- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Polish Gen-Z consumers’ attitudes to corporate social responsibility (CSR)

Mirosław Pacut

Faculty of Management, Department of Marketing, University of Economics in Katowice,

1 Maja 50, 40-287 Katowice, Poland

E-mail: miroslaw.pacut@ue.katowice.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-6494-5167

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0017

Abstract:

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a management concept that has emerged in response to society’s growing sensitivity to the negative externalities of economic activity. The market success of contemporary enterprises is no longer determined solely by their ability to innovate and select tools for shaping their market positions, but also by their capability to define their roles within the social environment of which they are undoubtedly a part. This article aims to explore how Polish Generation Z consumers perceive and respond to CSR initiatives implemented by enterprises. Understanding their perspectives is particularly crucial, given that the attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of this demographic will soon significantly influence market landscapes and enterprises’ potential to attain success in them. The findings reveal that young Polish consumers place considerable importance on corporate social responsibility. This significance is reflected in their overall attitudes towards CSR initiatives and their willingness to actively support these efforts, such as through their market choices.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 53, Issue 4

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0017

P. 80-97

Published September 12, 2024

Polish Gen-Z consumers’ attitudes to corporate social responsibility (CSR)

1. Introduction

Today’s dynamic economic landscape is characterized by rapidly changing conditions that require companies to not only engage in continuous innovation to develop and refine tools for shaping their market positions, but also to define their own roles within the broader socio-economic context. Various challenges, including globalization, environmental degradation, significant social shifts, and heightened competition (Wołoszyn et al., 2012), are compelling modern enterprises to align their business strategies with stakeholder expectations, addressing both the external impacts of their activities and their responsibilities toward societal issues.

While the idea of taking such action gained significant social recognition only in the latter half of the last century, it is not new – it traces back to a 150-year-long debate on business values and ethics, originally focused on fair treatment of business partners, a commitment to philanthropy, and ensuring decent working and living conditions for employees. This debate intensified as businesses expanded, which in turn amplified their influence on overall social well-being (Baran, 2021). A critical aspect of this context was the growing criticism of corporations, as they stood increasingly accused of engaging in predatory and anti-social behaviors in pursuit of business gains, leading to economic instability and inefficient, environmentally damaging resource management.

Increasing social awareness (including consumerism, environmental movements, human rights movements, etc.) has led to the gradual development of a modern, broader understanding of corporate social responsibility (CSR), emphasizing the multifaceted impact of business activities on the social environment, as well as the importance of these actions in achieving the economic objectives of enterprises. Contemporary societies are increasingly unwilling to accept (let alone support) organizations whose goals are not aligned with (or even contradict) broader social interests.

The aim of this article is to explore the cognitive and behavioral attitudes toward corporate social responsibility among young Polish consumers representing Generation Z – a particularly interesting group, given that they are highly sensitive to the various social and environmental consequences of human activity (Zakusilo, 2021), while also being at the early stages of their adult lives. As such, their attitudes, preferences, and behaviors can be expected soon to play a critical role in shaping market landscapes and determining the success of businesses.

2. Corporate Social Rresponsibility (CSR)

Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) is a management concept that takes into account the external effects of business activities – effects traditionally overlooked in economic calculations – particularly their impact on the natural and social environment. It also emphasizes the importance of transparency and ethical relationships with various stakeholder groups. At the foundation of this concept is the need to ensure the sustainable functioning of enterprises at the intersection of three spheres: economics, environmental care, and social development (Demkow & Sulich, 2017). As such, the CSR concept aligns with the current trends of increasing social awareness and heightened sensitivity to the negative non-economic aspects of business activities, such as environmental degradation, excessive exploitation of raw material resources, worker exploitation, and profit-making at the expense of local communities through practices like tax avoidance or not utilizing local suppliers and contractors.

It is important to note, however, a certain duality in the understanding of CSR. While the kinds of actions undertaken under the concept of CSR are universally recognized, the motivations understood to be lying behind these actions may vary. One approach stems from social contract theory, which posits that companies adopt responsible behavior out of moral and ethical considerations (Davis & Blomstrom, 1966), reflecting a duty to fulfill various obligations to society as a “corporate citizen” (Carroll, 1991). On the other hand, it is clear that all business activities are driven by commercial motives, with the primary purpose being to achieve economic outcomes. This perspective, rooted in shareholder theory, views CSR activities simply as a set of tools serving purely business objectives, such as shaping the organization’s image, strengthening its competitive position, and boost sales. At the same time, it acknowledges that the social environment sets the rules of the market game and conditions the achievement of these goals (Friedman, 2008; Kazojć, 2012).

