- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

The universities and business cooperation — a look from the caucasus countries

Devi Shonia1, Dariusz M. Trzmielak2*

1 Sokhumi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia

2 Management Faculty, University of Lodz

E-mail: dariusz.trzmielak@uni.lodz.pl

Trzmielak ORCID 0000-0002-4455-8845

Shonia ORCID 0000-0001-9801-1039

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0023

Abstract:

Historically, the Caucasus has always been the object of special interest of dominant international actors due to its favourable geographical location. Such interest continues today. Despite the difficulties in the region (internal conflicts, different economic and political environments), the Caucasus countries-Georgia, Armenia and Azerbaijan-are taking significant steps towards establishing close and solid relations with the European Union (EU), improving the economy, and improving politics. The purpose of this article is to analyse the elements of industry and science cooperation. The university and business cooperation is seen as a very complex field and an important component of the country’s innovative ecosystem which has long been the subject of research and analysis. The presented article provides for a study of the innovation ecosystem and its infrastructure in the countries of the Caucasus, and mechanisms for the development of the university and businessm cooperation (UBC) process, which is of particular importance for these countries, which are characterized by very low rates of innovation and competitiveness.

MINIB, 2022, Vol. 46, Issue 4

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0023

P. 93-114

Published December 30, 2022

The universities and business cooperation — a look from the caucasus countries

Introduction

Various ongoing global events, the scientific-technological revolution, economic and social crises, and problems caused by the pandemic have intensified the race for knowledge development worldwide to achieve competitiveness and economic growth. The universities in the Caucasus countries also conducted research, although their task (or main interest) was not to ensure that the results of the research would apply to society. By combining university research and business, while simultaneously involving the public and private sectors in the research process, it will be possible to develop the real sector of the region, discover successful products and achieve economic growth (Dhebar, 2016).

In the countries of the region, there is a different, but clear increase in expectations from universities, which should create such human resources that can initiate and implement innovative processes-with discoveries and technologies based on them.

Rising expectations from universities and their role in the country’s innovation ecosystem and economic development increase the relevance of UBC’s research. A modern university should be a flexible incubator for startups and technology transfer.

UBC is any interaction between universities and businesses for mutual benefit and is considered an important driver of the knowledge-based economy and society, as UBC can solve the organizational problems of universities and businesses, and therefore the current social and economic problems of the country.

The article is theoretical and analytical in nature. The basic research method is the analysis of the literature on the subject, statistical data and documents of the European Commission and government materials of the analysed countries. The results of the analysis can be used in the economic practice of scientific and research organisations, especially in the business environment sector, which is considered a bridge between science and business. The implementation of scientific projects with a foreign partner is a very important part of the internationalisation of the activities of business support institutions and is crucial for the development of researchers’

careers. The article indicates the ecosystem for the development of longterm systemic relations in the area of internationalisation, and support for the mobility of scientists in the implementation of research projects, carried out jointly by international partners. The analysis of ecosystems in Caucasus countries will show how to create knowledge so that universities and research centres are not perceived as producers of higher knowledge for themselves, without much contact with society.

And UBC’s full-spectrum research shows that:

- Why academic, research and entrepreneurial entities and business support institutions should work together;

- How universities and businesses can cooperate and how these activities are interconnected;

- What is the extent of the institutionalisation of UBC;

- What is the culture and vision for the development of such cooperation;

- Results of university, national/regional governments, and business influence on UBC;

- The university’s innovative ecosystem, startup ecosystem, and its formation-development process;

- The operation of the mechanisms for promoting the development of UBC, identifying problems, and eliminating the hindering factors and the features of their interdependence/impact.

The Universities and Business Cooperation — Theoretical Background

The role of science has become better understood by entrepreneurs.

Governments promote R&D through direct and indirect support (grants and tax subsidies, public infrastructures development) (Wilson, 2005). In the oldest surviving poem by Georgian poet Shota Rustaveli, The Knight in Tiger’s Skin, we find a maxim that may convey the importance of cooperation between science and business ‘He who does not seek a friend is an enemy to himself’ (Rustaveli, 2016). The claim touches on an issue that is universal and has accompanied man since time immemorial. Beyond that, when analysing the concept of cooperation, we have to face questions about the possibility of understanding two worlds governed by different ‘institutional logics’ (Sijde, Firmansyah, Frederik, & Redondo, 2014), what unites and what divides them, as well as coexistence within the socioeconomic environment.

In the works of Trzmielak and Zehner (Dubinskas, 1988; Trzmielak & Zehner, 2011), it is also repeatedly stated that the scientist and the entrepreneur are immature market dreamers and mature realistic market managers.

