- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Three root causes for the impasse in reputation measuremant for higher education institutions

Joern Redler1*, Petra Morschheuser2

1 School of Business, Mainz University of Applied Sciences, Lucy-Hillebrand-Straße 2, 55128 Mainz, Germany

2 Department for Business Studies, Baden-Wuerttemberg Cooperative State University Mosbach, Arnold-Janssen-Straße 9-13,74821 Mosbach, Germany

1*E-mail: joern.redler@hs-mainz.de

ORCID: 0000-0002-1861-4807

2E-mail: petra-morschheuser@mosbach.dhbw.de

ORCID: 0009-0000-8987-0800

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0008

Abstract:

Monitoring the reputation of Higher Education Institutions is a key challenge. Despite decades of research and theory in Higher Education marketing addressing this issue, a definitive method for capturing and monitoring reputation of such institutions has yet to emerge. This paper argues that research into a theoretically sound method for capturing and monitoring the reputation of Higher Education Institutions has stalled due to three significant obstacles: (a) the complexity of defining the construct of reputation itself, (b) ongoing disputes regarding the appropriate methods of measurement for the constructs of reputation, (c) insufficient tailoring of the construct of reputation to the distinctive nature of Higher Education Institutions.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 52, Issue 2

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0008

P. 26-44

Published July 12, 2024

Three root causes for the impasse in reputation measuremant for higher education institutions

I. The relevance of measuring reputation for the management of Higher Education Institutions

Today’s Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) operate in an increasingly competitive landscape (Garcia-Rodriguez & Gutiérrez-Taño, 2021). Factors such as deregulation, globalization of educational markets, and rising student mobility are contributing to intensified competition among HEIs worldwide. Notably, traditional HEIs from established educational-supplier countries are facing challenges from new rivals, including institutions in Asia and South America that cater to fee-paying international students (Manzoor et al., 2021). Furthermore, different types of HEIs – varying in structural conditions – compete within the same international marketplace for higher education (e.g. Elken & Rosdal, 2017). This competition is particularly evident when comparing public and private universities.

The changing market dynamics coincide with the adoption of new public management practices in public HEIs. Developed in the 1980s, new public management offers an alternative framework for more efficient governance of public organizations (e.g., Broucker et al., 2016). This movement is observed in a number of countries. Particularly in Europe, these shifts reflect broader public sector reforms (de Boer et al., 2007). Notably, funding priorities within Higher Education Institutions are transitioning away from public sources toward non-public funding.

This transformation can be seen, as Wedlin (2008) suggests, as a result of university marketization. HEIs therefore face growing demands for external accountability. Consequently, monitoring practices – originally developed for corporate management – are increasingly developing in higher education environments (e.g., Engwall, 2008; Kethüda, 2023).

A pivotal construct for assessing HEI outcomes is reputation. Reputation serves as a signal of educational and scientific quality, influencing university evaluation and prospective student selection (Hemsley-Brown, 2012; Munisamy et al., 2014). From an institutional economics perspective, reputation’s signaling quality arises because educational and scientific quality cannot be fully evaluated until experienced (Suomi et al., 2014). Following the argument of Plewa et al. (2016), it is precisely this quality that makes reputation a key concept in HEI management in competitive situations.

When applied to HEIs, a good reputation can be interpreted as a long-term expression of the performance and the perceptions of an HEI by its many stakeholders. A good reputation will be related to instilling trust (e.g., Dass et al., 2021), accessing financial support more easily, attracting a higher number of top-quality students, or being of interest for the best researchers, teachers, and administration experts. Studies from a corporate reputation context (e.g., Eberl & Schwaiger, 2005; Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Sabate & Puente, 2003) have revealed a correlation between reputation and financial success, discussing the positive impact of reputation on diverse business goals. Consequently, reputation is appreciated as an intangible asset of organizations, the importance of which is even increasing in business valuation (Brønn, 2008; BrandFinance, 2019).

In today’s marketized landscape, professional monitoring is crucial for managing and marketing HEIs. However, adequate and accepted reputation measures are a prerequisite for effective monitoring. Despite being extensively studied in corporate research, measuring the reputation of HEIs still remains underexplored: while many studies discuss the various facets of reputation measurement for corporations (e.g., Alcaide-Pulido & Gutiérrez-Villar, 2017; Chun, 2005; Walker, 2010), deplorably little research has focused on the question of how reputation in HEI contexts should be measured and monitored.