This duality is not, of course, a simple dichotomy. Every business operates within a social environment – business decisions have consequences, including the generation of external effects that impact society. In turn, the social environment and public opinion significantly influence the scope of an enterprise’s ability to achieve its economic goals. This approach is conceptualized in stakeholder theory, which posits that a company should be oriented toward meeting the needs of all stakeholder groups (Freeman et al., 2004) – both those with whom the company has purely business relationships (and on whom it directly depends for achieving its economic goals) as well as those who directly or indirectly experience the external effects generated by the company’s activities and who constitute its social environment (Argandoña, 1998). Stakeholders include both internal groups (owners, shareholders, employees, management) and external groups (customers, suppliers, intermediaries, competitors, market institutions, government and local authorities, as well as social organizations, interest groups, local communities, and, ultimately, society at large) (Lozano et al., 2014).

The diversity of a company’s stakeholder groups, whose often differing interests must be considered when designing strategies, is reflected in the broad definition of the areas of action undertaken within the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR). Carroll (1991) proposed to classify these actions into four areas – economic, legal, ethical, and philanthropic – arranged in a hierarchical structure. In this model, economic aspects form the base of a pyramid, upon which the subsequent elements – law and ethics – are built, with philanthropy at the apex. Note, however, that the inclusion of philanthropy in this classification is debated, with some authors arguing that it should not be considered a component of corporate social responsibility (L’Etang, 1994). These areas often overlap and intersect, with CSR activities being classified as belonging to various combinations of these domains (Schwartz & Carroll, 2003). Other general classifications of CSR areas include R.W. Griffin’s (2004) concept, which identifies social welfare, the natural environment, and the needs of external stakeholders, or the triad model – focusing on the environment, economy, and society (He, 2018) – as well as a similar concept that highlights the environment, quality of life, and legal aspects as key CSR areas (Socorro-Marquez et al., 2023).

More detailed classifications, especially in relation to the practical aspects of business operations, are provided by international organizations. For instance, the OECD (2023) outlines CSR areas including information transparency, human rights, employee relations, the environment, anti-corruption, consumer interests, science and technology, competition, and taxation. Similarly, the International Organization for Standardization (ISO) defines seven CSR areas in its ISO 26000 standard: organizational governance, human rights, labor practices, the environment, fair operating practices, consumer issues, and community involvement (PKN, 2012).

Incorporating CSR initiatives into business practices can offer companies a variety of benefits that indirectly boost their economic performance (Leoński, 2015). Among the most significant are image-related advantages, such as building social legitimacy (Du et al., 2012), cultivating trust (Crane, 2020), and fostering favorable attitudes (Hansen et al., 2011) among different stakeholder groups. These factors contribute to enhancing the organization’s social capital, which in turn facilitates easier access to valuable resources, collaboration opportunities, and the support of public institutions. Furthermore, and perhaps most critically, CSR activities can shape consumer behavior by influencing how they perceive products (Berens et al., 2005; Brown & Dacin, 1997), driving engagement (Agyei et al., 2021), encouraging purchase intent (Lee et al., 2013), and building loyalty (Howaniec, 2016) and satisfaction (Luo & Bhattacharya, 2006).

It is particularly important to highlight the significant impact of CSR on consumers. While meeting the needs of other stakeholder groups and maintaining good relationships with them lays the foundation for a potential competitive advantage, turning this potential into a real advantage depends on market validation, which is ultimately determined by consumers’ purchasing decisions. Given the growing sensitivity of modern societies – especially among younger generations – to issues related to sustainable social development, how consumers perceive corporate responsibility in this area is increasingly crucial for securing the desired economic benefits. In some cases, it is even a prerequisite necessary for market success.

3. Research methodology

To identify and analyze the attitudes, perceptions, and responses of young consumers toward various activities within the framework of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), we carried out a direct study using an online survey method, targeting a purposive-convenience sample of 94 individuals, in November 2023. Initially, 98 completed surveys were received, but 4 respondents were excluded from further analysis as they did not meet the age criterion (18–28 years).

The survey began with an explanation of the CSR concept and a description of the associated activities. The main section of the questionnaire included a series of statements designed to assess general cognitive attitudes toward CSR. Additionally, there were three groups of questions aimed at evaluating the impact of CSR activities in specific areas on: (1) the development of trust in the company, (2) the respondents’ willingness to support companies engaged in such activities, and (3) their willingness to pay higher prices for products from companies demonstrating social responsibility. The survey also included demographic questions and inquiries about the respondents’ views on the preferred model of socio-economic governance.

The questions were based on 7-point Likert scales with descriptive endpoints. For the question assessing general cognitive attitudes, the endpoints were “I disagree” (1) and “I agree” (7). For the question regarding trust in companies practicing CSR, the endpoints were “does not increase my trust in the company at all” (1) and “significantly increases my trust in the company” (7). For questions assessing the likelihood of the participant’s supporting CSR activities, the endpoints were “very unlikely” (1) and “very likely” (7). The question about the preferred model of socio-economic governance had endpoints described as “the well-being of society should be ensured by the state” (1) and “the well-being of society should be ensured by individual citizens’ own efforts” (7).

