- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Selected aspects of innovative activity of polish enterprises in 2016–2020

Agnieszka Bobola1, Irena Ozimek2, Iwona Pomianek2, Joanna Rakowska2

1Department of Tourism, Social Communication and Counselling, Institute of Economics and Finance, Warsaw University

of Life Sciences, ul. Nowoursynowska 166, 02-787 Warszawa, Poland

2Department of Development Policy and Marketing, Institute of Economics and Finance, Warsaw University of Life Sciences,

ul. Nowoursynowska 166, 02-787 Warszawa, Poland

*E-mail: irena_ozimek@sggw.edu.pl

Agnieszka Bobola; ORCID: 0000-0002-7441-6055

Irena Ozimek; ORCID: 0000-0003-3430-8276

Iwona Pomianek; ORCID: 0000-0002-2858-2714

Joanna Rakowska; ORCID: 0000-0001-5135-6996

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0017

Abstract:

The study aimed to analyse selected aspects of innovative activities of enterprises in Poland in 2016–2020. The article is based on literature studies, using a query of scientific publications and statistical analyses of data published by Statistics Poland and the Patent Office of the Republic of Poland (PORP) for 2016–2020. Findings show that in 2016–2020 the number of innovative industrial and service enterprises that primarily implemented innovations in business processes was increasing. The innovations included, in particular, processes of manufacturing products in industrial enterprises, as well as external and internal communication in service enterprises. Although the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic did not affect the activities of the majority of surveyed companies significantly, the changes in the functioning of those impacted by COVID-19 caused a more frequent implementation of innovations in business processes than in the product processes. Innovative activities conducted in enterprises were financed mainly from own funds, including internal outlays for innovative activities of enterprises and funds obtained from government and local government institutions, most often used by the entrepreneurs to purchase fixed assets. The smallest share of outlays was allocated to the protection of intellectual property in enterprises, which is undoubtedly one of the most often underestimated areas determining effective protection of innovations in enterprises.

MINIB, 2022, Vol. 45, Issue 3

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2022-0017

P. 71-96

Published 30 September 2022

Selected aspects of innovative activity of polish enterprises in 2016–2020

Introduction

Entrepreneurs running a business strive to achieve success, and the basic measure of their success is not only their remaining on the market but, most of all, achieving a positive financial result of their business activity. In order to enable entrepreneurs to make a profit, the products and services offered by them should have characteristics that consumers perceive as desirable and satisfactory to them. It is connected with the necessity of recognising the needs, preferences and awareness of consumers as precisely as possible, while at the same time searching for innovative

solutions that allow entrepreneurs to stay ahead of competitors (Zimon & Gawron-Zimon, 2014). Additionally, it should be remembered that entrepreneurs striving to modernise their offer should take care of closer relations with clients who have new ideas and willingly share their observations, treating it as a source of innovation and development (Dobiegała-Korona, 2012, p. 68).

Pérez-Luno, Valle Cabrer and Wiklund (2007, p. 80) indicate that of the two possible paths-imitation and innovation-only the latter leads to a competitive advantage in the market. In turn, according to Dereli (2015, p. 1367), in order to survive in a competitive market, companies must carefully follow and implement innovations or must be innovative themselves. Only enterprises that offer innovations can achieve a competitive advantage (Adegbesan, 2009; Dereli, 2015, p. 1367; AnningDorson, 2018, p. 580). Grzegorczyk (2011, p. 26) emphasises that the possibility of achieving a competitive advantage is closely related to the competitive situation on the market and the company’s resources, especially with its product offer. An entrepreneur creates an opportunity to obtain the opinion of an innovator and achieve a dominant position on the market by introducing a new or significantly improved product to the market. It should be highlighted, that how long this dominance in the market will last largely depends on the behaviour of competitors and their innovative activities. Friar (1995, p. 33) notes that the product innovation alone may not be enough to keep a company in a dominant position. The success in the field of product innovation decreases with the increase of the intensity of market competition. This may result from the inability of customers to distinguish products based on, for example, their functional performance.

Therefore, in order to keep pace with the competition, it is necessary to constantly implement not only product innovations, but also non-product innovations and appropriate innovation management (Friar, 1995; Dereli, 2015, p. 1369), which allows the enterprise to choose the appropriate protection method for the innovative solutions being developed or implemented in the enterprise.

The article primarily aimed to present selected aspects of the innovative activity of Polish enterprises. To achieve it, we attempted to answer the following research questions:

1. What is the share of enterprises implementing innovations in the total number of enterprises? Do the profile and size of the enterprise affect their innovative activities?

2. Did the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 have a positive impact on innovative activities in Polish enterprises?

3. What are the sources of finances for innovative activities in Polish enterprises?

4. What kind of innovations do entrepreneurs finance from outlays on innovative activities?

5. How do entrepreneurs protect innovative solutions?

Materials and Method

The study is based on a critical literature review, which is based on a query of selected scientific publications on innovation and innovativeness as a source of competitive advantage in enterprises, as well as statistical analyses of secondary data, including structure and chain index.

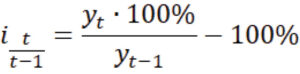

To calculate the chain index, a modified formula was used (Major & Niezgoda, 2003, pp. 96–97), in which 100% was subtracted for easier interpretation of the obtained results:

where: i represents dynamics, t the current year, t–1 the previous year, yt the value in the current year and yt–1 the value in the previous year.

We analysed data published by Statistics Poland (previously: the Central Statistical Office of Poland) and the Patent Office of the Republic of Poland (PORP) for 2016–2020. The indicators of the structure made it possible to observe the changes that took place in the analysed period, while the chain index analysis made it possible to determine the intensity of changes that took place over the observed years.

Analyses presented in this article cover small enterprises (employing 10–49 people), medium-sized enterprises (employing 50–249 people) and large enterprises (employing ≥250 people), because Statistics Poland collects and publishes data on innovations based on the Oslo Manual 2018 methodology only within these groups of enterprises.

Innovations in the Enterprise

The term ‘innovation’ can be understood in many ways, but there is no doubt that it derives from the Latin word ‘innovatio’, meaning renewal or ‘innovare’, indicating renewal, refreshing, changing (Kopaliński, 2006). The literature includes numerous, very different approaches to defining the essence of innovation, as well as its terminological interpretation or functions (Montoya-Weiss & Calantone, 1994; Drucker 1998). It results in the lack of a single definition of innovation in economics and management (Table 1).

In the short review of definitions of innovation presented above, we can see both a narrow (i.e. the first introduction of a solution in the world) and a broad (i.e. the first use of a solution in a specific enterprise) understanding of innovation. Most often, however, they are equated with a novelty, a change, and refer to new products or new technologies (Sikora & Uziębło, 2013, p. 351). However, attention should be paid to the fact that these definitions usually contain some regular elements determining the essence of innovation and defining its character. They include: subject (enterprise, human), object (technology, organisation, market), novelty (originality), economics or positive evaluation of changes and the fact of their implementation, assimilation (Kamiński, 2018).

The large diversity of definitions resulted in the introduction of many different types of classifications to the theory, allowing

researchers to divide innovations by the subject, the effects, the originality of changes or the nature of innovations and their

significance in terms of changes for the commercial sector (Sławińska, 2015).

Until 2018 the division of innovation according to the subject indicating its technological (product and process innovation) or non-technological nature (organisational and marketing innovations) (Oslo Manual, 2005) was the most basic and most frequently used classification. It was replaced by product innovations and business process innovations after publication of the new Oslo Manual (2018). The new definitions specify more precisely what conditions must be met to consider a product, a service or a process to be an innovation. It is indicated that the innovations must significantly differ from the products or services already existing on the market or they must significantly differ from the company’s business processes already used by the enterprise.