In Europe and the United States, academic and business cooperation dates back to the 19th century. Through the efforts of the University of Cambridge (UK) and entrepreneurs, a spin-out company, Cambridge Instruments, was created by Horacy Darvin in1881(Cattermole & Wolfe, 1987). In the early 1980s, Cambridge was one of three clusters of new industry activity and research centres in the UK, along with London and central Scotland (Wissema, 2009). Among the many examples of European pioneers combining science and business, the venture of German chemistry professors Liebig, Hofmann and Ladenburg, who used chemical theory to develop an artificial fertiliser in the mid-19th century, stands out (Jackson, 2008). Although their business venture failed, Etzkowitz (2002) considers them forerunners of cooperation between the scientific and industrial communities. The Hatch Act (US) laid the legislative foundation for the development of an agricultural research centre. This idea, pioneering for the time, was intended to launch basic research that would be commercialised in the future. Interesting insights were indicated by Elizondo-Noeriega, Muńiz-Rivera, Mendoza-Enríquez, Aguayo-Téllez, and Güemes-Castorena (2014) regarding academic entrepreneurship and cooperation between science and business in countries influenced by U.S. trends, such as Mexico and other Latin American countries. The mentioned countries have less technological knowledge and this creates conditions of educational and technological vulnerability for entrepreneurship. However, these countries have a different cultural, educational, technological and socioeconomic context than the United States and some European countries. These societies are less dynamic and the transfer of knowledge, technology, capital, and goods and services is less dynamic. Hence, cooperation between the scientific and entrepreneurial communities involving doctoral students and academics faces serious problems. Young people are dropping out of education or not getting on the path of obtaining a degree. These trends paralyse national initiatives and delay in better understanding of science and business actors (Martins-Lastres & Cassiolato, 2005). In the countries of Central and Eastern Europe, a key element in the academic transition to cooperation between science and business along the lines of developed countries has become, in the first instance, the ability of universities to respond to the changing employment conditions of graduates. The drive for innovation and business competitiveness has subsequently resulted in interest in instruments for intensifying cooperation between science and business. Emerging opportunities for commercial cooperation between science and business with tangible results for both parties passed through the academic ‘gray area’, involving the implementation of outsourced tasks using university equipment and infrastructure (Matusiak, 2010).

However, the phenomenon of third-generation universities, which included cooperation with industry in their mission alongside science and teaching, began in the 1970s. The developed concept of economic policy assumed the need to support innovation processes, the development of the small and medium-sized enterprise sector and the active formation of an entrepreneurial culture. Within the framework of the measures taken, it is important to emphasise the strong preference for academic entrepreneurship dynamising changes in the science and research sector. Matusiak (2010) refers to this as opening up silos of knowledge and increasing the possibility of commercial use of developed knowledge resources. Etzkowitz (2008) still uses the term ‘capitalization of knowledge’, in the sense of building ties between the worlds of science and business. The capitalisation or otherwise commercialisation of knowledge causes universities to become important market players. Matusiak (2010) analyses the ‘entrepreneurial university’ in two dimensions:

- the entrepreneurial activity of the university itself in the commercialisation of its know-how,

- the business activity of those associated with the university.

Researchers of science-industry relations add also the concept of ‘entrepreneurial science’. Thorp and Goldstein (2010) scientific and research centres should be an enterprise for scientists, in which money is invested and which should bring a return on the invested capital.

The emerging knowledge economy has determined the emergence of new forms of science-intensive products and services. The current basis for industry-university cooperation was established, also enabling companies to become more competitive (Kamisi, 2000). ‘The entrepreneurial science’, on the other hand, is strongly linked to ‘knowledge transfer partnership’, which is an effective mechanism for cooperation between the two communities in question: science and industry (Howlett, 2010).

The corporation became more information-oriented and universities become more business-oriented. There emerged a novel class of human organisation: intellectual institutions (Kuhn & Munitz, 1988). Early involvement of business in cooperative efforts with universities speeds up commercial products or technology developments (Eller, 1988). In the XXIst century, there is little doubt that scientific and technological capacity is directly related to its education and training system (Wilson, 2005).

The traditional explanation for business cooperation is given by Badaracco (1991). Businesses seek cooperation to:

1. increase their competitiveness and revenue,

2. reduce the risk of operating in the market,

3. increase accessibility to resources and expand those they already have,

4. minimise barriers to entry into new markets or for new products on those already available. Książek and Pruvot (2011) further add the opportunity to learn from partners, especially the more experienced ones. We have to emphasise that the process of learning is key to shaping leaders of innovation and transfer of knowledge and technology from science to industry (Wiśniewska, Głodek, & Trzmielak, 2015).

Increasing the competitiveness of an enterprise is the natural operation of an organisation in the market (Jasiński, 2013). Reducing the risk of operation refers to operating in a selected, uncertain, market for R&D products.

Cooperation reduces risk and uncertainty associated with inappropriate management of the knowledge and technology commercialisation process. The reduction of uncertainty and risk also comes from linking the resources of partners (Silver, Pagaza, & Coraz-Flores, 2005; Maliszewska, 2017). Two trends emerging in the 1980s and 1990s, the emergence of science parks and spin-offs, should also be linked to increasing accessibility to resources and minimising barriers to entry into new markets or for new products. The first was the emergence of science parks encouraging scientists to collaborate with businesses as a new source of funding and market knowledge. The second was the emergence of spin-offs, which used the innovative activity of students and scientists to exploit intellectual property created at universities (Nadirkhanlou, Pourezzat, Gholipour, & Zehtabi, 2013).

However, we cannot overlook the many sceptical works and evaluations of cooperation between science and business. In the research of Trzmielak, Grzegorczyk, and Gregor (2016), we find the following main bases of scepticism for cooperation between science and business:

- the scientific dependence of research on the academic publication (track),

- the divergent mentality of scientists and entrepreneurs, which brings a passive attitude to cooperation,

- the level of scientific research that does not relate to the transferability of knowledge and technology to industry-scientism detached from the problems of the market.