In analyzing the results, frequency distributions of responses and positional measures were used to characterize the distribution. Correlation coefficients, such as eta η (for nominal scales) and Spearman’s coefficient rho ρ (for ordinal and interval scales), were also employed to examine relationships between certain variables1.

4. Results

The first aspect to be examined was the general attitudes of respondents toward Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR), including the perceived responsibilities of businesses in this area, the outcomes of CSR practices, and the balance of benefits between the organization and society.

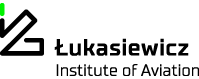

The results (Table 1) show that the young Polish respondents surveyed generally had a positive view of CSR. The vast majority agreed with statements emphasizing the need for corporate social engagement, the benefits it provides, and the positive social perception of companies that implement CSR. The highest level of agreement was observed for statement T1, with 90% of respondents agreeing (most selecting the highest point on the scale – 7). Statements T2 and T3 also received strong agreement, with 81% and 79% of respondents in favor, respectively. For statements T5 and T6, over two-thirds of respondents agreed with them (69% and 67%, respectively).

However, attitudes were more mixed regarding statements that suggested CSR is more focused on achieving business goals than on serving the public interest (T4 and T7). For these statements, responses were more evenly distributed, with 42% of respondents agreeing with each, and a significant portion remaining neutral. These trends are also reflected in the average scores for each statement, with the first group of statements ranging from 5.0 (T6) to 5.89 (T1), while the second group slightly exceeded 4 (T4 – 4.12, T7 – 4.29).

The study also explored potential variations in attitudes based on demographic factors. A modest but noticeable correlation was found between participant gender and expressed attitudes expressed. The overall favorability index toward CSR (calculated as the mean of all responses, with statements T4 and T7 reverse-coded) showed a correlation with gender (η=0.355), with women more likely to express positive attitudes. The strongest gender-related correlations were observed for statements T5, T3, and T1.

No significant correlations were found between attitudes and other demographic characteristics. For income, the absolute value of Spearman’s coefficient ρ only exceeded 0.1 for statements T5 and T6. Regarding respondents’ views on the preferred socio-economic governance model (statism vs. liberalism), the correlation coefficients for statements T1, T5, and T6 did not exceed an absolute value of 0.2 in any case.