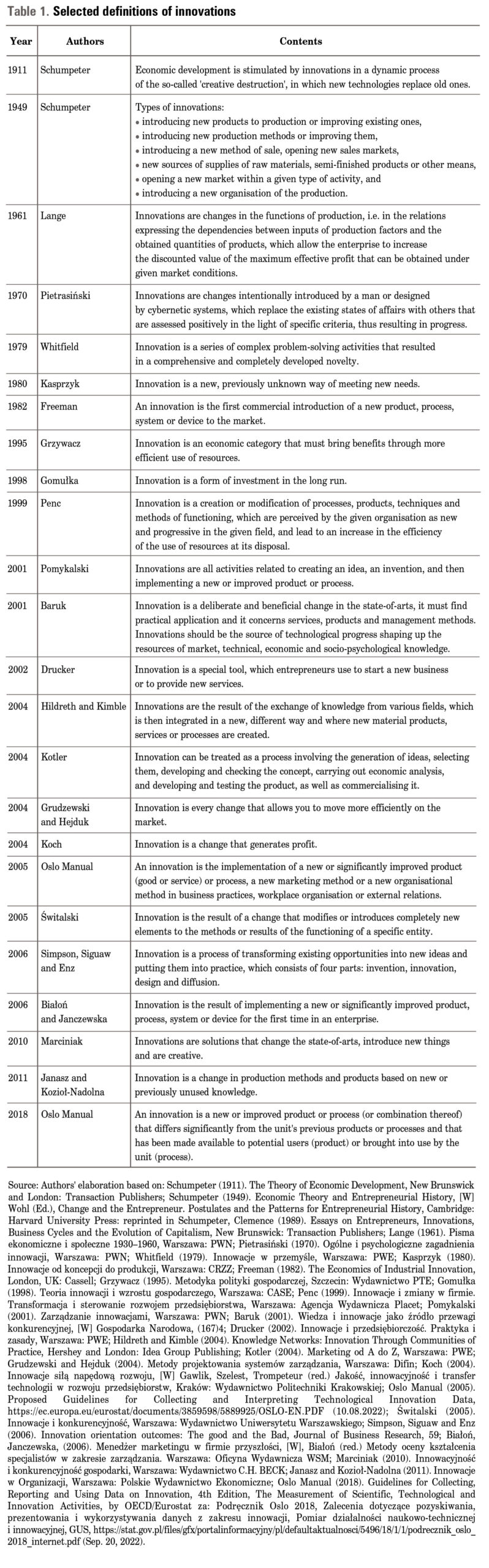

Analysing the data of Statistics Poland (Table 2) for 2016–2018, it can be noticed that the share of enterprises implementing innovations in the total number of enterprises, both industrial and service ones, was systematically increasing. After this period, a temporary decrease in the share of enterprises implementing innovations was observed in 2019, and in 2020 the innovative activity of enterprises in Poland increased again. It is worth noting that in 2020 the indicators of the share of innovative enterprises in the total number of enterprises were the highest and amounted to 31.4% in the case of industrial enterprises and 30.8% in the case of service enterprises.

Over the analysed time the largest number of innovations in both industrial and service enterprises resulted from the implementation of innovations in business processes. The share of innovative industrial enterprises increased from 15.2% in 2016 to 26.3% in 2020 and the share of innovative service enterprises increased from 10.4% in 2016 to 39% in 2020.

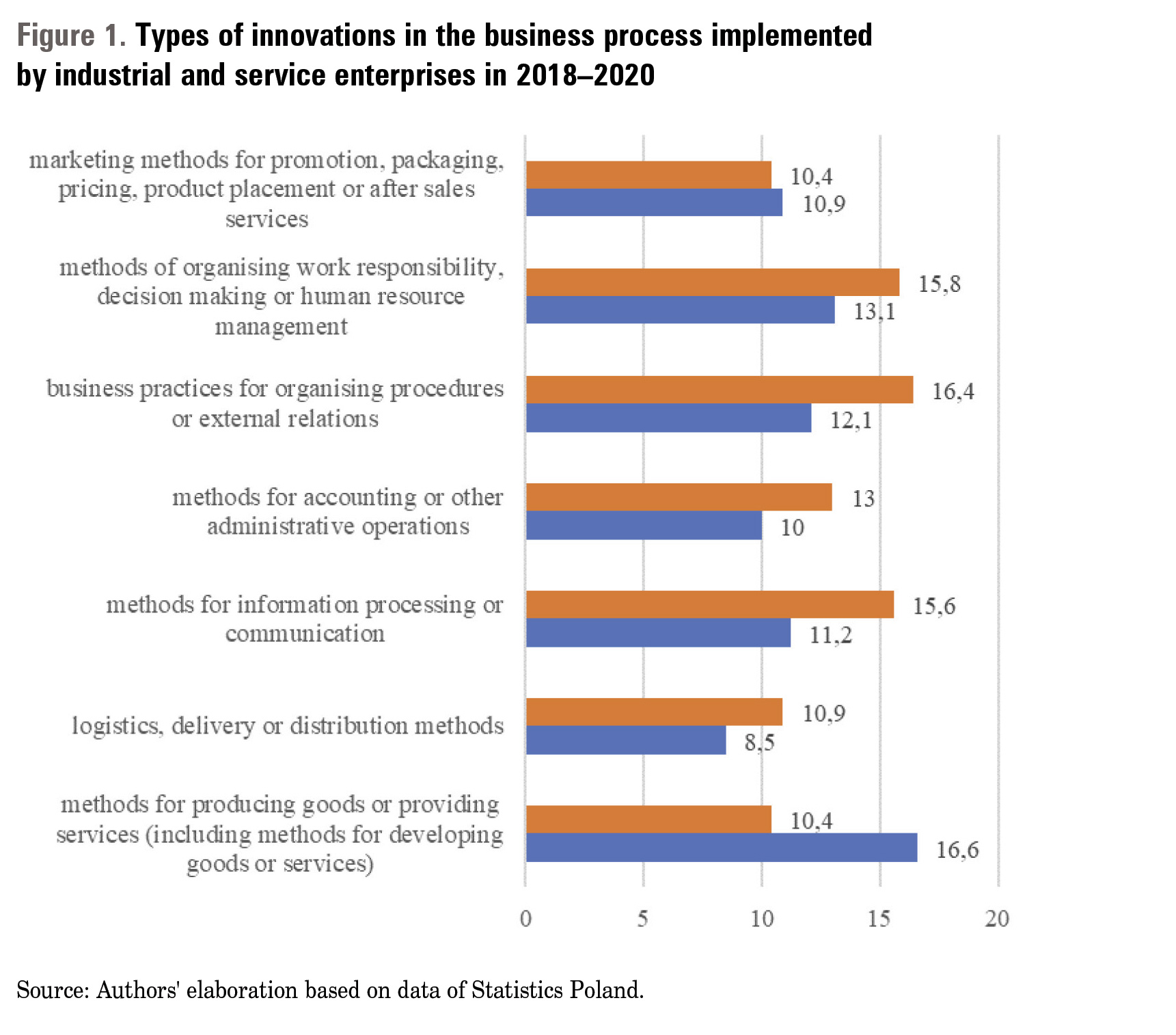

In 2018–2020 (Figure 1), industrial enterprises innovating business processes most often implemented new methods of manufacturing products or providing services (including the development of new products or services), assigning tasks and managing decision-making powers (including their effective delegation) and human resources, and changed principles of operation extant within the company and/or those governing the entity’s external relations. In turn, service enterprises changed mainly the rules of operation extant within the company and/or those governing the entity’s external relations, as well as the rules laying down the modus operandi for the assignment of tasks, management of decision-making powers (including their effective delegation) and human resources, and development and implementation of solutions for information-processing and communication requirements.

When analysing the data on product innovations in 2016–2020 (Table 2), it should be noted that the share of enterprises implementing them was much lower than that of enterprises implementing innovations in the business process. However, the growing share of enterprises implementing product innovations in the total number of enterprises should be assessed positively (in the case of industrial enterprises, the share of enterprises implementing innovations increased from 12.4% in 2016 to 18.4% in 2020, while in the case of service enterprises the share almost doubled: from 6.9% in 2016 to 12.1% in 2020). It may indicate the introduction of newer or significantly improved products that can meet the expectations of the contemporary consumer.