- misalignment of external policies of universities and R&D institutes with the needs of the market,

- laws not adapted to the formation of academic companies.

The Knowledge Status of the Caucasian Countries —

The Global Secondary Data Analysis

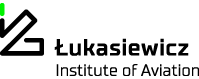

Based on the Global Knowledge Index (GKI) 2021 data, we see a real picture of the development of the knowledge society in the countries of the Caucasus (Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan), (Table 1).

The table shows that Azerbaijan is far behind Georgia and Armenia in higher education, scientific research, innovation, and development indicators. However, overall, the positions of all three countries of the region in this direction are unsatisfactory.

In terms of the Enabling Environment Index, with its strong economy, Azerbaijan lags far behind Armenia and Georgia, the leaders in this respect. Azerbaijan also lags behind Georgia and Armenia in terms of preuniversity/ educational education.

Universities can be key drivers of change and innovation, especially when interacting at the local, national and international levels. Universities and the entire higher education sector are uniquely positioned at the crossroads of education, research and innovation.

Cooperation between universities and businesses (UBC) is crucial in solving social problems, sharing and exchanging knowledge, building long-term partnerships, and stimulating innovation, entrepreneurship, and creativity.

UBC is key to stimulating innovation in higher education and a vital part of the overall Commission’s Directorate General for Education and Culture (DG EAC) policy in higher education (European Commission, Press release, 18 January 2022, Strasburg).

The main goal of DG EAC policy is to preserve and develop European values, as well as the participation of citizens in the European integration process. Its main tasks are:

- building a Europe of knowledge (lifelong learning programmes, promoting exchange programmes);

- preserve and develop cultural diversity in the EU in all forms;

- involve citizens in European integration processes to promote mutual understanding, trust and tolerance.

DG EAC targets all kinds of higher educational institutions, independent of their size and location, faculties and disciplines, and oriented national positioning. On the business side, it not only addresses companies (in particular small and medium enterprises — SMEs) but also public authorities, regions, cities, non-governmental organizations (NGOs), hospitals, museums, etc. in the EU and Erasmus countries.

The European Commission supports University Business Cooperation with several instruments, such as the Erasmus+ Alliances for Innovation (formerly Knowledge Alliances and Sectorial Skills Alliances) and the European Institute of Innovation and Technology (EIT).