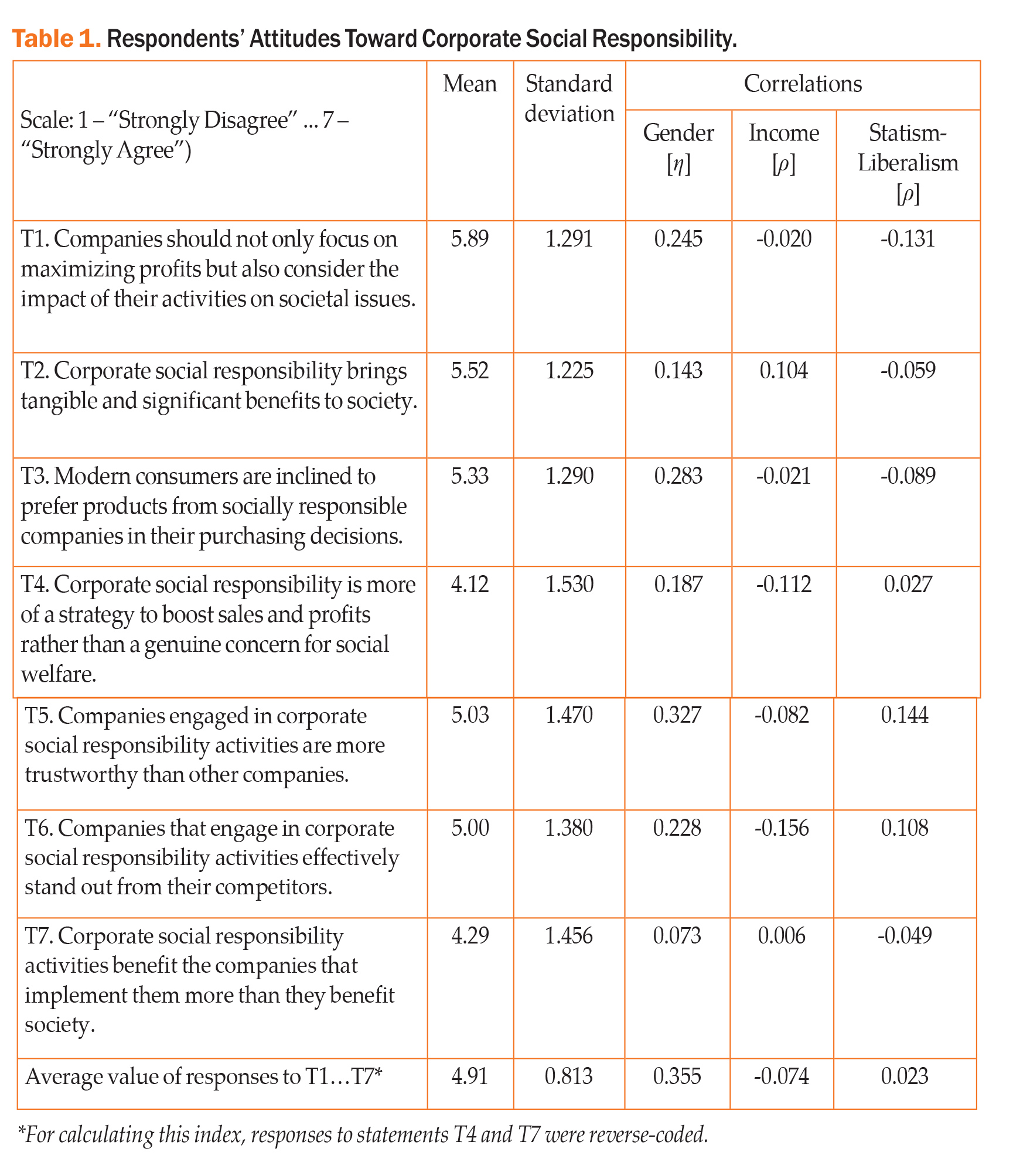

One of the significant outcomes of companies implementing Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) strategies is building trust among stakeholders, including customers. In response to the general statement T5, the majority of respondents agreed with the view that companies practicing CSR are more trustworthy than those that do not.

To gain a more detailed understanding of this phenomenon, the study examined how companies’ activities in various CSR areas contribute to building trust among respondents (Table 2). An overwhelming majority of respondents indicated that a company’s involvement in socially responsible activities did enhance their trust – the percentage of ratings above the neutral position on the scale exceeded 80% in each area, with an average rating above 5. The variation in responses across different CSR areas was minimal; however, the actions of companies in areas directly affecting the respondents – such as fair relations with employees and customers – had a relatively stronger impact on trust (with average ratings in both cases exceeding 6). In contrast, corporate involvement in philanthropic activities had the weakest impact (average rating of 5.37).

The reported influence of CSR activities on trust in a company showed a moderate correlation with the respondents’ gender. For the overall indicator (the mean response to this question), the eta correlation coefficient was 0.255. The strongest correlations were observed in the areas of ecology (Z1, η=0.372) and philanthropy (Z4, η=0.345) – with women consistently indicating higher values on the scale. Similar to the previous question (regarding cognitive attitudes), respondents’ answers did not show a significant correlation with declared income or views on the preferred type of socio-economic order – the rho coefficient values slightly exceeded an absolute value of 0.1 only in the areas of Z1 (for income) and Z5 (for income and views on the preferred socio-economic order).