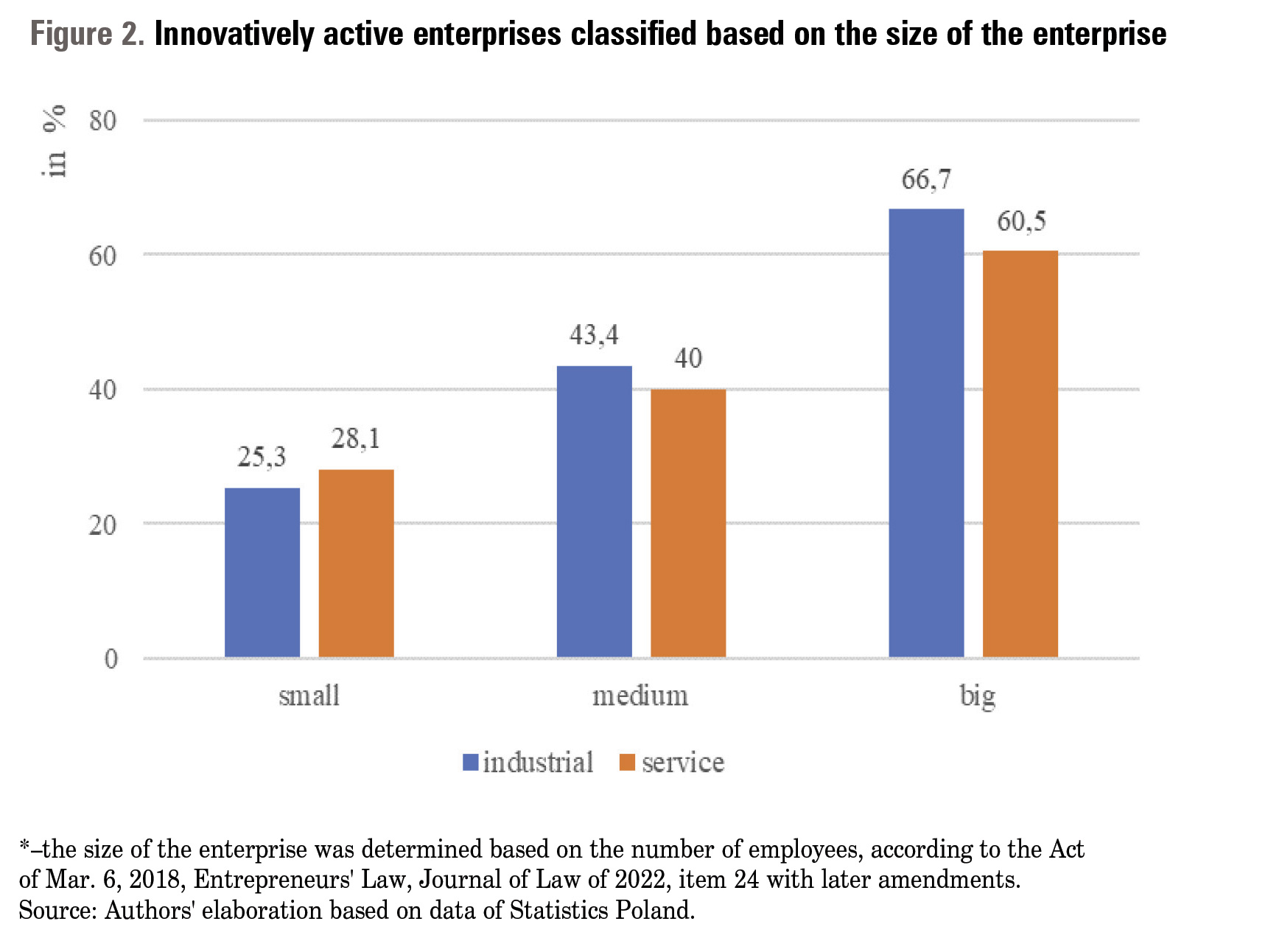

The data from Statistics Poland also show that large enterprises were most innovative in 2020 (they constituted 66.7% in the case of industrial enterprises and 60.5% in service enterprises). It might have resulted from the need to ensure the sufficient outlays financing innovative activities of enterprises, which large enterprises planned and included in the long-term development of their organisations (Figure 2).

Impact of COVID-19 on Innovative Activities of Enterprises

The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 changed the rules of functioning of enterprises all over the world. In Poland, a number of restrictions were introduced (Ministry of Health Regulation, 2020), which forced entrepreneurs to take measures to adapt their businesses to the new situation.

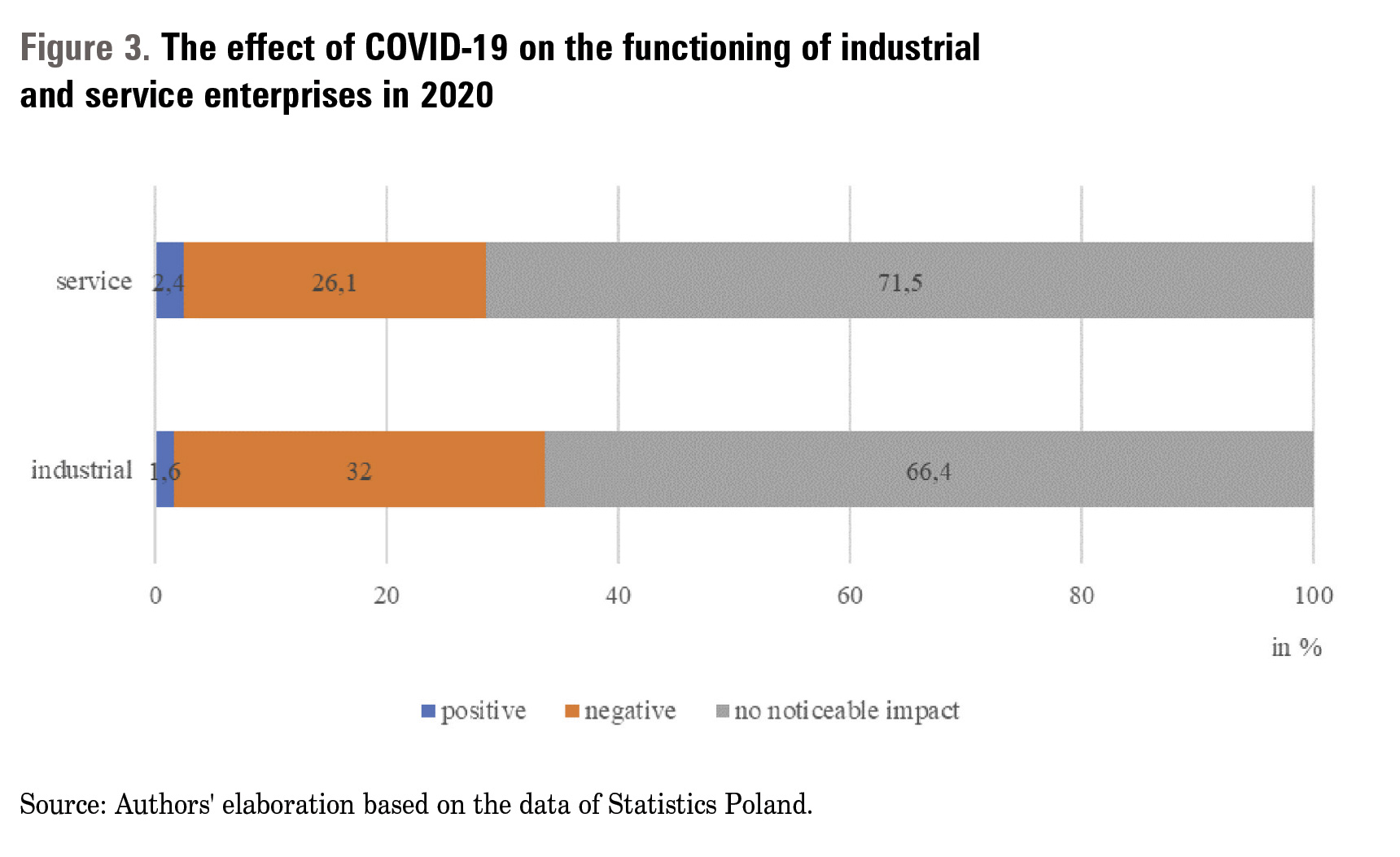

Results of the survey carried out by Statistics Poland indicate no noticeable impact of the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic (Figure 3) on the functioning of enterprises. Such effect was declared by over 66% of industrial enterprises and over 71% of service enterprises. On the other hand, almost a third of industrial companies and 26% of service companies believed that the outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic had a negative impact on the company’s operations. Positive influence of COVID-19 was recorded in 1.6% of industrial enterprises and 2.4% of service enterprises.

Due to the situation related to COVID-19, in 2020, 10.6% of industrial enterprises implemented new or significantly changed products, whereas 18.2% implemented new or significantly changed business processes (Figure 4).

