- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Where is the social impact? Key barriers to knowledge valorisation

Magdalena Grębosz-Krawczyk1, Mateusz Sowa2

1 Lodz University of Technology, Institute of Marketing and Sustainable Development,

8 Politechniki Ave., 93-590 Łódź, Poland

2 Lodz University of Technology, Institute of Management,

221 Wólczańska St., 93-005 Łódź, Poland

1 E-mail: magdalena.grebosz@p.lodz.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-8339-2270

2 E-mail: magdalena.grebosz@p.lodz.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-8339-2270

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2025-0001

Abstract:

Knowledge valorisation, the process of transforming research outputs into societal, economic, and environmental value, remains a significant challenge for many research institutions, particularly in achieving measurable social impact. While knowledge commercialisation has gained prominence, the broader valorisation process is hindered by barriers that are often poorly understood. This study explores these barriers through partially standardized, in-depth interviews conducted in 2023 with representatives from 13 research units across five countries. Key findings reveal that researchers face constraints such as insufficient time, lack of awareness, and limited engagement, compounded by inadequate financial support for valorisation projects. A novel barrier identified is the absence of robust metrics to assess social impact – a critical gap not observed in knowledge commercialisation. These insights provide actionable recommendations for researchers, managers, and university leaders to enhance the knowledge valorisation process and its societal contributions. The study underscores the need for systemic changes to address these challenges and foster impactful collaborations between academia and broader society.

MINIB, 2025, Vol. 55, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2025-0001

P. 1-16

Published March 19, 2025

Where is the social impact? Key barriers to knowledge valorisation

1. Introduction

Effective knowledge valorisation should lead to economically, societally and environmentally relevant outcomes (Cain et al., 2018; van de Burgwal et al., 2019; De Silva & Vance, 2017). Consequently, knowledge valorisation assumes that the data, research results and solutions developed by research groups can be transformed into sustainable products, processes and services, as well as knowledge-based policies that deliver economic value and benefit society (European Commission, 2023; European Council, 2022).

To achieve this, however, it is necessary for universities and research units to open up and engage more actively with the business and social environment. Recent amendments to legal regulations have steered the activities of research units towards this broader mission of societal progress. This mission encompasses not only the application of research outputs but also the process of generating value from scientific knowledge throughout its lifecycle – starting from initial inquiry to its application in economic and social contexts. Countries like the Netherlands, Ireland, and Canada have adopted national policies and implemented programs aimed at fostering stronger engagement of scientists in valorisation processes (Cain et al., 2018; European Commission, 2020, Hladchenko, 2016).

Nevertheless, the success of knowledge valorisation depends on identifying and addressing the main barriers to collaboration between universities and their environment. While many existing studies focus on the barriers to knowledge transfer or commercialisation (e.g. Baycan and Stough, 2013; Beyer, 2022; Czemiel-Grzybowska and Brzeziński, 2015; D’Este et al., 2012; O’Reilly and Cunningham, 2017; van de Burgwal et al., 2019), rarely is there any discussion seeking to identify the key barriers specifically to the broader concept of knowledge valorisation. Unlike knowledge transfer or commercialisation, knowledge valorisation involves not only technological and economic, but also social and environmental impacts.

This article addresses this critical gap in understanding the barriers to knowledge valorisation. Its primary objective is to identify the key obstacles that hinder effective valorisation processes, drawing on the experiences of research institutions worldwide.

2. Theoretical bacground

Knowledge valorisation has been defined as “the process of creating social and economic value from knowledge by linking different areas and sectors and by transforming data, know-how and research results into sustainable products, services, solutions and knowledge-based policies that benefit society” (European Commission, 2020). On this view, the concept encompasses both technological and non-technological solutions that can benefit society; knowledge valorisation should involve different actors of the research and innovation ecosystem, including researchers, businesses, users, citizens and policy makers.

Knowledge valorisation is also understood as the creation of societal value from knowledge by translating research findings into innovative products, services, processes, and/or business activities (Benneworth & Jongbloed, 2010; Hladchenko, 2016). This process often involves knowledge-related collaborations between academic researchers and non-academic organizations (Perkmann et al., 2013), utilizing various informal and formal channels that reinforce each other (Jacobsson & Perez Vico, 2010). Moreover, knowledge valorisation extends beyond simply disseminating research results outside the academic community – it is also associated with the co-creation of knowledge by scientists and representatives from different organisations (Benneworth & Jongbloed, 2010).