II. Capturing reputation in HEI contexts – the lack of a feasible approach

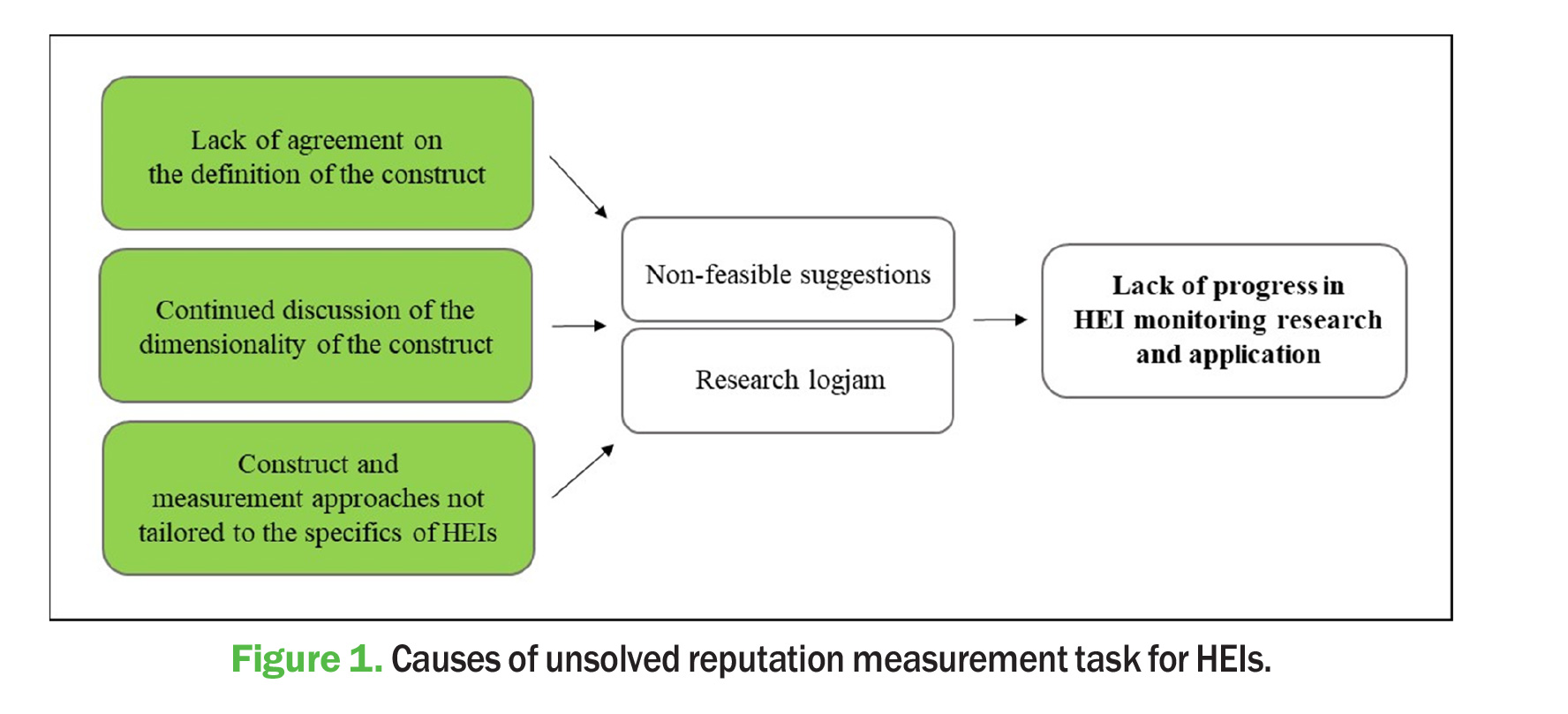

The following sections outline three possible explanations for the logjam in research progress on measuring HEI reputation, which results in a lack of established reputation monitoring systems in HEIs. Figure 1 provides a summary of the argument.

IIa. The reputation construct is not clear, either in terms of its definition or in terms of its its dimensionality

The concept of reputation, extensively examined in business contexts, has been approached from diverse perspectives (e.g., Fombrun & van Riel, 2003; Chun, 2005). In one approach, rooted in Fombrun’s (1996) seminal work, reputation is often defined as the collective perception of an organization held by its stakeholders, shaped by their interactions and received communications (Fombrun & Shanley, 1990; Walker, 2010). Alternatively, reputation may be conceptualized as stakeholders’ assessments of the organization’s ability to meet expectations (e.g., Fombrun & van Riel, 2003), as the collective beliefs about an organization’s identity and prominence (Rao, 1994), or as a set of beliefs encompassing the organization’s capacities, intentions, history, and mission (Carpenter, 2010). Bromley (1993, 2002) and Grunig and Hung (2002) emphasize reputation as shared beliefs among social groups, while Deephouse (1997, 2000) underscores its relation to media visibility and favorability. Gotsi and Wilson (2001) define reputation as stakeholders’ overall evaluation of a company over time, informed by direct experiences or other forms of communication, which is rather similar to Grunig and Hung’s (2002) approach. Note that while reputation and image are intertwined, they represent distinct theoretical constructs (Alcaide-Pulido & Gutiérrez-Villar, 2017; Manzoor et al., 2021).

The discourse surrounding reputation, both intricate and fundamental, has engendered debates about its dimensional structure (which need to be seen as intertwined with the challenges of defining and measuring reputation). Prominent contributions and viewpoints can be compiled as follows:

- Lange et al. (2011) sum up studies and essays which conceptualize reputation in a uni-dimensional way, resulting in three dominant directions: Reputation consisting of familiarity with the organization, reputation consisting of beliefs about what to expect from the organization in the future, and reputation consisting of impressions about the organization’s favorability.