Among service enterprises that, in 2020, implemented changes in their functioning forced by the situation related to COVID-19, 9.2% introduced new or significantly improved products, whereas 37.0% introduced new or significantly changed business processes.

Types of Support for Innovative Enterprises

Hu, Yu, Jin, Pray and Deng (2022, p. 709) note that governments use some incentives to make enterprises create and develop innovation. These incentives include, among others, specific funds for enterprise innovation, promotion of cooperation between the enterprise sector and public research sectors and institutes, strengthening protection of intellectual property rights, reforms of state-owned enterprises and establishing research and development institutes.

In Poland, support for innovative entrepreneurs may take the form of (i.e. Journal of Laws of 2021, item 706, as amended):

(1) granting a technological loan by commercial banks and a technological premium by Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego;

(2) granting the entrepreneur the status of a research and development centre;

(3) aid granted under programmes in the field of innovation of the economy, established by the minister competent for the economy.

This act also explains the terms ‘investment activity’ and ‘technological investment’. Innovative activity is ‘the development of a new technology and launching on its basis the production of new or significantly improved goods, processes or services’ (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 706, as amended). A technological investment, on the other hand, means:

(a) purchase of a new technology, its implementation and launching on its basis the production of new or significantly improved products, processes or services and providing conditions for the production of these products, processes or services, or

(b) implementation of own new technology and launching on its basis the production of new or significantly improved products and providing conditions for the production of these products, processes or services.

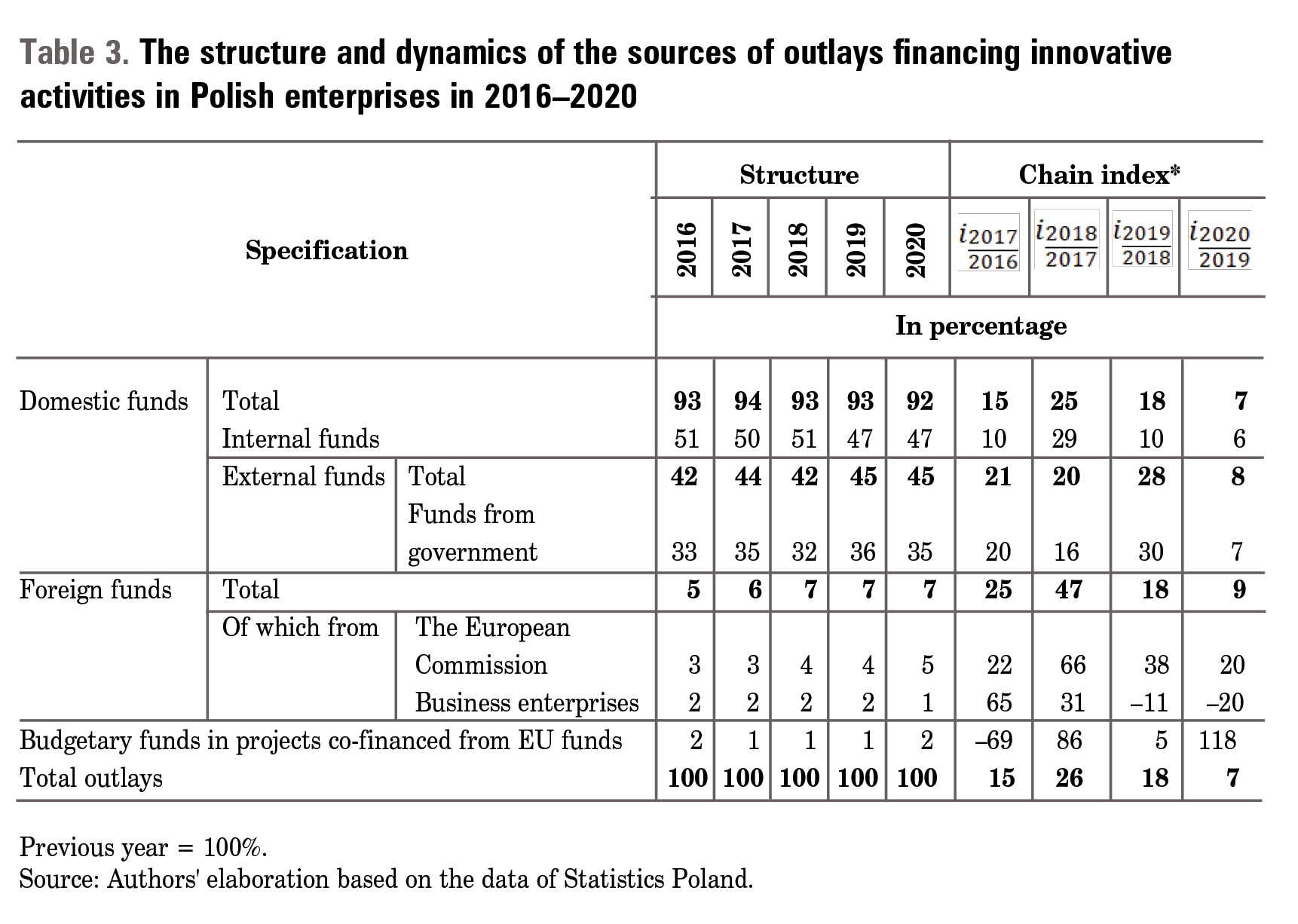

When analysing the sources of outlays financing innovative activities in Polish enterprises, it should be noted that the vast majority of them are financed from domestic funds (in the structure of the distribution of outlays, their value in the analysed years was around 90%). This situation was caused by the distribution of public aid for the development of innovation from the internal funds of enterprises, as well as from those of government institutions and local governments. In 2016–2020, the annual value of outlays on innovative activities from this source (Table 3) remained at the level of around 35%.

In 2016, the total value of outlays was over PLAN 19 billion, and in 2020 it increased to a level exceeding PLN 35 billion. It resulted in an increase in the value of outlays from both domestic and foreign funds and budget funds co-financed from the EU funds. Findings on the dynamics of changes in the value of outlays on innovative activities show a large increase in outlays between 2017 and 2018. It may indirectly be related to the introduction of the 2016 amendment to the R&D tax relief into the Polish tax system, which replaced the technology relief. From 2018, this relief allowed entities that do not have the status of a research and development centre to deduct 100% of eligible costs, and in the case of research and development centres, even 150% of eligible costs (except for the costs of patents, protection rights for utility models, and rights from registration of industrial designs incurred by research and development centres being large entrepreneurs; for these entities, these costs could be deducted up to 100%) (Goyke, 2018, p. 31).

It should also be noted that in 2018–2020, only 6.2% of Polish enterprises (3.7% industrial and 2.5% service) benefitted from the R&D relief, and only 7% of enterprises (4.2% of industrial and 2.8% of services) benefitted from the reliefs or incentives for other operating activities (GUS, 2021).

The Use of Funds for Innovative Activity

The implementation of innovative activities in enterprises is closely related to research and development (R&D), which, as Wiśniewska aptly notes (2017, p. 308), covers both basic research and applied research, as well as development works. The author also emphasises that the above-mentioned activities constitute one of the main conditions for innovation.