It is important to distinguish knowledge valorisation from knowledge commercialisation. Knowledge commercialisation is the process of converting innovative ideas into economic profit streams, through activities related to making research results available to partners for a fee or transferring the results to such partners. In this context, it requires transfer and implementation, which together result in increased profits and added value (Salehi et al., 2022). In the case of knowledge valorisation, it is the social and/or environmental impact that is crucial.

The social impact strictly connected with knowledge valorisation is rarely the result of direct transfer of scientific results, and the success of university knowledge valorisation policies is, among other things, strongly dependent on the involvement of individual actors in knowledge valorisation processes (Derrick & Bryant, 2013).

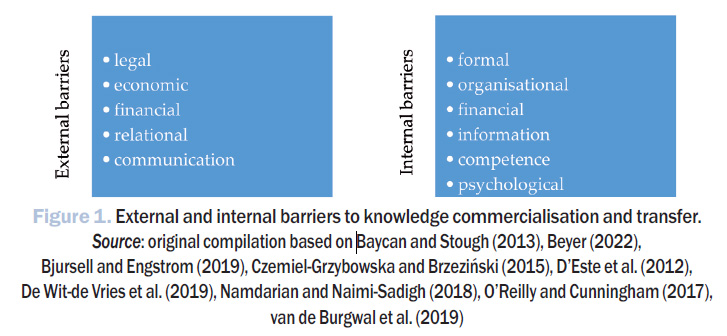

In spite of widespread institutional policies that encourage engagement with the external public outside of academia, existing research identifies a number of barriers that inhibit efforts related to these processes. While much attention in the research literature has been given to barriers related to knowledge transfer and commercialisation, the field of knowledge valorisation suffers from a lack of comprehensive recognition of its specific challenges. In the context of knowledge transfer and commercialisation, the literature typically identifies two main categories of barriers influencing the adoption and success of related activities in scientific institutions: external barriers and internal barriers (Fig. 1).

External barriers include legal, economic, financial, relational and communication factors. Legal barriers, for instance, include issues surrounding intellectual property rights generated during R&D activity (Gilsing et al., 2011; D’Este & Perkmann, 2011; Czemiel-Grzybowska & Brzeziński, 2015). While disseminating knowledge through publications is essential for scientists, it may conflict with the need to maintain business confidentiality in enterprises.

Economic barriers, in turn, include the limited potential of enterprises, a lack of cooperation between business and universities, the high risks associated with investing in new technologies or restricted demand for new products (Garcia et al., 2019; Lopes & Lussuamo, 2021). Bruneel et al. (2010), Tartari et al. (2012) as well as O’Reilly and Cunningham (2017) have additionally identified financial barriers connected with low financial outlays invested in research and development, complicated mechanisms for achieving a high internal rate of return for investors, and the substantial costs required to implement large-scale projects.

One of the most frequently cited types of obstacles to commercialisation and knowledge transfer are relational barriers. They result from a lack of interest on the part of enterprises in acquiring technologies and practical solutions from the realm of academia, insufficiently developed intermediary infrastructure, and differing goals, interests, priorities, as well as cultural differences between the research and business sectors (Bjursell & Engstrom, 2019; De Wit-de Vries et al., 2019; O’Reilly & Cunningham, 2017). Relational challenges are often exacerbated by communication issues. Effective communication by knowledge valorisation units should facilitate to a two-way flow of information, ensuring that the capabilities of research units are presented in the context of the needs and expectations of businesses.

The other major category of barriers that influence knowledge commercialisation and directly relate to the functioning of scientific units consists of internal barriers, including formal, organisational, financial, information, competence-related, psychological and personal factors.

Among formal barriers, Bruneel et al. (2010) and Gilsing et al. (2011) identify the lack of internal legal regulations at universities, regulations hampering competitive activity on the part of universities, and the lack of long-term strategies and practical vision of commercialization in research units.

Organizational barriers, in turn, often stem from the organizational unpreparedness of research units to undertake activities in the area of commercialization and cooperation with partners, the lack of support units, the poor organization of technology transfer centres, a lack of close cooperation between universities, enterprises and local governments, an emphasis on teaching, excess responsibilities faced by academic researchers, bureaucracy and inflexibility in the university administrative system, and a lack of internal procedures related to knowledge commercialisation. Other organizational barriers include problems finding suitable partners, a lack of knowledge about companies seeking to acquire technology, or formal challenges related to publishing research results during the commercialisation process (D’Este & Perkmann, 2011; Epting et al., 2011; Namdarian & Naimi-Sadigh, 2018; O’Reilly & Cunningham, 2017).