- Examining the application of organizational reputation to public administration, Carpenter (2010) distinguishes four dimensions. The performative dimension is related to stakeholders’ perceptions and evaluation of whether an organization delivers outputs that comply with its mission and activities (also Chapleo et al., 2011). In a way, this dimension refers to aspects of effectiveness and efficiency. The procedural dimension deals with the appropriateness of an organization’s procedural and legal requirements in its decision making. The technical dimension, in turn, draws attention to the knowledge and competencies within the organization which are necessary to handle complex tasks and changing environments. Finally, the moral dimension of reputation refers to the stakeholders’ perceptions of whether an organization is honest, humane, even emotionally appealing (Carpenter & Krause, 2012). These dimensions also reflect evaluations of whether an organization protects the interests of stakeholders and members. As these various authors point out, reputation should not be seen one-dimensional; however one consequence of a multi-dimensional construct is the complicating issue that striving to boost one dimension implies that another dimension will most likely suffer: trade-offs are inherent. Consequently, organizations will strive to prioritize certain forms of reputation, e.g., the performative reputation, over others. To further add to the complication, different parts of the organization may favor and support different dimensions of reputation.

- Fombrun and colleagues have developed a reputation definition for a marketing context, using a more specific operationalization (Fombrun, 1996; Fombrun et al., 2000; Fombrun & van Riel, 2003). Their work, in turn, has served as one basis for the approach proposed by Eisenegger and Imhof (2009). They crafted a three-dimensional reputation approach by combining the reputation concept of Eberl and Schwaiger (2005) (who distinguished cognitive and affective reputations) with a normative dimension. The derived framework includes a functional, a social and an expressive dimension. The functional reputation refers to success and competence of the actor that can be expressed through key figures or ratings (Eisenegger & Imhof, 2009). On top of this, a successful organization needs to adhere to the norms and values of society; this denotes the social reputation. While the first two dimensions focus more on the outside world, the individual world of the actor itself becomes the object of the expressive dimension. In other words, the emotional attractiveness, authenticity, or uniqueness of the organization is reflected in this third dimension. According to Eisenegger (2004, 2005, 2009), the three-dimensional reputation concept should have universal applicability and should be relevant to all types of organizations.

- Agarwal et al. (2015) propose as many as six dimensions – basing reputation on stakeholders’ perceptions of quality level, vision, workplace, responsibility, financial performance, and emotional appeal.

- The discussion about the dimensionality of reputation, on the one hand, and the debate about inherent trade-offs between them as advanced by Carpenter (2010) and Carpenter and Krause (2012), on the other, both lend support to the idea of different sub-types of reputation as we have presented in Morschheuser and Redler (2015). Building on the notion of scientific organizations as multi-sectional organizations, we have argued that scientific organizations’ reputations should be understood as being composed of four sub-reputations: reputation of administration (stakeholders’ perceptions about administrative performance), reputation of research (stakeholders’ perceptions about research performance), reputation of transfer (stakeholders’ perceptions about transfer performance) and reputation of teaching (stakeholders’ perceptions about teaching performance).

In summary, various conceptualizations of the reputation construct have been discussed, all of them having their origins in the study of business. Nevertheless, no consistent understanding of the dimensional structure of this phenomenon has yet emerged from this research.

IIb. There are many unresolved discussions regarding the appropriate measurement methods to apply to HEI reputation

The preceding discussion highlights that reputation is linked to a number of factors, which therefore presents challenges for its measurement and monitoring. One challenge lies in accurately measuring each factor, while another involves linking them to indicators of the overarching construct. A review of the literature on appropriate quantitative measurement design reveals several ambiguities and trade-offs, likely reflecting more general disputes. These ambiguities cause significant headaches for reputation managers, who struggle to design appropriate reputation management tools. Such ambiguities often lead to initiatives going round in circles. The main ambiguities are as follows: Subjective vs. objective measures: There is a debate about whether to use measures based on “objective” data or ones based on “subjective” data (e.g., Siefke, 1998). The first approach relies on intersubjectively verifiable measures and assumes that reputation can be measured using neutral third parties or objective and external indicators that are not subject to distorted perceptions. Examples include the use of figures and performance indicators or observational data. In contrast, methods based on subjective data accept intersubjectively different perceptions and apply measures that can capture these. Scale-based measures, incident-based procedures or problem-based assessments are examples of this type of approach.

Formative vs. reflective measurement: The formative vs. reflective measurement controversy concerns how the factors within reputation are combined and whether they are a cause or a result of the construct under investigation. Helm (2005, p. 96) points out that “most researchers assume a reflective relationship, meaning that the observed latent variable is assumed to be a construct of all its indicators.” According to this reflective perspective, the observable factors change as the latent variable changes (e.g. reputation) – they “reflect“ the latent variable (an “eliciting variable,” Rossiter, 2002). Formative measurement takes a different perspective. In a formative view, the factors cause the latent variable, they “form” it (a “formed variable,” Rossiter, 2002; Diamantopoulos et al., 2008). While Agarwal et al. (2015, p. 448) conceptualize (corporate) reputation as a reflective construct, the many indices or rankings are expressions of the formative approach. As Helm (2005) reminds us, these are “classic examples of formative construct conceptualisation” and, as is well known, they are often used to express reputation. A more recent overview of the reflective-formative debate can be found in Fleuren et al. (2018).