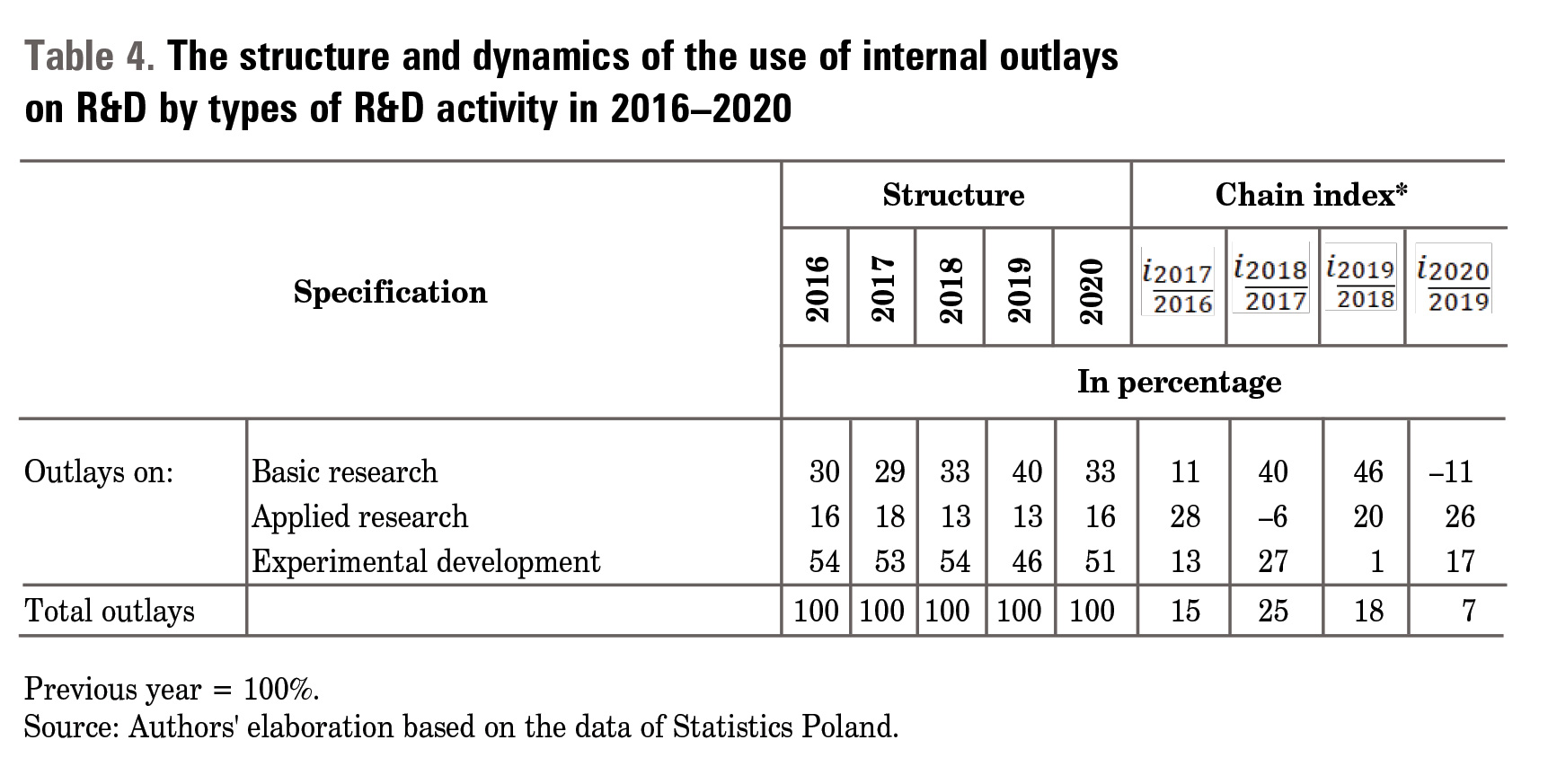

Taking into account the dominant share of internal outlays financing innovative activities in Polish enterprises in 2016–2020. Table 4 presents the use of these funds. In the analysed period, the value of total internal outlays on R&D increased from PLN 9.6 billion in 2016 to PLN 16.5 billion in 2020, which was influenced by the increase in the value of outlays in the subsequent years of the analysed period.

It is worth noting that the largest share of internal outlays was allocated by entrepreneurs to the implementation of development works (approx. 50%) and basic research (approx. 33%). Taking into account the dynamics of changes in the use of internal outlays, the highest increase in the value of funds allocated to the financing of basic research was observed between 2019 and 2018, in the case of applied research between 2017 and 2016; and when analysing the data on financing development works, the largest increase in funds was between 2018 and 2017.

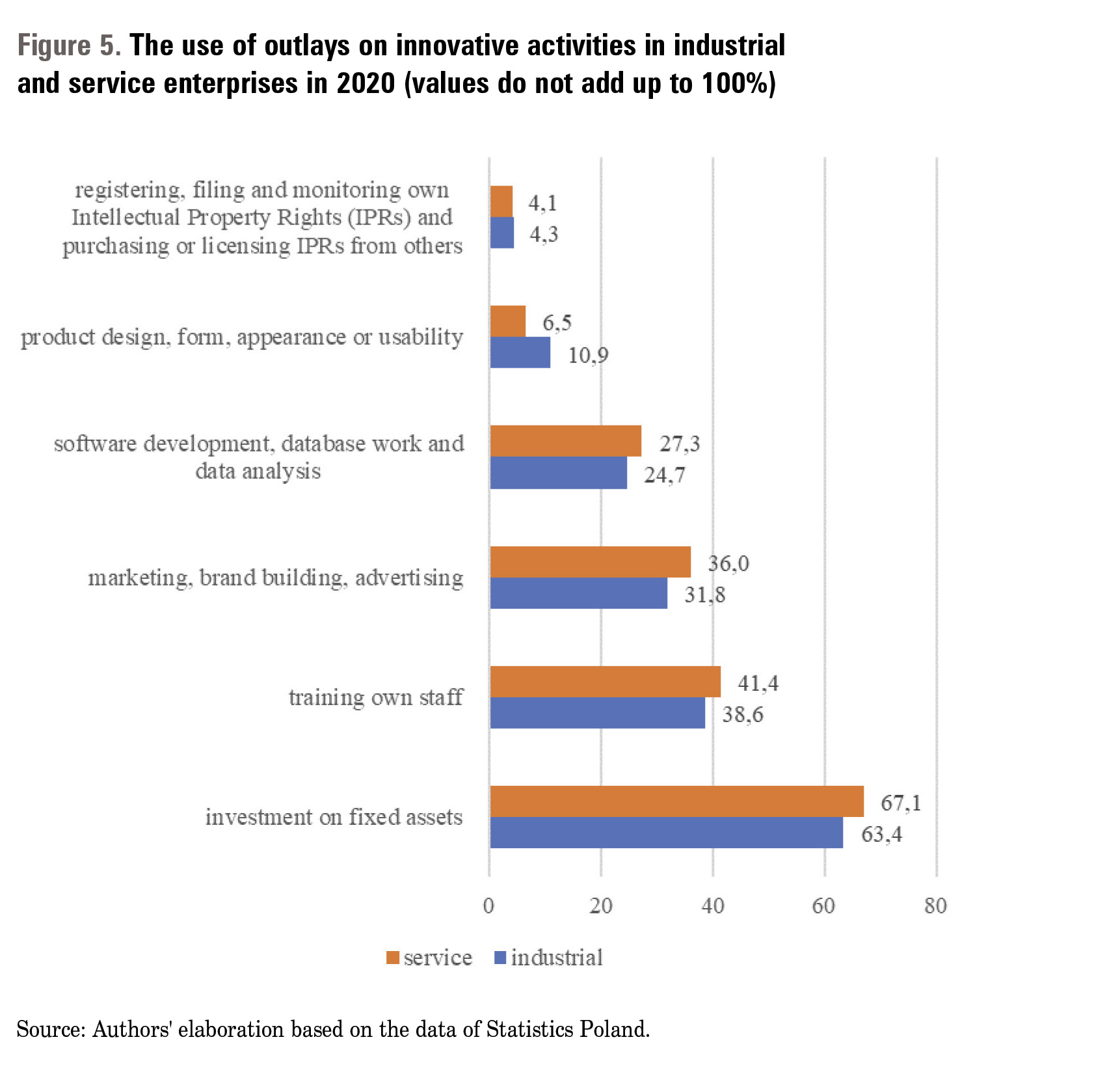

By the outlays on innovative activities in 2020 (Figure 5), entrepreneurs of the industrial and service sector most often financed purchases of fixed assets (63.4% and 67.1% of all innovation-active enterprises, respectively) and employee training (38.6% and 41.4% of all innovation-active enterprises, respectively), and invested in building the brand and marketing activities (31.8% and 36% of all innovation-active enterprises, respectively).

The lowest value of outlays was spent by entrepreneurs representing both industrial and service enterprises on the acquisition or obtaining of intellectual property rights from other entities and registration of their own intellectual property rights (4.3% and 4.1% of the total number of innovatively active enterprises, respectively).

Protection of Innovations in Enterprises

Inventions, utility and industrial models, trademarks, topographic signs or topographies of integrated circuits, and works as well as knowhow may be created as a result of the innovative involvement of enterprises. It should therefore be remembered that entrepreneurs may use various types of protection, which in the case of a single item may indicate the need to choose from among the provisions on combating unfair competition, including trade confidentiality (Journal of Laws of 2022, item 1233), industrial property rights (Journal of Laws of 2021, item 324) or copyright (i.e. Journal of Laws of 2021, item 1062, as amended).