Organisational barriers are often intertwined with information barriers, such as insufficient awareness of commercialization opportunities or the availability of funding (Ahmed et al., 2017). The absence of clear communication channels and guidance further limits researchers’ ability to navigate the commercialisation process effectively.

Internal financial barriers represent another critical challenge. These include a lack of initial capital within universities, especially for high-risk, early-stage projects, high investment costs, the limited profitability of some projects, and insufficient funding allocated to technology transfer at universities. Moreover, financial barriers are linked to high transactional costs of collaboration with industrial partners and a lack of financial incentives for scientists (Bruneel et al., 2010; Epting et al., 2011; Muscio et al., 2016; Tartari et al., 2012).

Competence, psychological and personal barriers are strictly connected with employees’ competences, attitudes and behaviours. The key competence-related barriers faced by researchers in the area of knowledge transfer processes are a lack of knowledge and skills in entrepreneurship, effective communication, and marketing the presentation of solutions, as well as insufficient awareness of the rules of intellectual property protection. The most important psychological barriers are poor self-esteem, a lack of motivation, negative attitude towards taking risks, negative reactions of the scientific community, a lack of support from the university authorities, the existing hierarchy of values and existing behavioural patterns. Some barriers are of a personal character and are the consequence of a lack of support from family, the researcher’s family situation, and excess responsibilities at both work and home (especially typical for female researchers) (Ahmed et al., 2017; D’Este & Perkmann, 2011; Perkmann et al., 2013; Rosa & Dawson, 2006).

D’Este et al. (2012), in a study concerning general barriers to innovative activities, additionally distinguish revealed barriers and deterring barriers to innovation. Revealed barriers are only perceived as barriers to innovation by organisations that already engage in innovative activities because they have experienced those barriers. In contrast, deterring barriers are mainly experienced by non-innovative organisations.

Building on this prior research on the barriers to knowledge commercialisation and transfer, the following research questions were formulated in the present study:

- What are the main barriers to knowledge valorisation?

- Are the barriers related to the valorisation of knowledge the same as those related to the commercialisation and transfer of knowledge?

3. Research methodology

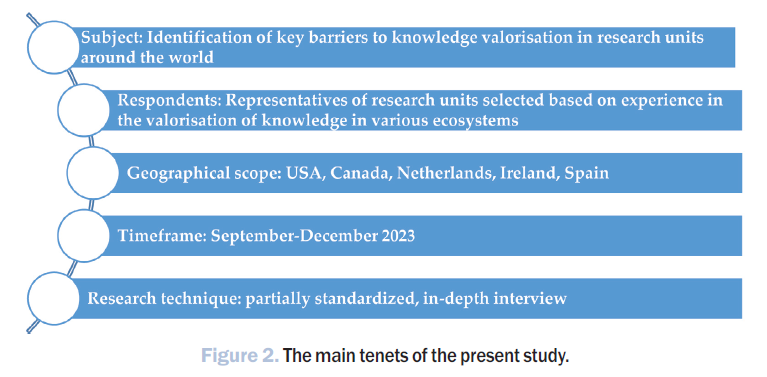

The present study was exploratory in nature, aiming to investigate the barriers to knowledge valorisation. Given the research goals and the formulated questions, a qualitative, interpretive approach was adopted. The primary research methodology was based on a partially standardized, in-depth interview, a qualitative research technique, with an interview protocol as the research tool. The decision to use in-depth interviews was influenced by both their advantages and limitations. Above all, this method makes it possible to obtain detailed data on the barriers of knowledge valorisation, enabling respondents to freely answer the questions (Glinka & Czakon, 2021).

The research units that participated in the study were deliberately selected based on their demonstrated expertise and extensive experience in knowledge valorisation processes, as well as their standings in widely recognized and respected international and national rankings. Efforts were made to ensure that regional diversity was maintained, while also incorporating a wide variety of institutions differing in size, institutional status, and primary research areas to provide a comprehensive and balanced representation. Moreover, the inclusion of a university in the study was dependent on its explicit agreement to participate, which played a pivotal role in determining the final sample composition. Note that not all invited universities responded positively to the invitation, which further influenced the makeup of the research group.