Measures for first-order vs. second-order constructs: Agarwal et al. (2015) discuss, among other things, whether reputation is a first-order or a second-order construct. While a first-order construct has observable variables as indicators, a second-order structure implies that the original construct (here: reputation) is an unobservable (latent) variable and has other latent variables as indicators. There seems to be theoretical grounds and empirical evidence for considering reputation as a second-order construct based on individual measurement dimensions (Agarwal et al., 2015). Similar paths, but for different objects of reputation, are outlined in papers by Dong et al. (2019) and Walsh and Beatty (2007). Although coming from different contexts, papers by Danneels (2016) and Potter (1991), for example, provide a deeper insight into the specifics of measuring first- or second-order constructs.

Single-item vs. multi-item measures: Theoretical considerations have also focused on whether a construct (such as reputation) should be measured by a single-item or multi-item measure. While single-item scales use only one item (question or indicator) to capture a construct, multi-item measures use a variety of items to assess the empirical situation of a construct. Today, the use of multi-item scales seems to be the standard in academic research. However, the conventional wisdom (in marketing research) has been challenged by Bergkvist and Rossiter (2007), referring to ideas of the C-OAR-SE procedure proposed by Rossiter (2002). In general, single-item measurement is discussed because of several advantages (see Sarstedt & Wilczynski, 2009, or Bowling, 2005, for an overview), such as higher response rates, simplicity, increased flexibility, or lower costs. However, as Sarstedt and Wilczynski (2009) point out, the arguments in favor of single item measures apply only to reflective measures, as classical psychometric performance criteria are not applicable to formative constructs. On the other hand, there are convincing arguments in favor of multi-item measures (e.g. Sarstedt & Wilczynski, 2009, for a review), such as increased reliability, higher construct validity or better predictive validity (e.g. Diamantopoulos et al., 2012). For the higher education context, Svensson (2008) examines the measures underlying scientific journal rankings and finds that these rankings are largely based on single-item measures (e.g., expert perceptions or citations) and therefore fail to provide estimates of psychometric quality such as reliability or validity. Consequently, he recommends the use of broader approaches based on multi-item measures.

In summary, notable sub-questions of the overall measurement problems are still left unanswered by measurement and scaling theory; rather, the discussion points to several forks in the road that need to be taken if a solution for measuring HEI reputation is to be derived. This is another reason why ideas about what might provide a sound solution for measuring HEI reputation have not yet been established.

IIc. Traditional reputation measurement is poorly tailored to the distinctive nature of HEIs

Many authors understand HEIs as any institutions involved in higher education, which includes all educational institutions authorized to provide two to three years of post-secondary education (e.g. World Conference on Higher Education, 1998; McCaffrey, 2019). When discussing educational strategies, Pucciarelli and Kaplan (2016) highlight that universities (as HEIs) have three basic missions: teaching, research and public service, which have always been in conflict. HEIs can take many forms, for example they can be public vs. private, non-profit vs. for-profit, specialized in particular disciplines vs. very broad, focused on research vs. teaching vs. both. HEIs produce teaching, research and transfer outputs. In Morschheuser and Redler (2015), we have discussed HEIs as a subtype of Scientific Organizations, which we define as tetra-sectional social systems that act in a goal-oriented way, produce knowledge or know-how, use and defend scientific methods, share their insights and ways of research with the public for the purpose of discussion, quality control and stimulation of further research, and are embedded in a complex network of stakeholders.

It is important to note that HEIs differ from corporate organizations in a number of significant ways. For instance, the literature has identified certain unique characteristics of HEIs:

- Telem (1981, p. 581) emphasizes that HEIs are large organizations that deal with thousands of students across various academic levels and programs. HEIs have hundreds of faculty members and administrative staff, numerous buildings, significant financial turnover, and a variety of research programs. This description highlights the size of the organization and the various stakeholders involved, as well as the complexity that characterizes HEIs, including the notion of multiple interrelated subsystems. Barnett (2015) illustrates that HEIs face super-complexity on several levels. Therefore, it is not surprising that HEIs are often described as one of the most complex organizational forms (Austin & Jones, 2015). Cohen et al. (1972) and Cohen & March (1974) have described HEI as “organized anarchy,” a term also acknowledged by Perkins (1973). For instance, no one holds absolute authority in a typical HEI.

- A related idea is that of HEIs as “loosely coupled systems” (Weick, 1976, p. 1).

- HEIs have a normative character, and Birnbaum (1988) emphasizes the typical roles of referent and expert power. According to Birnbaum, HEIs are unique organizations because they have little specialization of work but much specialization of expertise, a comparatively flat hierarchy, and a less visible role performance.

- Birnbaum (1988) and Perkins (1973) both argue that accountability for cause and effect is low in HEIs.

- HEIs have been described as tetra-sectional, integrating four distinct organizations into one. This concept is supported by research from Barnett (2003) and Kerr (1972), who both propose the idea of an internally fragmented “multiversity.”

These arguments support the conclusion that HEIs cannot easily be compared to business organizations. Furthermore, there are issues with the market-related assumptions that have been implied in corporate reputation research. While firms operate within a market system, HEIs do not. Firms interact with a market that consists of suppliers and demand as the main actors. The interaction of supply and demand creates efficient solutions for all parties involved, resulting in the creation of value (Sheth & Uslay, 2007).