J. Schumpeter (p. 19) clearly separated the meaning of the term ‘innovation’ from the term ‘invention’. In practice, many inventions never become innovations because they are not put into production, and not all innovations meet the conditions of patentability to be classified as inventions. In addition, Schumpeter focussed only on technical innovations and their importance in achieving positive economic effects.

From the point of view of products and services created in enterprises, the most important thing is the appropriate management of innovations, enabling, inter alia, the selection of appropriate protection for upcoming innovations.

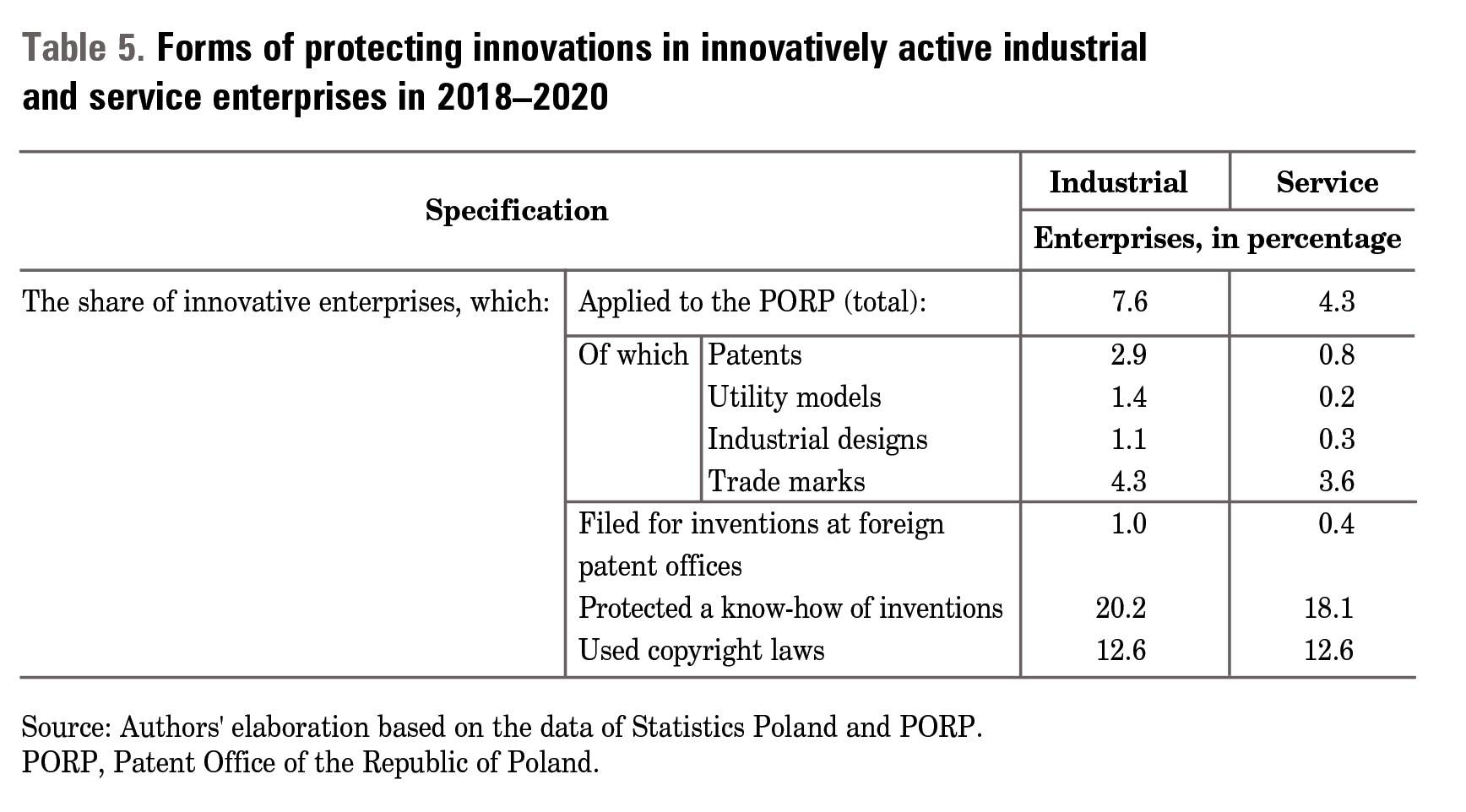

The data of Statistics Poland and the PORP for 2018–2020 show that entrepreneurs running a business in Poland, both in the industrial and service sectors, most often chose business confidentiality as a form of protection for innovative solutions (20.2% in the case of industrial enterprises and 18.1% of service enterprises). Copyright protection was chosen by 12.6% of industrial enterprises and the same share of service enterprises (Table 5).

The least innovative enterprises decided to be protected in the form of industrial property rights by submitting their innovative solutions for protection to the PORP or another entity granting a wider scope of territorial protection, i.e. the European Patent Office (EPO), the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO) or the European Union Intellectual Property Office (EUIPO).

It should be noted, that a large group of both industrial and service enterprises engaged in innovative activities decided to protect their trademarks (4.3% of industrial enterprises and 3.6% of service enterprises) and inventions (2.9% of industrial and 0.8% of service enterprises).

It is worth emphasising that resources or competences difficult to imitate are the basis of the company’s competitive advantage (Grzegorczyk, 2020, pp. 198–199). Preventing imitation is, in turn, a fundamental role of intellectual property rights (World Intellectual Property Office; O’Donoghue, Scotchmer, & Thisse 1998; Maurer & Scotchmer, 2002; Anton & Yao, 2004; Granstrand, 2006; Mokyr, 2009; Holgersson, 2013; Muça, Pomianek, & Peneva, 2022). These rights give a sense of security and certainty to innovators, inventors and entrepreneurs. Their time, financial outlays and knowhow used to develop a new solution will have a chance to pay for themselves (Saha & Bhattacharya, 2011, p. 88), as long as the law will remain in force.

A patent granted for an invention (in Poland-for a maximum of 20 years counted from the date of submitting the application to the PORP) is not limited in its purpose to obtaining a document authorising the exclusive use of the patent by the inventor (entrepreneur), e.g. for manufacturing a unique product using modern technology and thus competing effectively in the market. A patent is a component of the company’s assets, increasing its market value. It also improves the image of the company-as innovative, profitable and with development prospects-in the eyes of investors and contractors. It should be emphasised that the novelty of the invention is tested on a global scale, and thus even if the patent is valid in a limited area-e.g. a national patent in a given country in which an application was made for protection, or a European patent in states that are parties to the European Patent Convention of 1973 (The European Patent Convention, 17th edition 2020) — this is still a clear signal for competitors and business partners that the company was the first to apply this innovative technical solution on a global scale. As Czub (2021, p. 197) notes, the invention consists in using matter in a new way to satisfy various human needs (individual or collective), and the speciality of the innovator’s contribution is that the presence of such needs might have been reported by society not long before the invention is made or created for the first time by the innovator developing the invention, thus making the invention a particularly timely contribution. Especially, the latter situation gives the entrepreneur a chance to gain a competitive advantage-and even, to some extent, a monopoly on the market (Long, 1991, p. 846). As Wiśniewska rightly points out (2017, p. 316), patent protection does not guarantee its successful commercialisation, but resignation from such protection may deprive the entity of the possibility of benefitting from this right. The protection of intellectual property is also intended to promote fair competition (Al-Aali & Teece, 2013, p. 17; Komor, 2022, p. 13). As

emphasised by Sojkin (2012, p. 132), it should also be remembered that one of the key issues in the process of commercialisation of innovations is the assessment of the impact of innovation on the existing product portfolio, in particular the risk of ‘cannibalism’ within the portfolio. Financial opportunities that guarantee the implementation of the tasks provided for in the adopted strategy for introducing a new product to the market are an important element of commercialisation. This is especially important when it is necessary to make a decision to introduce innovation in an investment.

Conclusions

The role of innovation is extremely important in the process of social and economic development and progress, because innovation is an inherent condition for the development of not only enterprises but also the entire economy (Firlej, 2012). Innovations are combined with innovativeness, where the latter is understood as a tendency to create new or improve existing products, technological processes and systems of organisation, management or marketing, whose outcome is typically expected to be creative changes that lead to the emergence of new solutions in enterprises and adaptation of external scientific and technical achievements to the needs of the enterprise.