Given these selection criteria (high standing in international and national rankings, demonstrated experience in knowledge valorisation and commercialisation, regional diversity of the universities, preserving a mix of university sizes, statuses, and research areas, consent to participate in the research), the following universities and institutions participated in the study:

- from Ireland: Dublin City University, Trinity College Dublin, Munster Technological University in Cork, University of Limerick;

- from the Netherlands: “Innovation Exchange Amsterdam” cooperating with Amsterdam UMC, Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam (VU), University of Amsterdam (UvA) and Amsterdam University of Applied Sciences (HvA);

- from Spain: University of Malaga, Loyola University;

- from Canada: University of Montréal, HEC Montréal, McGill University, Toronto Metropolitan University, York University – Toronto, Canada;

- from US: University of Chicago.

The study encompassed both current and past activities related to the valorisation of knowledge. The research itself was carried out from September 1 to December 15, 2023.

The respondents selected for the study were individuals directly responsible for overseeing and implementing knowledge valorisation activities within their respective research units. Their selection was deliberate, focusing on individuals with relevant expertise and authority in the field. All interviews were conducted in the respondents’ offices, creating a comfortable and familiar environment for the discussions. The interviews ranged in duration from one to three hours, with longer sessions occurring when multiple participants were involved. To ensure accuracy and reliability, all interviews were conducted in English, recorded with the respondents’ consent, and subsequently transcribed for analysis.

The respondents in the study were individuals responsible for knowledge valorisation activities at their respective research units. Their selection was deliberate. All interviews took place at the respondent’s office and lasted between one and three hours. Longer interviews took place when more than one person participated. The interviews were conducted in English. With the respondents’ consent, each interview was recorded and then transcribed.

The research material so obtained underwent rigorous qualitative analysis. Content analysis was used to interpret the respondents’ statements. The collected material was gathered, interpreted and conclusions were formulated, with individual findings supported by appropriate quotes from the interviews. Including quotations not only enhances the authenticity of the data but also provides insight into the respondents’ perspectives, ensuring that the findings are rooted in genuine and unaltered narratives.

4. Research results

The results indicate that barriers to knowledge valorisation stem from both external and internal factors. Among the most significant internal barriers identified by the participants were the lack of time and awareness of the need for commitment among researchers. Representatives from the University of Montreal pointed this out, stressing that: “It’s very important to make it clear at the beginning with the researcher to say it will [take time], you need to be at least, to spend some time on that. It’s not only one hour, you know, per month, which is not reasonable. So, if you want to have a real project in valorisation, you will need to invest time”. A similar opinion was expressed by respondents from McGill University, York University and Toronto Metropolitan University, who underlined the insufficient involvement of researchers, as well as by a representative of University of Malaga, who stated: “The researchers, well, they also have also a lot of things to attend to, because they have to get classes, they have to do research. They have to get the economic, administrative control of the projects… It’s difficult to convince the people inside the university”. A respondent from HEC Montreal similarly pointed out the lack of time of the researchers and the lack of understanding of the complexity of the valorisation process. He stressed that: “[For a] professor who works, I would say, not alone, but who is not part of a big team, with lots of resources, administrative resources to help them, it’s difficult for them to make time. So time, that would be the first [barrier]”. A similar opinion was expressed by the respondent from Loyola University in Spain who also highlighted the lack of competence in knowledge valorisation processes among scientists and who stated that: “Another thing is sometimes the lack of knowledge about them, about the possibilities of transfer and valorisation”.

Another barrier, as the York University respondent pointed out, is the lack of time and interest from PhD students and undergraduates who are part of research teams: “If you have a prof who is interested in [knowledge valorisation], but the student isn’t, there is disparity there, you find that, kind of, the team doesn’t work well when they don’t have the right personnel on board in the lab”.

Respondents from Munster Technological University in Cork saw a lack of leadership culture as the main barrier to valorising knowledge, as their academics promote a traditional approach, they just want to teach and do research. So there are no role models when it comes to encouraging them to get involved. A similar view was expressed by representatives from the University of Limerick, who indicated that they had great difficulty in attracting staff who were capable and willing to implement knowledge valorisation processes.

A respondent from the University of Chicago singled out, among the most important barriers, the lack of interest of some researchers in valorising knowledge: “We do have, you know, faculty who may just not be interested in … and they just want to, you know, publish. And they don’t, you know, come into our process.”