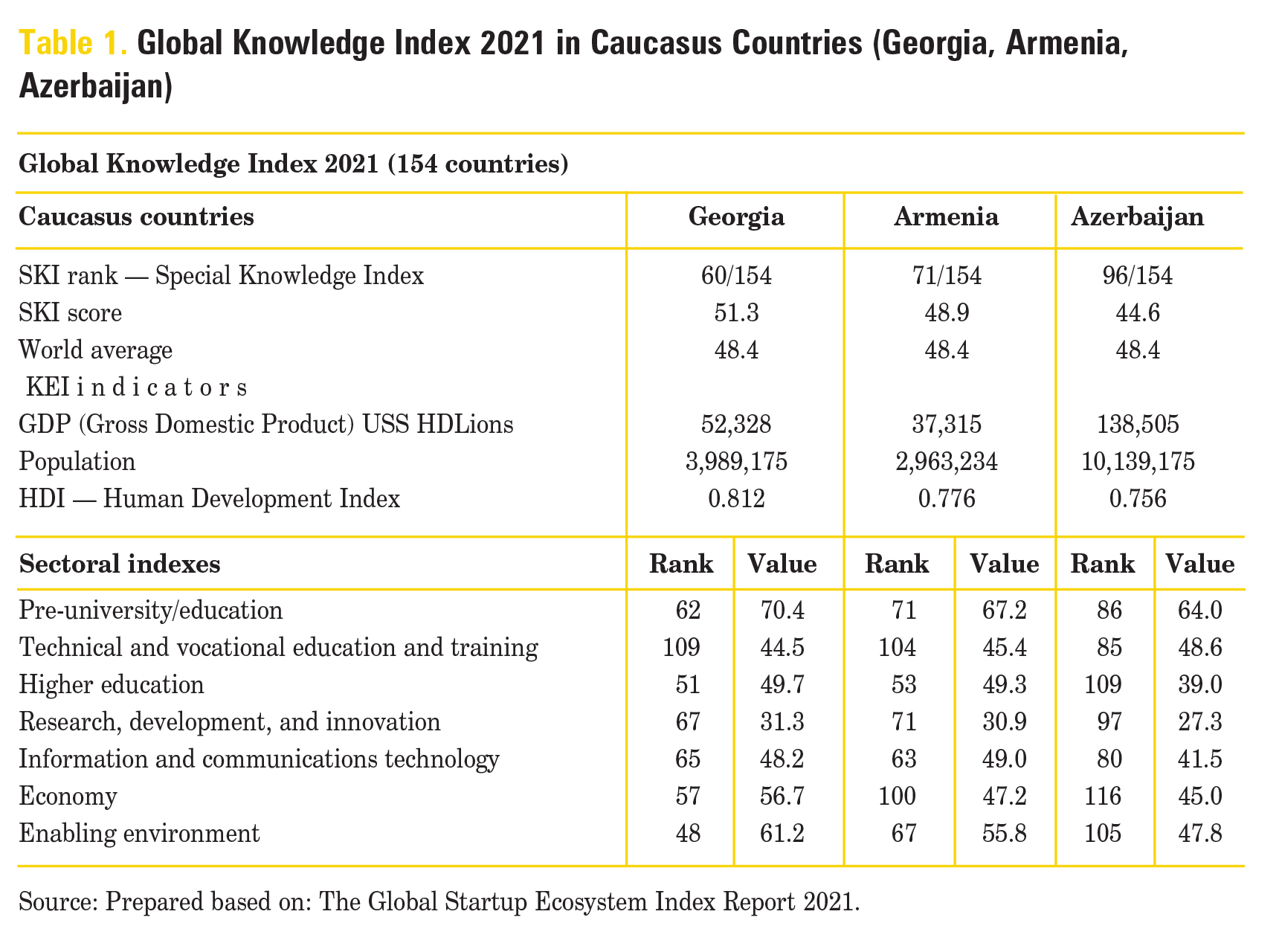

Since 2021, the European University Association (EUA), has started developing an evidence base for innovative activities of universities in Europe. EUA Solutions is a tailored service created to assist higher education institutions and stakeholders. (https://eua.eu). The association identifies different levels of innovation capacity in European universities and how these levels contribute to a wide range of impacts and social outcomes. Based on data from 166 institutions located in 28 European countries, the EUA and its Expert Group on Innovation Ecosystems can now provide a pan-European picture of innovation in universities, as well as key recommendations for universities, policymakers, and funding agencies to increase the contribution of universities to European innovation ecosystems. Thus, this policy position is an overview of how to support the growth of the innovative capacity of universities.

EUA plays a crucial role in the Bologna Process and in influencing EU policies on higher education, research and innovation. Through continuous interaction with a range of other European and international organisations, EUA ensures that the independent voice of European universities is heard.

By 2022, many universities in the Caucasus countries are members of the EUA, which means that they support its policies and express their readiness for active cooperation. (Table 2).

Despite significant efforts by European national governments and the European Commission to increase participation in UBC, there is a lack of understanding of how universities and businesses can work together and how these activities are (inter)linked. The perception of limited mutual benefits from cooperation reduces the usefulness of university training programmes for the labour market. The consequence is that university graduates are less likely to be employed according to their qualifications. The uncertainty of cooperation between science and business has an impact on the high risk of joint research.

A multi-stakeholder effort to increase UBC in Caucasus countries will have positive consequences for students, entrepreneurs, scientists, university authorities, and investors’ activities. The former will obtain employment opportunities under their competencies and skills acquired during their studies (which also reduces migration). The second will acquire personnel for the company’s development needs (which reduces the cost-quality personnel relationship) and ideas for innovation. The researchers can pursue increasingly ambitious research plans. The university authorities gain access to new sources of funding for science. The investors, in turn, reduce the risk of investing in R&D products, because UBC provides, in a sense, guarantees that university research is aligned with market needs.

It is recognised worldwide that university-business collaboration (UBC) is a complex and nonuniform field and its positive impact on economic outcomes has long been the subject of research and analysis in social sciences, innovation economics, entrepreneurship, marketing, and management scientific communities. UBC is an important component of the country’s innovation ecosystem.

The development of UBC requires a systematic and comprehensive study (of the innovation culture of the university, its ecosystem and development mechanisms, joint activities of the UBC operating model, and interconnected infrastructure elements (orientation to the common interests of the research process and UBC supporting mechanisms), mechanisms for identifying problems and removing obstacles.

The State of UBC in Europe study presents a mixed picture. To increase the low levels of cooperation, UBC needs to focus on drivers rather than barriers, the mechanisms of UBC need to be developed and aligned and relationships need to be placed at the core of UBC. In short, UBC needs to be seen as an ecosystem that requires careful management. For UBC to institutionalise and increase its impact, there should be a concerted effort between governments at national and regional levels, Higher Education Institutrion (HEI) and faculty boards, and business managers (Davey, Meerman, Muros, Orazbayeva, & Baaken, 2018).