Based on the literature review and analyses of secondary data provided by Statistics Poland (GUS) and the PORP for 2016–2020, the following conclusions can be drawn:

1. The share of innovatively active industrial and service enterprises in Poland is growing systematically. In 2020, in both groups of enterprises, approximately one-third of small-sized, 40% of medium-sized and 60% of large enterprises introduced innovations.

2. A high frequency of implementation of innovations in business processes was observed in both industrial and service enterprises. Industrial companies implemented mainly changes in the processes of manufacturing products, while service companies changed the methods of internal and external communication.

3. The majority of entrepreneurs did not feel a significant impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on their operations in 2020, while nearly one-third described this impact as negative, and only about 2% as positive. In the latter two groups, the outbreak of the pandemic determined enterprises to introduce innovations both in their business processes (approximately 20% of industrial enterprises and approximately 40% of service enterprises) and in products (approximately 11% of industrial enterprises and approximately 9% of service enterprises).

4. The main source of outlays on innovative activities in enterprises were domestic funds, the value of which slightly decreased to 92% in 2020, because of the increased absorption of funds from abroad, including EU funds. These funds were primarily used by entrepreneurs for the implementation of development works. Acquired outlays on innovative activities allowed industrial and service entrepreneurs to finance, among others, the purchase of fixed assets, employee training, building the brand and marketing activities.

5. The implementation of innovative activities in enterprises is one of the areas that may constitute a source of competitive advantage; however, it is necessary to remember about appropriate protection for the innovations being developed. In the analysed period, among the forms of protection for innovative solutions, entrepreneurs most often chose business confidentiality and legal and copyright protection. They rarely applied for industrial property rights granted by the PORP or other entities granting such exclusive rights. Among industrial property rights, entrepreneurs most often protected trademarks and inventions.

Summing up the considerations presented in the paper, it should be stated that the conducted preliminary analyses based on GUS data show a great research potential, which should undoubtedly be explored in further studies. At the same time, it should also be emphasised that the

introduction of the new Oslo Manual 2018 guidelines influenced methodological changes in the study of innovativeness of enterprises in Poland, which allowed, on the one hand, the introduction of new research areas to the analyses carried out so far, and on the other, also limited the possibility of comparing the variability of some determinants in the long term.

References

1. Adegbesan, J. A. (2009). On the origins of competitive advantage: Strategic factor markets and heterogeneous Resource complementarity. Academy of Management Review, 34(3), 40632465. doi: 10.5465/amr.2009.40632465

2. Al-Aali, A. Y., & Teece, D. J. (2013). Towards the (strategic) management of intellectual property: Retrospective and prospective. California Management Review, 55(4), 15–30. doi: 10.1525/cmr.2013.55.4.15

3. Anning-Dorson, T. (2018). Innovation and competitive advantage creation: The role of organisational leadership in service firms from emerging markets. International Marketing Review, 35(4), 580–600. doi: 10.1108/IMR-11-2015-0262

4. Anton, J. J., & Yao, D. A. (2004). Little patents and big secrets: Managing intellectual property. The RAND Journal of Economics, 35(1), 1–22. doi: 10.2307/1593727

5. Baruk, J. (2001). Wiedza i innowacje jako źródło przewagi konkurencyjnej. Gospodarka Narodowa, (167)4, 20–34. doi: 10.33119/GN/113895

6. Białoń, L. Janczewska, D. (2006). Menedżer marketingu w firmie przyszłości. [W], L. Białoń (red.) Metody oceny kształcenia specjalistów w zakresie zarządzania, 105–117. Warszawa, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza WSM.

7. Czub, K. (2021). Prawo własności intelektualnej. Warszawa, Poland: Wolters Kluwer.

8. Dereli, D. D. (2015). Innovation management in global competition and competitive advantage. Procedia — Social and Behavioral Sciences, 195, 1365–1370. doi: 10.1016/ j.sbspro.2015.06.323

9. Dobiegała-Korona, B. (2012). Nowa rola marketingu w budowie wartości przedsiębiorstwa. Kwartalnik Nauk o Przedsiębiorstwie, 23(2), 64–75.

10. Drucker, P. F. (1998). On the Profession of Management. Boston, USA: Harvard Business Scholl Press.

11. Drucker, P. (2002). Innowacje i przedsiębiorczość. Praktyka i zasady. Warszawa: PWE.

12. Firlej, K. A. (2012). Innowacyjność polskiej gospodarki jako wyzwanie rozwojowe w warunkach integracji europejskiej. [W] A. Prusek (red.), Wyzwania rozwoju społeczno-ekonomicznego Polski 143–144. Kraków–Mielec, Poland: Katedra Polityki Ekonomicznej

i Programowania Rozwoju Uniwersytetu Ekonomicznego w Krakowie.

13. Freeman, Ch. (1982). The Economics of Industrial Innovation. London, UK: Cassell.

14. Friar, J. H. (1995). Competitive advantage through product performance innovation in a competitive market. Journal of Product Innovation Management, 12(1), 33–42. doi: 10.1016/0737-6782(94)00026-C

15. Gomułka, S. (1998). Teoria innowacji i wzrostu gospodarczego. Warszawa, Poland: CASE.

16. Goyke, K. (2018). Ulga na działalność badawczo-rozwojową jako podatkowa zachęta do ponoszenia nakładów w obszarze B+R. Europa Regionum, 3, 23–36. doi: 10.18276/ er.2018.36-02

17. Granstrand, O. (2006). Innovation and intellectual property rights. [W] J. Fagerberg., & D. C. Mowery (Eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Innovation, 266–290. Oxford, UK: Oxford Academic. doi: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199286805.003.0010

18. Grudzewski, W. M., & Hejduk, I. K. (2004). Metody projektowania systemów zarządzania. Warszawa, Poland: Difin.

19. Grzegorczyk, W. (2011). Strategie marketingowe przedsiębiorstw na rynku międzynarodowym. Łódź, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Łódzkiego.

20. Grzegorczyk, T. (2020). Strategie zarządzania własnością intelektualną. [W] R. Śliwiński (red.), Strategiczne zarządzanie przedsiębiorstwem międzynarodowym, 173–203. Warszawa, Poland: Difin.

21. Grzywacz, W. (1995). Metodyka polityki gospodarczej. Szczecin, Poland: Wydawnictwo PTE.

22. GUS. Działalność innowacyjna przedsiębiorstw w latach 2018–2020. Pobrano 10 sierpnia 2022. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/obszary-tematyczne/nauka-i-technika-spoleczenstwo-informacyjne/nauka-i-technika/dzialalnosc-innowacyjna-przedsiebiorstw-w-latach-2018-2020,2,20.html

23. Hildreth, P., Kimble, Ch. (2004). Knowledge networks: Innovation through communities of practice. Hershey, USA and London, UK: Idea Group Publishing.

24. Holgersson, M. (2013). Patent management in entrepreneurial SMEs. R&D Manage, 43, 21–36. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9310.2012.00700.x

25. Hu, R., Yu, C., Jin, Y., Pray, C., & Deng, H. (2022). Impact of government policies on research and development (R&D) investment, innovation, and productivity: Evidence from pesticide firms in China. Agriculture, 12(5), 709. doi: 10.3390/agriculture12050709

26. Janasz, W., Kozioł-Nadolna, K. (2011). Innowacje w organizacji. Warszawa, Poland: Polskie Wydawnictwo Ekonomiczne.

27. Kamiński, R. (2018). Istota innowacji (definicje, wyznaczniki i rodzaje). [W] R. Kamiński (red.), Innowacje gospodarcze. Wybrane aspekty ekonomiczne i prawne, 13–24. Poznań, Poland: Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM.

28. Kasprzyk, S. (1980). Innowacje od koncepcji do produkcji. Warszawa, Poland: CRZZ

29. Koch, J. (2004). Innowacje siłą napędową rozwoju. [W] J. Gawlik, S. Szelest, M. Trompeteur (red.) Materiały Konferencji Naukowo-Technicznej, Jakość, innowacyjność i transfer technologii w rozwoju przedsiębiorstw INTELTRANS 2006, 91–102, Kraków, Poland: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Krakowskiej.

30. Komor, M. (2022). Political and legal conditions of marketing activity of businesses in the European market. Marketing of Scientific and Research Organizations, 44(2), 1–20.