According to respondents from the Université de Montrèal, there is a financial barrier in case of early-stage projects. This respondent stated that: “We’re working on that, but at the really risky level, the really early stage, they [scientists] realise it’s not easy to get funding”. Similar opinions were expressed by respondents from McGill University and York University. They underlined that one of the most important barriers related to knowledge valorisation is the early stage of the technology and difficulty in obtaining funding for its development (especially when the technology is high risk and immature). A similar position was presented by a respondent from the University of Chicago: “We feel that we need to get, you know, more money, more dollars into our processes in order to help faculty do the early work … Sometimes faculty will need to do, you know, some prototyping, or they need to do more data analysis and collect more data, but they just don’t have the funding through their grants to be able to do it. And so we’re looking at getting dollars, you know, for them so that they can move their idea, you know, further along. So, that’s sort of an obstacle”.

The respondent from HEC Montreal pointed to the small amount of funding allocated to social innovation. As he highlighted: “In social innovation, not really a lot of grants for this, you know? Part of the problem is that I think it’s kind of new. It’s a new word, … it’s very hard for the government… to assess the impact.” The lack of resources for valorisation activities is the most important barrier according to a York University respondent: “There is a lot of funding at the university for doing research, but when it comes to [knowledge valorisation], there is not a lot of government sources”. Among the barriers related to the valorisation of knowledge, the IXA representative also pointed primarily to financial constraints.

Among the main barriers, the respondent from HEC Montreal also cited pressure to make quick decisions from partners and administrative barriers related to contract preparation or a lack of administrative staff. He said: “I try to communicate the best I can, but sometimes a partner doesn’t understand. They don’t understand why it takes me like three weeks to send a contract”. In the opinion of the York University respondent, this is a consequence of too few staff at the university dedicated to supporting the area of knowledge valorisation and, as the respondent pointed out, the business side requires a lot of time and commitment. In addition, there is a shortage of specialists at the university who are able to properly assess the valorisation potential in the different disciplines and who have the right network through which they are able to find a partner.

According to respondents from Trinity College, complicated legal procedures and administrative barriers are a big problem. As one respondent pointed out: “Whenever we collaborate with industry, we have to be very careful not to help the company directly, because that would be anti-competitive, and this is a major problem. Another is bureaucracy, administration and collecting physical evidence of confirmation. The university is a big organisation and the bureaucratic and decision-making system is growing. In addition, new regulations are emerging”. Respondents from the Université de Montrèal also underlined that the time-consuming nature of the process is a barrier for research units’ partners. A similar opinion was expressed by representatives of McGill University, who stated that: “The process is too complicated – very, very common. It’s too hard to do this”.

According to respondents from McGill University, another barrier for partners is the lack of regulation at the national level, resulting in a need to create personalised contracts. When this happens, partners are often overly demanding about clauses in contracts. One respondent noted: “We face a lot of objections on some of the licensing terms”

Canadian universities’ representatives also highlighted cultural issues and the lack of willingness on the part of both Canadian researchers and representatives of different organisations to take risks. In their view, there is still an insufficient culture and popularisation of knowledge valorisation at research units: “Because I think in order to perform as a professor, teaching, researching, the most important things, so I understand why it’s like, it’s more than enough for one person to deal with. I think, so I understand why valorisation is not as much part of the culture”.

Therefore, as Dublin City University representatives stressed, researchers first and foremost want to publish. Consequently they often prioritise this over valorisation projects: “And I suppose internally, the biggest problem is the perception among PIs, researchers that is either commercialise or publish. It’s one or the other. And just convincing them, you can actually do both. So, that’s almost, that’s probably the biggest reason they don’t come to us if they, even when they think they should. It’s because they think we will stop the publication because the researchers in the university are interested to publish. That’s a problem”.

Another barrier, in the opinion of a respondent from Toronto Metropolitan University, is communication and the language used by researchers. As this respondent pointed out: “Research is understood very differently by a company than what a researcher would say ‘this is research’. So, if you look at the definitions or if you would ask for definitions, it would probably differ quite substantially. So, getting people to understand takes some effort, takes some time.” Internal communication is a significant barrier also in the opinion of the York University respondent. The innovation office is not aware of many initiatives or partnerships taking place at the departmental or institute level. As a result, many networks are created and some opportunities remain untapped. In his opinion, there should be one central location, a base where all the information on the solutions implemented as part of the knowledge valorisation process is recorded.

