- eISSN 2353-8414

- Phone.: +48 22 846 00 11 ext. 249

- E-mail: minib@ilot.lukasiewicz.gov.pl

Employees of the future: Expected competences at the higher education level

Dobrosława Mruk-Tomczak*1, Ewa Jerzyk2

1Poznań University of Economics and Business, Department of Product Marketing

2Poznań University of Economics and Business, Department of Marketing Strategies

*1E-mail: dobroslawa.mruk-tomczak@ue.poznan.pl

ORCID: 0000-0002-4548-8260

2E-mail: ewa.jerzyk@ue.poznan.pl

ORCID: 0000-0001-8474-3570

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0006

Abstract:

Given the changing nature of the modern economy, technological advances and increasing globalization, labor markets are presenting university graduates with new challenges in terms of the competences expected of them. The aim of this article is to evaluate and forecast the future of labor market demands in relation to the competences of future employees. A comprehensive analysis of these expectations is presented, drawing on findings from the desk research method, further supplemented with a qualitative study. The discussion focuses on identifying key competences that employers are looking for in today’s business environment and the competences that will be necessary in the long term. The paper contributes to the ongoing debate on the transformation of curricula in higher education, especially in relation to business schools, emphasizing the need to continually monitor market expectations and make necessary adjustments to curricula. The conclusions from this study are intended to serve as a source of inspiration for decision-makers responsible for educational programs at universities, especially those with a business profile, and other stakeholders aiming to bridge the gap between the academic world and the dynamically changing labor market.

MINIB, 2024, Vol. 51, Issue 1

DOI: 10.2478/minib-2024-0006

P. 117-147

Published 29 March 2024

Employees of the future: Expected competences at the higher education level

Introduction

One of the important issues related to higher education is how the role of universities in the modern world is to be understood. An essential task of higher education institutions is to prepare specialists with competences that correspond well to employer expectations. The challenge facing the educational system, however, is to curate their curricula so as to teach competencies that not only meet current market demands, but will also remain relevant in a future marked by uncertainty. This is because ongoing socio-economic transformations induced by the fourth industrial revolution – where digitalization, automation, and globalization play the dominating role – in tandem with the diversity of values, cultures, and customs, demand a reevaluation of the competences necessary for both present and future employees. It is therefore imperative for both Polish and foreign universities to aim for better alignment between their curricula and the competency requirements of businesses and institutions.

The mismatch between competences taught by universities and the needs of employers translates into difficulties in finding suitable candidates for employment – approximately 33% of companies in Poland, for instance, report disparities between the desired competences and those possessed by job candidates. This issue is particularly emphasized in the services sector (where one in two companies is affected), as well as in medium-sized (44%) and large (33%) enterprises (Gi Group Holding Polska, 2023). Furthermore, research findings (Dąbkowska et al., 2022) indicate that this mismatch serves as a barrier to the growth of one in every three companies.

Universities and other institutions providing vocational education services face challenges in addressing the demands of the labor market. This is particularly evident from the perspective of state-owned institutions, following traditional education models, which require more time to effectively develop and implement new or modified programs that respond to evolving labor market needs . This sluggishness, sometimes further compounded by the bureaucratic hurdles inherent in state educational institutions, often opens up opportunities for alternative education providers, such as e-learning platforms, to fill the gap with flexible and widely accessible training options catered to specific market needs. The changing dynamics pose a threat to the long-standing supremacy of universities in credentialing highly qualified professionals, prompting a reimagining of the corporate education landscape. Beyond their rigid program-development procedures, other factors also deserve mention, such as inadequate state funding for higher education, the pauperization of the academic environment, and constraints in adopting new technologies, all of which determine the functioning of universities in shaping useful competences.

The objective of this article is to diagnose the current and future requirements of the labor market regarding employee competences, including those of graduates from business universities. Based on an analysis of secondary and primary data, we strive to infer the desired directions for competence development within universities. Given the relatively limited engagement of the latter sources, this article is of an exploratory nature, providing a general overview of anticipated labor market needs in the near future. Nevertheless, we believe that these insights will prove useful in designing and adapting business education programs facilitating the acquisition of valuable competences by students. Universities offering such competences will strengthen their competitive position, while businesses will be able to more successfully execute their strategies.

Nature and Types of Competences

The meaning of the term “competence” has evolved over time. Initially, it referred to a narrow concept – the formal authority to handle specific matters on behalf of an organization and to make decisions within a defined scope. This understanding later expanded to encompass the range of powers, duties, and responsibilities assigned to an employee’s organizational position. In 1973, McClelland associated competence with education. Boyatzis, regarded by many researchers as the pioneer of integrating the concept of competence into the field of human resource management (Sidor-Rządkowska, 2008), defined it in 1982 as “the potential existing in man, leading to such behavior that contributes to meeting the requirements of a given workplace within the parameters of the organization’s environment, which in turn provides the desired results” (Oleksyn, 2006). In the 1980s, the notion of competence was linked with the professional realm, particularly with human resources development, while in the 1990s, it came to be associated with the learning paradigm. A report to the National Institute of Education in the United States defines competence as “a fundamental characteristic of an individual that results in effective and/or excellent performance at work”.

Competence is perceived as a general ability, rooted in knowledge, experience, values, and inclinations, that a person has developed as a result of involvement in educational practices (Hutmacher, 1997). Competence cannot be reduced to knowledge based on facts or routine; being competent is not always equivalent to having knowledge or cultural awareness. In the broadest sense, competence is understood as encompassing knowledge, skills, attitudes and values, whereas in a more pragmatic understanding, as the indispensable prerequisites for meeting complex requirements, making decisions or performing work.

In the 21st century, the understanding of the concept of “competence” increasingly emphasizes independence and responsibility in the performance of tasks by employees, conscious engagement in work, and the associated accountability for its execution, in line with mutually agreed standards . When reviewing different approaches to this concept, it should be borne in mind that competences and their scope are in each case relevant to specific individuals working within a specific enterprise. Hence, we should acknowledge Wawrzyniak’s view that “an approach to managing the human factor within an organization based solely on formal qualifications and experience measured by seniority is not sufficient at the current stage of organizational development. The particular significance (of this factor) for the organization is associated with competences, understood as the knowledge, skills, motivation, attitudes, and behavior of employees.” These narrower and broader approaches to the concept of competence do not fully resolve the challenge of defining the term, but instead indicate the existence of varying aspects of the subject in question.

In this article we embrace a comprehensive interpretation of competences, following Le Boterf in defining it as the individual’s capacity to execute tasks by mobilizing appropriate resources (skills, knowledge, know-how, behaviors, and attitudes) among those previously acquired through education or prior experiences (Lamri, 2019). Furthermore, we assume that competences yield outcomes consistent with the strategic intentions of the company.

The existing literature on the subject presents various categorizations of competences, with authors dividing them up according to the characteristics they possess and functions they perform (Oleksyn, 2006; Moczydłowska, 2008; Rostkowski, 2002). Competences are commonly categorized into four main types: professional competences (primarily relating to job- related knowledge and skills), methodological competences (problem-solving and decision-making skills), social competences (cooperative and communicative skills), and personal competencies (social values, motivations, and attitudes). Lamari (2021), in turn, introduces a somewhat different categorization of competences into technical, behavioral and motivational, cognitive and civic competences, with the latter pertaining to the world and the position of the individual.