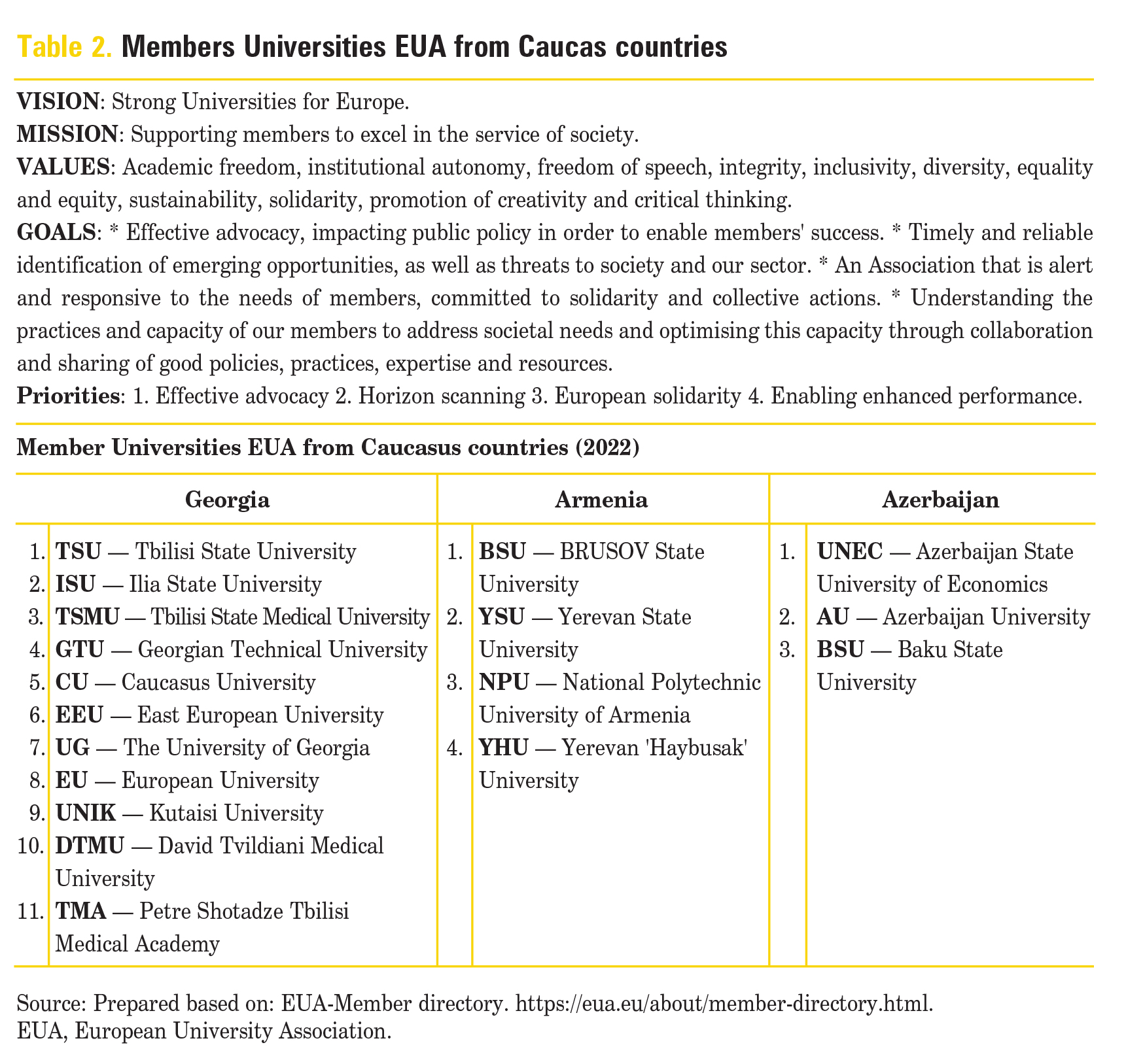

The Global Startup Ecosystem Index Report 2022 (The Global Startup Ecosystem Index Report 2022 report https://www.startupblink.com/ startupecosystemreport) shows rankings of Caucasian countries. Among the Caucasian countries, Armenia moved up to 60th place from 65th a year earlier, ahead of Georgia, which took 73rd position (against 80th a year earlier) and Azerbaijan-to 85th (against 89th a year earlier).

In particular, according to the source, in the presented indicators, 100 countries were evaluated according to 3 criteria: quantitative (the number of startups, co-working spaces, accelerators, and events dedicated to startups), qualitative (the presence of statistical branches and R&D, corporations, branches of transnational companies, the volume of the rating is overall penetration of individuals into the number of start-up ecosystems, the presence of large individuals-business angels, venture morbidity, etc.), and the business environment (Doing Business rating, and the speed of the Internet, censorship, investment in R&D-design work), etc.). (Table 3.).

In 2022, Yerevan entered the top 250 city ranking globally. Yerevan has seen a major jump, improving by 38 spots to 244th globally, and reversing its declining momentum from 2021. This increase pushed Yerevan up the ladder in Eastern Europe, where it is now ranked 19th, versus 29th in 2021. Yerevan is the highest-ranking city in the Caucasus region, with a safe margin. Its score is more than double Tbilisi’s score, and more than triple Baku’s score.

In the countries of the Caucasus, systems for developing opportunities for university start-ups are dynamically developing, the existence of most of which is less than 5–6 years. (Table 4.).

Armenia

Armenia Startup Academy cooperates with world-famous service startups, accelerators and incubators, venture capital companies, and business angels. Academy is focusing on building game-changing entrepreneurship and startup education programmes that will armour capable teams with knowledge and skills for building products that customers love.

The Entrepreneurship and Product Innovation Centre (EPIC) is a platform of the American University of Armenia (AUA) for promoting entrepreneurial education, cross-disciplinary collaboration, and startup venture incubation. EPIC provides an ecosystem for emerging entrepreneurs consisting of first-class facilities and collaborative workspace, programmes and events, and a network of mentors, advisors, and investors. EPIC fosters the understanding and application of entrepreneurship in students and faculty at AUA to craft high-impact multidisciplinary ventures.

By the decision of the independent jury of the entrepreneurship world cup (EWC) Armenia 2022 National Finals, two Armenian startups, Text’nPayMTopshop, took first place and will represent Armenia in the EWC Global competition. They will compete for a chance to win $1 million in prizes.