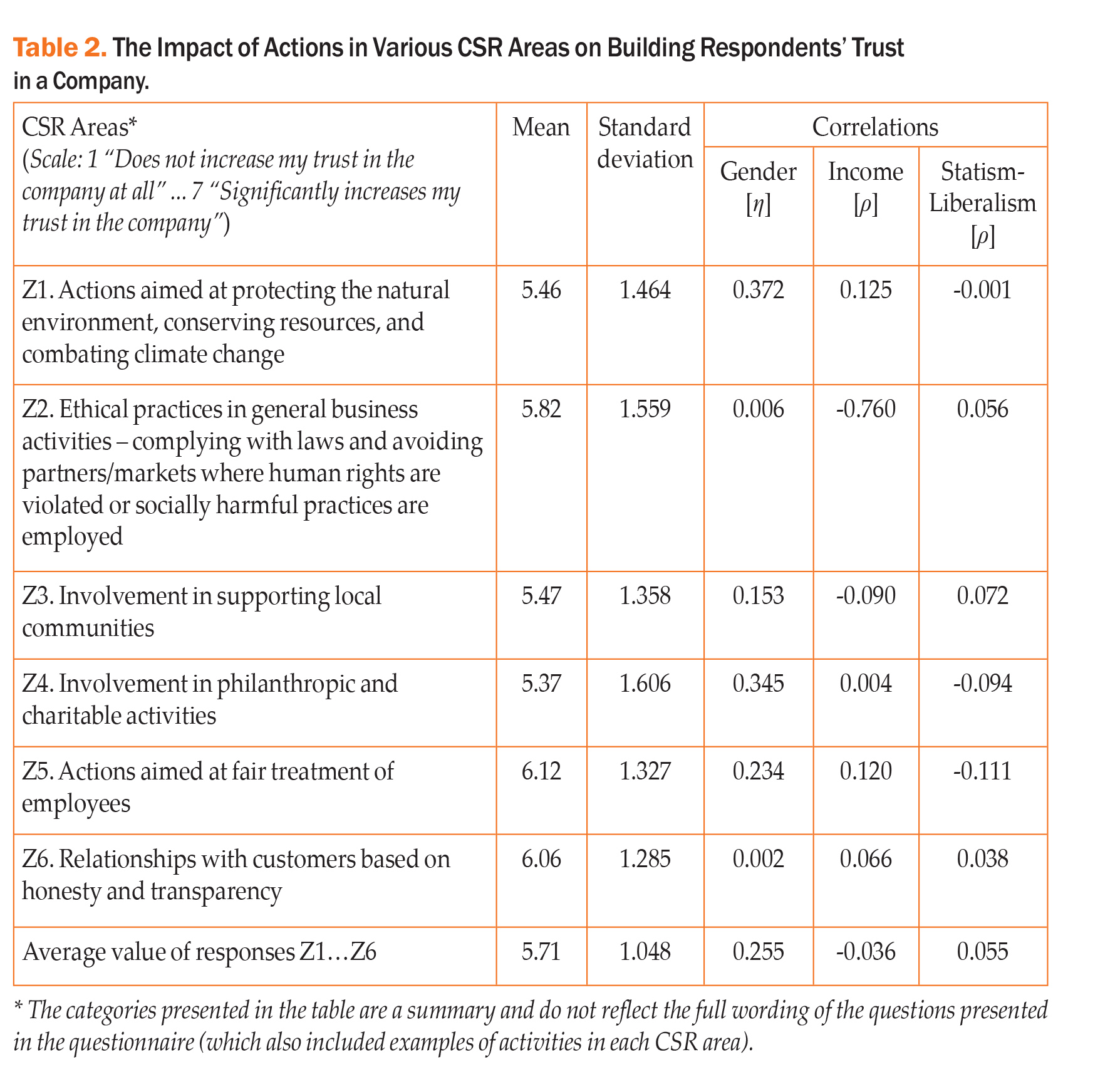

An undoubtedly important aspect of stakeholders’ (including customers’) attitudes towards companies engaging in socially responsible actions is their willingness to support and participate in the pro-social efforts of such companies. In this context, respondents were asked how likely they would be to support a company’s efforts by consciously purchasing its products, recommending them to friends, informing others about the company’s social involvement, or supporting social and charitable activities organized by the company (Table 3).

Similar to the question about building trust, the vast majority of respondents chose responses from the upper part of the scale – though both the percentages and the average scores were slightly lower than in the previous case. The highest level of declared support was noted for actions related to fair relations with customers (W6, 90% of responses above the neutral position, with an average score of 6.02) and employees (W5, with 85% and an average score of 5.75, respectively). The lowest support was recorded for the area of ethical practices in general business activities (W2, with 70% and an average score of 5.09, respectively).

As in the previous question, the overall index of declared support for companies engaging in CSR activities shows only a small correlation with respondents’ gender (η=0.219, with women once again choosing higher positions on the scale). Declarations regarding specific CSR areas showed a more noticeable correlation with gender in the case of ecology (W1, η=0.336) and philanthropic activities (W4, η=0.272). For the area of fair relations with customers (W6), there was also some correlation with respondents’ views on the preferred socio-economic order (ρ=0.274 – support was more frequently declared by proponents of a liberal option, similar to the case of W2, although with a much lower rho value). Regarding respondents’ income levels, rho values exceeding an absolute value of 0.1 were noted only in the areas of W3 and W6.