A new barrier that has emerged in the context of knowledge valorisation is the problem of measuring its impact. Universities are able to measure economic impact using quantitative methods, whereas measuring social impact is much more difficult. Among the primary measures of knowledge valorisation, all universities use the classic quantitative measurement of impact – expressed through the number of patents, the number of licences, the number of invention/software disclosures, the number of agreements with business, the value of revenue, or the number of research collaboration agreements with non-commercial entities. However, all respondents confirmed that social impact measures are lacking. Respondents from University of Montreal stressed that they are still working on how to measure social impact, which they believe is very difficult. Respondents indicated that they are trying to do more by focusing on impact, such as the number of jobs created from start-ups. In the case of social impact, measurement in the view of one respondent: “is about telling a story, but it’s really just a qualitative description, not a quantitative one”.

When it came to measuring social impact, a respondent from HEC Montreal pointed to qualitative measurement as a solution: “contacting a few key partners, … and asking them how the innovations have changed them”. Also at Toronto Metropolitan University, one of the biggest barriers is considered to be the measurement of knowledge valorisation. The respondent declared that the university tries to find indicators at each stage: “I don’t know of a general metric that would cover all the social impact… So, there are lots of organisations that try to kind of integrate social impact metrics into more standard corporate economic accounting, but I’m not sure if anyone has actually found a way that the majority of organisations applies.”

5. Discussion

Among the primary internal barriers influencing knowledge valorisation, respondents especially highlighted internal social factors. This finding conforms with studies by Ahmed et al. (2017), d’Este and Perkmann (2011) and Perkmann et al. (2013), which emphasize competence, psychological and personal factors as key barriers to knowledge commercialisation and transfer. Like the observations made by the university representatives in the present study, those researchers noted that a lack of motivation and entrenched behavioural patterns can significantly hinder the processes of knowledge commercialisation and transfer. A shortage of time, mentioned by representatives of different universities in Canada and Spain, was also underlined by Rosa and Dawson (2006), especially in the case of women science entrepreneurs, who often face additional challenges in balancing work, home life, and networks.

Among personal factors, the lack of commitment among scientists emerged as a frequently cited barrier. These findings corroborate the conclusions of Czemiel-Grzybowska and Brzeziński (2015), who identified individual researcher characteristics as critical determinants of academic engagement.

The study also confirmed the negative impact of internal financial barriers, particularly stemming from the lack of initial capital at the university, especially in case of high-risk, early-stage projects. Similar challenges were indicated previously by Bruneel et al. (2010), Epting et al. (2011), Muscio et al. (2016), or Tartari et al. (2012) in the case of knowledge commercialisation.

Internal organisational barriers were mentioned less frequently by respondents, mainly in context of internal communication issues. Consequently, in this respect our findings did not align with those of d’Este and Perkmann (2011), Epting et al. (2011), Namdarian and Naimi-Sadigh (2018) or O’Reilly and Cunningham (2017), who reported a strong influence of internal organisational problems on knowledge commercialisation and transfer processes. According to O’Reilly and Cunningham, scientists often express frustration in their dealings with technology transfer offices. This sentiment was not confirmed by our results, likely due to the fact that our respondents were themselves often managers of such offices.

Our research results also did not confirm the presence of internal formal barriers identified previously by Bruneel et al. (2010) and Gilsing et al. (2011). This may indicate progress in the systematic development of structures and procedures responsible for knowledge transfer at universities, leading to the reduction of these barriers.

Among external barriers, previous research has highlighted financial, relational and communication factors. In this study, respondents confirmed some problems with the

legal regulations, for example agreements, and financial barriers connected with the insufficient funding for valorisation projects. This meshes well with the previous findings of Bruneel et al. (2010), Tartari et al. (2012) as well as O’Reilly and Cunningham (2017) in the area of knowledge transfer. Additionally, the lack of industry investment in basic research and the high costs associated with commercializing research findings were indicated as barriers to commercialisation activities also by Namdarian and Naimi-Sadigh (2018).

Our study likewise confirmed the presence of deterring barriers that are mainly experienced by researchers without experience, as d’Este et al. (2012) indicated in their study concerning general barriers to innovative activities.

A novel barrier identified in this study is relates to the qualitative measurement of the social impact of knowledge valorisation initiatives. Since knowledge valorisation encompasses numerous dimensions, an exclusive focus on quantitative economic and technological metrics overlooks other important impacts of research, such as the impact of knowledge on the general public and societal welfare. Furthermore, the lack of indicators for measuring social impact decreases the perceived value of knowledge valorisation, concentrating only on societal value. The absence of strategies to promote the society impact of knowledge on society – partially connected with the lack of tools to measure these factors – was indicated previously by van de Burgwal et al. (2019).