Text’nPayMe is a banking keyboard that enables bank clients to send money by way of any messaging application or other application that contains an input field.

Hopshop is Shazam for fashion. It helps customers find and purchase clothes or accessories that are available on the Internet and social media and even those they might spot others wearing on the street.

Azerbaijan

Organisations in Azerbaijan that help startups launch and develop their products.

SABAH.lab acceleration centre. The centre is part of the Education Institute of the Republic of Azerbaijan and is supported by the Ministry of Education of the Republic of Azerbaijan. SABAH.lab also hosts many events for startups.

Incubator and accelerator INNOLAND — the State Agency for Services to Citizens and Social Innovation under the President of Azerbaijan (ASAN), includes mentor support, networking, and the opportunity to use office space.

Acceleration programme Azerbaijan Innovation Centre — helps startups from Azerbaijan connect with Silicon Valley. The programme was founded in February 2020 by INNOLAND.

Programme of incubation of NEXT STEP innovation centre — As part of the programme, participants get access to coaching, create an Minimum Viable Product MVP, and develop their own business model.

Sup VC acceleration programme — acceleration programme, which allows startups to grow and enter international markets.

Georgia

The startup ecosystem of Georgia is just being formed, but in the country, especially in the capital, Tbilisi, there are many platforms where you can develop your project. Georgia’s Start-up ecosystem is promoted and developed through different platforms.

THE Crossroads — The innovative startup programme for women entrepreneurs was launched in December 2016 and its goal is to create a suitable environment for both startups and investors. To take part in this project, the company must be registered as a legal entity, and it must be managed by a female director or partner.

Innovfin from Pro credit bank. Implemented in cooperation with the European Investment Bank Group. ‘Relatively large innovative projects’ can take part in the programme.

Smartex from Liberty bank. This bank was the first in Georgia to create a startup incubator. Initially, the main areas in the incubator were e-commerce, telecommunications, and electronic payments. One of the projects that received funding under the programme was the startup Swoop.

The Spark Platform is a hub for people who have a business idea but no access to resources. The platform provides space for startups, helps startups calculate risks when developing a business plan and provides advice from financiers, marketers, and analysts. Works with such business areas as tourism, vocational and higher education, medical business, sports, health, IT, innovative business ideas, energy-efficient technologies.

Acceleration programme and coworking space Startup Factory from the Georgian University. The site is open 24/7, and the electronics and engineering lab, the Mobile Application Development Centre, and a stylishly designed space that can accommodate up to 40 people are available for startups.

Several university-based incubators are already operating in Georgia-at the Free University, at the Ili State University, and at the Georgian Technical University.

Since 2009, the Batumi Business Incubator has been operating — a project of the UN Development Programme, which is funded by the governments of Romania, Finland and the Autonomous Republic of Adjara (Batumi is the administrative centre of the Republic of Adjara, the Georgian autonomy). As part of the incubation programme, startups can get free advice on international trade, accounting, taxation, business organisation in a startup, financing, and logistics.

Silicon Valley Tbilisi (based on Business and Technology University) is the first private high-tech centre in Georgia, which combines a university, a business incubator and an accelerator, an IT academy and a media centre.

FasterCapital is an international incubator and accelerator with a portfolio of 20 certified startups, 69 incubation startups and 285 acceleration startups. It helps startups not only to work out their business ideas but also to get funding, and invites startups to become their technical co-founder. There are 3 startups from Georgia on acceleration at FasterCapital.

Startup Grind Tbilisi. A division of the world’s largest independent startup community of 2,000,000 entrepreneurs. The global sponsor of the organisation is Google for startups. Startup Grind Tbilisi hosts events where successful world-class startups share their experience; Startup Grind is also an opportunity to make useful contacts, and find investors and partners.

The universities of the Caucasus countries must make maximum use of the existing opportunities and development systems for university starters. It is possible to cite many such good examples, although their number is small in the region.

Center for Entrepreneurship and Product Innovative Products (CEPIP) of the American University of Armenia (AUA) together with the Entrepreneurship World Cup (EWC) National Leadership Committee at the EWC Armenia 2022 national finals, the main prizes were given to two Armenian startups Text’nPayMe and Hopshop who took first place and represented Armenia at the EWC Global Finals. They competed for the chance to win a $1 million prize.

Georgian startupper Ana Robakidze, the founder and CEO of the AI platform Theneo won a Pitch contest at the world’s largest technology event, Web Summit 2022 in Lisbon among 2,300 startups, representing hundreds of countries worldwide. ‘We are the first Georgian company to ever go this far in any kind of big startup competition. So I feel like it’s beyond just me or my company. It also represents a lot for my country. Unfortunately, not a lot of people know about the startup ecosystem in Georgia. There are so many great startups, and I feel like I’m also representing them’, Robakidze said.

Conclusions

In the countries of the Caucasus, more than ever, the awareness of the importance of innovation is constantly growing in society, where the

modern university is the main driving force.

The University and Business cooperation (UBC) is dynamically becoming an important component of the innovation ecosystems of the Caucasus countries, which requires a systematic and comprehensive study of the innovation culture of the universities, its ecosystems and development mechanisms.