Another type of classification scheme differentiates between key competences and specific competences. According to Oleksyn (2006), key competences hold significance for the company, the job and the individual employee, as from the organization’s point of view they represent what the organization excels at, and considering the job they are crucial for performing tasks and duties within a job role. The key competences possessed by employees relate to the employees themselves, encompassing their distinguishing traits. Specific competences, on the other hand, pertain to employees’ features that are indispensable and characteristic for a particular position.

Sidor-Rządkowska (2008), in turn, argues that of the numerous potential classifications, it is most useful from the perspective of company practice to divide competences into company-related (corporate) competences that are common to employees of a given company, professional (vocational) competences that are closely related to the type of work performed, and social competences that are related to the need to establish and maintain contacts with other people.

The increasingly prevalent dichotomy between hard vs soft skills is perhaps the most straightforward classification of competences, adopted across various industries, regardless of their specific nature. Hard skills relate to specific theoretical knowledge and the ability to apply various methods, techniques, tools, procedures, or processes, usually stemming from the acquired education. Soft skills, on the other hand, mainly encompass interpersonal skills, individual predispositions, behavior, and the manner of cooperation with others (Oleksyn, 2011).

The overview provided here of various competence classifications captures only a fraction of the discourse within the academic literature, representing the viewpoints of select scholars. The field is abundant with diverse frameworks and typologies of competences, each offering unique insights and categorizations. For the purposes of this study, competences will be categorized into three distinct groups: social, cognitive, digital, and technical competences (as distinguished by Włoch & Śledziewska, 2023). However, it is important to bear in mind certain inherent limitations of this approach.

Research Methodology

We began our study using the desk research method. In order to explore the research topics from diverse perspectives, this initial phase involved a thorough analysis of existing data, focusing on reviewing the latest available publications, reports, data and other secondary sources. This enabled us to obtain a comprehensive understanding of the future labor market and the anticipated competences expected of employees within it. Desk research may provide important guidance to educational institutions, helping them adapt to the evolving professional landscape.

In the initial stage of the analysis, a total of 47 sources were gathered, comprising 34 Polish-language and 13 English-language materials. Prior to reviewing the secondary data, three research questions were formulated to support the process of analyzing the collected materials, ensuring their relevance to achieving the research objectives:

- What criteria should be used to evaluate sources of information relevant to the labor market?

- What are the main changes and trends that are expected in the coming years in terms of employees’ professional competences?

- According to existing research and reports on the labor market, what are the key competences of the future?

Materials were selected based on their recency (published by 2017), reliability (including a clear description of the methodology for obtaining information, and the credibility and integrity of the author/institution), and relevance. In the selection stage, having analyzed the content of the materials in terms of information regarding requirements or expectations of the competences of future employees, we selected 16 items for the final analysis, including 11 in Polish and 5 in English. The selected reports were characterized by different research approaches, socio-demographic profiles, and time horizons. All of them, however, identified common areas of competence for employees of the future, perceived from different perspectives. Key pieces of information on expected competences were inventoried from these sources and compiled in Table 1 and Figure 1.

This preparatory work laid the groundwork for conducting our empirical primary research, aiming to gather opinions on future labor market competences, particularly from university graduates at the onset of their careers. Given the exploratory nature of the study, semi-structured individual interviews were used, allowing for a high degree of flexibility in question selection and scenario adaptation depending on the course of the conversation. This method facilitated the inclusion of additional questions, not provided for in the scenario, thereby allowing for deeper topic engagement (Mościchowska & Rogoś-Turek, 2019). Two perspectives were adopted for labor market competence analysis: a general perspective, which pertains to the entire economy at both national and European levels, and a sectoral perspective, which arises from the respondent’s industry of employment. A five-year horizon for assessing the labor market was adopted: the evaluation was requested for both the present and the perspective of the next five years. Based on this desk research study, competences were categorized into three main groups: cognitive, social, and technical-technological. These categories were then subjected to a detailed assessment over the two designated periods.

In the initial part of the interview, closed questions were posed to determine which specific questions should be asked next. Conversely, open questions were employed to elicit longer statements, thereby laying the foundation for drawing several insightful conclusions from this study. We inquired about which categories of competences are currently relevant and will be crucial in the future, what competences are lacking among university graduates, which ones will be needed on the labor market, and how business practices could shape the direction of competences taught at universities.

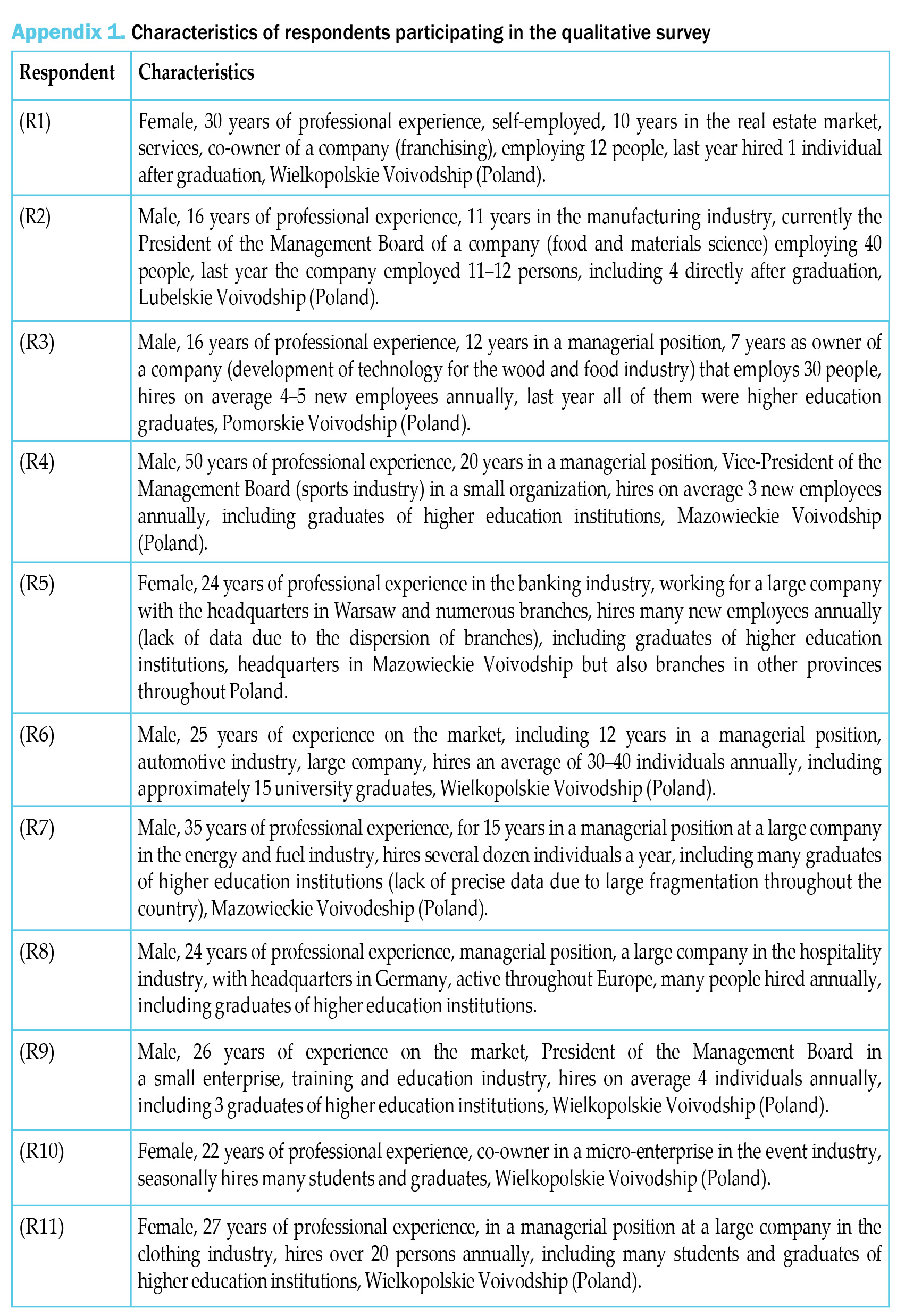

A total of eleven in-depth interviews were conducted, with the selection of participants aimed at capturing a broad spectrum of viewpoints. A detailed description of the research sample is given in the table provided in the Annex to this paper. To ensure inclusivity, all interviews were conducted remotely, either online or by phone, utilizing available automatic transcription methods (MsTeams, Microsoft Word, Zoom), with prior consent obtained from respondents. Interviews were conducted over a five-week period, typically lasting about an hour, scheduled in advance in order to minimize potential disruptions.