6. Conclusions

The present study sought to answer the challenging question of identifying the key barriers of knowledge valorisation, which relates to the use of scientific knowledge in practice – whether by creating a product, system or process, or developing a new policy. Knowledge valorisation is essential for driving innovation, which in turn fuels economic growth and prosperity. However, when formal, financial, organisational, relational or psychological barriers impede effective knowledge valorisation, it not only affects technological and economic development but also has broader societal implications.

Our findings indicate that internal barriers, especially those related to competence, psychological and personal factors, were most often identified by representatives of the studied universities. Financial barriers, both internal and external, also emerged as significant obstacles. Additionally, we identified a new important barrier: the lack of metrics to measure social impact.

These results contribute to a deeper understanding of the barriers to knowledge valorisation and allow for comparison with the barriers that have been identified for the commercialisation and valorisation of knowledge. In this regard, our results reveal that the most relevant barriers of knowledge valorisation include researchers’ lack of time, awareness and engagement, as well as the lack of financial support for projects aimed at valorising knowledge. A barrier that does not appear in the context of commercialisation and knowledge transfer, but is crucial when it comes to its valorisation, is the lack of metrics to measure social impact. This limitation complicates the assessment of ongoing and potential projects and reduces the chances of attracting interest and funding from external partners.

From a practical perspective, in terms of managerial implications, our results have implications for scientists, research managers and universities authorities. Understanding the main barriers may help scientists and research managers better prepare to face different challenges during the process of knowledge valorisation. Our results may also be useful for managers responsible for knowledge valorisation processes at universities, highlighting ways to overcome barriers and to enhance cooperation and impact creation among scientists and external partners. Moreover, university administrators and policymakers can benefit from these findings to develop solutions, adopt best practices, and establish clear guidelines.

From a social perspective, our results are relevant for policymakers at regional, national and European levels. Scientific units have to understand their role in shaping broader societal dynamics and ensure that their knowledge valorisation efforts contribute positively to social welfare and economic development. The results of the present study shed light on the challenges hindering effective knowledge valorisation by scientific units and indicate the main barriers that must be addressed. By emphasizing strategies that heavily favour technological advancements or highly specialized expertise, knowledge valorisation can drive not only on economic and technological development but also on the creation of value for society.

Finally, our study has a few limitations that open up further directions for future research. Firstly, the qualitative nature of our research and the relatively small sample size suggest the need for further studies with a larger, more representative sample. Secondly, this study focused on chosen countries, so an interesting avenue for further research could explore a comparative analysis of knowledge valorisation barriers across different countries.

References

Ahmed, U., Umrani, W. A., Pahi, M. H., & Shah, S. M. M. (2017). Engaging Ph.D. students: Investigating the role of supervisor support and psychological capital in a mediated model. Iranian Journal of Management Studies, 10(2), 283–306.

Baycan, T., Stough, R. R. (2013). Bridging Knowledge to Commercialization: The Good, the Bad, and the Challenging. The Annals of Regional Science, 50(2), 367–405.

Benneworth, P., Jongbloed, B.W. (2010). Who matters to universities? A stakeholder perspective on humanities, arts and social sciences valorization. Higher Education, 59(5), 567–588.

Beyer, K. (2022). Barriers to innovative activity of enterprises in the sustain development in times of crisis. Procedia Computer Science, 207, 3140–3148.

Bjursell, C., & Engstrom, A. (2019). A Lewinian approach to managing barriers to university–industry collaboration. Higher Education Policy, 32(1), 129–148.

Bruneel, J., D’Este, P., & Salter, A. (2010). Investigating the factors that diminish the barriers to university industry collaboration. Research Policy, 39(7), 858–868.

Cain, K., Shore, K., Weston, C. & Sanders, C. (2019). Knowledge Mobilization as a Tool of Institutional Governance: Exploring Academics’ Perceptions of “Going Public”. Canadian Journal of Higher Education, 48(2), 39–54

Czemiel-Grzybowska, W., Brzeziński, S. (2015). Selected barriers management of commercialization in the international university research. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 12, 59–68.

D’Este, P., Iammarino, S., Savona, M., & Von Tunzelmann, N. (2012). What Hampers Innovation? Revealed Barriers Versus Deterring Barriers. Research Policy, 41, 482–488.