The discussion of reputation in the context of HEIs has so far left certain aspects insufficiently considered – such as measuring and monitoring issues. Additionally, the current theory on reputation in HEIs is not specific and instead refers to reputation as it originated from business research (as we have noted, the conceptualizations of reputation outlined above are largely from business backgrounds). Returning to the key authors who have worked on defining reputation, such as Fombrun (1996), Fombrun and Shanley (1990), Walker (2010), or Fombrun and van Riel (2003), it is clear that their focus is on enterprises. As research has not yet addressed whether the concept of reputation and its related measurement solutions can be adequately applied to HEIs, or what adaptations may be necessary, this remains an important area for future investigation.

III. The current landscape: a scarcity of research on measuring HEI reputation

As a kind of interim summary of the above discussion, we can state that it appears that the issue of measuring HEI reputation has not yet gained much attention. Only a limited number of tailored research contributions can be identified that examine HEI reputation at all.

Theus (1993), for instance, explores how university reputations develop and fade; moreover, she investigates attributes of reputation. Conard and Conard (2000) conducted a study with high school seniors to investigate the factors that contribute to a college’s reputation, including academic quality, career preparation, ethos, and exclusivity. Suomi’s (2014) findings emphasize the multidimensionality of the reputation construct in HEI backgrounds. The relationship between reputation and student loyalty has been investigated by various scholars, including Nguyen and Leblanc (2001) and Garcia-Rodriguez and Gutiérrez-Taño (2021). Their studies have found that reputation has a positive effect on loyalty. Ressler and Abratt (2009) propose a framework for managing and testing university reputation. Vidaver-Cohen (2007) previously introduced a reputation model for higher education institutions, applying findings from reputation research to business schools. In certain academic papers, the perception of HEI reputation is often associated with branding concepts, including constructs such as university brands (Dass et al., 2021; Khoshtaria et al., 2020). Examples of this can be found in Chapleo (2004) and Balmer and Liao (2007).

IV. Conclusions and call to action

As we have sought to show in this paper, professional monitoring is crucial for managing the reputation of HEIs in today’s marketized landscape. However, to manage reputation effectively, it is necessary to measure it adequately. Nevertheless, as we have outlined above, there are serious problems with finding an acceptable and feasible way of measuring reputation that accounts for the specifics of HEIs.

Three main reasons have been highlighted to explain this situation: (a) that notable sub-questions of the overall measurement problems are still left unanswered, (b) that there are several, sometimes incommensurate, (construct-related) demands that need to be met for the same measurement task, and (c) that the generic challenges become further exacerbated when it comes to adapting these views more specifically to HEI reputation measurement and monitoring.

To resolve the resulting impasse and help facilitate discussion, several options might be worth considering (for a more detailed view see Redler & Morschheuser, 2024). One option could be to advance both basic HEI theory and reputation theory. This stream could include a thorough evaluation of what reputation means in the context of HEI, acknowledging that the objective of reputation needs to play a more prominent role in monitoring issues. When considering HEIs, it is important to determine which characteristics are relevant and how they can be measured accurately.

Another approach might be to concentrate on practical solutions. To maintain traditional perspectives in reputation research and to make them valuable, it is necessary to be more direct and to assess the usefulness of proposed measurement guidelines in actual HEI management. This involves researchers stepping outside of their own narrow definitions and considering alternative perspectives on what constitutes appropriate measurement. Rather than producing more findings that add another small piece to the silo-based construction of reality, researchers need to devote time and resources to research that contributes to knowledge that has an impact on the reality of (HEI) managers. To do so, researchers may benefit from engaging with managers to analyze their views, understand their needs and behaviors, and use these insights to inform research strategies. Acceptance of more pragmatic solutions for measuring HEI reputation may be an outcome of engaging with the practical views of HEI managers. It should be noted that these solutions may not meet all requirements for optimal measurement from a theoretical perspective.

An alternative approach could be to focus on constructs that have a more widely accepted definition and valid measures, such as brand equity (Khoshtaria et al., 2020) or image (Alcaide-Pulido & Gutiérrez-Villar, 2017), rather than relying on the reputation approach.

Finally, it may be worthwhile to explore the use of a scorecard to assess the reputation of an HEI. This approach shows potential, but it is crucial to first identify the HEI’s needs before determining the measurement dimensions, as suggested by Suomi (2014) or Nicolescu (2009). It may also be necessary to discard current constructs and their operationalizations and consider both qualitative and quantitative perspectives. Overall, there are valid reasons to use scorecard concepts as a starting point for new initiatives, particularly the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) developed by Kaplan and Norton (1996). As the originators of the scorecard view point out, “measurement was as fundamental to managers as it was for scientists” (Kaplan, 2009, p. 1253). The scorecard lens has an important advantage in that it approaches construct and measurement issues in a more integrative way.

References

Agarwal, J., Osiyevskyy, O., & Feldman, P.M. (2015). Corporate reputation measurement: Alternative factor structures, nomological validity, and organizational outcomes. Journal of Business Ethics, 130(2), 485–506. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-014-2232-6

Alcaide-Pulido, P., Alves, H., & Gutiérrez-Villar, B. (2017). Development of a model to analyze HEI image: a case based on a private and a public university. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 27(2), 162–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 08841241.2017.1388330

Austin, I., & Jones, G. A. (2015). Governance of higher education: Global perspectives, theories, and practices. Routledge.

