communication skills and awareness online, an opportunity to enhance learning and help personal branding. In 5th International Technology, Education and Development Conference, 7–9 March, 2011, Valencia, Spain 1008–1015.

26. Manai, A., & Holmlund, M. (2015). Self-marketing brand skills for business students. Marketing Intelligence and Planning, 33(5), 749–762. https://doi.org/10.1108/MIP-092013-0141

27. McCorkle, D. E., & McCorkle, Y. L. (2012). Using LinkedIn in the marketing classroom: Exploratory insights and recommendations for teaching social media/networking. Marketing Education Review, 22(2), 157–166. https://doi.org/ 10.2753/mer1052-8008220205

28. Montoya, P. (2002). The personal branding phenomenon: Realize greater influence, explosive income growth and rapid career advancement by applying the branding techniques of Oprah, Martha and Michael. Personal Branding Press.

29. OECD. (2021). OECD skills outlook 2021. https://doi.org/10.1787/0ae365b4-en

30. Perkins, R. (2015). Entrepreneurial leadership theory: An exploration of three essential start-up task behaviors. In C. Ingley, & J. Lockhart (Eds.), Proceedings of the 3rd international conference on management leadership and governance (ICMLG 2015) (pp. 215–223). Academic Conferences Ltd.

31. Sebele-Mpofu, F. Y. (2020). Saturation controversy in qualitative research: Complexities and underlying assumptions. A literature review. Cogent Social Sciences, 6(1). 1– 17https://doi.org/10.1080/23311886.2020.1838706

32. Shepard, I. D. H. (2005). From cattle and coke to Charlie: Meeting the challenge of self marketing and personal branding. Journal of Marketing Management, 21, 589–606. https://doi.org/10.1362/0267257054307381

33. Stanton, A. D., & Stanton, W. W. (2013). Building “Brand Me”: Creating a personal brand statement. Marketing Education Review, 23(1), 81–86. https://doi.org/ 10.2753/mer1052-8008230113

34. Udemy Business. (2022). Workplace learning trends report 2022. https://business.udemy.com/2022-workplace-learning-trends-report/ [access: 31.05.2023]

35. Vallas, S. P., & Christin, A. (2018). Work and identity in an era of precarious employment: How workers respond to “personal branding” discourse. Work and Occupations, 45(1), 3–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/0730888417735662

36. Wetsch, L. R. (2012). A personal branding assignment using social media. Journal of Advertising Education, 16(1), 30–36. https://doi.org/10.1177/109804821201600106

37. Yankov, B., Ruskov, P., & Haralampiev, K. (2014). Models and tool for technology start-up companies success analysis. Economic Alternatives, 3, 15–24.

38. Zaech, S., & Baldegger, U. (2017). Leadership in start-ups. International Small Business Journal, 35(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242616676883

39. Zhao, X. (2021). Auditing the “Me Inc.”: Teaching personal branding on LinkedIn through an experiential learning method. Communication Teacher, 35(1), 37–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2020.1807579

Joanna Macalik — PhD in management and quality sciences, assistant professor in the Department of Marketing Management at the Wroclaw University of Economics and Business, Public Relations practitioner, art historian. Academically involved mainly in marketing communication, personal branding and employer branding. Works also as design thinking facilitator and academic tutor.