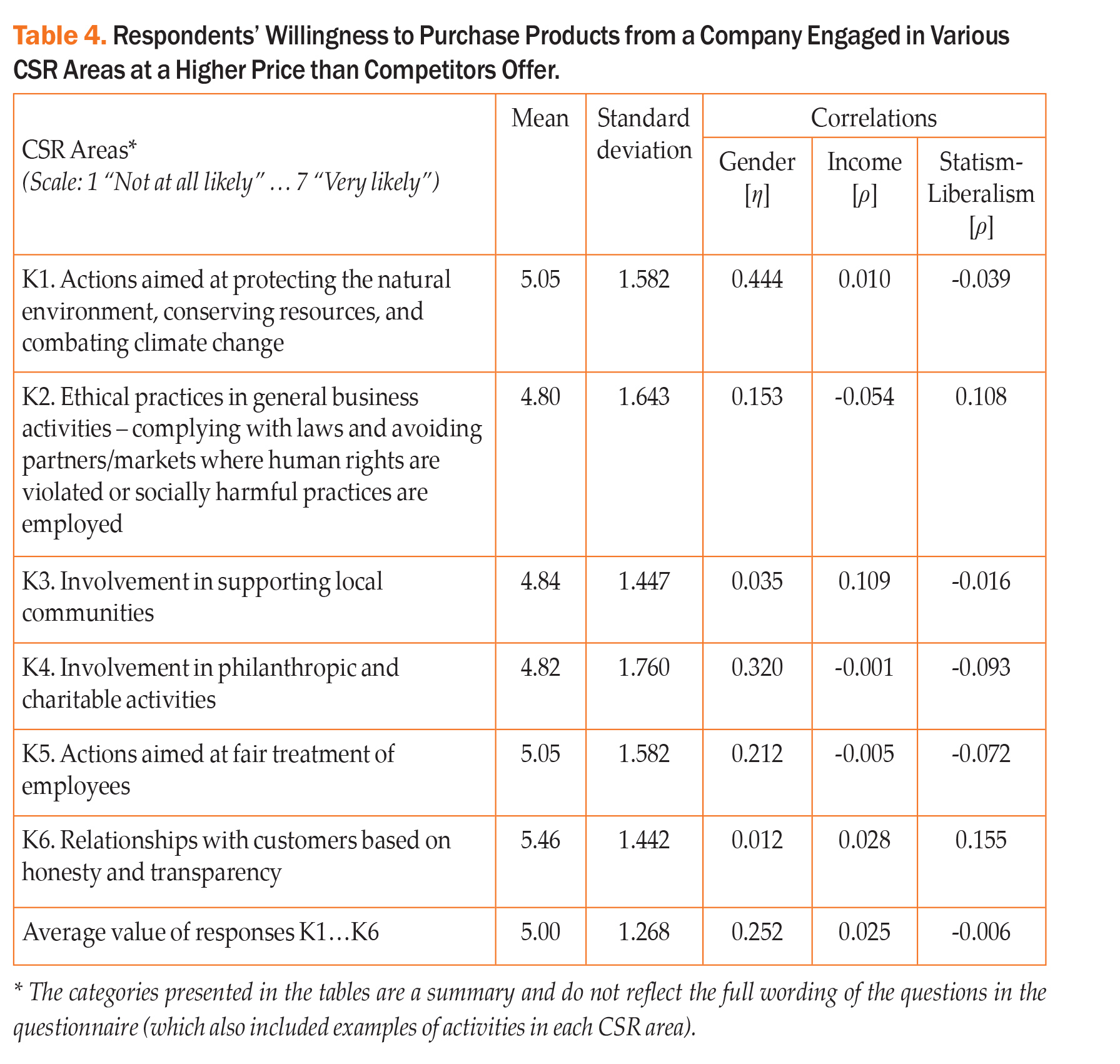

Given that the previous question addressed only general declarations of potential willingness to support a company due to its socially responsible actions (in an abstract sense, without considering the tangible costs of such involvement), we decided to further investigate how this support would manifest when material involvement is required – specifically, the willingness to pay a higher price (compared to competitors) for the company’s products due to its socially responsible actions (Table 4).

Unsurprisingly, in this case, the respondents’ declared willingness to engage is noticeably lower than in the previous, more general question – although a majority still express a willingness to provide material support to companies engaging in each of the indicated CSR areas. The areas of CSR activity that most motivated respondents to offer such support were fair relationships with customers (K6, with 82% of responses above the neutral point on the scale and an average of 5.46). Fair treatment of employees (K5) and environmental actions (K1) also received relatively high scores, with around 70% of responses above the neutral point and an average exceeding 5 in both cases.

The average value of responses across the scales for the various CSR areas, calculated similarly to the previous questions, showed a slight correlation with gender (η=0.252), but no correlation was observed with other analyzed parameters.

Regarding the specific CSR areas, it is noteworthy that there is a significantly higher likelihood reported by women regarding their purchasing of products at a higher price from companies engaged in environmental actions (K1) (η=0.444). In this area, 30% of women chose the highest position on the scale (7), while 27% of men selected the lowest positions (1 or 2). A similar, though slightly less pronounced, trend was observed in the case of corporate philanthropic activities (K4), where 25% of women selected the highest position on the scale, compared to 23% of men who chose the lowest position (η=0.320). The respondents’ answers did not show any significant correlations with other analyzed characteristics, such as income or views on the preferred socio-economic model. Absolute values of the rho coefficient ρ greater than 0.1 were noted only for the areas of K6, K2, and K1, depending on the respondents’ declared socio-economic views, and for K3, depending on respondents’ income levels.

5. Summary

The study clearly revealed a distinctively positive assessment of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) among the surveyed group. Young Polish consumers strongly recognize the general need for corporate social engagement, the benefits it brings, and the positive social perception of companies that implement CSR, while attributing significantly less importance to purely commercial (business) motivations behind such actions2.

The implementation of CSR strategies by companies significantly contributes to building trust in them. The CSR areas that most strongly influence trust among respondents are those that directly benefit the respondents – namely, fair relationships between companies and their customers and employees. In contrast, corporate involvement in philanthropic activities has a relatively smaller impact on trust.