Baldridge, J. V., Curtis, D. V., Ecker, G., & Riley, G. L. (1978). Policy making and effective leadership: A national study of academic management. Jossey-Bass.

Balmer, J. M. T., & Liao, M. (2007). Student corporate brand identification: An exploratory case study. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 12(4), 356–375. https://doi.org/10.1108/13563280710832515 Barnett, R. (2003). Beyond all reason. Living with ideology in the university. SRHE and Open University Press.

Barnett, R. (2015). Understanding the university: Institution, idea, possibilities. Routledge.

Bergkvist, L., & Rossiter, J. (2007). The predictive validity of multiple-item versus single-item measures of the same constructs. Journal of Marketing Research, 44(2), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkr.44.2.175 Birnbaum, R. (1988). How colleges work: The cybernetics of academic organization and leadership. Jossey-Bass Publishers.

Bowling A. (2005). Just one question: If one question works, why ask several? Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 59(5), 342–345. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/jech.2004.021204 BrandFinance (Ed.) (2019). Global intangible finance tracker (GIFT) – An annual review of the worlds intangible value. Brand Finance.

Bromley, D. B. (1993). Reputation, image and impression management. John Wiley & Sons.

Bromley, D. B. (2002). An examination of issues that complicate the concept of reputation in business studies. International Studies of Management & Organization, 32(3), 65–81. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40397542 Broucker, B., De Wit, K., & Leisyte, L. (2016). Higher education reform: A systematic comparison of ten countries from a new public management perspective. In R. Prichard, A. Pausitis, & J. Williams (Eds.), Positioning Higher Education Institutions (pp. 19–40). Brill.

Brønn, P. S. (2008). Intangible assets and communication. In A. Zerfass, B. van Ruler & K. Sriramesh (Eds.), Public relations research (pp. 281–291). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Carpenter, D. (2010). Reputation and power: Organizational image and pharmaceutical regulation at the FDA. Princeton University Press.

Carpenter, D. P., & Krause, G. A. (2012). Reputation and public administration. Public Administration Review, 72(1), 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2011.02506.x Chapleo, C. (2004). Interpretation and implementation of reputation/brand management by UK university leaders. International Journal of Educational Advancement, 5(1), 7–23. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.ijea.2140201

Chapleo, C., Carrillo Durán, M. V., & Castillo Díaz, A. (2011). Do UK universities communicate their brands effectively through their websites? Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 21(1), 25–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241. 2011.569589 Chun, R. (2005). Corporate reputation: Meaning and measurement. International Journal of Management Reviews, 7(2), 91–109. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2005.00109.x

Cohen, M. D., & March, J. G. (1974). Leadership and ambiguity: The American College President. McGraw-Hill.

Cohen, M. D., March, J. G., & Olsen, J. P. (1972). A garbage can model of organizational choice. Administrative Science Quarterly, 17(1), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392088

Conard, M. J., & Conard, M. A. (2000). An analysis of academic reputation as perceived by consumers of higher education. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 9(4), 69–80. https://doi.org/10.1300/J050v09n04_05

Dass, S., Popli, S., Sarkar, A., Sarkar, J. G., & Vinay, M. (2021). Empirically examining the psychological mechanism of a loved and trusted business school brand. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 31(1), 23–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1742846

Danneels, E. (2016). Survey measures of first-and second-order competences. Strategic Management Journal, 37(10), 2174–2188. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2428

de Boer, H., Enders, J., & Schimank, U. (2007). On the way towards new public management? The governance of university systems in England, the Netherlands, Austria, and Germany. In D. Jansen (Ed.), New forms of governance in research organizations (pp. 137–152). Springer.

Deephouse, D. L. (1997). Part IV – How Do Reputations Affect Corporate Performance?: The effect of financial and media reputations on performance. Corporate Reputation Review, 1, 68–72. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr. 1540019

Deephouse, D. L. (2000). Media reputation as a strategic resource: An integration of mass communication and resource-based theories. Journal of Management, 26(6), 1091–1112. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630002600602

Diamantopoulos, A., Riefler, P., & Roth, K. P. (2008). Advancing formative measurement models. Journal of Business Research, 61(12), 1203–1218. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2008.01.009

Diamantopoulos, A., Sarstedt, M., Fuchs, C., Wilczynski, P., & Kaiser, S. (2012). Guidelines for choosing between multi-item and single-item scales for construct measurement: A predictive validity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 40(3), 434–449. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-011-0300-3

Dong, Y., Sun, S., Xia, C., & Perc, M. (2019). Second-order reputation promotes cooperation in the spatial prisoner’s dilemma game. IEEE Access, 7, 82532–82540. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2019.2922200

Eberl, M., & Schwaiger, M. (2005). Corporate reputation: Disentangling the effects on financial performance. European Journal of Marketing, 39(7–8), 838–854. https://doi.org/10.1108/03090560510601798

Eisenegger, M. (2004): Reputationskonstitution in der Mediengesellschaft. In K. Imhof, R. Blum, H. Bonfadelli, & O. Jarren (Eds.), Mediengesellschaft. Strukturen, Merkmale, Entwicklungsdynamiken (pp. 262–292). Springer.