To increase the low level of cooperation, UBC must focus on drivers rather than barriers, UBC mechanisms must be developed and agreed upon, and relationships must be placed at the heart of UBC.

One may assert that university and business cooperation arises from the necessity of finding non-state funding to carry out scientific research. We accentuate the fact that higher education institutions should establish spin-off companies or grant licences to companies for their most advanced innovations and R&D work. The model of academic companies is what can be applied in the countries of the Caucasus, particularly Armenia and Georgia, where small business entrepreneurship has its roots in distant history. Universities and research centres in Caucasian countries should not only generate research results but also seek out purchasers for them. This can be most effective if they consider the requirements of industry partners as early as the planning stage of the scientific research. We note that the creation of knowledge on technology at the university and research centres should also be combined with an analysis of future market trends and strategies for businesses.

UBC should be seen as an ecosystem that needs to be carefully managed. For UBC to institutionalise and increase its influence, a concerted effort is needed from national and regional governments, university and faculty boards, and business managers.

Too many universities in the Caucasus countries still do not properly understand the relevance of UBC and its role as an important component of the country’s innovation ecosystem. An important task for such universities should be the formation of an effective UBC model, the effective interaction of related elements and the improvement of development mechanisms. University leaders must be prepared to make strategic and operational decisions to build a successful UBC model based on research and excellence.

Universities of the Caucasus countries should be more committed to improving the opportunities for the development of start-ups and becoming part of the innovation ecosystems of the country and the world. They must express their readiness to create joint programmes in this direction, invite specialists, increase student mobility, and improve curricula in entrepreneurship, marketing and management.

References

1. Badaracco, J. L. (1991). The knowledge link: How firms compete through strategic alliances. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School, pp. 7–13.

2. Cattermole M. J. G., Wolfe A. F. (1987). Horace Darwin’s Shop, A history of the Cambridge Scientific Instrument Company 1878–1968, CRC Press.

3. Davey, T., Meerman, A., Muros, V. G., Orazbayeva, B., & Baaken, T. (2018). The state of university-business cooperation in Europe. European Union. Retrieved from https://www.ub-cooperation.eu/pdf/englishexec.pdf.

4. Dhebar, A. (2016, November–December). Bringing new high-technology products to market: Six perils awaiting marketers. Business Horizons, 59(6), 713–722.

5. Dubinskas, F. (1998). Making time: Ethno-graphics of high technology organizations. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press, s. 201.

6. Elizondo-Noriega, A., Muńiz-Rivera, G., Mendoza-Enríquez, N., Aguayo-Téllez, H., & Güemes-Castorena, D. (2014). Entrepreneur thinking, a brand-new methodology for start-ups. The ISPIM Americas Innovation Forum, Montreal 2014, Forum paper.

7. Eller, D. G. (1998). Innovative science and traditional industry: New Vision in Agritecgnology, pp. 597–601.

8. Etzkowitz, H. (2008). The triple helix: University-industry-government innovation in action. New York, NY: Routledge, pp. 27–43.

9. Etzkowitz, H. (2002). MIT and the rise of entrepreneurial science. London–New York: Routledge, p.10.

10. European Commission, Press release. 18 January 2022, Strasburg, France. Retrieved from https://european-union.europa.eu/institutions-law-budget/institutions-and-odies institutions-and-bodies-profiles_en.

11. European University Association. The Voice of Europe’s Universities. Nonprofit Organisation. 1040 Brussels, Belgium. 1211 Geneva 3. Switzerland, Europe. Retrieved from https://eua.eu/.

12. Global Knowledge Index 2021. United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), Regional Bureau for Arab States (RBAS). One United Nations Plaza, New York, NY10017, USA and Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum Knowledge Foundation (MBRF). Dubai World Trade Center, Dubai, 214444. Retrieved from UAE.

www.knowledge4all.org.

13. Howlett, R. J. (2010). Knowledge transfer between UK universities and business. In R. J. Howlett (Ed.), Innovation through knowledge transfer (pp. 1–14). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

14. Jackson, C. M., (2008). Analysis and synthesis in nineteenth-century organic chemistry. UCL University of London Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the PhD degree of the University of London, December 2008.

15. Jasiński, A. H. (2013). Aktywność badawczo-rozwojowa przedsiębiorstw kluczem do wzrostu innowacyjności gospodarki. In Przedsiębiorczość — droga do innowacyjnej gospodarki, SOOIPP Annual 2013, Zeszyty Naukowe nr 795, Ekonomiczne Problemy Usług, no 109, Uniwersytet Szczeciński, Szczecin 2013, pp. 13–27.

16. Kamisi, Y. (2000). Industry-university linkage and the role of universities in the 21st centry. [w:] P. Conceiçao, D. Gibson, M. Heitor, & S. Shariq (Eds.), Science technology and innovation policy: Opportunities and challenge for the knowledge economy (s. 87–98). London, England: Quorum Books.

17. Książek, E., & Pruvot, J. M. (2011). Budowanie sieci współpracy i partnerstwa dla komercjalizacji wiedzy i technologii. Poznań–Lille: PARP, pp. 41–58.