We individually familiarized ourselves with all transcripts of the interviews and independently outlined preliminary results. Subsequently, we discussed our findings collectively and formulated a list of synthesized conclusions.

Analysis of Research Results

The analysis of secondary data reveals several key challenge areas in the labor market concerning the expected competences and skills of future employees, particularly in an era characterized by dynamic social, economic and business-related changes. The source materials repeatedly emphasized the importance of cognitive and social competences. Practically all of the analyzed sources emphasized the importance of creative thinking (innovative thinking, unconventional thinking, innovation). The ability to solve problems, including complex problems, emerged as an equally important competence, linked with the frequently mentioned ability to make decisions and take responsibility for them. The vast majority of the reports highlighted the importance of interpersonal competences related to communication and negotiation, and teamwork, across various settings including stationary, virtual, and intercultural teams. Furthermore, dynamic changes in the work environment require the employees to be flexible, able to adapt quickly, and to learn continuously, as emphasized in many of the analyzed materials. Data from the analyzed reports showed that in a world dominated by technology, technical skills, alongside those related to the digital domain, are becoming increasingly essential.

Overall, the review of data in the initial stage of the study, employing the desk research method, clearly indicates that expectations regarding the competences of future employees revolve around the integration of diverse skills, encompassing interpersonal, cognitive, technical and digital abilities. Likewise, flexibility and readiness for continuous development can be key factors in securing a foothold in the future labor market. These findings are summarized in Figure 1 and Figure 2.

The analysis of selected sources facilitated precise planning and execution of the study in the form of semi-structured individual interviews. Consequently, the second stage of the research aimed to clarify the future needs of the labor market for employees and graduates of higher education institutions.

Responses from the respondents regarding the competences to be crucial for the economy in the next five years were quite similar to the conclusions drawn from the analysis of the reports. The respondents underlined the significance of all competences essential for the development of enterprises:

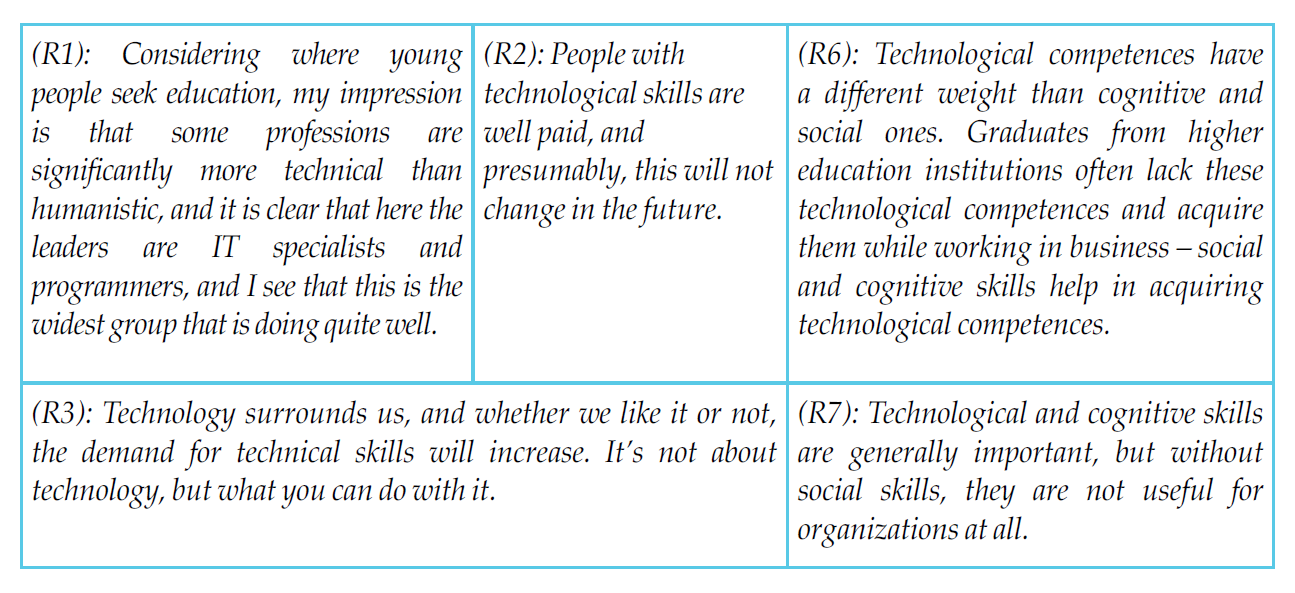

Respondents indicated that the modern labor market is looking for and strongly appreciates, in particular, technical and technological competences, which result from the need to adopt modern technologies in enterprises:

However, it is worth noting an opposing viewpoint, which, given the rapid, not entirely predictable evolution of artificial intelligence, may prove to be valid:

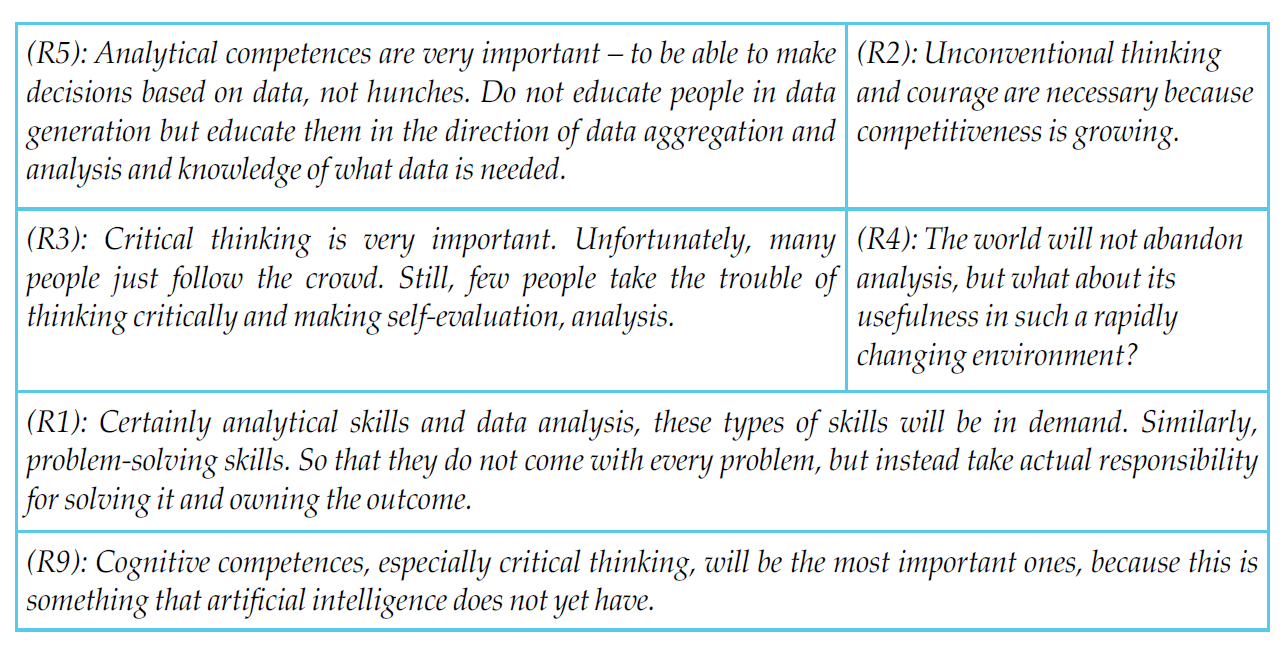

Respondents also pointed out that not every potential employee should possess expert-level technical and technological competences, because in business, it is possible to pursue different career paths with different requirements:

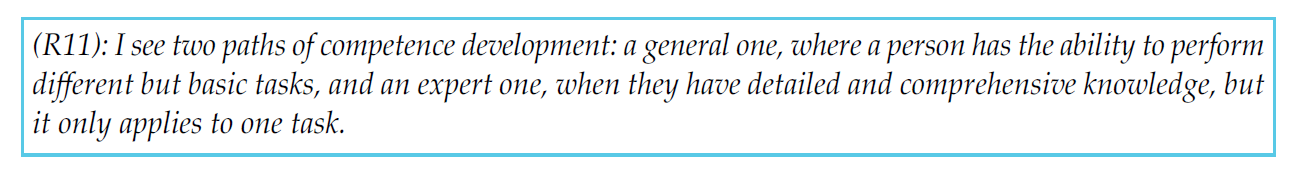

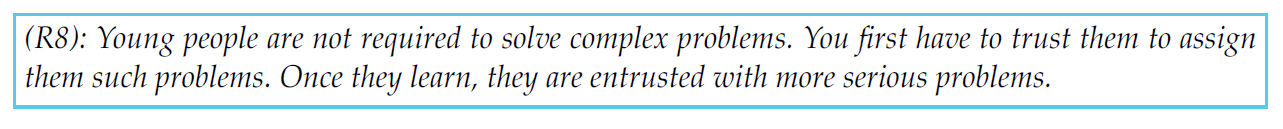

Analytical, critical and creative thinking skills were indicated among the cognitive skills that the labor market will demand in the next five years. The ability to search for and evaluate the quality of data, as well as the correct and independent interpretation of data were emphasized. Such opinions are not surprising, because already in 2020 the World Economic Forum recognized the ability to solve complex problems, critical thinking and creativity as the three most important competences of the future. However, as the respondents admit, graduates lack autonomy in solving problems:

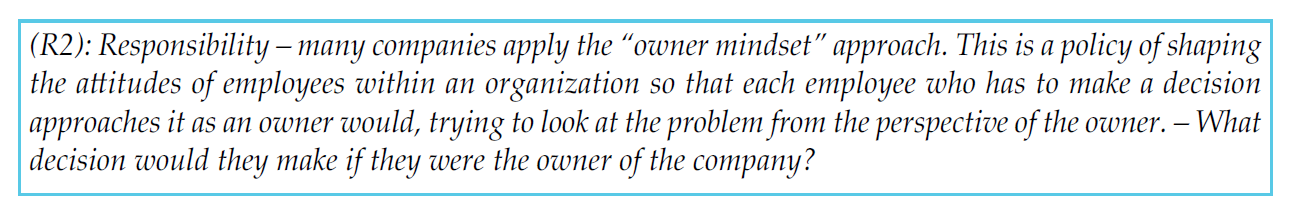

Respondents also noted the importance of responsibility for decisions made, although in regard to young employees who are at the early stages of their careers, they indicated that their expectations as employers are not excessive:

The respondents noticed that the increased expectations of employers toward the competence to assume responsibility may generate risks in the form of higher financial expectations:

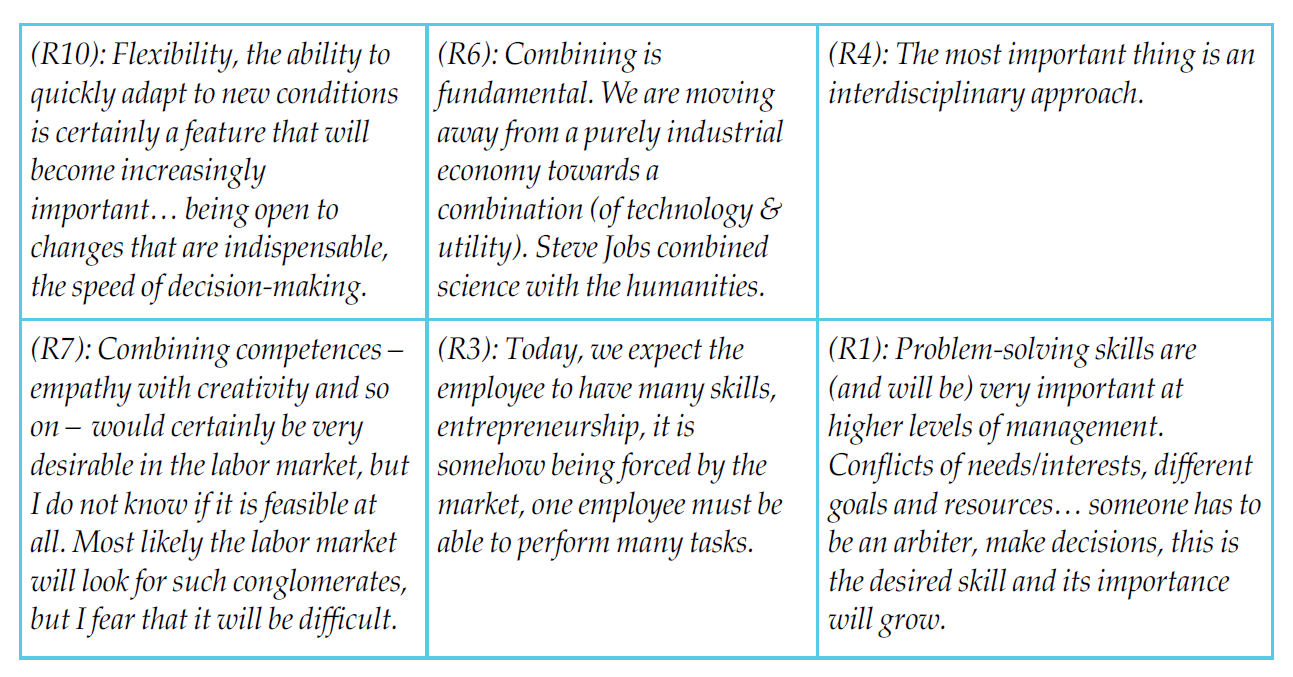

The opinions repeatedly referenced the pace of market development and the changes taking place, which were linked by the respondents to the growing demand for interdisciplinary competences from various domains. Dealing with current, complex problems requires broad knowledge, hence the need for more diverse education that combines, on the one hand, technological and engineering knowledge, and on the other hand, economic, psychological, and social expertise:

The modern market generates many opportunities, but also threats that can be predicted and mitigated. According to the respondents, graduates have limited competence to plan and perceive themselves, their careers in the context of an enterprise where certain processes occur. In their opinions, respondents expressed the need for competences of anticipation and a holistic approach to the implementation of tasks:

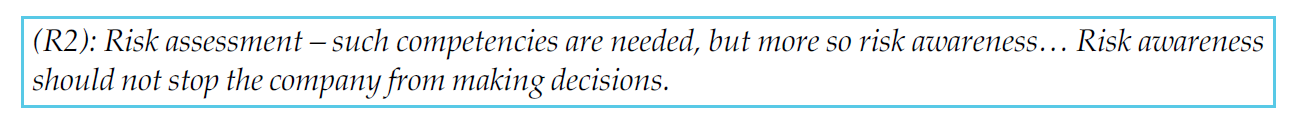

The respondents approached the skill of risk perception and assessment with caution, indicating that it is an important competence that will continue to be desired in the future, but it must not slow down decision-making processes or translate into the conservatism of a company that fails to capitalize on the emerging opportunities. The competence to anticipate in the world of turmoil and black swans constitutes a considerable value:

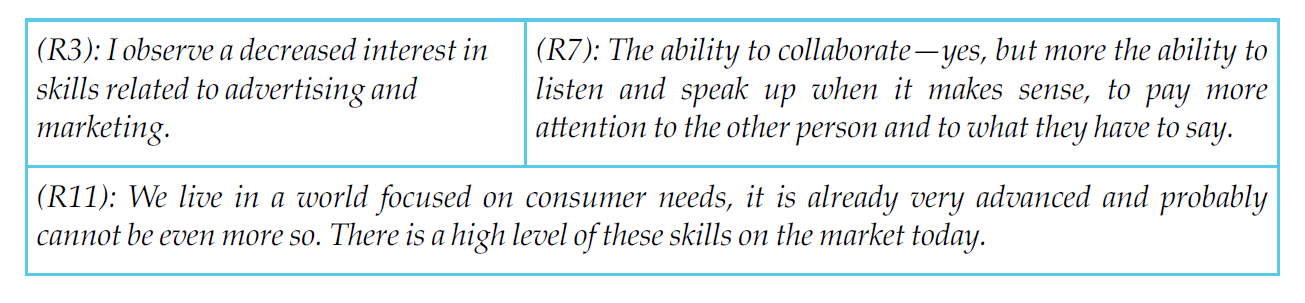

The topic of customer orientation and the ability to identify the client’s needs emerged in the interviews. Some respondents saw the value of this competence in the context of the market and quite advanced marketing skills (the needs of an external customer), while others identified it with empathy towards colleagues. According to the participants, monitoring the evolving customer needs, which is the essence of marketing skills, is currently at a high level and no changes in this respect should be expected. Several participants indicated the need to elevate the skills of empathic, attentive approach to internal clients. Cooperation with other employees must be based on openness and responsibility, while the lack of the ability to empathize with colleagues at work diminishes the effectiveness:

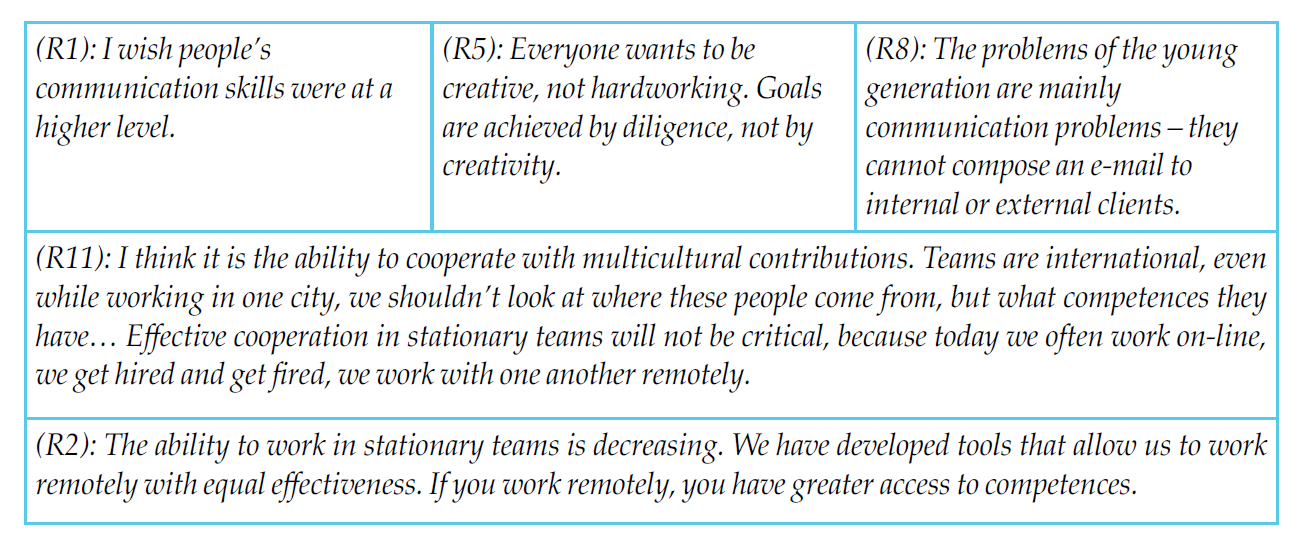

Both now and in the future, social skills will be important; the ability to communicate in virtual and multicultural teams, which was acquired intensively during the pandemic, was particularly appreciated among them. Basic competences such as diligence, reliability, listening, and mindfulness were also emphasized. The opinions presented suggest that the accelerated pace of technological progress does not entail the obsolescence of traditional (non-technical) competences:

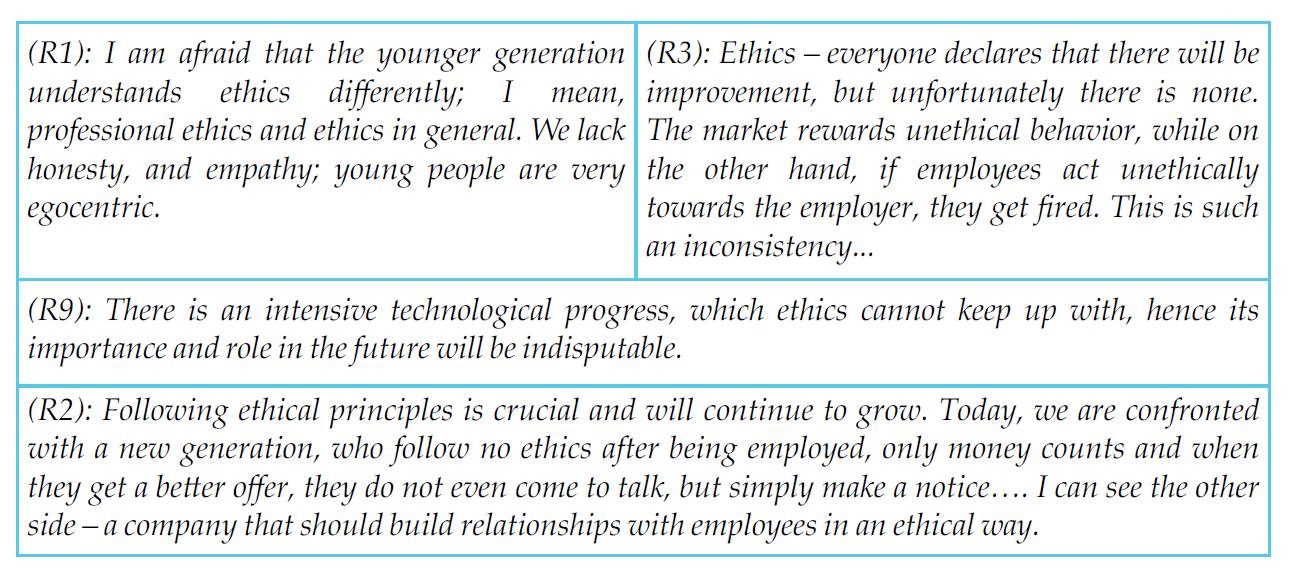

Respondents also pointed to ethics as an important trait of an employee, the significance of which will continue to grow. However, the opinions were rather normative, that is, they indicated how things should be. Attempting to analyze the genuine needs within this area of competence resulted in the rather gloomy conclusion that there are dual ethical standards: the first being the “employee’s conduct towards the market,” where unethical behavior may be tolerated if it benefits the company, and the second being the “employee’s conduct towards the company,” where any instances of unethical behavior are penalized. Respondents noted that there was no “commitment to duration” among young employees (Moczydłowska, 2021):