Eisenegger, M. (2005). Reputation in der Mediengesellschaft – Konstitution, issues monitoring, issues management. VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Eisenegger, M. (2009). Trust and reputation in the age of globalisation. In J. Klewes & R. Wreschniok (Eds). Reputation capital, (pp. 11–22). Springer.

Eisenegger, M., & Imhof, K. (2009). Funktionale, soziale und expressive Reputation – Grundzüge einer Reputationstheorie. In U. Röttger (Ed.), Theorien der Public Relations, (pp. 243–264). VS Verlag für Sozialwissenschaften.

Elken, M., & Rosdal, T. (2017). Professional higher education institutions as organizational actors. Tertiary Education and Management, 23, 376–387.

Engwall, L. (2008). The university: A multinational corporation? In L. Engwall & D. Weaire (Eds.), The university in the market, (pp. 9–21). Portland Press.

Fleuren, B. P., van Amelsvoort, L. G., Zijlstra, F. R., de Grip, A., & Kant, I. (2018). Handling the reflective-formative measurement conundrum: A practical illustration based on sustainable employability. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 103, 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2018.07.007

Fombrun, C. J. (1996). Reputation. Realizing value from the corporate image. Harvard Business School Press.

Fombrun, C. J., & Shanley M. (1990). What’s in a name? Reputation building and corporate strategy. Academic Management Journal, 33(2), 233–258. https://doi.org/10.2307/256324 Fombrun, C. J., & van Riel, C. (2003). Fame & fortune. How successful companies build winning reputations. Pearson.

Fombrun, C. J., Gardberg, N. A., & Sever, J. M. (2000). The reputation quotient SM: A multi-stakeholder measure of corporate reputation. Journal of Brand Management, 7(4), 241–255. https://doi.org/10.1057/bm.2000.10

García-Rodríguez, F. J., & Gutiérrez-Taño, D. (2021). Loyalty to higher education institutions and the relationship with reputation: an integrated model with multi-stakeholder approach. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2021.1975185

Gotsi, M., & Wilson, A.M. (2001). Corporate reputation: Seeking a definition. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 6(1), 24–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/ 13563280110381189

Grunig, J., & Hung, C. (2002, March 8-10). The effect of relationships on reputation and reputation on relationships: a cognitive, behavioral study [Paper Presentation]. PRSA Educator’s Academy 5th Annual International Interdisciplinary Public Relations Research Conference, Miami.

Helm, S. (2005). Designing a formative measure for corporate reputation. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(2), 95–111. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540242

Hemsley-Brown, J. (2012). The best education in the world: Reality, repetition or cliché? International students’ reasons for choosing an English university. Studies in Higher Education, 37(8), 1005–1022. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079. 2011.562286

Kaplan, R. S. (2009). Conceptual foundations of the balanced scorecard. In C. S. Chapman, A. G. Hopwood & M. D. Shields (Eds.), Handbooks of management accounting research (Vol. 3, pp. 1253–1269). Elsevier.

Kaplan, R. S., & Norton, D. P. (1996). The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy Into Action. Harvard Business School Press.

Kerr, C. (1972). The uses of the university. Cambridge.

Kethüda, Ö. (2023). Positioning strategies and rankings in the HE: congruence and contradictions. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 33(1), 97–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2021.1892899

Khoshtaria, T., Datuashvili, D., & Matin, A. (2020). The impact of brand equity dimensions on university reputation: an empirical study of Georgian higher education. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 30(2), 239–255. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841241.2020.1725955

Lange, D., Lee, P. M., & Dai, Y. (2011). Organizational reputation: A review. Journal of Management, 37(1), 153–184. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206310390963

Manzoor, S. R., Ho, J. S. Y., & Al Mahmud, A. (2021). Revisiting the ‘university image model’ for higher education institutions’ sustainability. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 31(2), 220–239. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 08841241.2020.1781736 McCaffery, P. (2019). The higher education manager’s handbook effective leadership and management in universities and colleges. Routledge.

Morschheuser, P., & Redler, J. (2015). Reputation management for scientific organisations — Framework development and exemplification. Journal of Marketing of Scientific and Research Organizations (MINIB), 18(4), 1–36. https://doi.org/10.14611/minib.18.04.2015.08

Munisamy, S., Jafaar, N. I. M., & Nagaraj, S. (2014). Does reputation matter? Case study of undergraduate choice at a premier university. Asia-Pacific Education Research, 23(3), 451–462. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0120-y

Nicolescu, L. (2009). Applying marketing to higher education: Scope and limits. Management & Marketing, 4(2), 35–44.

Nguyen, N., & Leblanc, G. (2001). Corporate image and corporate reputation in customers’ retention decisions in services. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services, 8(4), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0969-6989(00)00029-1

Perkins, J. A. (1973). The university as an organization. McGraw-Hill.