A key aspect of stakeholders’ attitudes toward companies engaging in socially responsible actions is their willingness to support and participate in the pro-social efforts of such companies. In general, most respondents saw it as relatively highly likely that they would support companies that practice CSR by consciously purchasing and recommending their products to friends, informing others about the company’s social involvement, or supporting the company’s social initiatives. Similar to trust-building, the CSR areas most likely to engage respondents in this context are fair relationships with customers and employees. A slightly lower (though still relatively high) level of support was observed when respondents were asked about their willingness to financially “reward” companies for their socially responsible stance by paying a higher price for their products compared to competitors. In this scenario, in addition to the previously mentioned CSR areas (fair relationships with employees and customers), corporate involvement in environmental protection also emerged as a motivating factor for such behavior.

When analyzing the results of the study, it is important to note that women express more favorable attitudes towards the phenomenon of corporate social responsibility, as well as a somewhat stronger influence of the actions taken by companies within CSR on shaping trust and readiness to support socially responsible business activities (with women showing a clearer sensitivity than men, particularly towards actions in the areas of ecology and philanthropy). However, the study did not reveal significant differences in respondents’ attitudes based on other factors such as income or declared views on the preferred socio-economic model.

In summary, the findings from this study underscore a marked positive evaluation of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) among Polish Gen-Z consumers. This demographic places a strong emphasis on the necessity for businesses to engage in social issues, recognizing both the inherent benefits of CSR and the favorable public perception it fosters for companies that implement such practices. Notably, the commercial motivations behind these CSR activities seem to be of lesser importance to them. The areas of CSR that most significantly influence trust among these consumers are those that yield direct benefits – specifically, fair relations with customers and employees. This reflects a broader trend towards ethical consumption among younger consumers in Poland. Moreover, the findings indicate that young Polish consumers are not only aware of CSR but are also prepared to actively support companies that engage in responsible business practices. This willingness extends beyond mere approval; it influences their purchasing decisions, where they show a readiness to pay a premium for products from socially responsible firms. In particular, CSR efforts in environmental protection also emerged as a significant motivator for this demographic. Overall, the study findings indicate that it is crucial for businesses in Poland aiming to succeed in the shifting market landscape to acknowledge and cater to the heightened sensitivity of this young generation towards social and environmental impacts.

Given the limited scope of this empirical study, however, further research involving a larger and more diverse sample is essential to deepen the understanding of CSR perceptions among Gen-Z consumers in Poland (and elsewhere), which is vital for tailoring business strategies that align with their values and expectations.

References

Agyei, J., Sun, S., Penney, E. K., Abrokwah, E., & Ofori-Boafo, R. (2021). Linking CSR and customer engagement: The role of customer-brand identification and customer satisfaction. SAGE Open, 11(3). https://doi.org/10.1177/215824402 11040113

Argandoña, A. (1998). The Stakeholder Theory and the Common Good. Journal of Business Ethics, 17, 1093–1102. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1006075517423

Baran, G. (2021). Społeczna odpowiedzialność w zarządzaniu [Social responsibility in management]. Instytut Spraw Publicznych Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego.

Berens, G., Van Riel, C. B. M., & Van Bruggen, G. H. (2005). Corporate associations and consumer product responses: The moderating role of corporate brand dominance. Journal of Marketing, 69(3), 35-48. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg. 69.3.35.66357

Brown, T. J., & Dacin, P. A. (1997). The company and the product: Corporate associations and consumer product responses. Journal of Marketing, 61(1), 68-84. https://doi.org/10.2307/1252190

Carroll, A. B. (1991). The pyramid of corporate social responsibility: Toward the moral management of organizational stakeholders. Business Horizons, 34, 39-48. https://doi.org/10.1016/0007-6813(91)90005-G

Crane, B. (2020). Revisiting Who, When, and Why Stakeholders Matter: Trust and Stakeholder Connectedness. Business & Society, 59(2), 263–286. https://doi.org/10.1177/00076503187569

Davis, K., & Blomstrom, R. L. (1966). Business and its environment. McGraw-Hill.

Dąbrowska, A., & Janoś-Kresło, M. (2022). Społeczna odpowiedzialność konsumenta w czasie pandemii. Badania międzynarodowe [Social responsibility of consumers during the pandemic. International research]. Oficyna Wydawnicza SGH.

Demkow, K., & Sulich, A. (2017). Wybrane wyzwania związane ze społeczną odpowiedzialnością dużych i średnich podmiotów gospodarczych [Selected challenges associated with the social responsibility of large and medium-sized economic entities]. Marketing i Rynek, 11, 42–52.