Respondents also shared their insights in the context of personal development, self-management and lifelong learning. The collected opinions highlight the importance of these skills, which still do not receive sufficient attention during education or in the workplace:

In addition to those mentioned so far, the competences sought in the future include skills related to presenting and implementing environmentally and socially friendly solutions. Currently, the market interest in such skills is still moderate, but according to the respondents, it is important that such skills be taught at universities. The trend of sustainable development and the circular economy will require new competences based on knowledge of the economic, social and environmental conditions of the market, skills of sustainable project management and a creative attitude towards social innovation. One of the most critical challenges facing businesses is the ESG business area. Increasing competition for “green talent” is evident – 74% of global employers are currently or planning to actively recruit candidates with “green skills” (ManpowerGroup 2023). The respondents expect that future graduates will be able to create solutions with environmental and social impact. However, they do not advocate for adding new subjects to the curricula, but rather see the necessity of enriching the educated competences with this new context:

In addition to those mentioned so far, the competences sought in the future include skills related to presenting and implementing environmentally and socially friendly solutions. Currently, the market interest in such skills is still moderate, but according to the respondents, it is important that such skills be taught at universities. The trend of sustainable development and the circular economy will require new competences based on knowledge of the economic, social and environmental conditions of the market, skills of sustainable project management and a creative attitude towards social innovation. One of the most critical challenges facing businesses is the ESG business area. Increasing competition for “green talent” is evident – 74% of global employers are currently or planning to actively recruit candidates with “green skills” (ManpowerGroup 2023). The respondents expect that future graduates will be able to create solutions with environmental and social impact. However, they do not advocate for adding new subjects to the curricula, but rather see the necessity of enriching the educated competences with this new context:

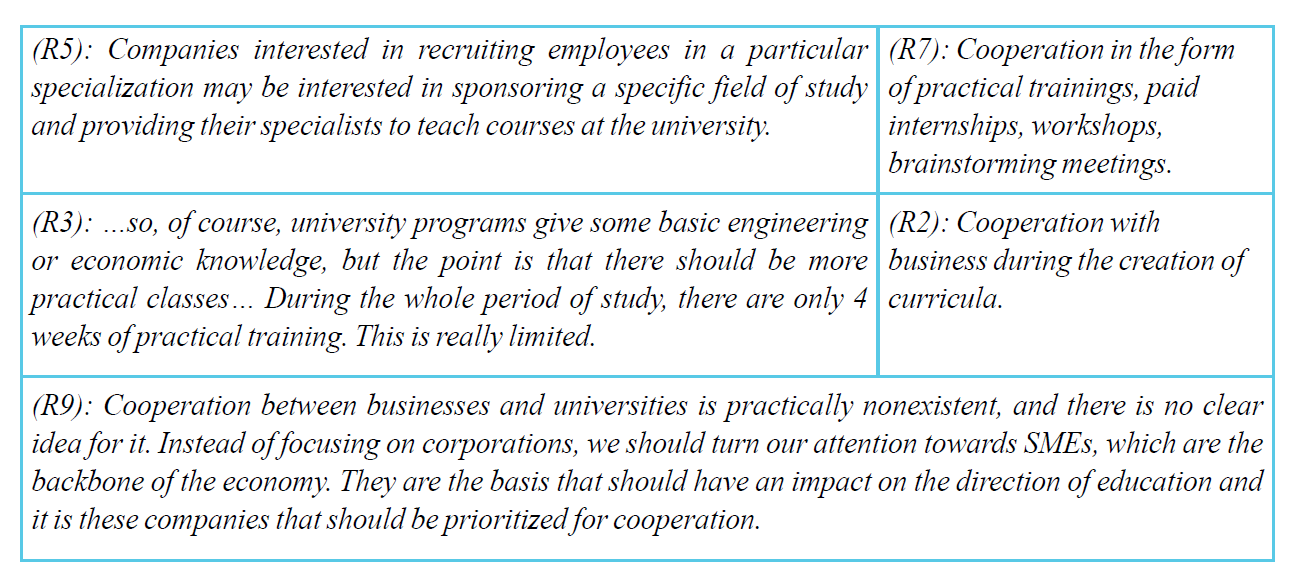

Deficiencies in the competences of university graduates relate primarily to project management, the ability to identify processes in business project management. The respondents indicate that graduates are able to perform partial analyzes but have a limited ability to think holistically. In this context, some have called for the enrichment of education in engineering fields with economic content and for the supplementation of economic disciplines with knowledge from other areas of science. Due to the shortage of certain specialists on the market, respondents advocate for greater openness of universities in terms of offered courses and for enriching curricula with content taught by practitioners:

Deficiencies in the competences of university graduates relate primarily to project management, the ability to identify processes in business project management. The respondents indicate that graduates are able to perform partial analyzes but have a limited ability to think holistically. In this context, some have called for the enrichment of education in engineering fields with economic content and for the supplementation of economic disciplines with knowledge from other areas of science. Due to the shortage of certain specialists on the market, respondents advocate for greater openness of universities in terms of offered courses and for enriching curricula with content taught by practitioners:

What is more, the conducted interviews reveal a rather specific outline of the competences of future graduates required by the labor market. The respondents expect further acceleration of market change, which will require flexible adaptation to changing situations and continuous improvement of skills. The new employees will enter the labor market knowing they cannot stop learning, the end of their university studies is simultaneously the beginning of their learning in other forms and training systems. Expectations regarding technical and technological competence will increase. It is anticipated that technologies will advance to the extent that not only knowledge of their use will be required, but also practical application skills in implementing advanced business solutions that will increase employees’ efficiency will be needed. The opinions of the respondents indicated the desire to acquire specific technological skills, but in a different form than as a few months of postgraduate studies. The respondents’ statements emphasized the need to include the aspect of sustainable development in future competences. The transition to a circular economy will result in a greater demand for the knowledge and skills to cope with such a transformation.