31. Kotler, Ph. (2004). Marketing od A do Z. Warszawa, Poland: PWE.

32. Kopaliński, W. (2006). Podręczny słownik wyrazów obcych, Warszawa, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Rytm.

33. Lange, O. (1961). Pisma ekonomiczne i społeczne 1930–1960. Warszawa, Poland: PWN.

34. Long, P. O. (1991). Invention, authorship, “Intellectual Property,” and the origin of patents: Notes toward a conceptual history. Technology and Culture, 32(4), 846–884. doi: 10.2307/3106154

35. Major, M., & Niezgoda, J. (2003). Elementy Statystyki Część I. Statystyka opisowa. Kraków: Krakowskie Towarzystwo Edukacyjne Sp. z o.o. na zlecenie Krakowskiej Szkoły Wyższej im. Andrzeja Frycza Modrzewskiego.

36. Marciniak, S. (2010). Innowacyjność i konkurencyjność gospodarki. Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo C.H. BECK.

37. Maurer, S. M., & Scotchmer, S. (2002). The independent invention defence in intellectual property. Economica, 69, 535–547. doi: 10.1111/1468–0335.00299

38. Mokyr, J. (2009). Intellectual property rights, the industrial revolution, and the beginnings of modern economic growth. American Economic Review, 99(2), 349–355.

39. Montoya-Weiss M. M., & Calantone, R. (1994). Determinants of new product performance: A review and meta-analysis, Journal of Product Innovation Management, 11, 397–417.

40. Muça, E., Pomianek, I., & Peneva, M. (2022). The role of GI products or local products in the environment-consumer awareness and preferences in Albania, Bulgaria and Poland. Sustainability, 14(4). doi: 10.3390/su14010004

41. O’Donoghue, T., Scotchmer, S., & Thisse, J. F. (1998). Patent breadth, patent life, and the pace of technological progress. Journal of Economics & Management Strategy, 7, 1–32. doi: 10.1111/j.1430-9134.1998.00001.x

42. Oslo Manual. (2005). Proposed Guidelines for Collecting and Interpreting Technological Innovation Data. Pobrano 10 sierpnia 2022. Retrieved from https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/documents/3859598/5889925/OSLO-EN.PDF

43. Oslo Manual. (2018). Guidelines for Collecting, Reporting and using Data on Innovation, 4th ed, The Measurement of Scientific, Technological and Innovation Activities, by OECD/Eurostat za: Podręcznik Oslo 2018, Zalecenia dotyczące pozyskiwania, prezentowania i wykorzystywania danych z zakresu innowacji, Pomiar działalności naukowo-technicznej i innowacyjnej, GUS, 2020. Pobrano 20 września 2022. Retrieved from https://stat.gov.pl/files/gfx/portalinformacyjny/pl/defaultaktualnosci/5496/18/1/1/podrecznik_oslo_2018_internet.pdf

44. Penc, J. (1999). Innowacje i zmiany w firmie. Transformacja i sterowanie rozwojem przedsiębiorstwa. Warszawa, Poland: Agencja Wydawnicza Placet.

45. Pérez-Luno, A., Valle Cabrera, R., & Wiklund, J. (2007). Innovation and imitation as sources of sustainable competitive advantage. Management Research, 5(2), 71–82. doi: 10.2753/JMR1536-5433050201

46. Pietrasiński, Z. (1970). Ogólne i psychologiczne zagadnienia innowacji. Warszawa, Poland: PWN.

47. Pomykalski, A. (2001). Zarządzanie innowacjami. Warszawa, Poland: PWN.

48. Rozporządzenie Ministra Zdrowia z dnia 20 marca 2020 r. w sprawie ogłoszenia na obszarze Rzeczypospolitej Polskiej stanu epidemii, Dz.U. 2020, poz. 491.

49. Saha, C. N., & Bhattacharya, S. (2011). Intellectual property rights: An overview and implications in pharmaceutical industry. Journal of Advanced Pharmaceutical Technology & Research, 2(2), 88–93. doi: 10.4103/2231-4040.82952

50. Schumpeter, J. (1911). The theory of economic development. New Brunswick, USA and London, UK: Transaction Publishers.

51. Schumpeter, J. (1949). Economic Theory and Entrepreneurial History. [W] R. R. Wohl (Ed.), Change and the Entrepreneur. Postulates and the Patterns for Entrepreneurial History, 131–142. Cambridge, USA: Harvard University Press.

52. Schumpeter, J. Clemence, R. V. (1989). Essays on entrepreneurs, innovations, business cycles and the evolution of capitalism. New Brunswick, USA: Transaction Publishers.

53. Sikora, J., & Uziębło, A. (2013). Innowacja w przedsiębiorstwie — próba zdefiniowania. Zarządzanie i Finanse, 2(2), 351–376.

54. Simpson, P. M., Siguaw, J. A., & Enz, C. A. (2006). Innovation orientation outcomes: The Good and the Bad. Journal of Business Research, 59. doi: 10.1016/j.jbusres.2006.08.001

55. Sławińska, M. (2015). Innowacje marketingowe w działalności przedsiębiorstw handlowych. Annales, Sectio H, XLIX(1), 157–167.

56. Sojkin, B. (2012). Informacyjne podstawy decyzji marketingowych w procesie komercjalizacji produktu. Marketing Instytucji Naukowych i Badawczych, 222, 125–133.

57. Świtalski, W. (2005). Innowacje i konkurencyjność. Warszawa, Poland: Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Warszawskiego.

58. Ustawa z dnia 16 kwietnia 1993 r. o zwalczaniu nieuczciwej konkurencji. Tekst jedn. Dz.U. z 2022 r. poz. 1233.

59. Ustawa z dnia 30 czerwca 2000 r. Prawo własności przemysłowej, Tekst jedn.: Dz.U. z 2021 r. poz. 324.

60. Ustawa z dnia 30 maja 2008 r. o niektórych formach wspierania działalności innowacyjnej. Tekst jedn.: Dz.U. z 2021 r. poz. 706 z późn. zm.

61. Ustawa z dnia 4 lutego 1994 r. o prawie autorskim i prawach pokrewnych. Tekst jedn. Dz.U. z 2021 r. poz. 1062 z późn. zm.

62. Ustawa z dnia 6 marca 2018 r. Prawo przedsiębiorców. Tekst jedn.: Dz.U. z 2022 r. poz. 24 z późn. zm.

63. Whitfield, P. R. (1979). Innowacje w przemyśle. Warszawa, Poland: PWE.

64. Wiśniewska, J. (2017). Ochrona wynalazku w procesie zarządzania działalnością badawczo-rozwojową. Studia i Prace WNEIZ US, 48(3), 307–318. doi:10.18276/ sip.2017.48/3-25

65. Zimon, D., & Gawron-Zimon, Ł. (2014). Wykorzystanie metody QFD do doskonalenia logistycznej obsługi klienta. [W] R. Knosala (red.) Innowacje w zarządzaniu i inżynierii produkcji, Konferencja IZiP, 1077–1084, Opole, Poland: Oficyna Wydawnicza Polskiego Towarzystwa Zarządzania Produkcją.

Agnieszka Bobola, PhD — Warsaw University of Life Sciences — SGGW in Warsaw, Institute of Economics and Finance, Department of Tourism, Social Communication and Counselling. She is a research fellow. Her main academic and research interests focus on intangible value of the enterprise created by intellectual property and social responsibility, which is based on the principles of sustainable development.

Irena Ozimek, Full Professor — Department of Development Policy and Marketing, Institute of Economics and Finance, Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Poland; she works as a scientific researcher and lecturer. Her research focuses on the consumer protection (including consumer education), intellectual property, consumption of goods and services in households and consumer behaviour in the market of goods and services, especially in food market and tourism.

Iwona Pomianek, PhD — Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Institute of Economics and Finance, Department of Development Policy and Marketing. She is a vice-dean of Faculty of Economics. Her main academic and research interests focus on local development, tourism, local government, intellectual property and digital trust.

Joanna Rakowska, dr hab. — Warsaw University of Life Sciences, Poland. Her research focuses on different factors of local and regional sustainable development, and their interconnectedness. She has published three books and more than 100 papers in international journals. She has served as a visiting scholar at the Scotland’s Rural College, the United Kingdom; the University of East London, the United Kingdom; and Agroscope, the Federal Office for Agriculture, Switzerland.