D’Este, P., Perkmann, M. (2011). Why do academics engage with industry? The entrepreneurial university and individual motivations. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 36(3), 316–339.

De Silva, P. U. K., Vance, C. K. (2017). Assessing the societal impact of scientific research. In P. U. K. De Silva, C. K. Vance (Ed.), Scientific Scholarly Communication (117-132). Springer.

De Wit-de Vries, E., Dolfsma, W. A., van der Windt, H. J., & Gerkema, M. P. (2019). Knowledge transfer in university–industry research partnerships: A review. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(4), 1236–1255.

Derrick, G. E., Bryant, C. (2013). The Role of Research Incentives in Medical Research Organisations. R&D Management, 43(1), 75–86.

Epting, T., Gatling, K., & Zimmer, J. (2011). What are the most common obstacles to the successful commercialization of research? SML Perspectives, 1(2), 9–13.

European Council (2022). The Council Recommendation (EU) 2022/2415 of 2 December 2022 on the guiding principles for knowledge valorisation.

European Commission (2023). The Commission Recommendation (EU) 2023/499 of 1 March 2023 on a Code of Practice on the management of intellectual assets for knowledge valorisation in the European Research Area.

Garcia, R., Araujo, V., Mascarini, S., Santos, E. G., & Costa, A. R. (2019). How the benefits, results and barriers of collaboration affect university engagement with industry. Science and Public Policy, 46(3), 347–357.

Gilsing, V., Bekkers, R., Bodas-Freitas, I.-M., & van der Steen, M. (2011). Differences in technology transfer between science-based and development-based industries: Transfer mechanisms and barriers. Technovation, 31(12), 638–647.

Glinka, B., Czakon, W. (2021). Podstawy badań jakościowych [Fundametals of Qualitative Research]. PWE, Warszawa. [in Polish].

Grębosz-Krawczyk, M., Milczarek, S. (2020). Communication Between Scientific Units and Companies in the Context of Their Cooperation. In A. Zakrzewska-Bielawska & I. Staniec (ed.), Contemporary Challenges in Cooperation and Coopetition in the Age of Industry 4.0 (191–202), Springer.

Hladchenko, M. (2016). Knowledge valorisation: A route of knowledge that ends in surplus value (an example of the Netherlands). International Journal of Educational Management, 30(5), 668–678.

Jacobsson, S., Perez Vico, E. (2010). Towards a Systemic Framework for Capturing and Explaining the Effects of Academic R&D. Technology Analysis & Strategic Management, 22(7), 765–87.

Lopes, J., Lussuamo, J. (2021). Barriers to university-industry cooperation in a developing region. Journal of the Knowledge Economy, 12(3), 1019–1035.

Namdarian, L., Naimi-Sadigh, A. (2018). Towards an understanding of the commercialization drivers of research findings in Iran. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 10(4), 389–399.

O’Reilly, P., Cunningham, J.A. (2017). Enablers and barriers to university technology transfer engagements with small- and medium-sized enterprises: perspectives of Principal Investigators. Small Enterprise Research, 24(3), 274–289.

Perkmann, M., Tartari, V., McKelvey, M., Autio, E., Broström, A., D’Este, P., Fini, R., Geuna, A., Grimaldi, R., Hughes, A., Kabel, S., Kitson, M., Llerena, P., Salter, A., & Sobrero, M. (2013). Academic Engagement and Commercialisation: A Review of the Literature on University–Industry Relations. Research Policy, 42(2), 423–442.

Rosa, P., Dawson, A. (2006). Gender and the Commercialization of University Science: Academic Founders of Spinout Companies. Entrepreneurship and Regional Development, 18(4), 341–66.

Salehi, F., Shapira, P., & Zolkiewski, J. (2022). Commercialization networks in emerging technologies: the case of UK nanotechnology small and midsize enterprises. The Journal of Technology Transfer, published 19.01.2022, 1–29.

Tartari, V., Salter, A., & D’Este, P. (2012). Crossing the Rubicon: Exploring the factors that shape academics’ perceptions of the barriers to working with industry. Cambridge Journal of Economics, 36(3), 655–677.

van de Burgwal, L. H. M., Dias, A., & Claassen, E. (2019a). Incentives for Knowledge Valorisation: A European Benchmark. The Journal of Technology Transfer, 44(1), 1–20.