Conclusions

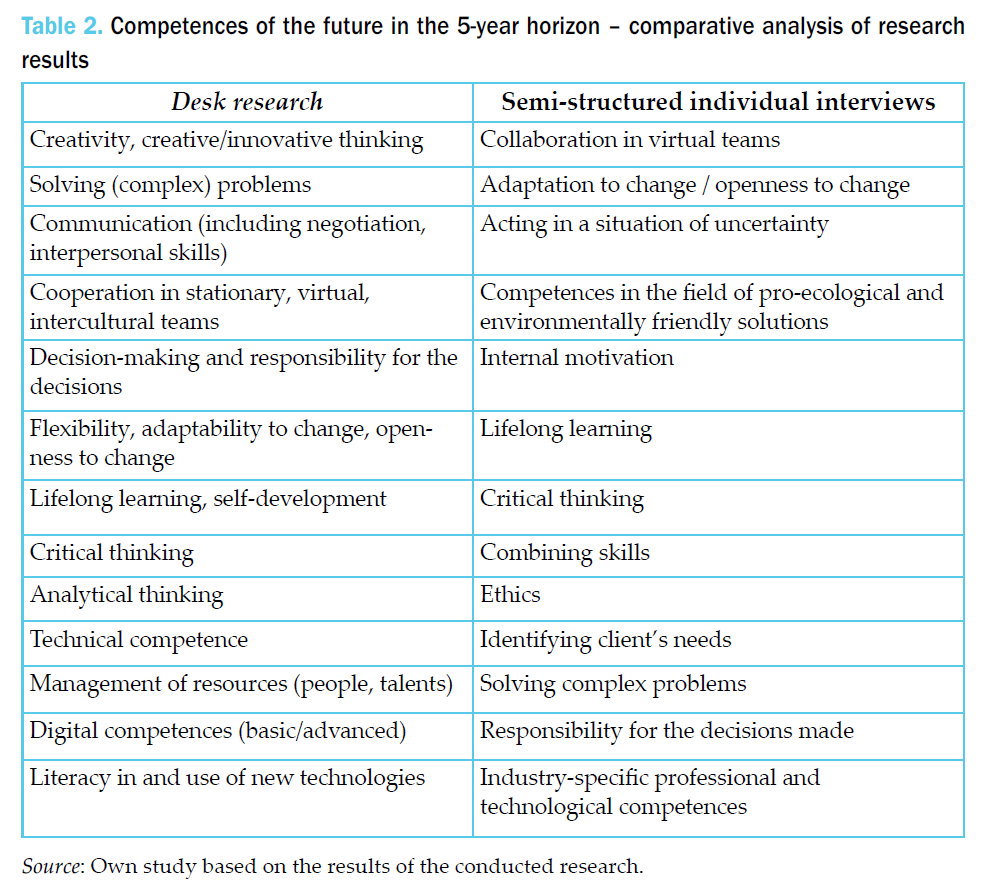

Our study, based on both desk research and in-depth interviews, has yielded a valuable compilation of competences of tomorrow, the thorough analysis of which can offer crucial guidance for educational institutions, in particular business universities, aiding them to adapt to the evolving professional landscape. Table 2 lists the most frequently indicated job competences, considering a 5-year perspective, based on both the desk research and in-depth interviews.

Our findings indicate that key competences for the future constitute a complex and multidimensional set, encompassing both soft and hard (technological) areas. Key competences will include the ability to adapt to change, flexibility, and openness to new challenges. Both lists point to the conviction that employees of the future must be versatile, having not only technical abilities but also interpersonal skills and being characterized by an ethical attitude. Consensus on the role and importance of lifelong learning and intrinsic motivation is evident in the results of both desk research and in-depth interviews. Similarly, critical thinking is crucial in both compilations. Juxtaposition of the results highlights the importance of creativity, innovative thinking and problem-solving skills in a dynamic business environment. Interpersonal competences, such as effective communication, negotiation, and collaboration are important in stationary work and increasingly significant while working in virtual and cross-cultural teams, which was especially emphasized in the interviews. In the face of emerging technologies, the research shows the importance of digital skills, managing new technologies and flexible approach to change in the digital environment. The results also demonstrate the need to focus on key competences that will be sought in the future on the labor market:

- solving complex problems, including those related to sustainable development

- enhanced analytical skills

- responsibility for the decisions made.

Effective cultivation of these skills requires adjustment of curricula and close collaboration between practitioners and universities.

Education systems struggle to respond to the new needs of the labor market. There are many factors that prevent rapid reactions from the higher education institutions in terms of shaping the competences of their graduates. The main external barriers to innovation in education programs are the lack of cooperation between academia and business practice and the mismatch between the pace of technological evolution and changes in educational institutions. The opinions of our respondents indicate a great need for cooperation between universities and practice in the field of designing curricula, conducting classes, practical trainings and internships. Active cooperation with business representatives and employers should be a priority. Universities should actively cooperate with representatives of employers, invite and engage them in designing educational programs, and what is more, adapt the content to real market needs. A lack of dialog between universities and businesses will lead to an increase in the gap between competences and labor market needs, which in turn will affect the growth of educational tourism and the search for valued competences abroad (educational tourism). From the perspective of the university, possible problems with the evaluation of the didactic process carried out in cooperation with practitioners cannot be overlooked in this context.

The opinions of practitioners reinforce the ongoing discussion on the role of economic universities in shaping the competences of the graduates as future employees/managers or researchers. The high quality of education at modern universities is an stimulus for and guarantee of growth and economic development of the country. The key issue, however, is the utility of knowledge and competences developed in the course of education, as they are the passport to the labor market. Most of the respondents favor greater instrumentalization of education, pragmatism of competences, which stands in opposition to legislative changes in Poland and the system of financing higher education in recent years. The results of the research indicate that universities should be more focused on the competences of future managers, not academics.

Education programs (majors and specialties) should be designed in a flexible manner, allowing rapid adaptation to new trends, technologies or actual needs of the industry. Therefore, it becomes necessary to systematically monitor trends and innovations in particular industries in order to adapt the content of the curricula to the expectations of employers on an ongoing basis. The introduction of modern technologies and innovative teaching methods – i.e., e-learning platforms, simulations or virtual reality – can significantly enrich the learning process and may be crucial in preparing the employees of the future.

The main internal obstacles associated with organization and people are rigid, long-term, and burdened with bureaucracy operations related to designing curricula, unprepared staff, and lack of motivation among students and staff members themselves. Therefore, it is important to launch plans to overcome these obstacles and promote innovation at universities , including the implementation of modern teaching methods – such as Problem Base Learning or tutoring – which are more effective in imparting skills of design thinking.

The education sector needs to undergo a large-scale transformation process to meet the demands of a turbulent market and reduce the threat of climate change. Nowadays, the role of competences in shaping sustainable development and social cohesion as well as in the circular economy is being emphasized more and more strongly. It is therefore worth considering which competences are most important from the perspective of sustainable development and actions to prevent climate change, and how to teach the design and implementation of social innovations.

Promoting a culture of continuous learning and self-development should become an integral part of educational programs so that future graduates are prepared to keep up with dynamic changes in industries and sectors. What is more, the need for lifelong learning points to the necessity to develop an educational offer for graduates – courses, training (apart from MBA, postgraduate studies) – of varying degrees of intensity and subject matter. The long period between completing university studies and the University of the Third Age still remains to be effectively harnessed.

References

1.Bakhshi, H., Downing, J., Osborne, M., & Schneider, P. (2017). The Future of Skills: Employment in 2030. London: Pearson and Nesta.

2.Dębkowska, K., Glińska, E., Kononiuk, A., Pokojska, J., Poteralska, B., Szydło, J., & Rollnik-Sadowska, E. (2022). Foresight kompetencji przyszłości [Foresight of competences of the future]. Working Paper. No. 1, Warszawa: Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny.

3.Dębkowska, K., Kłosiewicz-Górecka, U., Szymańska, A., Ważniewski, P., & Zybertowicz, K. (2022). Kompetencje pracowników dziś i jutro [Employee competences today and tomorrow]. Warszawa: Polski Instytut Ekonomiczny.