Du, S., & Vieira, E. T. (2012). Striving for Legitimacy Through Corporate Social Responsibility: Insights from Oil Companies. Journal of Business Ethics, 110, 413–427. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-012-1490-4

Freeman, R. E., Wicks, A. C., & Parmar, B. (2004). Stakeholder Theory and “The Corporate Objective Revisited”. Organization Science, 15(3), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1040.0066

Friedman, M. (2008). Kapitalizm i wolność [Capitalism and freedom]. Onepress.

Griffin, R. W. (2004). Podstawy zarządzania organizacjami [Fundamentals of organization management]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

Hansen, S. D., Dunford, B. B., Boss, A. D., Boss, R. W., & Angermeier, I. (2011). Corporate Social Responsibility and the Benefits of Employee Trust: A Cross-Disciplinary Perspective. Journal of Business Ethics, 102, 29–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0903-0

He, J. (2018). The Value of Corporate Social Responsibility in the Scope of Triangle Model. American Journal of Industrial and Business Management, 8, 59–68. https://doi.org/10.4236/ajibm.2018.81004

Howaniec, H. (2016). Wpływ społecznej odpowiedzialności biznesu na lojalność konsumentów wobec marki [The impact of corporate social responsibility on brand loyalty among consumers]. Nierówności Społeczne a Wzrost Gospodarczy, 45(1), 32–40. https://doi.org/10.15584/nsawg.2016.1.3

Kazojć, K. (2012). Czarny CSR – nieetyczne wykorzystanie koncepcji przez organizacje [Black CSR – unethical use of the concept by organizations]. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Studia i Prace Wydziału Nauk Ekonomicznych i Zarządzania, 30, 35–48.

Lee, Y. J., Haley, E., & Yang, K. (2013). The mediating role of attitude towards values advocacy ads in evaluating issue support behaviour and purchase intention. International Journal of Advertising, 32(2), 233–253. https://doi.org/10.2501/IJA-32-2-233-253

Leoński, W. (2015). Wpływ CSR na wyniki finansowe przedsiębiorstw [The impact of CSR on corporate financial performance]. Zeszyty Naukowe Uniwersytetu Szczecińskiego. Finanse, Rynki Finansowe, Ubezpieczenia, 74(2), 135–142.

L’Etang, J. (1994). Public relations and corporate social responsibility: Some issues arising. Journal of Business Ethics, 13, 111–123. https://doi.org/10.1007/ BF00881580

Lozano, R., Carpenter, A., & Huisingh, D. (2014). A Review of ‘Theories of the Firm’ and their Contributions to Corporate Sustainability. Journal of Cleaner Production, 106, 430–442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2014.05.007

Luo, X., & Bhattacharya, C. B. (2006). Corporate social responsibility, customer satisfaction, and market value. Journal of Marketing, 70(4), 1–18. https://doi.org/ 10.1509/jmkg.70.4.00

OECD (2023). OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises on Responsible Business Conduct. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/81f92357-en

PKN (2012). Polska Norma PN-ISO 26000:2012 Wytyczne dotyczące społecznej odpowiedzialności [Polish Standard PN-ISO 26000:2012 Guidelines on social responsibility]. Polski Komitet Normalizacyjny. https://www.pkn.pl/sites/ default/files/sites/default/files/imce/files/discovering_iso_26000.pdf

Schwartz, M. S., & Carroll, A. (2003). Corporate Social Responsibility: A Three-Domain Approach. Business Ethics, 13, 503–530. https://doi.org/10.2307/3857969

SGH. (2022). Odpowiedzialny konsument i przedsiębiorstwo (Raport z badań Instytutu Zarządzania Szkoły Głównej Handlowej w Warszawie). https://odpowiedzialnybiznes.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/RAPORT-BAROMETR_2022.pdf

Socorro-Márquez, F. O., Danvila-Del Valle, I., Serradell-López, E., & Reyes Ortiz, G. E. (2023). Collective Social Responsibility: An extended three-dimensional model of Corporate Social Responsibility for contemporary society. CIRIEC – España, Revista de Economía Pública, Social y Cooperativa, 107, 259–288. https://doi.org/10.7203/CIRIEC-E.107.20611

Wołoszyn, J., Stawicka, E., & Ratajczak, M. (2012). Społeczna odpowiedzialność małych i średnich przedsiębiorstw agrobiznesu z obszarów wiejskich [Social responsibility of small and medium-sized agribusiness enterprises from rural areas]. SGGW.

Zakusilo, A. (2021). Studenci Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego pokolenia Z jako członkowie społeczeństwa obywatelskiego [Generation Z students of the Jagiellonian University as members of civil society]. Fabrica Societatis, 4, 160–184. https://doi.org/10.34616/142705

Mirosław Pacut – Assistant Professor at the Department of Marketing at the University of Economics in Katowice. His scientific and research specializations include topics related to marketing communication (particularly in a virtual environment), consumer market behaviors, the marketing of non-profit organizations, and the marketing of retail enterprises and e-commerce. He has authored research publications in the fields of marketing and management.