Plewa, C., Ho, J., Conduit, J., & Karpen, I. O. (2016). Reputation in higher education: A fuzzy set analysis of resource configurations. Journal of Business Research, 69(8), 3087–3095. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2016.01.024

Potter, W. J. (1991). The relationships between first-and second-order measures of cultivation. Human Communication Research, 18(1), 92–113. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1468-2958.1991.tb00530.x

Pucciarelli, F., & Kaplan, A. (2016). Competition and strategy in higher education: Managing complexity and uncertainty. Business Horizons, 59(3), 311–320.

Rao, H. (1994). The social construction of reputation: Certification contests, legitimation, and the survival of organizations in the American automobile industry: 1895–1912. Strategic Management Journal, 15(S1), 29–44. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250150904

Redler, J., & Morschheuser, P. (2024). Somehow bogged down: why current discussions on measuring HEI reputation go round in circles, and possible ways out. Journal of Marketing for Higher Education, 1–25. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/08841241.2024.2305637

Ressler, J., & Abratt, R. (2009). Assessing the impact of university reputation on stakeholder intentions. Journal of General Management, 35(1), 35–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/030630700903500104

Rossiter, J. R. (2002). The C-OAR-SE procedure for scale development in marketing. International Journal of Research in Marketing, 19(4), 305–335. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0167-8116(02)00097-6

Sabate, J. M. de la Fuente, & Puente, E. de Quevedo (2003). Empirical analysis of the relationship between corporate reputation and financial performance: A survey of the literature. Corporate Reputation Review, 6(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1540197

Sarstedt, M., & Wilczynski, P. (2009). More for less? A comparison of single-item and multi-item measures. Die Betriebswirtschaft, 69(2), 211–227. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/281306739_More_for_Less_A_Comparison_of_Single-item_and_Multi-item_Measures

Sheth, J. N., & Uslay, C. (2007). Implications of the revised definition of marketing: from exchange to value creation. Journal of Public Policy & Marketing, 26(2), 302–307.

Siefke, A. (1998). Zufriedenheit mit Dienstleistungen: ein phasenorientierter Ansatz zur Operationalisierung und Erklärung der Kundenzufriedenheit im Verkehrsbereich auf empirischer Basis. Peter Lang.

Suomi, K. (2014). Exploring the dimensions of brand reputation in higher education – A case study of a Finnish master’s degree programme. Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management, 36(6), 646–660. https://doi.org/10.1080/ 1360080X.2014.957893

Suomi, K., Kuoppakangas, P., Hytti, U., Hampden-Turner, C., & Kangaslahti, J. (2014). Focusing on dilemmas challenging reputation management in higher education. Journal of Educational Management, 28(4), 261–478. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/IJEM-04-2013-0046

Svensson, G. (2008). Scholarly journal ranking(s) in marketing: Single-or multi-item measures? Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 26(4), 340–352. https://doi.org/ 10.1108/02634500810879250

Telem, M. (1981). The institution of higher education – A functional perspective. Higher Education, 10(5), 581–596. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01676903

Theus, K. T. (1993). Academic reputations: The process of formation and decay. Public Relations Review, 19(3), 277–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/0363-8111 (93)90047-G

Vidaver-Cohen, D. (2007). Reputation beyond the rankings: A conceptual framework for business school research. Corporate Reputation Review, 10(4), 278–304. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.crr.1550055

Walker, K. (2010). A systematic review of the corporate reputation literature: Definition, measurement, and theory. Corporate Reputation Review, 12(4), 357–387. https://doi.org/10.1057/crr.2009.26

Walsh, G., & Beatty, S. E. (2007). Customer-based corporate reputation of a service firm: Scale development and validation. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 35(1), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11747-007-0015-7

Wedlin, L. (2008). University marketization: The process and its limits. The University in the Market, 84, 143–153.

Weick, K. E. (1976). Educational organizations as loosely coupled systems. Administrative Science Quarterly, 21(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.2307/2391875

World Conference on Higher Education (1998). World declaration on higher education for the twenty-first century: Vision and action. Retrieved August 21, 2022, from https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000141952

Dr. Joern Redler is a Full Professor of Marketing a Mainz University of Applied Sciences, Germany. His teaching and research focus on brand management and POP communication. He holds a Doctorate in Economic Sciences from Justus-Liebig-University Gießen, Germany, and has held several marketing management positions at private sector companies. Redler is currently co-spokesperson of the AfM – German Network of Professors of Marketing – as well as Dean of the Business School at Mainz University of Applied Sciences.

Prof. Petra Morschheuser has been Professor for Sustainable Management and Controlling at the DHBW Mosbach since 2010. She studied business administration and business education in Saarbrücken and Nuremberg. After graduating in 1994, she worked as a research assistant at the Chair of Business Informatics in Nuremberg, where she received her doctorate in 1998. After her doctorate, she held various management positions, including project manager in an extensive M&A project for a retail group, head of investment management and corporate development for an insurance company, head of urban development and, since 2002, senior partner in a management consultancy she co-founded. In 2012, she was awarded the “Innovation in Teaching” scholarship of the BadenWürttemberg Foundation. Since 2012/2013 she has been a member of “Lehre hoch n – Das Bündnis für Hochschullehre”. She is also scientific director of the Competence Center of Scientific Working at the DHBW Mosbach, scientific director of a master’s program at the DHBW CAS and an elected member of the senate.