4.Dickerson, A., Rossi, G., Bocock, L., Hilary, J., & Simcock, D. (2023). An analysis of the demand for skills in the labour market in 2035. Working Paper 3. Slough: NFER.

5.Gi Group Holding Polska (2023) Barometr Rynku Pracy 2023 [2023 Labor Market Barometer]. Edycja 17. https://www.gigroupholding.com/polska/insights/barometr-rynku-pracy-2023/

6.Hutmacher, W. (1997). Key Competencies in Europe. European Journal of Education, 32(1), 45–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1503462

7.infuture.institute (2019). Pracownik Przyszłości [The employee of the future]. In collaboration with Samsung. (April 2019).

https://images.samsung.com/is/content/samsung/assets/pl/campaign/brand/pracownik-przyszlosci/pracownik_przyszlosci_2019infuturesamsung.pdf

8.infuture.institute (2021). Przyszłość edukacji: Scenariusze 2046 [The future of education: Scenarios 2046]. In collaboration with Collegium da Vinci. https://www.pcen.gda.pl/files/userfiles/2021-06/5231.pdf

9.Janssens, L., Kuppens, T., & Van Schoubroeck, S. (2021). Competences of the professional of the future in the circular economy: Evidence from the case of Limburg, Belgium. Journal of Cleaner Production, 281, 125365. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2020.125365

10.Krygowska-Nowak, N., Kwinta-Odrzywołek, J., & Datha J. (2022). Branżowy Bilans Kapitału Ludzkiego II: Sektor Komunikacji Marketingowej [Industry Balance of Human Capital II: Marketing Communications Sector]. Warszawa: PARP, Grupa PFR.

https://fers.parp.gov.pl/storage/publications/pdf/Branzowy-Bilans-Kapitau-Ludzkiego-II—sektor-komunikacji-marketingowej_16032022.pdf

11.Kurpiela, S., & Teuteberg, F. (2023). The changing role and competence profiles of strategic oriented jobs in times of product-service systems and business analytics: An analysis of job advertisements. Computers in Industry, 149, 103931. doi: 10.1016/j.compind.2023.103931

12.Lamri, J. (2019). The 21st Century Skills: How soft skills can make the difference in the digital era. The Next Society.

13.Łapińska, J., Sudolska, A. & Zinecker, M. (2022). Raport z badań empirycznych w zakresie kompetencji i zawodów przyszłości [Report on empirical research in the field of competences and professions of the future]. Materiał przygotowany w ramach prac Obserwatorium Kompetencji Przyszłości Fundacji Platforma Przemysłu Przyszłości.

14.ManpowerGroup (2022). Niedobór talentów w Polsce [Talent shortage in Poland].

https://www.manpowergroup.pl/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/INFOGRAFIKA_Niedobor_talentow_wersja_PL.pdf

15.ManpowerGroup. (2023). Industrials World of Work 2024 Outlook, Global Insights. https://workforce-resources.manpowergroup.com/white-papers/global-insights-industrials-report

16.Moczydłowska, J. (2021). Kluczowe kompetencje zmieniających się organizacji – nowe wyzwania na rynku pracy [Key competences for changing organizations – new challenges in the labor market]. Marketing i rynek, 1, 3–10.

17.Moczydłowska, J. M. (2008). Zarządzanie kompetencjami zawodowymi a motywowanie pracowników [Managing professional competences and employee motivation]. Warszawa: Difin.

18.Mościchowska, I., Rogaś-Turek, B. (2015). Badania jako podstawa projektowania user experience [Research as the basis for designing user experience]. Warszawa: PWN.

19.Oleksyn, T. (2006). Zarządzanie kompetencjami, teoria i praktyka [Managing competences, theory and practice]. Kraków: Oficyna Ekonomiczna.

20.Oleksyn, T. (2011). Zarządzanie zasobami ludzkimi w organizacji [Managing human resources in tge organization]. Warszawa: Oficyna Woltrs Kluwer.

21.OLX praca (2021). Prognozy Przyszłości: Know How 2021 [Forecasts of the Future: Know How 2021]. https://zawodowo.olx.pl/raporty/perspektywa-pracownikow-prognozy-przyszlosci-2021.pdf

22.Orczyk, J. (2009). Wokół pojęć kwalifikacji i kompetencji [Regarding the concepts of qualification and competence]. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi, 3–4, 19–32.

23.PwC, Well.hr, & Absolvent Consulting (2022). Młodzi Polacy na rynku pracy. [Young Poles in the labor market]. III edycja badania – maj 2022. https://www.pwc.pl/pl/pdf/mlodzi-polacy-na-rynku-pracy-2022_pl.pptx.pdf

24.Rostkowski, T. (2002). Zarządzanie kompetencjami jako przyszłość ZZL w Polsce [Managing competences as the future of human resources management in Poland]. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi, 6, 65–76.

25.Sajkiewicz, A. (ed.) (2008). Kompetencje menedżerów organizacji uczącej się [The competences of managers of a learning organization]. Warszawa: Difin.

26.Sidor-Rządkowska, M. (2008). Zarządzanie kompetencjami – teoria i praktyka. Zarządzanie zmianami [Managing competences – theory and practice: Managing change]. Biuletyn Polish Open University, 09/2008, www.wsz-pou.edu.pl

27.Spada, I., Chiarello, F., Barandoni, S., Ruggi, G., Martini, A., & Fantoni, G. (2022), Are universities ready to deliver digital skills and competences? A text mining-based case study of marketing courses in Italy, Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 182, 121869. doi: 10.1016/j.techfore.2022.121869

28.Taylor, A., Nelson, J., O’Donnell, S., Davies, E. & Hillary, J. (2022). The Skills Imperative 2035: what does the literature tell us about essential skills most needed for work? Slough: NFER

29.Upskill (2021). Badanie kompetencji na współczesnym rynku pracy. Raport z badań. [The study of competences in the modern labor market: survey report] (2021). https://upskill.net.pl/kompetencje-na-rynku-pracy-raport/#raport-zapis

30.Wagenaar, R. (2014). Competences and learning outcomes: A panacea for understanding the (new) role of Higher Education? Tuning Journal for Higher Education, 1(2), Article 2. doi: 10.18543/tjhe-1(2)-2014pp279-302

31.Wawrzyniak, B. (2001). Zarządzanie kapitałem ludzkim w przedsiębiorstwach [Managing human capital at companies]. Zarządzanie Zasobami Ludzkimi, 3–4, 45–57.

32.Włoch, R., Śledziewska, K. (2023). Kompetencje przyszłości. Jak je kształtować w elastycznym ekosystemie edukacyjnym? [Competences of the future: How to shape them in a flexible education ecosystem?]. Warszawa: DELab UW. https://pfr.pl/dam/jcr:42fb0b02-bae5-4c78-b857-0349ae97f6df/Kompetencje_przyszlosci_7.06_ONLINE.pdf

33.World Economic Forum (2020). The Future of Jobs Report 2020. (October 2020). https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2020.pdf

34.World Economic Forum (2023). Future of Jobs Report 2023. Insight Report. (May 2023).

https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Future_of_Jobs_2023.pdf

Dobrosława Mruk-Tomczak — Employed as an assistant professor at the Poznań University of Economics and Business. She conducts scientific and teaching activities, is a promoter of engineering and master’s theses. Area of interest: marketing communication, creativity, sustainability, brand management, consumer behaviour.

Ewa Jerzyk — Employed as a professor at the Poznań University of Economics and Business. She conducts scientific and teaching activities, is the promoter of master’s and doctoral theses. Research interests: buyer behaviour, marketing communication, design and packaging, neuromarketing.