18. Kuhn, R. L., Munitz, B. (1988). The emergence of intellectual institutions: Producing new knowledge in industry and academia. [w:] R. L. Kuhn (Ed.), Handbook for creative and innovative managers (pp. 569–576). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill Book Company.

19. Maliszewska, E. (2017). Zarządzanie ryzykiem reputacji — problem definicji i pomiaru, [w:] Zarządzanie ryzykiem instytucji finansowych. Problemy Zarządzania, 15(1), 79–91.

20. Martins-Lastres, H. M., & Cassiolato, J. E. (2005). Innovation policies in the knowledge era: A South American perspective. In: D. V. Gibson, M. V. Heitor, & A. Ibarra-Yunez (Eds.), Learning and knowledge for the network society (pp. 57–72): Purdue University Press.

21. Matusiak, K. B. (2010). Budowa powiązań nauki z biznesem w gospodarce opartej na wiedzy. Rola i miejsce uniwersytetu w procesach innowacyjnych. Warszawa, Poland: Szkoła Głowna Handlowa, pp. 87–92.

22. Nadirkhanlou, S., Pourezzat, A. Gholipour, A., & Zehtabi, M. (2013). Requirements of knowledge commercialization in universities and academy entrepreneurship. In R. J. Howlett, B. Gabrys, K. Musial-Gabrys, & J. Roach (Eds.), Innovation through Knowledge Transfer 2012 (pp. 179–194). Heidelberg, Germany: Springer.

23. Rustaveli, S. (2016). The knight in the Panther’s skin. Badri Sharvbadze.

24. Sijde, P., Firmansyah, D., Frederik, H., & Redondo, M. (2014). University-business cooperation: A tale of two logics. Moderne Konzepte des organisationalen Marketing: Modern Concepts of Organisational Marketing, Springer Fachmedien Wiesbaden, pp. 145–160.doi:10.1007/978-3-658-04680-4_9

25. Silver Pagaza, G., & Coraz-Flores, E. (2005). The agency problem of R&D projects.

In D. Trzmielak, & M. Urbaniak (Eds.),Technology policy and innovation. Valueadded partnering in a changing world (p. 155). Łódź, Poland: American-Polish Offset Program University of Texas at Austin — University of Łódź.

26. Thorp, H., & Goldstein, B. (2010). Engines of innovation: The entrepreneurial university in the twenty-first century. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press, pp. 22–38.

27. Trzmielak, D. M., Grzegorczyk, M., & Gregor, B. (2016). Transfer wiedzy i technologii z organizacji naukowo-badawczych do przedsiębiorstw. Łódź, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, p. 93.

28. Trzmielak, D. M., & Zehner, W. B. (2011). Metodyka i organziacja doradztwa w zakresie transferu i komercjalizacji technologii. Łódź–Austin: PARP, p. 127.

29. Wilson, R. H. (2005). Development policy and the economy: Whither the state? In D. V. Gibson, M. V. Heitor, & A. Ibarra-Yunez (Eds.), Learning and knowledge for the network society (pp. 73–97): Purdue University Press.

30. Wiśniewska, M., Głodek, P., & Trzmielak, D. (2015). Wdrażanie scoutingu wiedzy w polskiej uczelni wyższej. Aspekty praktyczne. Łódź, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego, p.33.

31. Wissema, J. G. (2009). Uniwersytet Trzeciej Generacji. Uczelnia XXI wieku. Święta Katarzyna, Poland: Wydawnictwo Zante, p.35.

Prof. Dariusz M. Trzmielak — He is Deputy Director of Polish Mother’s Memorial Hospital Research Institute for Scientific Affairs and an expert in knowledge management, transfer of intellectual property from scientific and research centers to enterprises. He worked for the American-Polish Offset Program at the University of TexasUniversity of Lodz from 2004 to 2007, as Director of the Innovation Center. From 2010 to 2014, he served as a member of the investment committee of the StartMoney Fund. He also managed, as Vice President of the Board of Directors, the Innovation Center — Technology Accelerator Foundation of the University of Lodz. He also used his knowledge and experience in managing the Technology Transfer Center of the University of Lodz. In international activities, he is a member of the Fellows Network of the University of Texas at Austin. He served on the board of the Technology Accelerator Foundation of the UŁ Foundation and the board of directors of the biotechnology company GeneaMed Ltd. For nine years he was a member of the board of directors (Vice President and Board Treasurer) of the Association of Organizers of Innovation and Entrepreneurship Centers in Poland and a member of the scientific council of the Proakademia Research and Innovation Center.

Devi Shonia — Ph.D. Associate Professor at the Faculty of Business and Social Sciences, Sukhumi State University, Tbilisi, Georgia. In 2016, within the Mobility Erasmus Program, he was a post-doctoral fellow at the Faculty of Management of the University of Lodz. Teaches training courses: “”Basic of Marketing””, “”Consumer Behavior””, “”Strategic Marketing””. He is the author of over 20 scientific articles and two textbooks (in Georgian). The main research area: Marketing research, analysis, modeling, and implementation of strategies of innovative products and brand development. Devi Shonia is a member of the editorial board of journals: “”Business and Management”” (Georgia) and “”Marketing of Scientific and Research Organizations”” (Poland). Also, he is a member of the Academic Council of Sukhumi State University and a member of the Expert Corps for the Quality Development of Higher Education in Georgia.